Training opportunities in Alaska

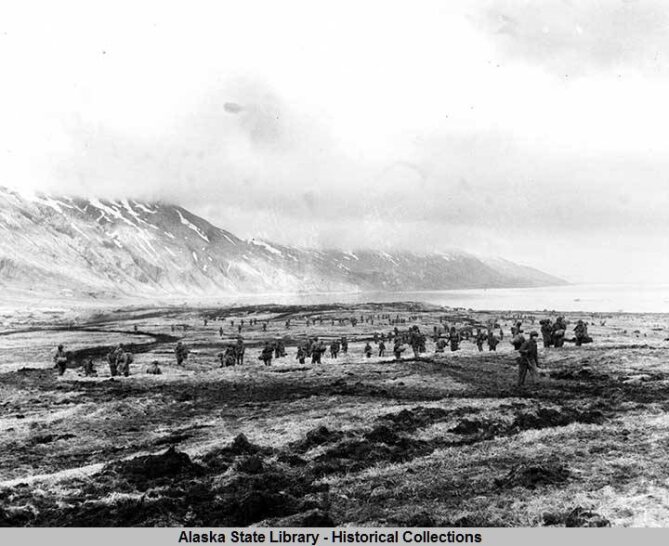

The former Commandant of the Marine Corps (CMC), Gen Berger, released guidance to the Marine Corps with the publication of Training and Education 2030. The publication directs the Marine Corps to discover new venues for training that support every clime and place: “Training must be focused on winning in combat in the most challenging conditions and operating environments. Going forward, we need to explore options and leverage opportunities to train Marines in every clime and place.”1 Alaska was identified as a location requiring further exploration, and the document asked what the Marine Corps’s options are for expanding unit and Service-level training into Alaska to utilize existing multi-domain capable training ranges and venues.2 Sending Marines to Alaska has been discussed many times over the years. The Army acquired a cold weather training facility in Alaska called the Northern Warfare Training Center in Black Rapids, AK. China’s recent airspace breach over the United States started in Alaska with a high-altitude balloon equipped with surveillance antennas and optics. Russia and China conducted combined training near Alaska. First reported by the Wall Street Journal, there were eleven Chinese and Russian ships off the coast of Alaska in August of 2023. The inability of the Navy and Marine Corps to stage, train, and deploy rapidly to Alaska is a strategic gap in the Pacific for the Navy and Marine Corps.

Gen Neller, the 37th CMC, tried to explore Alaska as a future training venue for the Marine Corps. In a December 2017 interview with Military.com, Gen Neller confirmed that the Marine Corps was “exploring ways to add an Alaska location to the currently limited array of options for cold weather training.”3 Gen Neller said, “The one thing Alaska has now is land and space. [The Army has] put a lot of money into their training facilities up there, so we’re looking at how we can take advantage of that … particularly in line with mountain operations and cold weather.” Alaska provides locations to launch and recover an amphibious ready group in the Pacific. Alaska also provides an alternate location to displace in the Pacific away from the island chains in case of a conflict. Alaska supports the focus on the Indo-Pacific and gives robust locations for units operating in the Pacific to train such as the Joint Pacific Alaska Range Complex (JPARC).4

A Better Mountain Warfare Training Center

SgtMaj Daniel E. Mangrum authored an article published by the United States Naval Institute in March 2019 titled, “The Marine Corps Needs a Better Mountain Warfare Training Center.”5 In the article, SgtMaj Mangrum discussed the limitations of the size of the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center (MCMWTC). “Limitations include the Corps’ inability to accommodate MEB-level exercises and constraints on training with mechanized vehicles and combined-arms live fire. The Service has tried to supplement MCMWTC training by sending Marines to other Service installations, such as Camp Ethan Allen in Jericho, VT, or Fort McCoy in WI. These locations do not fully mitigate the limitations, however, thereby denying Marines the large-scale quality training they must have.”6

Alaska is not just for cold weather training. The airspace that Alaska provides can support testing of many weapons systems, with limited aircraft traffic. This kind of airspace offers an opportunity for training with missiles. The Marine Corps is buying medium-range missiles, and Alaska’s airspace provides multiple options for testing and training with these missiles. In 1957, the Army transferred all its cold weather training to Alaska. The schools included the Arctic School, Arctic Indoctrination School, and Cold Weather and Mountain School. Training throughout the 1950s and 1960s was tailored to the individual. Then, in 1963, the Army determined it would be more beneficial for units to participate in cold weather training and redesignated the U.S. Army Northern Warfare Training Center.7 In 2016, Senator Sullivan of Alaska discussed with CMC Gen Neller the future possibilities for Marines to train in Alaska. A Marine himself, Senator Sullivan provided opportunities for Gen Neller to speak to the local Alaskan population and evaluate various locations for future training opportunities.8

Better Training for Norway

Recent experiences from Marines on the rotational force to Trondheim, Norway, have reported that the training work-up for operating in Norway was lacking enough opportunities to fully prepare Marines for the cold weather. A Marine staff non-commissioned officer reported to Military.com that his unit did not have the opportunity to train at the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Facility before deploying to Norway. The Marine’s unit was the first unit to participate in the Norway deployment rotation.9

Dr. Njord Wegge with the Norwegian Defence University College discussed critical security concerns for Norway in 2021 at the Arctic Symposium hosted by the Marine Corps University. The mission statement for the Arctic initiative at the Marine Corps University states, “The Arctic is a region undergoing major changes, and those changes have local, regional, and global impacts. The Arctic has long been a theater of strategic competition. At the same time, the region is marked by decades of cooperation.”10 The mission statement of the Arctic Strategic Initiative states,

The MCU Arctic Strategic Initiative (ASI) was established to create a network of relevant scholars and institutions and facilitate student research in order to generate increased understanding of the nature and challenges of Arctic security for students and faculty at MCU, and to support the Marine Corps and its role in U.S national security.11

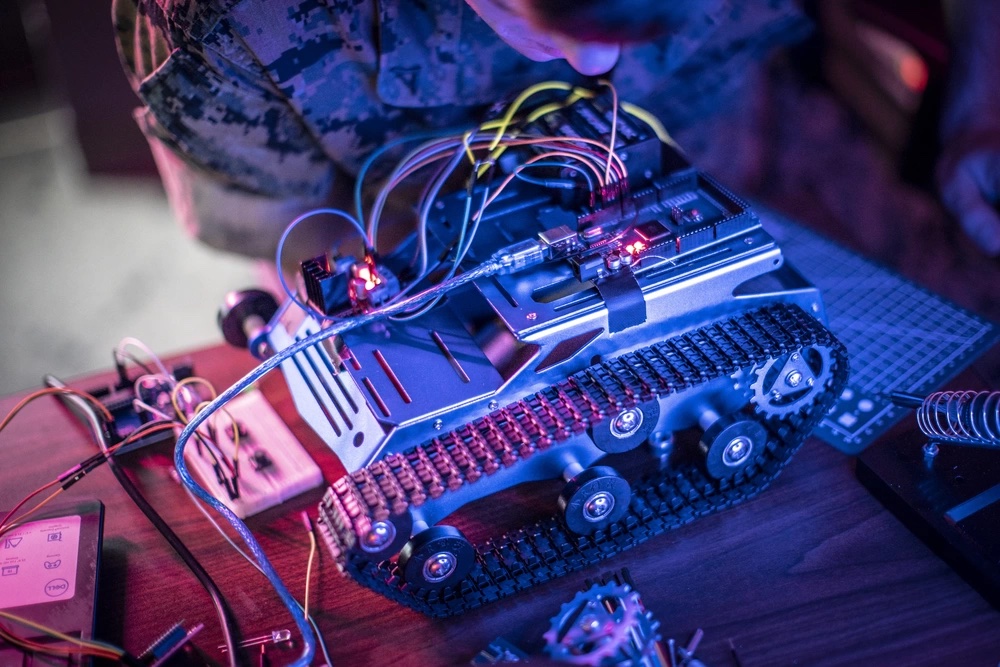

Dr. Wegge listed security concerns for Norway such as Norway’s geographic location to Russia, NATO expansion including Sweden and Finland joining NATO doubling the distance of the NATO border to Russia, the use of F-35 aircraft by Norway, and P-8 integration with submarines around Norway. Challenges of operating in cold weather include but are not limited to, soldiers, sailors, and Marines knowing different methods of staying warm to survive, maintaining batteries and electronics in cold weather, cold weather logistics and resupply, and surviving beyond the grid in cold weather to name a few. Norway serves as the Western flank of Russia and Alaska serves as the Eastern flank.

How do Marines train to be the connecting force for U.S. Army forces coming ashore in the event of a Russian invasion of Norway? The answer is training in Alaska. Marine forces in Norway are just as much a stand-in force as the Marine littoral regiment is in the Pacific. On page one of the Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations, the CMC tasked the force, “Between now and 2023, we will need to test and refine the ideas in this volume to give new formations sufficient guidelines for applying their new capabilities effectively to accomplish their missions.”12 The Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations is intended to be “a foundation for expansion into formal naval doctrine.”13 The development of naval doctrine takes time but units are experimenting across the Marine Corps and one such unit is doing so in Alaska.

What Happened in Alaska?

Recently, an MV-22B squadron conducted a training detachment at Bryant Army Airfield in Anchorage, AK. Alaska was a test of the unit’s ability to operate in extreme cold weather and conduct expeditionary advanced base operations. This exercise was in preparation for conducting proof of concept training for expeditionary advanced base operations planned later in the year for Key West, FL, and the Bahamas.

The unit planned the movement from Marine Corps Air Station Miramar through the West Coast of the CONUS, Canada, and terminated in Anchorage at Bryant Army Airfield. The unit executed through the United States and Canada with little issue but as the unit approached Prince William Sound, AK, and crested over several remaining ridge lines before descending below a cloud level to maintain visual meteorological conditions the unit and flight found itself in a weather phenomenon not found in many areas of the world except the Arctic. The temperatures were below freezing, and the flight was avoiding instrument meteorological conditions to prevent ice from building up on the aircraft. South of Boulder Bay, AK, the micro-climate began to change rapidly. A wall of frozen clouds began to close around the flight of aircraft. The division found itself enclosed in clouds with 13,000 feet of freezing clouds above it. Extreme micro-climates, such as the climate the squadron was flying into, are a phenomenon found only in a few areas in the world. The pilots in the flight were unfamiliar with operating in this type of climate. The exposure to the micro-climate and the actions taken as a result spurred discussions about how to plan for such environmental conditions. Micro-climates found in Alaska provide for greater training and improved tactical proficiency in any clime and place.

The flight safely landed at an unplanned austere runway as the visibility rapidly reduced to less than one-half mile. Landing on the unimproved runway, the flight crews began discussing whether the local villagers would welcome the Marines. The aircraft shut down and the crews started gathering the equipment to secure the aircraft. Stepping out of the aircraft, a local village member met the crew. After a few minutes of talking, one of the senior pilots rode on the back of a quad all-terrain vehicle to the local school building. The local village member unlocked the building and helped with turning the boiler on for hot water. After touring the building, the pilot was back on the all-terrain vehicle heading back towards all the aircraft that had landed on a small dirt strip and parked on the unimproved aircraft ramp. The island had limited cell phone reception and only one service was providing cell phone reception in the area. Those who had cell phone coverage were able to make calls to notify different agencies that we had made an unscheduled landing on a small island south of Anchorage. The size of the footprint was about a platoon’s worth of Marines. The Marines did not have much food on the aircraft and collaborated with the local villagers to help feed the Marines while using the school building. The weather continued to be less than the minimum needed to launch for the next several days. The local village was extremely supportive, brought food, and allowed the Marines to continue staying in the school gym while waiting for the weather to clear.

The division of aircraft was low on fuel. Planning for the follow-on flight included finding the closest location to receive fuel that would support the division of aircraft. The closest fuel location did not have enough fuel in the fuel trucks to support the fuel required for all three aircraft. Pilots on the flight knew several Air Force pilots at the local KC-130 aerial refueling squadron and called to see if they would be able to aerial refuel the flight after launching from the intermediate fuel location to meet the minimum fuel requirements to recover to Bryant Army Airfield. The Air Force launched to support. After taking the remaining fuel at the closest refueling location, the flight departed to rendezvous with the Air Force refueling tanker. Following receiving fuel, the flight continued to Anchorage.

The MV-22 aircraft in the division did not have functioning anti-icing capabilities, which is common in the MV-22 community. H-1 helicopter platforms cannot fly in icing conditions. Similarly, the CH-53 has limited anti-icing capabilities and cannot fly in icing conditions. All constraints that pose challenges when operating in cold environments. Contingency planning becomes crucial and vertical lift becomes a requirement when needing to land as weather changes rapidly. Consistently operating in an environment that requires systems that combat cold weather further incentivizes investment in cold weather capabilities not only for aircraft but for all systems and weapons. It would be easy to focus only on aircraft anti-ice capabilities, but operating in this environment presents multiple challenges to overcome tactically and operationally.

The Northern Edge

To optimize training, the Marine Corps would need to find new locations for restricted live-fire training. “The Joint Pacific Alaska Range Complex (JPARC) is comprised of approximately 65,000 square miles of available airspace, 2,490 square miles of land space with 1.5 million acres of maneuver land, and 42,000 square nautical miles of surface, subsurface, and overlying airspace in the Gulf of Alaska.”14 The JPARC supports joint large-scale exercises such as NORTHERN EDGE. One of the standout evolutions of NORTHERN EDGE is the number of high-end experiments and demonstrations conducted. This in conjunction with virtual training could expand the scope of current Marine Corps training capabilities.

The two after-action reports for NORTHERN EDGE 2021 on the Marine Corps Center for Lessons Learned SharePoint came from Marine Air Control Group 38 and Marine Aerial Refueler Squadron (VMGR) 152. VMGR-152 discussed the requirements for coordination ahead of NORTHERN EDGE 2021, requirements that would not be as necessary with a permanent Marine Corps training facility. “The detachment did not reach out to Marine Forces Pacific (MARFORPAC) about planning for NORTHERN EDGE until six months prior to the exercise.”

At this point, the initial planning conference had been conducted and the MARFORPAC lead planner decided to bed down the KC-130s in Cold Bay, AK. Concerns over the lack of maintenance support at Cold Bay were brought up to the MARFORPAC planner and a request to move the detachment to either Eielson or JBER (Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson) was made in December 2020. The detachment did not get confirmation that their bed down would be at Eielson AFB until March 2021. It was discovered that none of the logistics support requests submitted to MARFORPAC over the preceding three months had been forwarded to the Air Force. This caused the detachment planner and officer in charge (OIC) to conduct all the logistics maintenance support requests within 60 days of arrival to Eielson AFB. VMGR-152 highlighted that, “the JPARC range complex is heavily used for training (by the Air Force and Army) and requires significant lead time to ensure that desired range space, emitters, and (smoky surface to air simulators) are scheduled and secured.”15 Marine Air Control Group-38 covered an extensive list of planning constraints and execution milestones in their after-action report.16A permanent presence of Marines in Alaska would provide improved planning, better coordination, and improved proficiency with cold weather logistics, communications, operational planning, and tactical execution for units.

The Marine Corps needs more repetitions in Alaska and the Arctic, and planning evolutions continue to experience friction due to shortfalls in knowledge of planning requirements for cold-weather environments. Is it time for the Navy and Marine Corps to invest in Alaska to fill this strategic gap?

Notes

1. Headquarters Marine Corps, Training and Education 2030, (Washington, DC: 2023).

2. Ibid.

3. Hope Hodge Seck, “Marines May Go to Alaska for Cold Weather Training,” Military.com, February 18, 2023, https://www.military.com/daily-news/2018/02/18/marines-may-go-alaska-cold-weather-training.html.

4. United States Army, “Joint Pacific Alaska Range Complex Reference Card,” JPARC, n.d., https://www.jber.jb.mil/Portals/144/units/JPARC/PDF/JPARC-Fact-Sheet.pdf.

5. Daniel E. Mangrum, “The Marine Corps Needs a Better Mountain Warfare Training Center,” Proceedings, March 2019, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2019/march/marine-corps-needs-better-mountain-warfare-training-center.

6. Ibid.

7. United States Army, “Northern Warfare Training Center,” Army.mil, November 13, 2018, https://www.army.mil/article/170432/northern_warfare_training_center.

8. Zachary Hughes, “Could the Marine Corps be Coming to Alaska?,” Alaska Public Media, July 25, 2016, https://www.ktoo.org/2016/07/25/marine-corps-coming-alaska.

9. “Marines May Go to Alaska for Cold

Weather Training.”

10. Marine Corps University, “Arctic Strategic

Initiative,” Marines.mil, n.d., https://www.usmcu.edu/Research/Arctic-Strategic-Initative.

11. Ibid.

12. Headquarters Marine Corps, Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advance Base Operations, (Washington, DC: 2019).

13. Ibid.

14. “Joint Pacific Alaska Range Complex Reference Card.”

15. Marine Corps Center for Lessons Learned, Marine Aerial Refueler Transport Squadron 152 After Action Report for Northern Edge 2021, (Quantico: 2021).

16. Marine Corps Center for Lessons Learned, Marine Air Control Group 38 After Action Report for Northern Edge 2021, (Quantico: 2021)