Balancing crisis response and modernization

The Deputy Commandant for Aviation’s (DC A) 2025 Aviation Plan (AVPLAN) was signed and released this past January. The AVPLAN intends to communicate to the FMFs, our industry partners, and Congress, the DC A’s priorities and direction over the next five years, guided by the 39th Commandant’s Planning Guidance and his priorities. Notably, the Commandant’s priority of “Balancing Crisis Response and Modernization” lies at the forefront of this AVPLAN and has guided Marine Aviation’s strategy to maintain a ready and lethal force.

Project EAGLE outlines DC A’s strategy to modernize Marine Aviation across multiple future year defense programs. The Project EAGLE initiative focuses on expanding interoperability with the Joint Force and allies, evolving the Marine Air Command and Control Systems, and incorporating new functional concepts such as Distributed Aviation Operations and Decision-Centric Aviation Operations. We will transform Marine Aviation to meet future operational needs by focusing on unmanned platforms, logistics, digital interoperability, and manned-unmanned teaming, ensuring a competitive advantage in future conflicts and supporting both the naval and Joint Forces across all domains.

To accomplish this, Marine Aviation must be ready. Therefore, operational readiness is the DC A’s number one priority. The challenge is to maintain a high level of readiness and remain lethal to respond to crises while also modernizing aviation capabilities. As we maintain this balance between crisis response and modernization, the DC A will ensure Marine Aviation remains lethal, naval at its core, and ready to respond to crises with the warfighting edge necessary to support our Marines, sailors, and the Joint Force.

Marine Aviation will also pursue a demand-based sustainment strategy, improving fleet readiness through better collaboration and efficient resource delivery. Efforts are being made to reduce variability in aircraft readiness through optimized maintenance, tooling, and logistics. Sustainment solutions will focus on three lines of effort: improving fleet readiness, enhancing sustainment for distributed aviation operations, and reducing equipment variability. This includes modernizing aviation supply packages, enhancing logistics information systems, and developing a replacement for aging aviation logistics vessels. This comprehensive approach ensures Marine Aviation can effectively support the MAGTF throughout the full range of military operations.

Qualified Marines also remain the key to our ability to meet operational requirements. While each type, model, and series of aircraft is in a different phase of lifecycle and inventory management, Marine Aviation will remain focused on managing aircrew and maintainer inventories by building properly-sized populations in grade, qualifications, and experience levels. To realize these goals, Marine Aviation will first reestablish a manpower management branch within Marine Aviation.

Marine Aviation Capabilities and Commodities

Marine Aviation aims to maintain a powerful and responsive air combat element for the MAGTF. This includes transitioning to an all-5th generation tactical air (TACAIR) fleet and modernizing the air combat element to be ready for combat today and tomorrow. The DC A’s intent is to maintain the current F-35 and CH-53K transition plans while also ensuring each community employs the most ready, safe, and lethal aircraft.

First, the F-35 B/C provides advanced sensors, air-to-air missiles, and air-to-surface strike weapons, which are crucial for the MAGTF and Joint Force mission globally. By 2025, the Marine Corps will have received 183 F-35B and 52 F-35C aircraft. The F-35 program aims to support 12 F-35B squadrons and 8 F-35C squadrons, with a total of 420 F-35 aircraft. Fleet squadrons will be increased to 12 primary aircraft authorization by fiscal year (FY) 2030. The F-35B/C modernization includes Technical Refresh-3 upgrades, APG-85 radar upgrades, advanced countermeasures, and electronic warfare improvements. The program is focused on Block 4 capabilities, weapons integration, and site activations.

The F/A-18 Hornet provides vital maritime strike and air interdiction capabilities, with ongoing modernization ensuring its effectiveness in the Marine Corps’ TACAIR Transition Plan and global operations. The Marine Corps operates 161 F/A-18 aircraft, transitioning squadrons annually until FY29, with aircrew training now conducted by the Fleet Replacement Detachment at VMFA-323. The Hornet’s increased lethality with the AN/APG-79(v)4 radar and AESA technology, alongside upgrades in electronic warfare, extended-range weapons, and communications. Funding priorities focus on integrating advanced weapons, improving beyond-line-of-sight capabilities, enhancing electronic warfare systems, and supporting precision approach capabilities.

The AV-8B Harrier provides critical Vertical/Short Take-Off and Landing capabilities for the MAGTF, offering precision strike, escort, and rapid deployment for MEUs with advanced targeting and missile systems. The Marine Corps operates 39 AV-8B aircraft across two VMAs, with plans for VMA-231 and VMA-223 to transition to F-35B. The AV-8B will continue supporting training and combat operations for forward air controllers and joint tactical air controllers, providing flexible deterrence and combat capabilities to combatant commanders. Funding will focus on T402 engine readiness, full LINK-16 integration, fleet replacement squadron support, and weapons upgrades.

The KC-130J is a vital enabler for MAGTF success, providing global mobility, logistical support, and aerial refueling across multiple regions with increased capacity in the Indo-Pacific. Four Marine aerial refueler transport squadrons operate 75 KC-130J aircraft with the full transition expected by 2027, which includes a program of record of 95 aircraft. The aerial refueler transport team is working to integrate more effectively with the MAGTF and joint forces by enhancing capabilities like realtime data transmission and adjusting training devices to support expanded training needs. Funding will focus on hardware and software upgrades, integrating MAGTF Agile Network Gateway Link, procuring infrared countermeasure kits, and expanding backup aircraft inventory to maintain operational capacity.

The MV-22 Osprey provides critical medium-lift assault support with unmatched speed, range, and payload, ensuring rapid response for global crisis and humanitarian missions. The Marine Corps has a program of record for 360 MV-22Bs, organized across 16 active squadrons, 2 reserve squadrons, and several test and executive transport detachments, with VMM-264 reactivating in FY26. Ongoing efforts focus on improving configuration management, increasing fleet sustainability, modernizing flight control systems for degraded visual environments, and enhancing interoperability with the MAGTF Agile Network. Funding focuses on safety instrumentation for predictive maintenance, technology replacements to mitigate obsolescence, improved nacelle reliability, and new flight control systems to increase aircraft capability and safety.

The CH-53K King Stallion offers three times the range and payload capacity of the CH-53E Super Stallion. It can transport heavy equipment, troops, and supplies over long distances, ensuring forces remain agile and supported. Operating from both land and sea bases, including austere sites and amphibious shipping, it provides essential flexibility to the MAGTF. The Marine Corps plans to procure 200 CH-53Ks, equipping six active squadrons, one reserve squadron, and various test and fleet replacement detachments, with the full transition expected to be completed by FY32. Key efforts for the CH-53K include focusing on aircraft inventory, sustainment, and capability, with the first MEU detachment expected to deploy by FY27. Funding priorities for the CH-53E include sustainment, safety, and interoperability upgrades, while the CH-53K focuses on supply chain capacity, testing, sustainment, and warfighting capability expansion.

The H-1s are essential to the MAGTF, providing multi-role attack and utility capabilities that enhance lethal and non-lethal options, bridging gaps in low-altitude attack and strike operations. The H-1 Program consists of 349 aircraft, with a total active inventory of 301 aircraft across five squadrons and a planned increase to 314 by FY31. The H-1 modernization plan focuses on improving digital interoperability, survivability, lethality, and electrical power capacity, ensuring the fleet remains versatile and capable of future conflicts. The program’s key funding priorities include digital interoperability, power upgrades, survivability, sensor optimization, and aircrew systems enhancements.

The Marine Unmanned Expeditionary Medium Altitude Long Endurance unmanned aerial systems provide critical capabilities such as airborne early warning, maritime domain awareness, and electronic warfare support. The Marine Corps currently operates 10 MQ-9A Block 5-20 aircraft and plans to field a total of 20 Block 5-25 aircraft with ongoing efforts to establish additional unmanned aircraft squadrons. The MQ-9A program focuses on sustaining operations through contract logistics support and the activation of Unmanned Aerial System Maintenance Squadron 1 (UASMS-1) by FY26 to manage maintenance and sustainment for MQ-9A Reapers. Key funding priorities include Marine Unmanned Expeditionary Medium Altitude Long Endurance unmanned aerial systems procurement, capability spirals, UASMS-1 establishment, and improvements in lethality, survivability, and expeditionary deployability.

The F-5 N/F provides essential adversary training for TACAIR, assault support, groundbased air defenses, and Marine air control squadrons, enhancing combat readiness for Marine aviation and ground units. The Marine Corps currently operates F-5s assigned to Marine Fighter/Attack Training Squadron 401 at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma and Marine Fighter/Attack Training Squadron 402 at Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort, with plans to acquire eleven more aircraft over the next four years to meet growing adversary training requirements. The F-5 fleet is undergoing upgrades, including glass cockpits and Red Net integration, while exploring new solutions like LVC capability and commercial air services to address adversary training gaps.

Marine Corps Operations Support Airwing provides critical air transport for high-priority passengers and cargo, ensuring timely logistical support for forward-deployed MAGTFs. The Marine Corps Reserve Operations Support Airwing squadrons, including Marine Transport Squadron 1, Marine Transport Squadron Belle Chasse, and Marine Transport Squadron Andrews, support active-duty Operations Support Airwing operations and lead the management of UC-12W, UC-35D, and C-40A aircraft. The top priority is the recapitalization of non-deployable UC-12F/M and UC-35D aircraft, with plans to procure additional UC-12W aircraft to meet the program of record. The funding priorities include procuring nine UC-12W aircraft and modernizing UC-12W with digital interoperability capabilities.

The HMX-1’s mission includes worldwide transportation for the President and key officials, supporting high-level travel and operational test evaluations for presidential lift aircraft. The HMX-1 began transitioning to the VH-92A in 2022, with the Marine Corps declaring its initial operational capability in December 2021 and having since integrated the aircraft into operational missions. With a total of 23 aircraft in the program of record, the VH-92A is set to fully replace the VH-3D and the VH-60N, with ongoing improvements in performance for high/hot environments and expanded communication capabilities.

Marine Aviation is advancing new weapon systems to address evolving threats, integrating capabilities that enhance fighter and attack aircraft for global operations. The focus is on munitions with greater range, speed, and lethality to dominate both air and surface domains. Recent efforts have concentrated on integrating net-enabled weapons into the F-35B/C and improving long-range maritime strike capabilities. Key developments include the Advanced Anti-Radiation Guided Missile-Extended Range entry into low-rate production, safe separation testing for the GBU-53 SDB II, and the addition of the Long-Range and Maritime Strike to the F-35B/C roadmap.

The AGM-158C Long-Range and Maritime Strike is a long-range, precision-guided anti-ship missile designed for semi-autonomous engagement of maritime targets. Its integration with the F-35B/C enhances Marine Aviation’s strategic maritime capabilities.

The Joint Air-to-Ground Missile program is undergoing operational testing on the AH-1Z. Its dual-mode seeker and multi-purpose warhead provide enhanced strike precision while its countermeasure resistance and fire-and-forget capability improve survivability in diverse conditions.

Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System II, integrated across platforms carrying 2.75” rockets, offers significant improvements over unguided rockets, particularly in precision targeting. The Single Software Variant, fielded in FY22, provides increased range and accuracy, enabling common use across fixed and rotary-wing platforms.

The AIM-9X Block II Sidewinder introduces lock-on-after-launch with data-link for 360-degree engagements, and its Block II+ variant will support F-35B/C in FY19. The AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile, with its ability to engage multiple targets simultaneously, is further enhanced by the AIM-120D variant, featuring GPS, improved data link, software, range, and speed.

The evolving electromagnetic environment necessitates advanced electromagnetic spectrum operations capabilities to ensure the MAGTF maintains superiority and can effectively deny the enemy’s electromagnetic spectrum use while protecting its own. Marine Aviation is integrating the electronic warfare family of systems with a focus on platforms like the UH-1Y, MV-22, and KC-130 while developing capabilities for unmanned systems through collaboration with the Marine Corps Spectrum Integration Lab.

The goal of MAGTF Digital Interoperability/MAGTF Agile Network Gateway Link (DI/MANGL) is to deliver timely, efficient, and secure information across diverse systems to enhance situational awareness, accelerate the kill chain, and improve survivability. The DI/MANGL program is modernizing to align with Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control standards, advanced tactical data links, and zero-trust architecture, with funding efforts planned for FY26. The DI/MANGL integrates sensors, processors, interfaces, and radios to improve interoperability and situational awareness across the MAGTF, joint, and coalition forces while ongoing efforts expand tactical relevance and mobility.

The goal of aircraft survivability equipment (ASE) is to equip all aircraft with advanced systems that enhance survivability and situational awareness to detect, identify, and defeat anti-aircraft threats while integrating into the MAGTF C2 ecosystem. Current ASE systems include various missile warning systems, radar warning receivers, and countermeasure systems, all aimed at improving threat detection, situational awareness, and survivability across multiple aircraft platforms. Future efforts will focus on integrating multi-spectral sensors and evolving.

The ASE systems, such as the Next Generation Pointer/Tracker, meet emerging threats and enable interoperability with future platforms. Continued science and technology investments will drive the development of ASE capabilities, ensuring seamless integration into digitally connected networks like the MANGL.

Marine Aviation Enablers

The Marine Air Command and Control System is undergoing significant modernization with new equipment like TPS-80 Ground/Air Task-Oriented Radar, Common Aviation Command and Control System (CAC2S), and Marine Air Defense Integrated System to enhance air battle management, integrated air and missile defense, and multi-domain C2 capabilities. The CAC2S processes and integrates data from sensors and aircraft to support Marine, Naval, and joint aviation operations, while the CAC2S Small Form Factor variant and the Theater Battle Management Core System provide scalable, modern capabilities for distributed command and control.

The Marine Corps is expanding its groundbased air defense capabilities through systems like MADIS, Light-MADIS, and the Medium Range Intercept Capability to defend against a range of aerial threats, supported by the growth of the low altitude air defense community and future participation in the Army’s interceptor development efforts.

Aviation ground support ensures Marine Aviation’s expeditionary capability, providing essential services like airfield construction, aircraft recovery, and refueling at austere locations, supporting advanced base operations and distributed aviation.

The AC2GS funding priorities focus on improving air traffic control and aircraft launch and recovery capabilities, including precision landing systems, inter-facility communications, and airfield lighting. Additionally, funding is directed toward sustaining and enhancing green-dollar air C2, air defense programs, and aircraft rescue and firefighting equipment to ensure readiness and interoperability across joint and naval operations.

4th Marine Aircraft Wing

The 4th MAW plays a vital role in enhancing the MAGTF’s global readiness and flexibility by providing a reserve aviation force capable of responding to emerging threats. This force ensures that the Marine Corps maintains operational depth, which is critical for addressing the evolving demands of modern warfare.

The 4th MAW works closely with active components, strengthening aviation readiness through ongoing support and collaboration with 1st, 2nd, and 3rd MAW units. By transitioning to advanced platforms like the F-35C, KC-130J and tiltrotor aircraft, and integrating rotary, unmanned, and expeditionary aviation enablers, the wing ensures a unified and adaptable force structure ready for global missions.

Expeditionary & Maritime Aviation-Advanced Development Team (XMA-ADT)

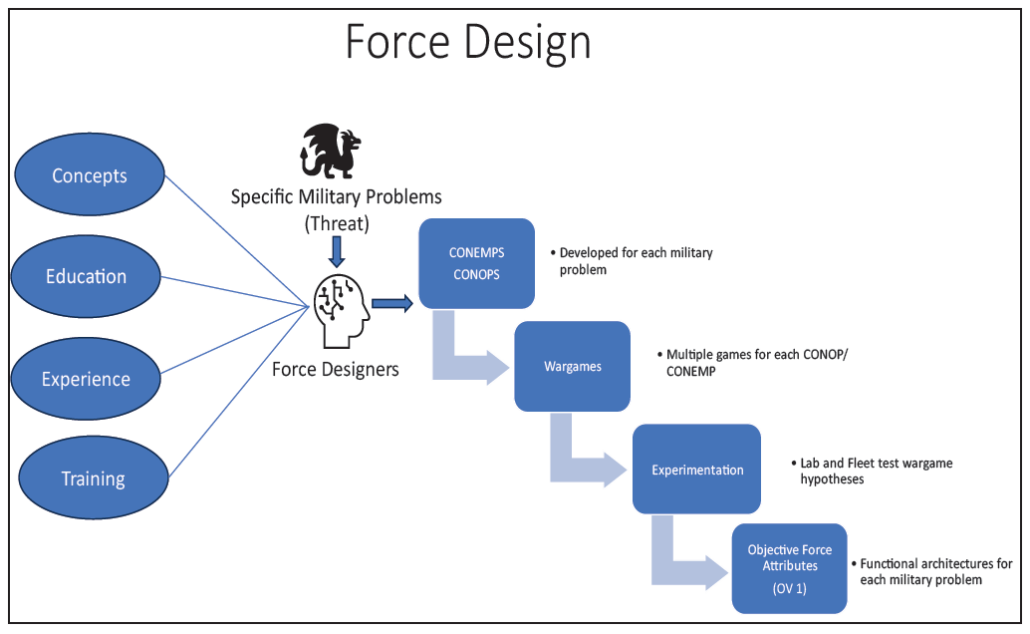

The XMA-ADT, established in August 2023, accelerates the acquisition of technologies for Force Design by coordinating with stakeholders and employing operational prototypes to address critical capability gaps in Marine Aviation. In 2024, XMA-ADT focused on enhancing capabilities for Marine Aviation, including MUX TACAIR, Airborne Logistics Connector, Precision Attack Strike Missile, and H-1 Next, with key milestones such as UAS Manned-Unmanned Teaming and successful flight demonstrations for each project. In 2025, XMA-ADT will refine capabilities for MUX TACAIR, continue Airborne Logistics Connector demonstrations with plans for Weapons and Tactics Instructor Course 1-26, and further develop the Long-Range Attack Missile toward achieving a maximum range live-fire shot by the end of the year.

In summary, Marine Aviation continues to be forward deployed and operate from expeditionary sites, joint locations, Navy ships, and strategic main operating bases. As we actively campaign, our focus on balancing today’s readiness with tomorrow’s modernization is critical as we continue to compete, assure our allies and partners, and deter our adversaries. This balance cannot be achieved without direct investment in our Marines, sailors, and aircrew. Their training must be relevant, realistic, and accomplished in the best aircraft and equipment available. Marine Aviation stands ready to fight and win today and into the future.