Dec. 7, 1941…Standing Duty as the Japanese Attacked

By: Ray ElliottPosted on December 4, 2024

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the December 2016 issue of Leatherneck Magazine. It is being re-published in remembrance of the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Sergeant Delmar “Dick” Lewis was exhausted. Having recently returned to Hawaii after being sent to build airstrips on the islands in the Central Pacific, he was preparing to relieve the guard who was on duty at Ford Island a few minutes before 8 a.m. on Dec. 7, 1941.

“Four of us were standing there at the end of the runway,” Lewis recalled in a later interview, “and I looked over my shoulder and saw these planes flying right at us. I thought they were Army planes at first and wondered why they were flying maneuvers on Sunday morning,” Lewis said.

“Then I noticed … meatballs on the wings and wondered why they covered up the stars on the bottom of the wings. That’s how dumb I was at first. Then I saw something coming out of the planes and didn’t know what it was that was hitting the airstrip and making fire jump off the runway. ‘That looks funny,’ I said. ‘They’re throwing something that’s landing on the ground out there.’

“They were still quite a ways away from us, and pretty soon something went, ‘Yiiinnnggg,’ and I went end over end. I got a ricocheted bullet in my right shoulder. And I knew it was for real then.”

Bleeding badly, Lewis yanked off his dungaree jacket to get down to his undershirt, which he tore off. He used his fingers to push the shirt into the hole in his shoulder to stop the bleeding. But his arm was hanging straight down and he couldn’t move it.

“We’re under attack, boys,” Lewis shouted, watching the Japanese airplanes fly over the island. “This is the real thing.”

By that time the smoke was beginning to billow up over the harbor. Lewis said they were on the other end of Ford Island, about 3 miles from Battleship Row, and smoke was billowing up over the hangars, too. Aircraft were folded up and burning right in front of them.

“There was a big stack of empty, 50-gallon oil drums out there, not far from where we were standing, and I think the plane that did get me was after [the] drums, thinking they were probably full of gasoline. They were shot full of holes and nothing happened, and he didn’t waste any more rounds,” said Lewis.

Lewis said he tried to find a corpsman.

“I was walking,” he said, “and I was better off than a lot of others and didn’t find one who wasn’t busy.”

Since he couldn’t get medical attention, Lewis and the three other Marines tried to get a boat back to Marine Corps Air Station Ewa at Barbers Point, where they previously had been stationed and had built an airstrip before going to the Central Pacific.

According to Lewis, the four of them couldn’t find a boat, so they volunteered to help remove the dead and wounded in Pearl Harbor. Later, when they finally got near Ewa, they were able to go ashore and found that it had been hit hard.

“They destroyed about every … plane at Ewa,” Lewis said. “We were an army without anything to fight with. I only had a .45, and you can’t shoot planes with a .45.”

Lewis received medical attention on the base, but went back to duty after the wound was dressed and bandaged. “I don’t need to be in the hospital,” Lewis told the medical personnel.

Like many men who joined the military during the Great Depression, Lewis had traveled around the country looking for work. Originally from Illinois, he spent the majority of his life farming, but went to Chicago in November 1939.

“I’d hitchhiked around 25 states looking for work. I’d hear of a job somewhere and take off for it but never found much. I finally got tired of it in Chicago and joined the Marine Corps.”

Assigned to the Marine air wing in San Diego, Lewis met pilot Loren “Doc” Everton and served with him through the first years in the Pacific in what became Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 212. They served together again during a second tour in the Pacific from September 1943 to November 1944, when Everton took command of VMF-113. Everton was awarded the Navy Cross and a Distinguished Flying Cross for his service.

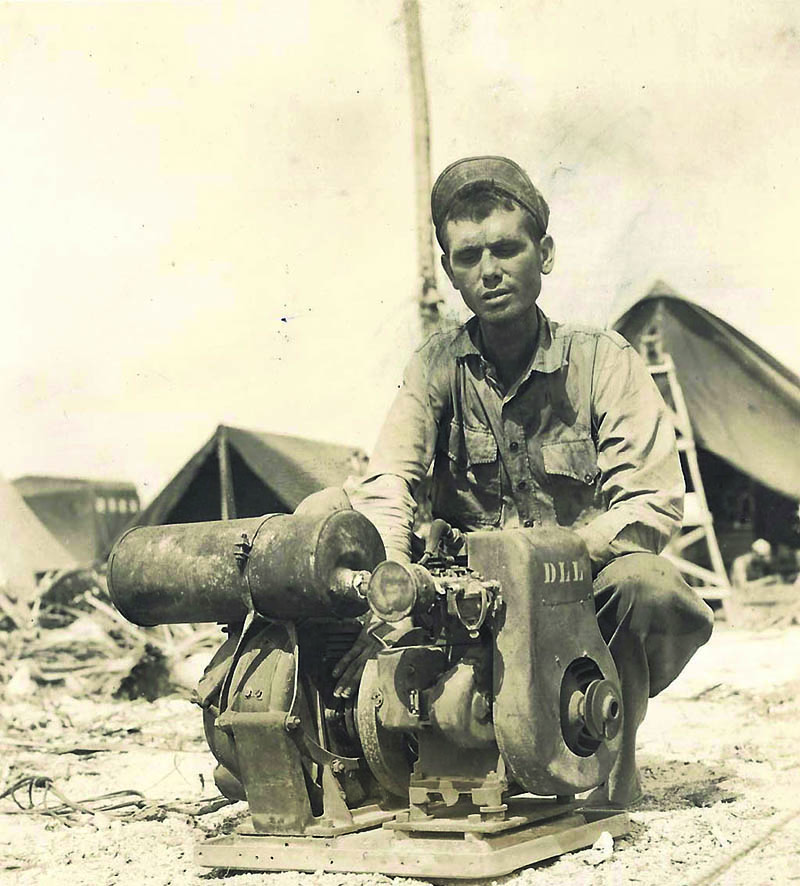

In VMF-113 pilot Andrew Jones’ book, “The Corsair Years,” he writes: “Doc Everton’s devotion to his people paid off not only in up-and-down loyalty, but in horizontal lockstep at every level. It was much in evidence among the salty non-coms he’d hand-picked for enlisted leadership—Sully and John Cates, Delmar Lewis and Nick Sheppard, George Duffy, Abie Greenhouse, Jack Carol, Al Ackerman, Fred Scroggins and my plane captain, Joe Gonzales, to name a few. Some of them had served with him before Pearl Harbor. They called themselves ‘the airfield builders’ for they had prepared the airstrips and built facilities at Ewa, Espiritu Santos, Efate, Guadalcanal and here on Engebi, and they had let it be known throughout the organization that they would lay a strip down the mainstream of hell if Doc asked them to.”

In early 1941, the forward echelon was sent to Ewa to build an airfield at Barbers Point.

“When we first went out there, we called it Ewa Mooring Mast,” Lewis said. “You won’t find many people that know that, but there was a big old mooring mast out there. They were looking around to see how it would be to have those big dirigibles haul people from the States out there. Of course that didn’t work out, but this mooring mast was a place they could land in. And around that we build an airstrip.”

From there, they went to Guam and other islands building airstrips in preparation for the war Lewis said they felt was coming. “… We went on to Midway and helped build an airstrip on Eastern Island and got on ship and came back to Ewa on the fourth or fifth of December. And we came into Pearl Harbor and unloaded all our planes and things,” said Lewis.

“And for some reason, right then they took a number of ships out. Now I’m not talking about battleships. I’m talking about troop transport ships like I was on. [They took them] out in the ocean so these bigger ships, the battleships, could come in. Lots of our material went back out. We hadn’t gotten it all unloaded yet—and I was down at Ford Island, which is right in the middle of Pearl Harbor. I was sergeant of the guard, and I was off at 8 o’clock that morning. I’d gone out to relieve the old guard and put the new guard on.”

The enemy aircraft flew over the mountain range to the north, over Schofield Barracks, and came right in over Barbers Point, Lewis said. Another group came down the middle over the bay and Aiea Heights.

“They never did realize they were flying over the tank farm on the other side of Aiea Heights where there was 50-75 30,000-barrel tanks with tanker oil for the ships. They never strafed or bombed that area,” Lewis said.

“We couldn’t get off the island; other guys wanting to get on couldn’t get on. I saw them bring in Navy men. Well, they could have been Navy or Marines. They were bringing them off the ships. They brought them in in front of that administration building, which was probably a block long. It had a big arched drive in front of it and a sidewalk in front of it and a piece of grass between the sidewalk and the building. They brought them in there, [they were] covered in tar and oil, dead, and I saw a stack of men there when I went around trying to find a doctor to do something for me,” said Lewis.

“For the full length of that administration building, which I’m going say was 200 feet, there were bodies stacked up four and five high like cord wood,” Lewis said, because when the men were pulled out of the water, there wasn’t anything that could be done to save them.

The men had been blown off the ships out into the oil-covered harbor.

“Most of it was burning and they jumped in it, then they had to come back up through it and come right back up in the fire. They had oil all over them and they couldn’t see anything over their head and face. And a lot of [men burned] to death right there … . That night, after that hectic day, wherever you were, it was a good idea to stay there or you could get shot. You could hear machine-gun and rifle fire all night. Everybody was gun happy that night.”

Within a month after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Lewis said, volunteers were asked to man the forward echelon “going south.” They didn’t know where there were going, but they thought they were going right into battle.

“They sent us to Johnston Island and we built an airstrip, then we went to Palmyra [Atoll] and we built an airstrip and went on down to the Hebrides Island.”

Lewis spent more than six years in the Marine Corps, including two different tours in the Pacific. He was discharged on Dec. 7, 1945, exactly four years after he was first wounded while relieving the guard on Ford Island on the morning of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

“What I saw there … is still very, very vivid in my mind,” he said in an interview a few years before his death in 2005. “They killed more than 2,000 men [2,403 killed and 1,178 wounded] and destroyed our battleships and planes. I couldn’t believe we let them drive up to our back door and shoot us. But that’s exactly what they did.”

Author’s bio: Marine veteran Ray Elliott is an English and journalism educator who has written three novels and edited numerous others. He was communications director of the Iwo Jima Association of America and Black Sands editor, and currently edits The Spearhead News for the Fifth Marine Division Association and serves as its secretary. The three-time president of the James Jones Literary Society, he worked as the military adviser in London on the 2013 production of “From Here to Eternity—the Musical.”