Why the Service is incapable of repeating June 1950

When the Korea People’s Army stormed across the 38th parallel on 25 June 1950, the Republic of Korea Army and the U.S. Far East Command were caught off guard. The Marine Corps’ rapid response in July 1950 and the 15 September 1950 landing at Inchon are the pinnacle of Marine Corps history and lore. However, the tactical and operational victories in late 1950 were the ends of the lesser-known but critically important ways and means of Service-wide mobilization. Today, the Service is consumed by a focus on tactical-level technologies, experimentation, and endless pursuit of operations, activities, and investments while being hamstrung by years-long acquisitions, delays in production, and structure design based on how many things purchased and not the enemy. If the Marine Corps does not plan for total mobilization, the next large-scale, unexpected enemy attack will result in the Corps weathering the initial storm, then looking over its shoulder and finding nothing there to carry on the fight.

Tactical technologies and tactical-level victories are for naught if not woven into operational objectives to achieve strategic ends. The fundamental concept of massing combat power more quickly than the enemy and applying that combat power at a time and place of your choosing is how conflicts are won. When the size of the force in the conflict is insufficient, the force that can rapidly flow and sustain the most combat power seizes the advantage. Throughout the history of warfare, this is done via mobilization, defined today as “the process by which the Armed Forces of the United States, or part of them, are brought to a state of readiness for war or other national emergency.”1 Often mistaken as the simple act of placing a reserve component (RC) Marine into an active-duty status, mobilization is in fact a whole-of-Service task tied to strategic and operational concepts and codified in the requirements of Title 10, U.S.C. §10208: Annual Mobilization Exercise.2 Unfortunately, the Marine Corps has lulled itself into the mistaken belief it is capable of mobilization because it has achieved battlefield successes over the last 85 years of modern conflict.

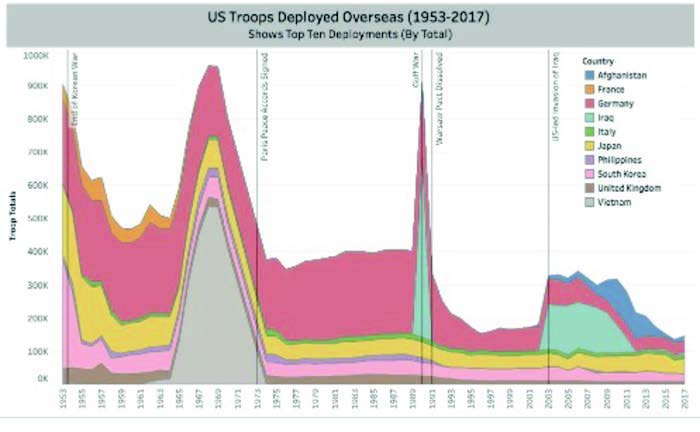

The reality of the last 85 years is that the United States has delayed entry into every major conflict except one, the Korean War. World War II began in September 1939, with the United States not officially entering until December 1941. The U.S. involvement in Vietnam began in 1950 with advisors, the number expanding in 1962, with major combat actions not occurring until 1965. DESERT STORMsucceeded thanks to DESERT SHIELD, a five-month buildup of combat power that the enemy was kind enough to sit and observe. Finally, Operation IRAQI FREEDOM (OIF), authorized on 16 October 2002 via Congressional Joint Resolution, did not see combat operations commence until 20 March 2003.3 Each of these conflicts provided the Marine Corps with the benefit of time. Time to plan, build, and position forces to assure the successful commencement of combat operations. When the Marine Corps looks around the globe today, time is not a benefit. The United States’ competitors are positioned to strike quickly and with significant combat power. It is for this reason that the initial stages of the Korean War must be the priority case study if the Marine Corps wishes to wake from its mobilization slumber.

An assessment of June 1950 and today reveals many similarities throughout the Corps. The 1946–1950 drawdown saw active component (AC) end strength decrease from 155,592 to 74,279 (52 percent decrease).4 Current AC end strength has also decreased from 183,417 in 2015 to 172,300 (6 percent decrease) in 2024.5 The Marine Corps Organized Reserve (Ground and Air) of 1950 totaled 39,869 personnel, with the 2024 Selected Marine Corps Reserve (SMCR) end strength equaling 32,000 personnel.6 In both eras, military technologies entered a new age of innovation. With Far East Command, the United States positioned itself forward under a unified combatant command to counter Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union and Mao Zedong’s China. Today, unified commands around the globe campaign forward with modern technologies to deter competitor aggression, with Marines present in all theaters. Unfortunately, these surface-level similarities mask massive underlying contrasts and a glaring critical vulnerability for the Service.

Two critical factors are missing from today’s Marine Corps that existed in 1950. First, in 1950, there was a base mobilization plan.7 Today, the last signed DOD-level mobilization plan is dated May 1988, and the Service has no single-source plan, policy, or Marine Corps Order addressing how it will pick up the entire force, take it to war, while simultaneously preparing for protracted conflict. Second, as early as November 1947, studies of Reserve availability provided data for use in force flow planning in the immediate days and weeks following the surprise assault by the Korea People’s Army on 25 June 1950.8 When the commanding generals of Marine Barracks, Camp Pendleton, and Camp Lejeune were given the warning order to expect 21,000 and 5,800 reserve Marines, respectively, the extensive surveys of facilities and supplies necessary were conducted. More importantly, the arrival of RC forces was integrated with the arrival of 3,600 AC Marines from 105 varying posts and stations and the movement of 6,800 Marines of 2d MarDiv from Camp Lejeune to Camp Pendleton, who arrived within a 96-hour window.

The scope, scale, and timeline of execution for this effort are staggering and were made possible only because the Service deliberately planned in time of peace for mobilization in time of war. Following the 26 June 1950 authorization for the employment of military forces in Korea by the President of the United States (POTUS), the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade (Reinforced) set sail from Camp Pendleton on 14 July. On 20 July, 22 RC units were ordered to active duty, with the entire Organized Reserve (138 units in total) ordered to active duty by 4 August. The first Organized Reserve (Ground) Marines arrived at Camp Pendleton on 31 July and reported for active duty through 11 September at a rate of 702 per day, seven days per week. The first of 1,392 Organized Reserve (Aviation) Marines arrived at Marine Corps Air Station El Toro on 1 August alongside the AC Marines of MAG-15 and VMG-212 from Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point to build 1st MAW to wartime strength. When the 15 September landing at Inchon began, seventeen percent of the force was from the RC.9

When viewed in relation to the two most recent large-scale conflicts, DESERT SHIELD/DESERT STORMand OIF, the gravity of the 1950 mobilization is evident. From 28 October 1990 to 13 January 1991, during Operation DESERT SHIELD, the SMCR activated 22,703 personnel.10 This process took 25 days (48 percent) longer than the actions of 1950 and included 9,411 fewer (-29 percent) personnel. From January to May 2003, in support of OIF, the RC activated approximately 17,000 personnel on top of the roughly 3,000 already activated between November 2001 and December 2002. This four-month spike was the largest during the entire conflict, took 98 days (185 percent) longer than the actions of 1950, and included roughly 15,800 fewer (-48 percent) personnel.11 In both conflicts, fewer RC personnel were activated over longer periods, with the enemy static in both cases. This makes clear that the Marine Corps should not evaluate its ability to mobilize against an actively advancing peer threat using either of these modern conflicts as a case study.

Were the Marine Corps to begin actively planning for the actions accomplished during the early days of the Korean War, detailed above, it would at best only achieve operational relevance within the Joint Force and the eyes of our Nation’s competitors. In the era of competition and campaigns to deter, strategic relevance for the Service is not made through quickly aggregating initial response forces but by demonstrating the ability to rapidly aggregate, grow, and sustain the force in protracted conflict against a peer.

To understand the strategic relevance the Service created during the Korean War, an additional layer of analysis beyond the process for aggregating forces for the 1st MarDiv and 1st MAW must be studied. As the Marines at Camp Pendleton and El Toro fulfilled unit requirements and built the foundational cadre necessary for additional unit creation, such as the 7th Mar, Headquarters Marine Corps actively planned and executed policy and long-term force flow decisions. United States policymakers moved quickly following the POTUS decision to intervene militarily. On 30 June, Congress approved the Selective Service Extension Act of 1950, nullifying the guarantee that RC personnel would not be called to active duty except in time of war or national emergency.12 On 19 July, the day after the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade (Rein) set sail for Korea, POTUS authorized the Secretary of Defense to increase the size of AC end strength and call up RC personnel, and the Commandant, with the Secretary of the Navy’s approval, halted the discharge of RC personnel.13 The same day, the Division of Plans and Policies drafted a delay policy based on the mobilization force flow plan. One day later, those instructions were distributed across the Service. The Marine Corps’ strategic relevance had begun.

The Marine Corps’ strategic planning accelerated even as the operational planning hit the pinnacle of its fervor. As AC and RC forces flowed west within the continental United States (CONUS) from 20 July to 4 August 1950, policy maker decisions continued to unfold. The 25th of July saw the chief of naval operations authorize a 50 percent reduction in Marine security forces within CONUS. On 27 July, Congress passed Public Law 624, giving POTUS the authority to extend enlistments.14 The next day, the CMC directed the extension of one year for all enlistments set to expire before 9 July 1951, and Marine Corps RC members were prevented from joining another reserve or regular component of a sister Service. At the beginning of August, Headquarters Marine Corps established the Board to Consider Requests for Delay, which began meeting daily. These decisions not only supported the sourcing of combat forces over time but also set conditions for a critical next step.

This step came in mid-August 1950 with the decision to begin activation of the Volunteer Reserve and planning for that force to arrive at CONUS screening stations on the heels of the Organized Reserve (Ground and Air). This phase shifted the Marine Corps from operational to strategic-level importance. The Volunteer Reserve, which in today’s Marine Corps is best described as a combination of the Individual Ready Reserve and the Individual Mobilization Augmentee program, held 89,920 Marines on 30 June 1950.15 On 15 August 1950, one day after the first attack transports carrying 1st MarDiv set sail from California and two days before the 7th Mar activated, all E-5 and below Marines of the Volunteer Reserve were ordered to active duty. Only two weeks prior, the Joint Chiefs of Staff had ordered the Marine Corps to bring 2d MarDiv to wartime strength and increase the number of flying squadrons. With Camp Lejeune already depleted of forces now sailing with 1st MarDiv, long-range building of forces was dependent on the RC.

Mobilization history was made on 15 September 1950, with the landing at Inchon, but the true benefits of mobilization planning would not be realized until the night of 27 November, when the Chinese People’s Volunteer Force attacked at the Chosin Reservoir. On 25 October, a month before the attack, the Commandant directed all Volunteer Reservists to be ordered to active duty with a 30-day delay. By 8 November, the Service, believing it was in a “short war,” adjusted those plans to include a four-month delay.16 Following the 6–11 December Chosin breakout, it was clear the short war was now a long war. Although the four-month delay policy was suspended on 6 January 1951, because of enemy action, the previously made mobilization decisions had already enabled a continuous flow of Marine Corps forces as the war took a new direction.

Confident in its ability to continue combat operations despite an ongoing Chinese People’s Volunteer Force, which would last until April 1951, on 10 January, the Service approved RC enlisted members enrolled in officer candidate programs to continue, enabling long-term officer procurement. On 10 February, RC members with contracts expiring between 28 February and 9 July were not ordered to active duty. By March, the preliminary plan to release reservists from active duty was drafted, and by June, the plan was put into action. A largely RC effort now transitioned to a long-term Selective Service solution thanks to robust and detailed mobilization planning.

It must be acknowledged that the Marine Corps of 1950 was not like the Marine Corps of 2025. The AC in June 1950 consisted of 74,279 personnel—just 43 percent of today’s authorized end strength of 172,300.17 Active component units in June 1950 were reduced in personnel numbers to a peacetime structure, with billets intentionally unfilled unless brought to wartime standing. A Marine division in peacetime had 45 percent fewer Marines and 41 percent fewer sailors than the wartime totals of 20,131 and 997, respectively. In June 1950, actual AC staffing meant that 1st and 2nd MarDiv combined could not produce a full wartime division.18 Today, there is no differentiation between peace and wartime structure. Marine Corps units, both AC and RC, are held to readiness reporting requirements in the areas of personnel, equipment supply and condition, and training.19 Within today’s RC, the SMCR, as previously mentioned, is 80 percent of the 1950 Organized Reserve (Ground and Air). The Individual Ready Reserve and Individual Mobilization Augmentee combination of approximately 57,000 personnel is 63 percent of the 89,920 Volunteer Reserve of 1950. By the numbers, the Marine Corps has reduced the size of its 1950 RC by approximately 40,000 (129,000 to 89,000) while increasing the 1950 AC by approximately 98,000 personnel. The surface-level, and incorrect, conclusion is that this shift of RC to AC manpower over the last 75 years has created a total force more capable of meeting mobilization requirements.

Analysis beyond the simple numerical increase of AC personnel reveals that today’s Marine Corps has less relative combat power than the Marine Corps of 1950. This is evident when comparing the two most powerful arms of the MAGTF, the infantry battalions and fighter squadrons. In 1950, the AC had three infantry regiments (2d, 5th, and 6th) with a wartime structure of three battalions each. The RC had 21 infantry battalions with an additional 16 individual rifle companies.20 Assuming three rifle companies form a battalion, the combined AC and RC infantry battalion strength of the 1950 Marine Corps was approximately 35. Today, the combined AC and RC infantry battalion strength is 28, including 3d Littoral Combat Team, or 80 percent of 1950. Fighter squadrons in 1950 for the AC totaled 15, with another 30 in the RC for a combined total of 45. Today, the combined AC and RC fighter squadron strength is 19, or 42 percent of 1950. In terms of the Corps’ most recognized form of combat power throughout history, the modern Marine Corps is lacking in both when compared to the Corps of 1950.

In addition to the 20 percent fewer infantry and 58 percent fewer fixed-wing strike aircraft than in 1950, the modern Marine Corps risks being out of position when the next conflict begins. Relentlessly pushed outside CONUS in campaigns to deter, repositioning the 45,000+ personnel of I MEF or the 22,000+ personnel of III MEF would be significantly more challenging than the movement of only 800 outside CONUS personnel to complete the 7th Mar upon their arrival in-theater in September 1950. If the enemy chooses to begin the next rapidly evolving peer conflict outside the location where the Marine Corps has hedged its bets, the mobilization planning of 1950 will be dwarfed in complexity by the next iteration as the Service attempts to mobilize and aggregate forces from around the globe.

The modern Marine Corps has further undermined its ability to mobilize by neglecting equipment modernization in the RC. Readiness of the AC and RC in 1950 was instrumental in the successful mobilization of forces. Although at peacetime strength, the material readiness of 1st MarDiv and 1st MAW was 98.3 percent and 95.6 percent, respectively.21 The delta for wartime tables of equipment was made up by using the 30-day replenishment stock, air and ground units arriving from Camp Lejeune bringing their equipment, a long-range policy for resupply with the Army and Air Force, and 30-day incremental resupply by Marine or Navy agencies for Marine-specific equipment.22 Most importantly, during the inter-war period of World War II and Korea, the RC “operated up-to-date equipment”23 when training. When the mobilization plan went into execution, the AC and RC were on a level playing field, enabling seamless integration into forces deploying forward and assignment of AC and RC personnel within CONUS to serve as cadre for newly activated units and training cadre for volunteers and those Marines requiring accession training. Today, the RC is consistently last, if included at all, in the fielding of modern equipment and trains with a training allowance, a lesser amount than a full table of equipment. If the RC were called upon again as it was in 1950, it would not arrive trained on modern equipment, and it would bring insufficient numbers of legacy equipment.

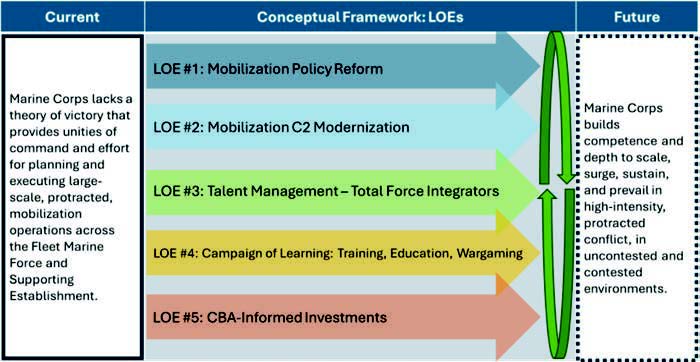

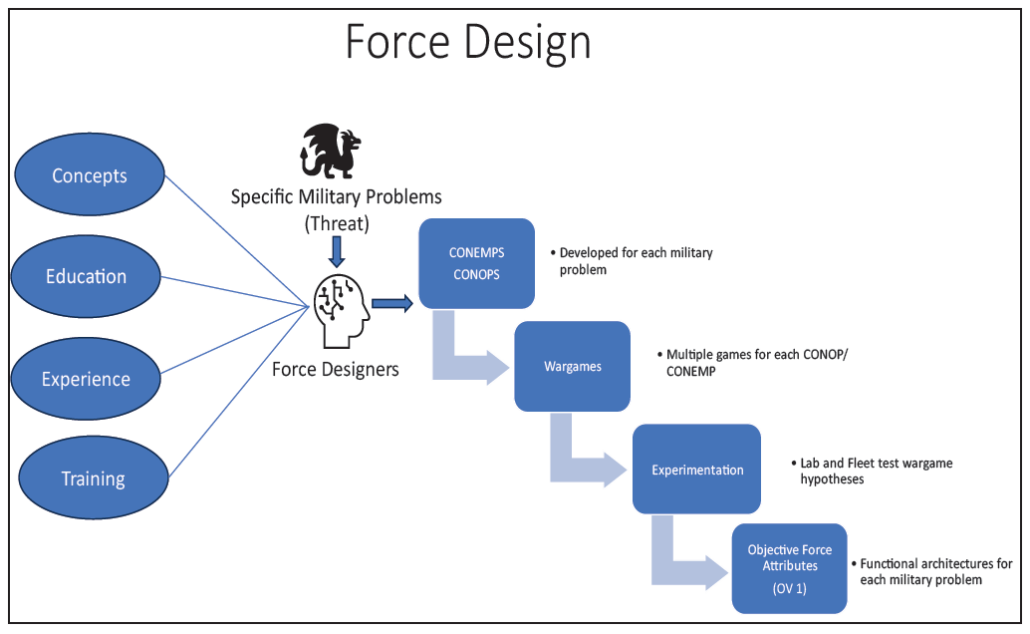

If the Marine Corps wants to be relevant at the operational and strategic levels of war in the next peer conflict, it must learn and apply the lessons from June 1950 and establish a base mobilization plan and a properly equipped RC. Planning must include how the Service will execute seamless transition between initial response, RC call-up, end strength increase, arrival of volunteers and/or Selective Service System inductees, and rotation considerations. More importantly, a total force mobilization plan must identify key policy decisions and be rehearsed and exercised under Title 10 requirements. This sends a message to strategic competitors that the Marine Corps is not a tactical-level force with a handful of exquisite weapons, but a strategic-level consideration capable of rapid expansion and prepared to seamlessly flow combat power in a well-orchestrated symphony of destruction.

“Without the reserves, the Inchon landing on September 15 [1950] would have been impossible.”

—MajGen Oliver P. Smith,

Commanding General,

1st Marine Division

>LtCol Toulotte is currently assigned as the Inspector-Instructor for 3d Civil Affairs Group. He is an Infantry Officer who has served in both the Selected Marine Corps Reserve (SMCR) and Active Reserve (AR). In his previous assignment as an Operational Planner to Marine Forces Reserve (MARFORRES), he represented the command in both Service and Joint-level mobilization planning efforts.

Notes

1. Department of Defense, Department of Defense (DoD) Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Washington, DC: 2025).

2. Title 10, §10208: Annual Mobilization

Exercise.

3. H.J.Res.114-Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002, 107th Congress (2002).

4. Headquarters Marine Corps, Mobilization of the Marine Corps Reserve in the Korean Conflict 1950–1951 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1967).

5. Nicholas Munves, “FY2025 NDAA: Active Component End-Strength 21 Oct 2024,” Congress.gov, October 21, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IN12449.

6. Nicholas Munves, “FY2025 NDAA: Reserve Component End-Strength 21 Oct 2024,” Congress.gov, October 21, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IN12448.

7. Mobilization of the Marine Corps Reserve in the Korean Conflict 1950–1951.

8. Ibid.

9. Staff, “History: Marine Forces Korea,” Marines.mil, n.d., https://www.marfork.marines.mil/About/History.

10. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Desert Shield/Desert Storm Employment of Reserve Component: Extracts of Lessons Learned (Fort Eustis: Joint Deployment Training Ctr, 1998).

11. Department of Defense, RC Support to GFM Operational Requirements (Washington, DC: January 2010).

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid; and “FY2025 NDAA: Active Component End-Strength.”

18. Ibid.

19. Headquarters Marine Corps, MCO 3000.13B, (Washington, DC: July 2020).

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Lynn Montross and Nicholas Canzona, U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, Volume II (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, Headquarters Marine Corps, 1955).

23. Ibid.