Pocket-Sized Storyboards

By: Sara W. BockPosted on September 7, 2022

Zippos Carried into Combat Were More than Just Cigarette Lighters

By Sara W. Bock

When he found himself on a second tour in the heavy jungles of Vietnam in 1969, Kenneth Moulton wasn’t sure that this time he’d be lucky enough to make it home alive. The young radio operator and forward observer, soon to pin on the rank of sergeant, decided to mark the promotion by purchasing a memento, which in those days could be found in the pocket of nearly every Marine serving in a combat zone: a Zippo lighter.

A seemingly utilitarian buy—Moulton chose a standard brass-cased lighter from a post exchange in Da Nang—became something more consequential when, while on R&R in Bangkok, Thailand, Moulton had both sides of the lighter engraved with custom text that told the story of his service and, upon closer examination, reflected his sentiments about the grim realities of war.

In addition to basic information such as his name, service number, and years in the Marine Corps, Moulton included a quote by Julius Caesar, “Vidi, Vici, Veni,” modified to take on a subtly more vulgar meaning, and most notably, a list of locations around the world with asterisks to mark the number of times he had visited each. Vietnam. Okinawa. Bangkok. Singapore. Wake Island. Mexico. At the bottom of the list was “CONUS,” a commonly used acronym for the continental U.S., but instead of an asterisk, it was followed by a question mark. Would he ever be stateside again?

In 2015, along with other items of significance from his service in Vietnam, Moulton donated the lighter to the National Museum of the Marine Corps, where it joined an extensive collection of lighters under the care of Cultural and Material History Curator Jennifer Castro, whose other collections range from sweetheart jewelry and movie posters to toys, watches and more. And while several of the lighters she’s accepted from donors were made by other brands, Zippos, known for their incomparable windproof design, have long been favored by Marines and other U.S. servicemembers.

Castro compares personalized Zippos of the Vietnam era to the challenge coins that are commonly purchased and exchanged by Marines today: a small token by which to document service with a unit, celebrate promotions and occasions or say “thank you” for a job well done. But beyond the challenge coin comparison, Castro considers them to be statement pieces, or as she likes to refer to them, “personal storyboards.”

“They document a distinct period of time in an individual Marine’s service,” Castro said. “And the common tradition among Marines, and I feel like most servicemembers, to buy something inexpensive, using it to tell their own story, their specific service during the war. […] They’re very unique and they’re representative of the individual Marine who obtained it and had it customized to talk about their service.”

When she accepted Moulton’s donation, Castro recalls him telling her that he had purchased lighters to document his promotions in rank and to help with his “pack a day” smoking habit. And while the engraving on his 1969 Zippo is one-of-a-kind, it is just one of countless personalized lighters carried by Marines and other American servicemembers during that era.

There’s another Vietnam-era Zippo lighter in the museum’s collection that appears completely unremarkable. There isn’t anything “personalized” about it at all, but in her collection file, Castro notes: “the silver tone Zippo flip-top lighter has a tiny knob of broken metal on one side where an emblem or insignia has fallen off.”

The lighter, owned by Marine veteran Harold Ligon, once bore a brass Marine Corps emblem—the iconic eagle, globe and anchor—on its case. While serving with Company A, 1st Battalion, 26th Marine Regiment in Vietnam in 1967, Ligon developed a nervous habit. He would reach into his pocket and rub the insignia in an attempt to ease his stress and anxiety. Eventually, the eagle, globe and anchor was completely worn away, leaving behind only a very small bump and a faint outline of where it once had been adhered.

“It was his worry stone,” Castro said of the Zippo, which Ligon carried with him during periods of intense combat, including at Hill 881 South. She found his story to be particularly profound. “The best ones that come in are the ones that come with the history of the Marine who served,” she said.

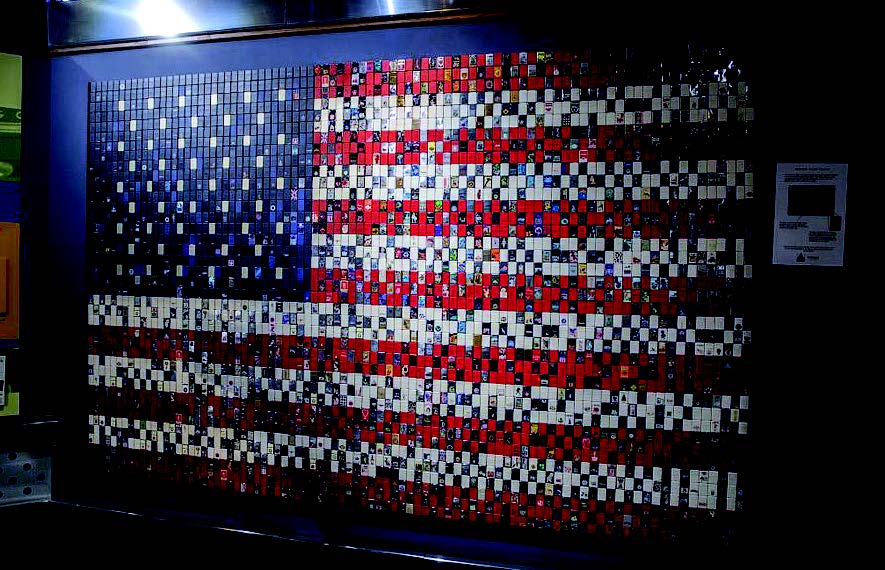

Among the museum’s most interest-ing Zippo lighters, most of which are not currently on display but rather are stored in a nearby auxiliary facility, a broad range of attitudes and narratives are conveyed.

Once owned by Private First Class Gary Morrison, one Zippo portrays Snoopy as a flying ace, sitting on his shrapnel-ridden dog house under a speech bubble that reads “F— It” on one side, and an image of Snoopy with his head hung low, with a thought bubble that says “Sex” on the other. Charles Schulz’s “Peanuts” cartoons had been a regular feature in Stars and Stripes, Castro says, and were popular among the troops, many of whom identified with the fictional beagle’s various woes. Yet another lighter, donated by retired Marine Lieutenant Colonel Larry Britton, a CH-46 pilot who served with HMM-364, “the Purple Foxes” in Vietnam, was a gift from his brother that displayed the crest of Britton’s college fraternity, Delta Sigma Phi. On the other side, Britton had the following quote inscribed while still in Vietnam: “For those who fight for it, freedom has a flavor the protected will never know.”

Yet another was discovered by museum employees during the restoration of an Ontos vehicle in 2004, lodged in the front engine compartment. It was traced back to PFC Ralph Ronald Cummings, a Marine rifleman who was killed in action in Quang Nam Province, Vietnam, in 1970.

“Interestingly, PFC Cummings was not a crew member or related in any way to work with Ontos vehicles,” said Castro. “In discussions with veterans and curatorial researchers, it is believed that the piece fell inside the vehicle engine from Cummings’ uniform pocket. Interviews with Ontos veterans revealed that Marine casualties were often evacuated from the battlefield by being thrown across the sloped front of the vehicle. It is possible that PFC Cummings was wounded or killed and placed on the sloped front of the Ontos vehicle, and the lighter slipped from his pocket and into the engine compartment.”

The engraving on the lighter reads “Cummings,” and in Vietnamese, “LINDA Nguoi yeu ly tuong cua RON,” which Castro says roughly translates to “Linda, Ron’s lover.” To date, Castro has been unable to track down his next of kin or anyone connected to him by the name of Linda.

“From a cultural perspective, the lighters demonstrate sort of the pride, the flair, the esprit de corps of U.S. Marines serving overseas,” said Castro. “During the Vietnam War, engravings found on lighters documented the experiences of men at a certain place and time, capturing both a wide range of sentiments and opinions about the war and individual experiences.”

But the tradition of Marines carrying Zippos into combat began long before the U.S. entered the war in Vietnam. The lighter was first envisioned by George G. Blaisdell in Bradford, Pa., in the early 1930s when, while sitting with a friend at the Bradford Country Club, Blaisdell watched him fumble with an Austrian lighter that required him to use two hands to light. He began to reimagine the lighter, which worked well in windy conditions, working to craft a new and improved version that was both attractive and could be operated with ease using only one hand. The first Zippo was produced in 1933, and Blaisdell’s patent application was approved in 1936. They sold for $1.95 and came backed by a lifetime guarantee, which the company—now owned by Blaisdell’s grandson, George B. Duke—continues to issue today for its products, which are still crafted in Pennsylvania. Remarkably, despite a steep decline in cigarette smoking in recent decades, 2021 marked the best sales year in the company’s history, proof of the enduring longevity of the brand.

During World War II, the lighters were so popular among servicemembers that from 1943 to the end of the war, Zippo allocated its entire production to the armed forces, making them available for purchase only by members of the U.S. military, said Katie Zapel, Ph.D., the archives manager for the Zippo Manufacturing Company.

During WW II, said Zapel, Blaisdell “sent lighters to top military officials and the famous war correspondent, Ernie Pyle, who corresponded with Blaisdell. Blaisdell would send Pyle small shipments of lighters to give out to soldiers he met at the front. Pyle wrote back to Blaisdell, calling Zippo lighters ‘the most coveted item on the battlefield.’ ”

“Amid the uncertainty of war, there was one thing a [servicemember] could rely on—his Zippo lighter. In rain, wind or snow, it worked every time,” said Zapel. “The company archives are filled with letters detailing the services a Zippo lighter was called to perform: heating rations in a helmet, lighting campfires, sparking fuses for explosives, hammering nails and even signaling […] with the famous Zippo ‘click.’ On several occasions, a Zippo lighter in a shirt or pants pocket even saved a life by deflecting bullets.”

Zapel references a 1946 newspaper article in which Marine Colonel Bob Churley said that a Zippo lighter likely saved his life.

“Churley, a U.S. Marine serving in North China/Manchuria, was helping to hold back [Mao Tse-tung’s] Chinese communist army from overtaking the region until Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Chinese forces could arrive,” said Zapel. “Churley’s plane experienced a frozen carburetor and landed in communist territory. The pilot, a second lieutenant, pulled out his Zippo lighter, lit it and held it against the carburetor. It worked and they were able to fly off.”

Because of a brass shortage during WW II and subsequent rationing, Zippo began making its cases from steel instead of the standard brass. To prevent corrosion, the steel cases were dipped in black paint and then baked, producing what became known as the Black Crackle® finish. According to “Warman’s Field Guide: Zippo Lighters” by Dana and Robin Baumgartner, a similar shortage during the Korean War necessitated another temporary return to steel cases. In the mid-1950s, the company began stamping date codes on the bottom of each lighter, which now help collectors and historians like Castro date and identify them.

“They became big during World War II, but in a different way, they became such a cultural item by the Vietnam War. They were used to heat food, signal helos at night during rescue missions, and more,” said Castro. “It was reported during the time that Marines used them to set Vietnamese village huts afire while on search and destroy missions. Zippos were reportedly used so often in the country on search and destroy missions that the GIs nicknamed them ‘Zippo Missions’ or ‘Zippo Raids.’ Zippo became synonymous with flame-thrower and was used as a verb in the phrase, ‘Zippo that hut,’” she added.

For Castro, small items like Zippo lighters that might seem trivial often carry a great deal of significance and might be exactly the kind of donation the museum may be looking for to fill gaps in its collections.

“The museum collects all the things that people think we do,” Castro said. “They’ll call us up and say, ‘Hey, I have uniforms, I have weapons […] but they don’t always necessarily think of the things that might tell the Marine’s individual story. There are so many more things that the museum accepts than what people normally come to us with.’ ”

To Castro, it’s significant that Zippos were an item that nearly every Marine chose to carry in their packs, their pockets or their helmet straps—and it’s a testament not only to the multitude of uses for the lighter, but also to the sentimental and personal value attached to them.

“How much stuff can they actually carry with them during combat? This was something they felt was worth carrying,” Castro said.

Author’s note: Special thanks to Jennifer Castro, the cultural and material history curator at the National Museum of the Marine Corps, for significant contributions to this article.

Editor’s note: All lighters from the collection of the National Museum of the Marine Corps were photographed by Jason Monroe.