Tribute to a Vietnam War Marine

By: Capt James P CoanPosted on August 15, 2024

Executive Editor’s note: The following article received second place in the 2024 Leatherneck Magazine Writing Contest. The award is provided through an endowment by the Colonel Charles E. Michaels Foundation and is being given in memory of Colonel William E. Barber, USMC, who fought on Iwo Jima during World War II, and was the recipient of the Medal of Honor for his actions at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir during the Korean War. Upcoming issues of Leatherneck will feature the third-place winner and honorable mention entries.

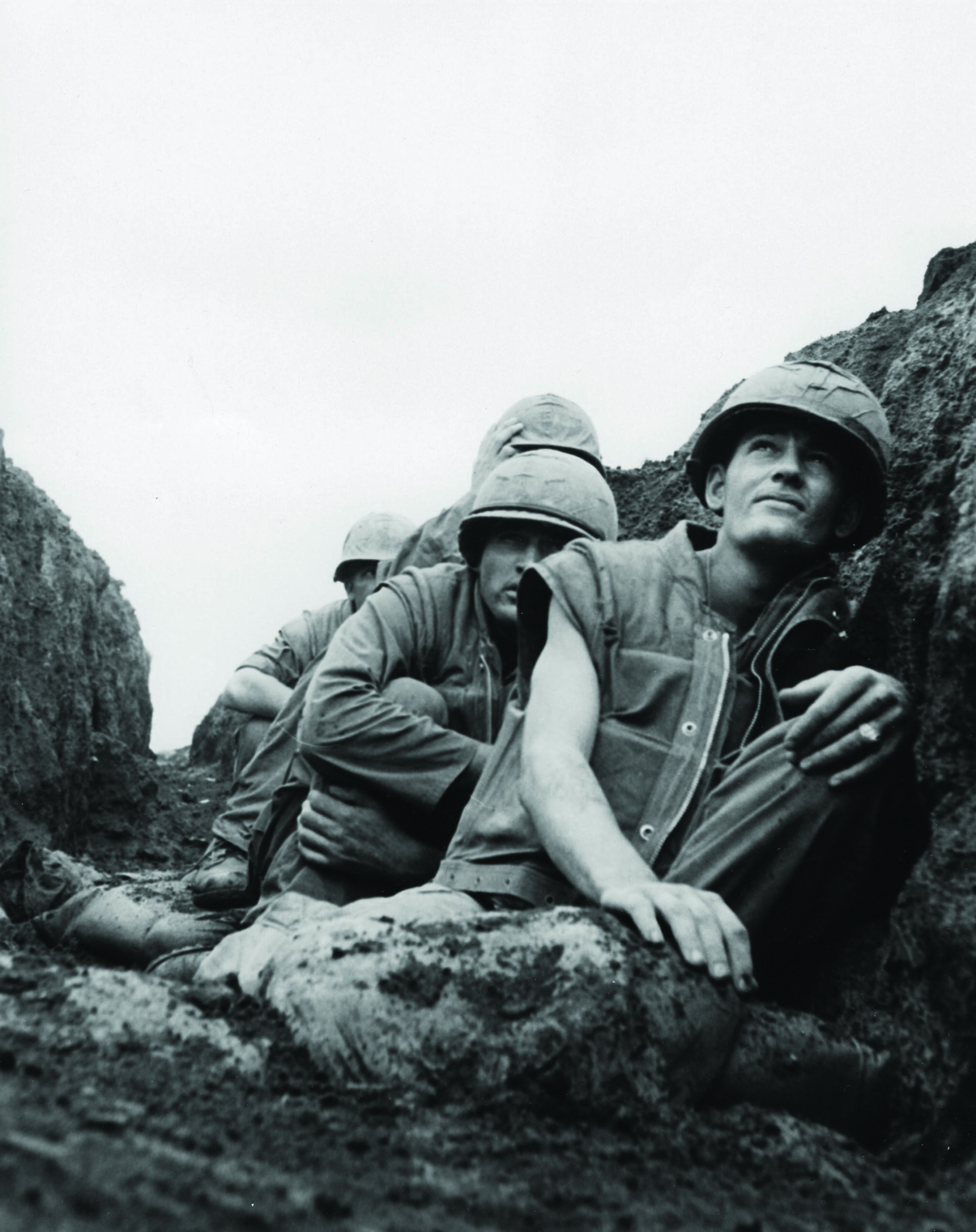

From the spring of 1967 through mid-1969, a firebase named Con Thien, located 1.5 miles south of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) dividing North and South Vietnam, was the scene of fierce combat between the U.S. Marines and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). The Marines would hold Con Thien “at all costs,” but the cost was high. By the time the firebase was turned over to the South Vietnamese Army in 1969, 1,400 U.S. Marines and Navy corpsmen had sacrificed all their tomorrows and more than 9,000 were wounded.

I arrived in Vietnam in August 1967, a recent graduate of the Marine officers tracked vehicle training course at Camp Pendleton, Calif. After a brief stint at the 3rd Tank Battalion Headquarters outside of Phu Bai, I was called into the colonel’s bunker one day where I was informed that I was being transferred up to Con Thien to take over command of “Alpha” Company’s 1st Tank Platoon. I was going to replace the tank platoon commander there who had been wounded twice by NVA artillery in 10 days.

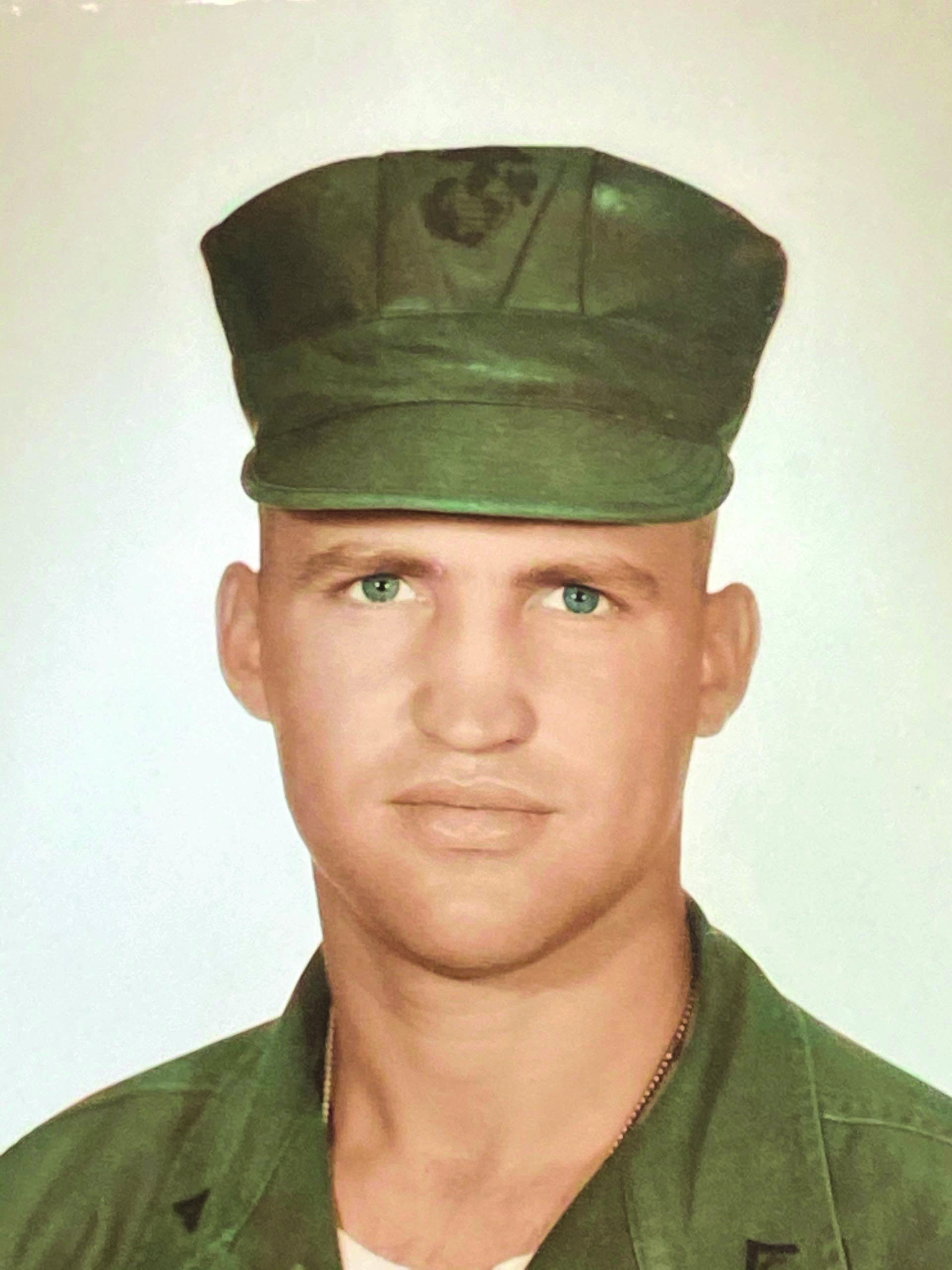

Sept. 10, my first morning on Con Thien, I ducked into the tanker bunker to introduce myself when I was greeted by a tall Marine who said, “Welcome to the fighting first platoon, sir!” He then stabbed his bayonet into a warm can of beer and offered me a swig. I remember thinking as I managed to down the warm beer without gagging on it, “All right! I’ve found a home here.”

The Marine who first greeted me was Albert “Bert” Trevail, a 24-year-old lance corporal who had served one tour in the Canadian Army. He then tried college but didn’t enjoy academia, so he came to America, joined the U.S. Marines, and got his wish to be sent to Vietnam. He was the driver on my tank and had been at Con Thien for a month before I arrived. When I mentioned needing to meet with the platoon sergeant, Trevail sat me down and explained what dangers I had to be aware of and how and when it was safe to make any trips on foot around the perimeter. No doubt, I owe my survival during my 40 days under siege at Con Thien to Trevail’s tutoring of his “new-boot second lieutenant.”

Every afternoon, all unit leaders were required to attend the 3/9 CO’s daily briefing at 4 p.m. During one briefing, we twice dove out of our chairs due to several close incoming rounds of artillery fired from the DMZ. When the briefing ended, I waited until it was quiet, then sprinted over to my bunker.

Bursting in through the entrance, I noted my crewmen were all sitting hunched over in silence, dejectedly staring at the floor. That’s when I learned that one of the incoming artillery shells had scored a direct hit on the bunker next to ours, critically wounding two Marines. Trevail had ignored the threat of more incoming, rushed over to the two wounded Marines, loaded them on our tank by himself, then drove the tank over to the Battalion Aid Station, likely saving their lives. I made a report on Trevail’s act of bravery under fire to my company commander back in Dong Ha, but never heard any more about it.

My third evening on Con Thien, it was my tank’s turn to spend the night on the northern perimeter. Around 3 a.m., I was asleep on my tank’s rear deck when I was jarred awake by snapping and popping noises zipping over the tank. We were under attack! Flares floating down from overhead revealed numerous enemy figures charging towards our perimeter wire. I jumped inside the tank turret and ordered the crewmen to open fire with our weapons—the 90mm main gun and the .30-caliber coaxial machine gun. But my own cupola-mounted .50-cal. machine gun jammed. Sitting up forward in the driver’s seat, Trevail heard me cursing out my gun. He chose to open the driver’s hatch, expose his head and shoulders to enemy fire, and open fire with his .45 pistol and the M14 rifle he kept (against regulations).

The word was soon passed to cease fire. In the dwindling flare light, numerous NVA bodies lay unmoving on the ground before us. None of them had been able to breach the inner perimeter wire. At daylight, the 3/9 CO and XO were making the rounds of the northern perimeter when they stopped beside our tank. “You tankers did a great job last night, lieutenant,” said the colonel. I thanked him on behalf of my tank crewmen. I would also inform my company commander about Trevail’s bravery under fire. Unfortunately, the captain was soon relieved of duty due to some questionable decisions he had made, so my report on Trevail never saw the light of day.

Several months later, after Trevail had made corporal and was promoted to tank commander, we were back up at Con Thien for another 60-day stay. It was a sunny, warm spring day when I was told to mount up my platoon and head out the south gate. A Marine patrol had walked into an ambush southwest of Yankee Station. As my three tanks got in line and charged at the enemy position, an NVA soldier leapt out from behind a shrub and opened fire at Trevail’s tank with his AK-47 rifle. Nearby Marines immediately shot down the NVA soldier, so I believed he had missed Trevail. As my tanks reached the abandoned NVA bunker position, I pulled my tank up next to Trevail’s tank expecting to tell him, “Nice work, Corporal.” That’s when I noticed a bloody bandage wrapped around the side of his face as he was helping hoist an injured Marine up on his tank.

I said in no uncertain terms, “Trevail, you get on over to the medevac area … now!!” He replied, “Sir, I can’t leave these Marines out here.” I replied again, “Bert, that is an order! Now, move out!” He did as ordered but didn’t climb aboard a medevac helicopter until after all the wounded Marines carried on his tank were safely medevacked.

Later that same morning, I rode my tank to our company headquarters in Dong Ha to make a full report on my reaction force attack on the NVA ambush site. I decided to stop in at Delta Med and see how Trevail was doing. He was sitting at a table by himself, his head all bandaged. When he saw me, he jumped up and begged me to take him out of there and back up to Con Thien. I told him I could not do that without the head corpsman’s permission. I told him to enjoy the hot chow, hot showers, and clean sheets to sleep on. But he wanted no part of it. Excusing myself, I left and went over to the Alpha Company CP to report in. Later, after a delicious hot lunch at 9th Motor Transport, my crewmen and I mounted our tank and headed back up the road to Con Thien. As I stepped down into our bunker, who should greet me with a sheepish smile but Cpl Trevail.

“T-Trevail! H-how … how?” I stuttered, totally dumbfounded. I did not know whether to chew him out or what. I decided to stay calm and ask him why he was not still back at the hospital. He stated that when he noted a truck convoy forming up outside of Delta Med, he walked out and approached a truck driver, asking him where they were headed. When the driver said “Con Thien,” Trevail asked permission to climb aboard and the driver said, “Sure!”

I did not know what to do. Here was a Marine who would rather be with his buddies in a dangerous place where he would risk getting hurt or worse at any moment than live comfortably for a week in a relatively safe, secure location in the rear. I radioed my company commander back in Dong Ha, told him what Trevail had done, and asked for advice. The captain told me he would cover for Trevail, saying he misunderstood the doctor’s instructions. I thought I heard a few muffled chuckles in the background.

In mid-July, 1968, the entire 9th Marine Regiment embarked upon an incursion into the southern half of the DMZ. My five-tank platoon was attached to G/2/9. As we moved out in attack formation toward a North Vietnamese bunker complex, the enemy opened up on us with a mortar attack. One of my tanks drove down into a 2,000-lb. bomb crater caused by a recent B-52 strike and was stuck in the loose dirt at the bottom. All my tanks halted in place while I tried to think how to undo this dilemma. The infantry company commander was on the radio, yelling at me to get my tanks moving. I told him I couldn’t leave one of my tanks behind. Just then, Trevail pulled his tank up to the edge of the crater, jumped to the ground and unhooked his tow cable. Ignoring the enemy mortar shells impacting nearby, he dragged that heavy, steel tow cable down to the stuck tank and hooked it up. Then he climbed out of the crater and ground-guided the stuck tank out of the crater. We were able then to resume the attack. I subsequently wrote Trevail up for a Bronze Star medal and he received it, as well as a meritorious promotion to sergeant.

I rotated stateside two months later. Trevail extended for two more tours in Vietnam. He remained on active duty for 20 more years, retiring as a master sergeant. Years later, I encountered him through our membership in the USMC Vietnam Tankers Association. I learned that he had gone back to college, achieved his teaching certificate, and was working at a Sacramento, Calif., high school as a computer science instructor. Sadly, Albert Trevail is no longer with us, having passed away a few years ago. He will always remain in my heart and mind as the most outstanding Marine Corps warrior that I was fortunate to have served with in Vietnam. I personally witnessed his courage under fire numerous times, often when coming to the aid of other wounded Marines.

Author’s bio: Capt James P. Coan served three years active duty in the Marine Corps and three years in the Reserves before being honorably discharged in 1972. Coan had a 30-year career with the California Youth Authority before retiring to Arizona near his hometown of Tucson. Coan is the author of two books: “Con Thien: The Hill of Angels” and “Time in the Barrel: A Marine’s Account of the Battle for Con Thien.” Coan is a life member of the USMC Vietnam Tankers Association, VFW, Military Order of the Purple Heart and Marine Corps League.