To the Shores of Tripoli

By: Mike MillerPosted on November 15, 2024

One of the first international challenges facing the newly formed United States in the 19th century came from the Barbary States on the northern coast of Africa and their lucrative business of state-sponsored piracy. In 1804, President Thomas Jefferson seized an opportunity to split the leadership of the Tripolitan pirates, forging an alliance with Hamet Karamanli, the former bashaw of Tripoli. Expelled by his brother, Yusuf, Karamanli desired a return to the throne. The United States supported the overthrow of Yusuf in exchange for a favorable treaty with the Barbary States.

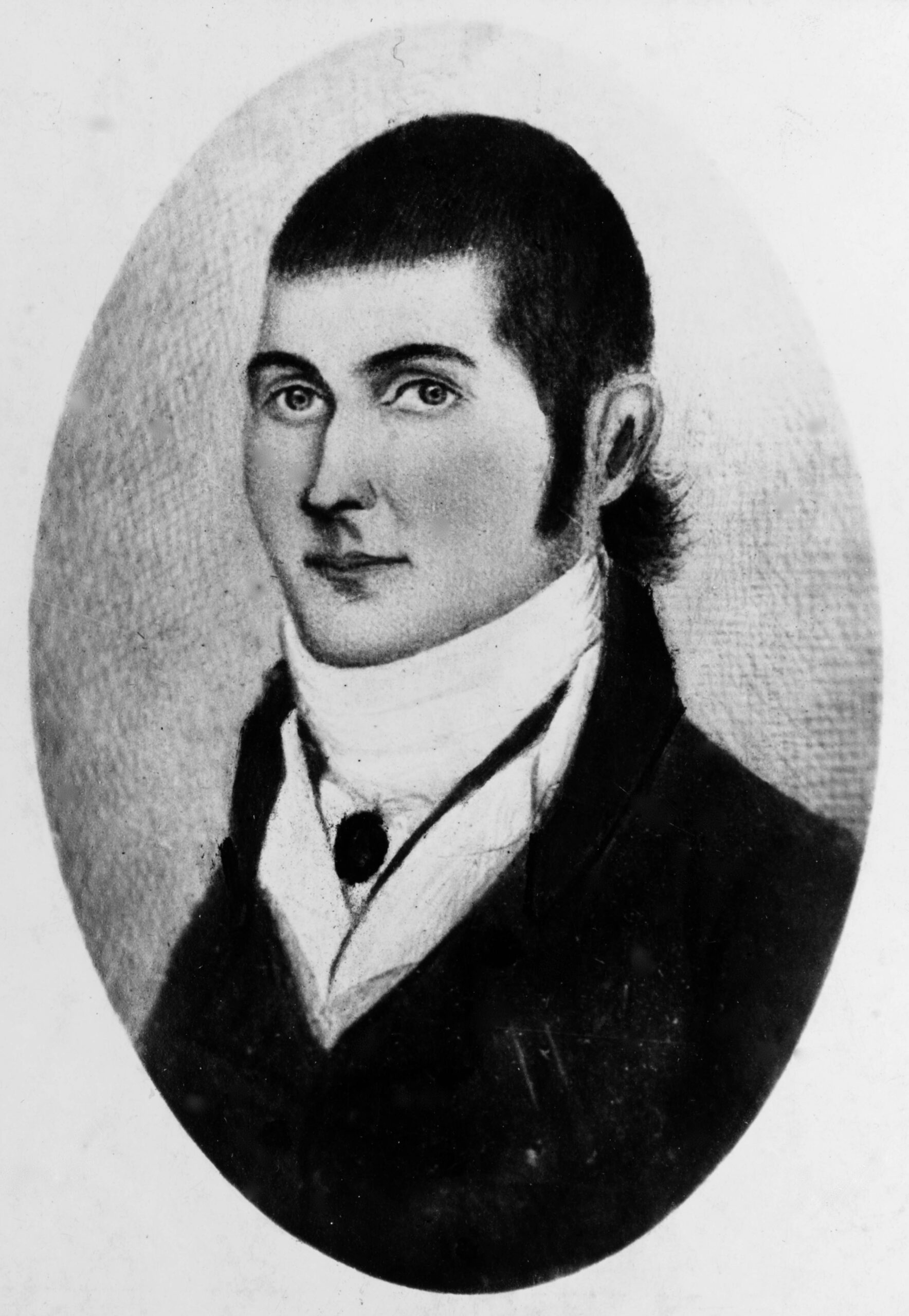

William Eaton, a former Army officer, was appointed United States Navy Agent for the Barbary Regencies. It was his responsibility to negotiate with the unmanageable North African states and expedite the transfer of power in Tripoli by force. Eaton planned an audacious expedition to capture the fortified city of Derna, one of the wealthiest cites in the Tripolitan region. In taking Derna, the road would lie open for further advance to the capital city of Tripoli, and ultimately return Karamanli to the throne over one of the most powerful Barbary States. However, Eaton’s expedition required traveling over 400 miles through the unforgiving desert to reach the objective.

Eaton requested the American warships of Commodore Samuel Barron’s naval squadron in addition to 100 Marines. He was denied the men. Under his authority was Lieutenant Presley N. O’Bannon, who requested 20 Marines from his own command over USS Argus. He was allowed only six. Corporal Arthur Campbell and Privates Bernard O’Brian, David Thomas, James Owen, Edward Stewart and John Wilton were selected for the incredible 400-mile journey.

The selected six were relative newcomers to the Marine Corps, all having enlisted in 1803 and served on USS Argus for almost all of their enlistment. Private Thomas was typical of the men selected, having been promoted to corporal on Sept.10 of that same year and returned to the rank of private nine months later for being “drunk in quarters.” Bernard O’Brian reached the rank of corporal during the expedition but reverted back to private several months later as well.

Knowing what awaited him at Derna, and the unpredictable qualities of his own hired Bedouins, Eaton again requested more men for the expedition, repeating his requirement for 100 Marines with bayonets to “place the success beyond the caprice of incident.” He was again denied. Lieutenant O’Bannon and his six Marines remained the American support for the expedition, leaving just 14 Marines on the Argus.

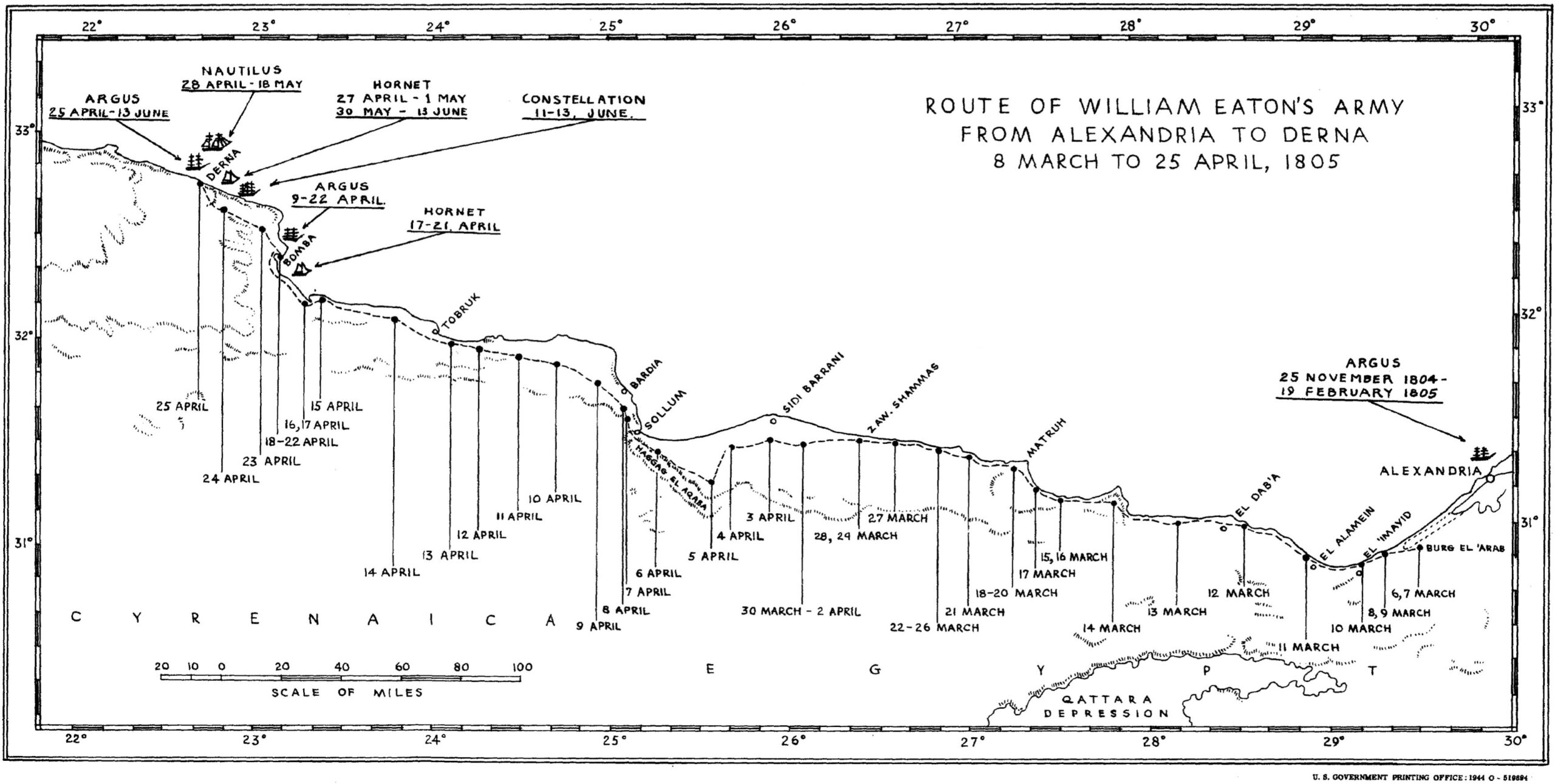

On March 6, 1805, Eaton’s “band of brothers” began their march for Derna. The colorful procession was composed of 12 nationalities, offering a picturesque view of approximately 300 Bedouin cavalrymen leading the journey and 70 Christian Egyptians recruited by Eaton at Alexandria and 67 Greek mercenaries, interspersed with 190 camels bearing supplies. Lieutenant O’Bannon and his six Marines joined the march, accompanied by two Navy midshipmen, George W. Mann and Pascal Paoli Peck. The unusual column’s first day’s march proved impressive, making it 40 miles before halting for camp. But they were initiated into the reality of what awaited them on the road to Derna when their water source turned up dry.

“Here commenced the first of our sufferings,” recalled Midshipman Peck. “After marching near 40 miles in burning sun, buoyed up with the idea of finding water at the end … not the least sign of water, nor was a green thing to be seen.” The next morning, a search discovered a nearby supply of putrid water. Little worried about the questionable nature of the water, the men considered it rejuvenating, declaring it “more delicious than the most precious cordial.” The column trudged on.

Several times in the coming days and weeks the Bedouins refused to move on without pay or venture further into the desert, leaving the Marines stranded. Unfortunately, deals made in the desert were more suggestions than contracts; they drained Eaton’s available cash supply. Even when Karamanli’s men received pay, they departed with it to Cairo. Eaton’s plan to reach Derna seemed doomed to fail.

Eaton tried to calm the remaining Bedouin leaders by promising the arrival of American warships at Bomba, but they declared no further movement would be made until a messenger confirmed the ships’ arrival. Eaton’s response was emphatic. He furiously ordered all rations cut off from them. The small but potent detachment of Marines shaped the backbone of the security, ready to protect the American supplies and put an end to any further duplicity as they waited for messengers from the American Naval Squadron.

“I left the Arab Chiefs in the Bashaw’s tent confused and embarrassed,” Eaton wrote in his journal that night, “and retired to my own markee and reflections.” The American mission seemed hopelessly stuck in the desert, far from help. “We have marched a distance of [200] miles,” Eaton recorded, “through an inhospitable waste of world without seeing the habitation of an animated being, or the tracks of man … o’er burning sands and rocky mountains.” However, fortune favored the Americans when Karamanli’s remaining Bedouins considered their choices of starvation or marching, and agreed to rejoin the expedition.

Better news arrived on April 6 as Eaton’s men discovered the welcome but stagnant liquid of a well, dug 70 feet into the ground. The dubious contents, “feted and saline,” caused some concern, but Eaton’s horses were thirsty, having had no water for 42 hours, and the men had had only a single drink of nauseating water the night before. Overwhelming dehydration became the driving force of both man and beast as they crowded together around the well. Their frantic efforts toward being the first to gain access to the brackish liquid resulted in tragedy, when a horse slid backwards through the crowd, crashing into the well. The fall killed the horse instantly, but the crowd drank anyway.

The combination of hunger and thirst tested even the strongest men. Doubts of the ships’ arrival at Bomba grew with every disappointment.

Karamanli grew suspicious and dispatched couriers on his own to contact the American squadron, supposed to be at Bomba. Eaton was outraged at this turn of events, knowing only six more days of rice remained. He insisted the march must continue or they would starve, but the bashaw and his chiefs vowed to proceed no further. Eaton countered by cutting off the rice supply, causing them to recognize hunger as the major flaw in their power play.

When the Bashaw made a show of packing up his tent and baggage, beginning his own march, Eaton noted that he “waited without emotion the result of this movement” as not to “betray a concern for ourselves.” Calm handling of the situation allowed him to discover the bashaw’s plan to capture all of the provisions for the Bedouins.

Eaton’s drummer beat the call to arms, bringing Lieutenant O’Bannon’s Marines into line before the supply tent to defend the invaluable rice. The Christian Egyptians joined the seven Marines, as they had few options in the middle of a barren desert. Two hundred of Karamanli’s cavalrymen drew up in a show of force. The opposing forces faced each another for one hour, each side reluctant to be the first to open fire.

As if on cue, the bashaw appeared with his entourage, dismounted, and raised his tent, as a message that he would now stay. He convinced the Bedouins to withdraw from the field, ending the confrontation. Eaton ordered O’Bannon and his Marines to go through the manual of arms as a sign the Americans were also standing down. The Bedouins watched the Marines and immediately roared, “The Christians are preparing to fire on us!” The bashaw leapt back on his horse, calling out to his people, “For God’s sake do not fire! The Christians are our friends.”

Despite his best efforts, the 200 cavalrymen charged across the field at a full sprint. Most of Eaton’s demoralized Greeks ran, leaving the American Marines on their own. “Mr. O’Bannon, Mr. Peck, and young [British mercenary Richard] Farquhar stood firmly by me,” Eaton recalled. The charging horsemen halted only a few feet away from the small band of loyal Marines, allowing time for Eaton an attempt again to end the confrontation. Farquhar stood in the midst of the crowd, receiving a pistol thrust against his chest, but the weapon misfired, leaving him unhurt. A clamoring swarm of voices erupted, drowning out any attempt to enforce order before a single accurate shot would initiate a fatal battle in the middle of the desert.

With drawn swords, the bashaw’s officers rode into the melee. They forcefully separated the two sides, preventing the impending slaughter. Eaton chastised Karamanli for generating the clash. “The firm and decisive conduct of Mr. O’Bannon, as on all other occasions, did much to deter th[ose] by whom we were surrounded,” Eaton confided in his journal, “as well as to support our own dignity and character.”

On April 9, the column advanced peacefully, traveling 10 miles toward the salvation of the American warships at Bomba. They were lucky enough to locate a water cistern containing potable water. The column made camp near the water among the ruins of ancient houses and walls, perhaps portending their own ruin. Worse was the discovery of two swollen, rotting corpses in the well. They were thought to be murdered by local tribesmen, but Eaton confided in his journal: “We were obliged nevertheless to use the water.”

They traveled another 10 miles on April 10, where they came upon a picturesque valley with water at last untainted by death. The men were starved now, existing on half rations of rice alone. Apprehension arose in camp, centered on whether the supply ships had arrived in Bomba Bay. Eaton countered the starved panic by calling a council of war addressing the collapse of his command. Some of the bashaw’s people would not take another step without proof of the arrival of the ships at Bomba. Eaton countered with a two days’ march followed by a halt to await the messengers dispatched to find the ships. With only handfuls of rice left and no hope of gaining more from the bleak countryside, Eaton, O’Bannon and the Marines gambled three days would somehow prevent an uprising by the starved members of his command.

The arrival of the ships “alone will prevent a revolt among our Arabs,” Eaton wrote, “who undoubtedly take any side which will give them the best fare.” If rebellion erupted, Lieutenant O’Bannon and his six Marines faced tall odds for survival. A massacre in a lonesome ravine would end a bloody chapter in the American effort to suppress the piracy of the Barbary States.

A mutiny began that evening, when Greek cannoneers demanded their share of provisions. Eaton confided only in Lieutenant O’Bannon the gravity of the situation. He dispatched a messenger to inform the insurgents “on pain of death, not to appear in arms to make any remonstrances with me.” With deadly confrontation to break out at any moment, the Bomba messenger returned with word of the presence of supply ships. The mood in camp changed instantly to celebration.

The bashaw assured Eaton he would lead his men to Derna. At 9 p.m., however, the only one not celebrating was the bashaw, who began a series of “spasms and vomiting,” which “continued the greater part of the night.” Eaton continued his expedition 6 more miles toward Bomba before establishing camp without water. The halt resulted when Karamanli could go no further.

His Excellency the Bashaw Yusuf of Tripoli finally took an active interest in his brother’s invasion force on April 12, moving closer to his stronghold at Derna.

Captain William Bainbridge, commanding the blockading squadron off Tripoli, received an angry message from Yusuf, acknowledging his “particular resentment” of his brother traveling with the American expedition. He threatened his American prisoners with death. Marine Captain John Hall, Lieutenants William S. Osborne, Robert Greenleaf and John Howard and 44 enlisted Marines were part of American captives taken during the disastrous capture of USS Philadelphia. The prisoners were informed that “if the Americans drove him to extremities, or attacked his town, he would put every American prisoner to death.”

Bashaw Yusuf might have been less concerned if he had known of the true condition of the American invasion force. The last rice had been consumed raw. Starvation plagued the camp. The bashaw allowed one of his camels to be slaughtered to feed his men, trading another to the Bedouin families for one of their sheep. Full rations of camel and sheep were provided to the hungry Marines, but “they were without salt or bread” to make it more appetizing. The fresh meat allowed the column to continue the march to Tobruk, but a daily loss of pack animals meant eventual disaster. The only choice remaining was to reach Bomba Bay at any cost.

On April 15, Captain Samuel Barron ordered Master Commandant John H. Dent to proceed with his schooner, USS Nautilus, to establish communication with Eaton. Dent found no sign of the expedition, as the coastline proved desolate. With no word from Eaton, disaster seemed a logical conclusion. Without knowledge of Dent’s foray, Eaton’s prospects were bleak. as the day of USS Nautilus’s departure, Eaton and his starving command finally reached the Mediterranean Sea. Their excitement quickly vanished as they gazed at an empty sea.

“What was my astonishment,” Eaton admitted, “to find at this celebrated port not the trace of a human being, nor a drop of water.” Three locals claimed they saw two ships in the bay a few days before, but they departed without landing. The famished Bedouins saw yet another betrayal in Eaton’s promises, who “abused [them] as imposters and infidels,” and “all began now to think of the means of individual safety.” The collapse of Eaton’s promises erupted in disparate overnight discussions by all factions of the expedition. Lt O’Bannon’s Marines remained resolute, but few others could be depended on.

The Bedouins threatened to depart the following morning, but Eaton somehow yet again persuaded everyone to continue toward Derna. He took the Christian members of his command to a high point above the bay, kindling fires all night to signal to any ship passing in the night that the expedition was there at Bomba, waiting for support.

The morning of April 16 dawned with a hunger-fed depression, followed by the breakaway of some of the Bedouins. A final messenger rode up the high mountain for one last glimpse across the sea. Incredibly, the sails of the USS Argus appeared!

Eaton wrote, “Language is too poor to paint the joy and exaltation” in every person in the camp, including Lieutenant O’Bannon and his Marines. Overjoyed, Eaton went aboard to confer with the Navy officers over the path ahead.

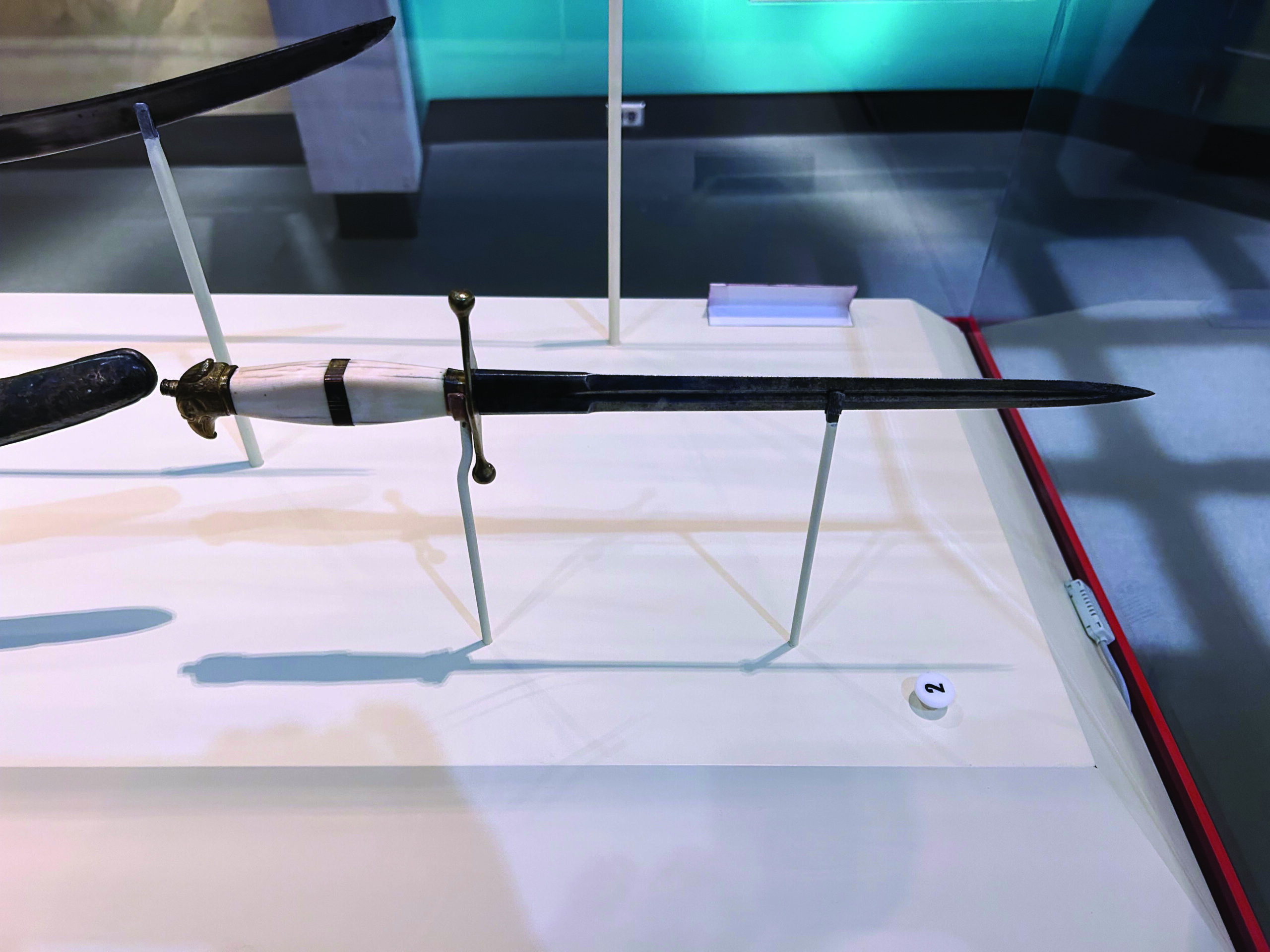

Seven thousand Spanish dollars were transferred by Master Commandant Isaac Hull to Eaton, ensuring the travelers remained loyal to the United States. Perhaps believing his role in the attack might prove fatal, Eaton gave Hull his cloak and small sword in thanks for his support and requested his Damascus sabre and gold watch be sent to Captain Barron, “due to his goodness and valor.”

But Eaton faced a new challenge when Hull unexpectedly ordered Lieutenant O’Bannon and his Marines back on USS Argus. O’Bannon penned a letter requesting permission to continue with the expedition at least “during his stay on land, or, at least [until] we arrive at [Derna].” Navy Ensign George Mann also requested to accompany Eaton, “by a wish to contribute generally by my services to the Interest of my Country.” Hull granted the requests in exchange for the return of Midshipman Peck. More than pleased to depart, Peck recalled the hardships as he sailed away. “We were very frequently 24 hours without water, and once 47 hours without a drop … for the space of 450 mile we saw neither house nor tree, nor hardly anything green, and, except in one place, not a trace of a human being.”

On April 23, the expedition left camp for the final 60 miles to Derna, led by O’Bannon’s ever faithful Marines. They soon encountered the welcome sight of cultivated farmland and a natural spring. The column made 15 more miles the following day, marching under the shade of huge and beautiful red cedar trees, the first trees of any semblance to a forest since they began their journey. Eaton camped that night only five hours from Derna.

A courier entered the camp, confirming the near arrival of enemy reinforcements from Tripoli, joining the forces already defending the city. “Alarm and consternation” overwhelmed the Bedouin chiefs and the bashaw into a private night conference, to which Eaton was not invited. However, the American consul had problems of his own. No further advance could be made as a fierce storm scattered the American warships. And no attack could be made without their cannons. Coordination between the American forces on land and sea was critical for any hope of success.

(Leatherneck file photo)

On April 25, drummers woke the sleeping Marines and men at 6 a.m., just as Eaton issued orders for the day’s march to finally close on Derna. “The Arabs mutinized,” Eaton wrote later, “The Sheiks il Taiib and Mahomet at the head of the Arab cavalry took up a retrograde march, and the Bedouins refused to strike their tents.” Only Lt O’Bannon’s Marines and the Greek mercenaries stood ready to march to Derna. Once again, failure seemed immensely possible, despite the many weeks of travel over 400 miles of desert misery. For the first time, the realization of combat loomed, giving pause to many in the expedition.

Eaton quickly but skillfully navigated the various hazards of the morning, satisfying the concerns of his men with persuasion, negotiation, and $2,000 dollars issued to various leaders. Lt O’Bannon and his Marines watched the proceedings carefully, made the march as planned, and occupied a knoll with a commanding view of the city and the Mediterranean Sea beyond. Despite all of the trials and tribulations which would have frustrated commanders from any era, Eaton’s expedition finally arrived within sight of the rooftops of Derna.

Eaton’s perch above the city allowed for a quick assessment of their task ahead. A water battery of eight formidable 8-pounder cannon looked ominous to naval attack while a fort on a nearby hill overlooked the city, commanding the American approach to the city. Hastily built breastworks interlocking with the walls of old and new buildings along the bay were filled with firing positions. The governor’s palace was defended by a 10-inch howitzer positioned on the terrace, defending the city in all directions.

Several of the Derna Sheikhs came to the American camp in the evening, swearing their loyalty and that of two thirds of the city’s population to Hamet Karamanli. However, they warned the party that the governor boasted of 800 soldiers supported by formidable artillery, soon to be strengthened by Yusuf’s reinforcements approaching from Tripoli. Worst of all, the waves of the Mediterranean Sea revealed no sign of those essential American warships. Even Karamanli looked extremely nervous, perhaps desiring to walk “himself back to Egypt.”

Retreating 441 miles to safety was never an option, nor was a frontal assault on a fortified city defended by superior numbers. Eaton reviewed the cards of chance which had been dealt to him and came up with yet another option—that of diplomacy. “I want no territory,” Eaton wrote to Governor Mustafa, who oversaw the defenses of the city. “With me is advancing the legitimate Sovereign of your country. Give us a passage through your city; and supplies of which we shall need you shall receive fair compensation.” He assured the governor that his position would remain the same and offered, “Let no differences of religion induce us to shed the blood of harmless men who think little and know nothing.”

A message soon arrived from Mustafa, wasting few words in reply: “My head or yours.”

Good fortune favored Eaton and O’Bannon once again. The welcome sight of approaching sails changed the course of events at Derna yet again. Master Commandant Dent arrived, guiding USS Nautilus close to shore. “Make my respects to O’Bannon,” Dent signaled, “and all of your followers and wishing you all the success you so fully deserve.”

“I expressed my determination to attack the town tomorrow,” Eaton wrote that night, “if the other vessels came in seasonably.” With or without the essential gunfire from the sea, the dominant fort must be captured before any further progress could be made inside the city walls. Providence again interceded, with the arrival of USS Hornet and USS Argus arriving at 5:30 a.m. on April 27.

The break of dawn revealed all three warships in tandem, ready for combat.

Alarming intelligence reached Eaton that morning, indicating a large relief column of Tripolitan soldiers approaching. This column was estimated to be only two days and 14 hours’ march away from the city, leaving no time for delay by the Americans. Understanding victory this day was absolutely essential, Eaton prepared to take the head of his opponent, Mustafa, along with his city. Orders sent the Marines and men advancing toward the walls of Derna, comforted by the presence of the three warships in position as close to land as they could be, daring the enemy cannons to fire.

A good wind coming offshore allowed the Nautilus and Hornet to anchor close to Derna’s oceanfront, where they unloaded supplies for Eaton, including both of the cannon rowed ashore in small boats “with much difficulty.” Sailors then hauled one of guns up a steep downslope of boulders but left the other gun behind on orders from Eaton, who feared the time expended would result in “losing this favorable moment of attack.”

The mass of Marines, Bedouins, Greeks, Egyptians, and Christians reached their forward positions without dispute, while Navy Lieutenant Samuel Evans maneuvered the Hornet to within 100 yards of the formidable water battery, anchoring on the seaport side of Derna. Evans immediately open fire on the Tripolitan cannons at pistol range, guaranteeing the gunners would hardly miss their targets. The fair winds allowed the Nautilus to anchor close to shore as well, where he unleashed a continuous barrage against the now beleaguered battery.

Lieutenant Evans’ duel with the water battery proved epic, challenging his 6-inch brass guns against the heavy 9-pound cannon of the fort. Both sides traded volleys, with Evans spraying the Tripolitan gun crews with grapeshot, silencing the heavier cannon in 45 minutes. However, one of the enemy shells cut the Hornet’s flag from the halyard. Navy Midshipman Samuel G. Blodgett gathered the flag and climbed into the rigging, nailing the colors to the mainmast.

Blodgett’s foray provided an easy target for the enemy marksmen on the wall, but he escaped harm from the hail of musket balls passing through the sails around him. One lucky bullet lodged in his pocket watch chain, saving his life. At the same time, Commandant Hull maneuvered Argus to a position just to the south of Dent close to shore, dispatching shell after battering shell into the city. His 24-pounder cannon proved particularly effective in lobbing projectiles into the streets, scattering both soldiers and townspeople.

Covered by the warships’ fire, Lieutenant O’Bannon led the ground assault on the left, taking position under the cover of a hill overlooking the main body of Mustafa’s infantry. Eaton held the ground between O’Bannon and the sea with a small detachment of Christian infantry. Curiously, the Hornet’s six Marines, Nautilus’ 17 Marines and the 15 Marines of O’Bannon’s own detachment of Argus remained aboard ship.

O’Bannon and his six Marines, 24 artillerymen, 26 Greek mercenaries and a scattering of Bedouin cavalry gazed across the open ground, sizing up the opposing defenders. The Marines positioned themselves to face the newly dug parapets and a sheltered ravine on the southeast side of the city. As a backdrop of shells tore into the city from the American warships, O’Bannon observed another threat to the southwest. Mustafa’s men defended an old castle, supported by a body of cavalry deployed on the plain beyond. These flanking forces thankfully remained out of the fight.

The intensity of the shelling reached a crescendo just before 2 p.m., striking everywhere the Tripolitans showed themselves. Forty-five minutes of constant fire silenced the sea battery, forcing most of the supporting infantrymen to disperse. The walls were still held by the bravest soldiers, clinging tightly to their positions. Another threat emerged in front of Eaton’s Christian detachment along the coast, however, forming their “most vulnerable point.” The cannon hauled ashore from the USS Nautilus was no longer effective. In the excitement of battle, the gunners fired the rammer along with a shell into the city.

Rifle fire from the city intensified on the attackers. “Our troops were thrown into confusion,” Eaton noted, “and undisciplined as they were, it was impossible to reduce them to order.” The assault stalled as the whine of bullets whistled overhead. With defeat in the air, “I perceived a charge,” Eaton decided, as his “only resort.” Although they were outnumbered, the men of the 441-mile trek across the North African desert would not be denied victory. The warships paused, allowing an opening for the Marines and their party. Lt O’Bannon seized the moment, charging across the open area into the battery.

“We rushed forward against a host of [enemy],” Eaton reported, “more than [10] to our one.” A well-aimed bullet struck Eaton’s wrist just as the charge began, instantly taking him out of the fight. The defenders of Derna held out, content to exchange fire with the American coalition behind their defensive walls and breastworks, even under the renewed fire of the three warships.

As O’Bannon approached, the defenders of the fort had to decide: engage in a deadly brawl with the attackers or flee to safety. The audacity of the Marines panicked the defenders, who chose flight. The defenders abandoned their position quickly, leaving behind their cannon fully primed and ready to fire one last salvo at the sprinting Marines. Mustafa’s men broke without firing the cannon, unwilling to face close combat with the Marines.

O’Bannon and his men leapt over the breastworks, surprised to find the battery abandoned by the fleeing enemy cannoneers. O’Bannon ripped down the sultan’s flag from the ramparts, replacing the enemy flag with that of the United States, announcing American victory. This was the first time the colors of the United States waved above a captured fort in the “old” world. The battle was not without cost. Marine Private John Wilton was killed in the assault, with Corporals David Thomas and Bernard O’Brian wounded. This left only four Marines still in the fight. Ten Greek soldiers were wounded in the charge, but the flag of the United States flying over the captured battery announced defeat for the Tripolitans.

The Marines promptly turned the guns on their previous owners, who were still not inclined to offer firm resistance to the Americans. The Tripolitans continued to fire from every palm tree and city wall in retreat, but sheltering in the houses proved disastrous as point blank shells from the American warships rooted out the Tripolitans one by one. Karamanli and his advisors captured the now-empty governor’s palace, but Mustafa eluded capture. He first found safety in a mosque, but then retired to the sacred sanctuary of a harem, where safety was more assured.

The battle lasted only two and a half hours, with gunfire ending at 4 p.m. The bashaw’s cavalry completed the victory by flanking the enemy’s retreat, ending the fight. Derna was now under complete American control, except for the sanctity of the governor’s harem. The conduct of Lieutenant O’Bannon and his Marines drew the admiration from all who witnessed the attack. Their bravery and leadership inspired the entire coalition force, as did the three Navy commanders who Eaton declared “could not have taken better positions for their vessels nor managed their fire with more skill and advantage.” The Hornet’s cannon fired so often their plank shears gave way, disabling the guns, which required a time in port for repair.

Eaton saved his finest words for Lieutenant O’Bannon, whose “conduct needs no encomium, and it is believed the disposition our Government has always displayed to encourage merit, will be extended to this intrepid, judicious and enterprising Officer.” Eaton also served as a recruiter for the Marine Corps in recommending Farquhar, who “has in all cases of difficulty, exhibited a firmness and attachment,” to the rank of lieutenant in the Marine Corps. No record exists of Farquhar serving in the Marine Corps.

The price of victory proved high for the six enlisted Marines in the battle. In addition to the loss of Private Wilton and Thomas and O’Brian’s injuries, Private Edward Stewart was badly wounded and eventually died on May 30, 1805, in Derna. Only Corporal Arthur Campbell and Private James Owen were uninjured.

Fighting continued on June 3, when the 16,000 soldiers from Tripoli, commanded by Commander in Chief Hussein Bey, finally reached Derna to drive Karamanli and the American coalition back to Egypt. Karamanli’s men held their own for a time but were driven back into the walls of the city. O’Bannon led his four Marines and other reinforcements through Derna to reinforce Karamanli. They were greeted by “every body, age and childhood, even women from their recluses, shout[ing], “Live the Americans, Long live our friends and protectors!”

The American warships opened fire with the ships’ guns and captured artillery, easily crushing the attack from the city walls. Lieutenant O’Bannon “was impatient to lead his Marines and Greeks, (about 30 in number),” to further disperse the attackers, who fled in great disorder, ending any thought of Bashaw Yusuf driving his brother out of Derna. Bey deserted his forces because of his defeat, fleeing to the desert to escape retribution for his failed leadership.

On April 29, Master Commandant Hull wrote to Commodore Barron from Derna, informing him, “I am clearly of the opinion that three or four hundred Christian soldiers, with additional supplies, will be necessary to pursue the expedition to Benghazi and Tripoli.” The way lay open to carry the war to the capital city, freeing the American prisoners and putting an end to the conflict. Instead of allowing Eaton and O’Bannon to march on Tripoli, Barron chose the now more certain path of diplomacy.

With the fall of Derna and repulse of his army, Yusuf ended hostilities with the United States. He sent a message to the Americans through the Spanish consul in Tripoli that the time had come for peace negotiations. By chance, Tobias Lear, the United States Consul General to the Barbary States, was visiting Barron at his headquarters on the island of Malta. Barron entrusted Lear to begin negotiations with Yusuf to end the war with Tripoli. A former secretary to George Washington, Lear proved a skilled diplomat as well, ready to take on his opponent to create a lasting peace.

On April 30, Lear noted the failure of previous negotiations “on the part of the Bashaw to make peace on admissible terms. Lately there seems to be a Change in his sentiments … a few weeks will decide the matter, by negotiation or try the effect of our cannon.” The USS Essex transported Lear to Tripoli on May 26, where he received a formal salute of nine cannons instead of the previously common seven, admitting the new prominence of the United States.

Bashaw Yusuf immediately threatened to kill all of the American prisoners if the march from Derna continued, but should his brother withdraw, the captives would be freed. This concession brought America to a quick treaty on June 3, 1805. The United States paid a $60,000 settlement, thereby liberating the 400 American prisoners in 24 hours, with an agreement protecting American trade with no further payment to Tripoli. Lear admitted Karamanli “was entitled to some consideration from us, but I found this impactable, and if persisted in would drive him to measures which might prove fatal to our countrymen in his power.”

On May 19, 1805, Commodore Barron wrote to Eaton, informing him that Karamanli “has not in himself energy or the talent, and is so destitute of means and resources, as not to be able to move on with successful progress … he must be held unworthy of further support … you will state explicitly to his excellency, that our supplies of money, arms, and provisions are at an end.”

Outraged, Eaton wrote directly to Secretary of the Navy expressing his view of the treaty and the denial of his request of 100 Marines to support the expedition. Barron “had not seen Tripoli during the last eight months,” he pointed out, “his squadron had never been displayed to the enemies’ view, nor a shot exchanged with the batteries of Tripoli since Commodore Preble [of earlier conflicts in the Barbary States] left the coast.”

In retrospect, Eaton still regretted that he had not been permitted a larger Marine Corps detachment at Bomba, “within an hour’s march of the main force of the enemy … only for the want of [200] bayonets! …In a bombardment or a cruise, Marines are of little more use in a man of war than cavalry or pioneers,” he wrote, “and while laying in port they are used only as badges of rank and machines of ceremony. Why not send them where they could be useful … Gentlemen of that corps, I am well assured, actuated, like their brethren of the navy, by a manly zeal to distinguish themselves, were ready to volunteer for the expedition. And it did not require a greater latitude of discretion to indulge to fight at Derna, than to furlough them on parties of pleasure at Catania. … Would such a detachment have defeated the great operation carrying on by the squadron?”

If Lieutenant O’Bannon and six Marines led the capture of Derna and repulse the soldiers sent to recapture the city, the presence of 100 Marines might well have overrun each coastal town before them, including the capital of Tripoli. Eaton also despaired at Lear’s payment of $60,000 for the release of prisoners while he held Derna, one of the most prosperous and largest cities under Yusuf’s rule, with a population between 12,000 to 15,000 citizens who could have been exchanged for the captive Americans.

Consul Lear’s final pronouncement over the embarrassment of Karamanli was direct and to the point. “This is all that could be done,” Lear wrote, “and I have no doubt the United States will, if deserving, place him in a situation as eligible as that in which he was found.” Hamet Karamanli never regained his rule over Tripoli and returned to his exile in Egypt, accompanied by Eaton. In exchange for his withdrawal, a provision of the treaty insured his wife and children, held hostage by Yusuf, were returned to him. Unfortunately, his Bedouin followers were rumored to be massacred by Yusuf’s forces, never to rise against the throne again.

The lessons of American power reverberated across North Africa, resulting in new peace agreements with Algeria and Tunis. “The Mediterranean was the cradle of the American navy,” wrote M.M. Noah, the former United States consul in Tripoli in 1804. “It’s character and discipline—subsequent success in war—its influence in peace, and its present high character throughout the world have their origin in the wars declared against the several powers on the Barbary coast.” The Marine detachments aboard those ships and on land at Derna earned the same honor “to secure forever to the American flag that freedom which it claimed.”

Lear did acknowledge Eaton and the Marine Corps’ accomplishments, closing his letter with praise, writing, “I pray you will accept yourself and present to Mr. O’Bannon and our countrymen with you, my sincere congratulations on an event which your and their heroic bravery has tendered to render so honorable to our country.” The deaths of Private Wilton and Stewart and the wounds of Corporals Thomas and O’Brian are evidence enough of the valor required to end the hostile relations between Tripoli and the United States.

On March 18, 1806, the Senate of the United States passed a resolution rewarding the surviving Marines, Lieutenant O’Bannon, Corporals Campbell, O’Brian and Thomas, and Private Owen, for their services in North Africa. O’Bannon and Midshipman George W. Mann each received a thousand acres of land in the territory that would become Kentucky, and “each of the four enlisted Marines awarded 320 acres, to be granted to them respectively, their heirs, and assigns forever.” Eaton was also rewarded with the establishment of a town 6 miles square in the new territory, to be named Derne.

Lieutenant O’Bannon and his six Marines became celebrated heroes for the young United States, establishing the nation’s admiration of the fighting spirit of the Marine Corps. The events of 1805 are remembered with every rendition of “The Marines’ Hymn” with the words, “To the shores of Tripoli.”

Author’s bio: Mike Miller has written five books and many articles about Marine Corps and Civil War history. A longtime Leatherneck contributor, he retired in 2016 after a 34-year career in the Marine Corps archival, museum and history programs. His latest book is “The 4th Marine Brigade at Belleau Wood and Soissons: History and Battlefield Guide.”