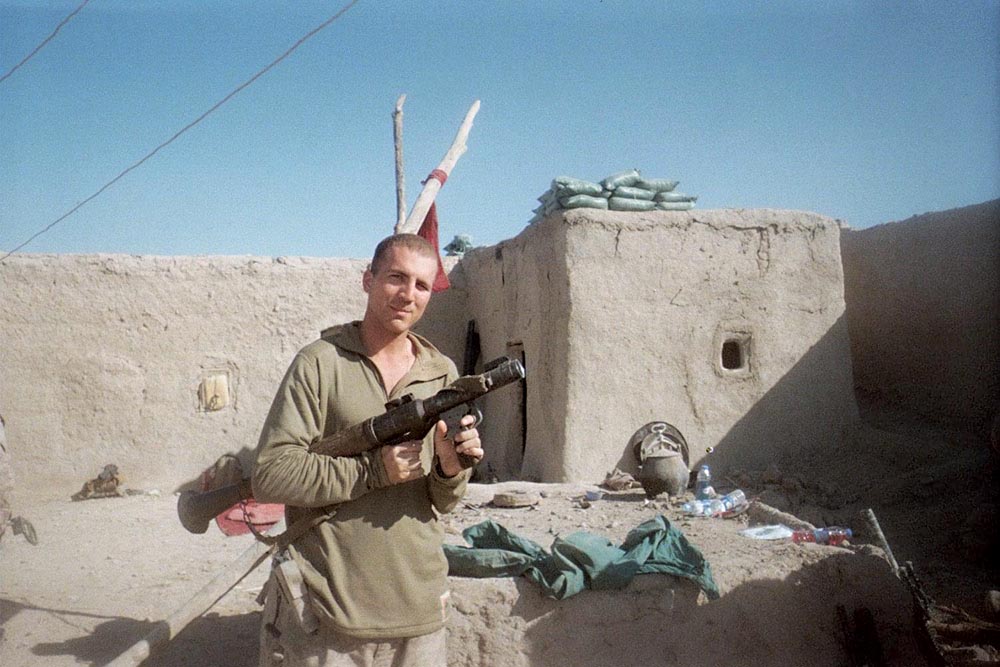

Capt Jeremy Nelson fires the Beretta M9 during a weapons marksmanship course at Camp Leatherneck, Afghanistan, Oct. 4, 2013. (Photo by Sgt Bobby J. Yarbrough, USMC)Carried by many but seldom fired at the enemy, handguns fill a somewhat strange niche in the Marine Corps’ arsenal. Because they are mainly issued to personnel who are not expected to need them, their importance is often overlooked; those who carry handguns, however, rely on them as a weapon of last resort in case all else should fail. As it is finally replaced by the M17 and M18 Modular Handgun System (MHS) after 32 years in U.S. military service, the Beretta M9 leaves behind a mixed legacy. Those who trained on it alternately praise and criticize the pistol’s attributes. Depending on who’s talking, the M9 is either one of the finest service pistols of its time or an inherently flawed design totally unsuited for military use. To uncover the truth behind these claims, one must understand the history behind them. The story of the Beretta M9 is a complicated one, poorly documented and fraught with political scandal, public controversy, and inter-service rivalry from the very beginning.

Marines who favor the classic M1911A1 over the M9 platform will rejoice to know that they can blame the Army and Air Force for causing the beloved .45 to be replaced. When the Air Force became an independent branch of the U.S. Armed Forces, it took with it whatever small arms it had in inventory as part of the Army. As the service rapidly expanded through the 1950s and ’60s, its security forces needed to expand their arsenal. Because the last M1911A1s were manufactured in 1945 and the Department of Defense would not authorize further orders, the Air Force had instead relied on the smaller and lighter .38-caliber M15 revolver to arm its security forces since at least the early 1960s. Beginning in the 1970s, however, the Air Force began to encounter problems, mainly squib loads, with their M41 ball service ammunition. Each time a defective round created a catastrophic failure, the entire lot of ammunition had to be marked as unsafe and removed from stockpiles; the Air Force found itself facing a shortage of .38 Special ammunition its airmen could trust to function.

The pistols were run through a battery of tests from 1977 to 1980, analyzing their performance in everything from accuracy and ergonomics to reliability in extreme conditions. Most of the pistols suffered from frequent malfunctions or parts breakage, with some even having their front sights fall out on the range. Only two designs survived to the end: the Smith & Wesson 459 and the Beretta 92SB-1. Military small arms requirements quote reliability in “mean rounds between failure” (MRBF), calculated by simply dividing the number of rounds fired by the number of any type of stoppages experienced. The Beretta proved to be the most reliable of the bunch; whereas the original requirements demanded at least 625 MRBF, it achieved a whopping 2,000. Furthermore, it proved to be easier to shoot accurately than either the M1911A1 or the M15, especially for less experienced shooters. Declaring the Italian pistol as the winner, the Air Force concluded its testing and prepared to sign a contract for 100,000 pistols in early 1982.

Before that could happen, however, the Army raised a complaint on the basis that the testing had not been sufficiently scientifically rigorous. They specifically cited the mud and extreme temperature testing as not replicable and complained that the M1911A1s in the control group were issued weapons and not factory-new examples procured specifically for the trials. Furthermore, because the Army uses more handguns than any other branch of the U.S. military and has its own very robust procurement system, they insisted that the responsibility to adopt the new service handgun should fall on them. Army Ordnance leadership discarded the AFAL’s results entirely and decided to conduct their own testing to select a new pistol, now dubbed “XM9.”

The Army issued a set of requirements in 1981 and received samples from four manufacturers but terminated the program the next February on the basis that none of the pistols met their requirements. Allegedly, none of them achieved any more than 600 MRBF. Due to increased scrutiny from Congress and the media, the Army withheld as much information as possible; to this day, very little is known about the 1981 trials. The original requirements and results are either not publicly available or have been lost to time. It is possible that the testing was manipulated so as to defeat foreign manufacturers’ designs or even sabotage the XM9 program as a whole in favor of keeping the M1911 in service. It is known that the Army was interested in the possibility of converting its existing pistols to 9 mm for NATO standardization instead of buying a new design, and that a significant contingent in the military and in Congress supported this idea. Whatever the case may be, widespread accusations of fraud convinced the Army to discard the results of its own “secret” trials and start over from scratch.

A total of eight manufacturers chose to compete; Beretta and Smith & Wesson both submitted virtually the same pistols they had sent to the AFAL trials. Famed German gunmakers Hecker & Koch and Carl Walther Waffenfabrik put forth their P7M13 and P88, respectively, and Steyr-Daimler-Puch out of Austria sent the model GB. Back from the AFAL trials were the Colt SSP and FN BDA despite their previous lackluster performance. Swiss company SIG had recently formed a conglomerate with a factory in Germany and offices in the United States; they submitted the P226, a derivative of their own highly innovative P220.

The Steyr GB was the first to fall, eliminated in May of 1984 for failing in reliability testing. It was an innovative and well-made pistol from Austria but never achieved success in the military, law enforcement, or civilian markets. Fabrique Nationale voluntarily withdrew its BDA soon after—not a debilitating loss, as they already held contracts for the M2 and M240 machine guns and would soon get one for the M249. Colt had suffered from issues with its SSP for years and unceremoniously withdrew the weapon in June; it would never see a full production run. Testing continued through the summer and was nearly finished by September. That month saw the rejection of the Walther P88, HK P7M13, and Smith & Wesson Model 459M, each for multiple reasons.

That left just two models still standing to compete head-to-head in the final phase of testing: the SIG Sauer P226 and Beretta’s current model, the 92F. Both achieved excellent reliability, 2,877 and 1,750 MRBF respectively, with a large advantage to the latter in dry conditions. Both pistols passed with flying colors and were deemed technically acceptable. Preference would be given to whichever manufacturer offered a better price on the total system package, including a set list of replacement parts, not just the unit price for the pistols. Bidding was aggressive, but Beretta gave the government a better deal. On Feb. 14, 1985, the U.S. Army officially adopted the Beretta 92F as the M9 pistol.

Despite the Army coming to the same conclusion as the Air Force had years before, the service pistol controversy only intensified. As soon as the Army made its announcement, competing manufacturers raised legal challenges to the decision. While the Army began purchasing shiny new M9s, the other manufacturers went to court, and the General Accounting Office launched an investigation into their allegations.

Smith & Wesson argued that the rejection of their 459 for failing firing pin energy and service life requirements had been unfair. In the interest of guaranteeing reliable ignition with the hard primers found on some military ammunition, the pistols were expected to meet NATO standards for the kinetic energy of the firing pin on impact. In converting from metric to U.S. imperial units, however, the Army had rounded their numbers up enough that the Smith & Wesson pistols were no longer deemed acceptable. Regarding service life, the published requirement was for the pistol to survive 5,000 rounds on average. In testing, the Army treated this as a minimum requirement rather than an average and rejected the 459M in part because one example out of three began to suffer cracks in its frame between 4,500 and 5,000 rounds.

SIG Sauer, represented in the United States by SACO Defense, complained that the pricing model the Army had used to make its decision was unfair. The Army’s solicitation required four magazines per pistol and one full set of spare parts for every 10 pistols. Beretta’s significantly lower prices played into their pistol’s selection as the M9, but SACO’s legal challenge suggested that their P226 required fewer replacement parts than the Beretta 92F and alleged that the listed spare parts had been counted incorrectly.

Part of the GAO’s investigation into the recently concluded pistol trials sought to address accusations of outright corruption. According to some people, the U.S. government had made a secret deal with the Italian government to adopt Beretta pistols for the military and the entire trials process had been a cover operation. According to others, the Army had conducted some of its testing in secret and leaked other competitors’ pricing data to Beretta to give them a competitive edge in the final bidding.

In the world of government contracts and especially military acquisitions, many safeguards exist to ensure free and fair competition. Unfortunately, bad actors can abuse those same legal mechanisms to waste taxpayer money by filing protests they know will not hold up in court. None of the legal challenges regarding the XM9 trials were deemed to have sufficient merit and were promptly thrown out, but the GAO continued to investigate at Congress’ behest until every allegation had been put to rest. The GAO’s independent investigation found no evidence of corruption or conspiracy surrounding the XM9 program and noted that SACO’s claims about spare parts were inaccurate at best, disingenuous at worst. They did find that Smith & Wesson had been eliminated unfairly; to put the whole matter to rest, the Army agreed to test the Smith & Wesson pistols again. After the manufacturer declined to participate, the final obstacles to full adoption of the M9 seemed to be gone.

Marines who served during the late 1980s will remember another controversy surrounding the M9 which arose soon after it entered service. Some pistols in Army and Navy service began suffering from excessive wear; frames developed cracks and a few slides even broke in half and caused minor injuries. The spectacular slide failures prompted an immediate response: until the problem was identified and solved, pistols were to be thoroughly inspected and have their slides replaced every 1,000 rounds. The government publicly accused Beretta of shoddy manufacturing and demanded they redesign the M9 to rectify the issue as soon as possible, lest the whole $75 million contract be thrown out. Such accusations dealt significant damage to the reputation of the pistol and the company itself.

By that time, the Beretta 92 had been in production for well over a decade with no such problems surfacing until now, so the company quickly recalled the failed slides to its factory in Italy to find out what was going wrong. The slides had already passed high-pressure proof testing and magnetic particle inspection when they were made, and metallurgical analysis showed that they had indeed been made to the proper specification. What Beretta found was that the slides had failed due to repeated firing with overpressure ammunition far outside the NATO specification, which would also account for the cracked frames.

The U.S. government then turned its attention to the ammunition manufacturers. Olin Winchester and Federal Cartridge Corporation had been awarded contracts to produce NATO-compliant M882 ball ammunition for the M9, but without any history of manufacturing NATO ammunition, Olin Winchester simply took civilian load data and reused it for military production. NATO cartridge cases, however, are not the same as civilian ones—while visually indistinguishable, the smaller internal volume meant that the same charge of gunpowder would produce much greater pressures. The result of the ammunition manufacturer not taking the time to recalculate its powder charge was that the pistols were subjected to mechanical stresses far greater than what they had been designed or built to handle. Given such defective ammunition, the real surprise is not that the pistols failed, but that it took multiple years for that to happen. Even after the problem was fixed, USSOCOM was still wary of the M9 and opted to purchase P226s instead, type designated MK25 Mod 0.

Understandably upset that the U.S. government had so publicly denigrated their pistol over failures caused by faulty ammunition, Beretta filed suit for defamation and won. Furthermore, the design changes and modifications to existing pistols were done at the government’s expense. All military M9s and civilian Beretta 92s produced since 1988 have a hammer pin with an enlarged end and a corresponding groove inside the slide. With this modification, even if early, defective Winchester M882 ammunition is used, it will physically block the slide from traveling far enough back to exit the frame. The civilian model’s designation was changed from 92F to 92FS to reflect this change; the same pistol is still in production and available on the civilian market to this day.

Ever since the technical data package was updated to reflect those safety modifications, every M9 pistol purchased by the U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Force has been identical. Apart from serial numbers and other manufacturer markings, any M9 part made in the late 1980s should be identical to the corresponding part made in the 2010s. On the civilian side, however, Beretta continued to refine and update the design throughout the next several decades. The beginning of the Global War on Terror sent thousands of M9s into combat for prolonged periods, and with that trial by fire, Marines began to recognize some of the pistol’s shortcomings. In 2003, the Marine Corps expressed interest in certain improvements made to civilian variants of the pistol but that were not available to the military. Because the Marine Corps lacks the same kind of resources and acquisitions system the Army has, it was not allowed to bring new M9s into the inventory that did not comply with the old specifications from the 1980s. It could, however, use its discretionary powers to purchase new pistols in a commercial off-the-shelf configuration (COTS) with the features they desired.

Marines have carried pistols from the M9 family from Operation Just Cause to the war in Afghanistan and every deployment in between. The weapon has served the Marine Corps for more than three decades and on six continents. While fired relatively little in combat, the M9 saw extensive use among Marines in more specialized roles, such as MPs and Personal Security Details. It was also relied upon by some machine gunners and radio operators, among others, as a last line of defense against enemy combatants should all else fail.

Throughout its service history, the M9 garnered a controversial reputation. Some hailed it as a highly accurate and reliable handgun, while others complained about its perceived lack of lethality. It is usually compared to its long-lived predecessor, the iconic and heavily romanticized M1911. “Every time you get rid of some weapon, there is a lot of nostalgia,” said Colonel Tim Mundy, a retired Marine infantry officer. “People always act like the sky is falling.”

Some older Marines initially viewed the M9—a new Italian pistol firing a smaller German round—with some skepticism, but according to Mundy, whose assignments included a tour as commanding officer of the School of Infantry-East, “A few would admit that the 1911s were loose, inaccurate, and worn down.” Despite the older pistol’s legendary reputation, it was clearly antiquated and most of the examples in inventory had long outlived their usefulness. Colonel Chris Woodbridge, USMC (Ret), who also served as an infantry officer, agreed with that assessment. “You’d still see them [M1911s] in the armory in the late 1980s,” he recalled. “They were like maracas, they were so loose. The parts were so worn that they were really loose-fitting and consequently they could be unsafe.” Mundy and Woodbridge, both of whom commanded infantry Marines in combat, said that the new pistols were a welcome replacement.

Although the M9 proved easier to shoot than its predecessor, some safety problems sprung up as a result of user error. Marines in combat arms military occupational specialties, such as gunners and mortarmen, had ample opportunity to train with the pistol, but many staff officers and senior NCOs usually only fired their service weapons once a year for qualification. Good safety habits, therefore, weren’t always retained. As requested by the military and produced by Beretta, the M9 by itself is an exceptionally safe pistol, with multiple mechanical interlocks to prevent it from firing unless the trigger is physically pulled all the way to the rear with the external safety disengaged. No mechanical safety, however, can completely prevent accidents that arise from mishandling. Negligent discharges occasionally occurred at the clearing barrel when a Marine pulled the trigger without clearing the pistol properly. Mundy and Woodbridge both said that this was mostly a problem early on in the M9’s service history, particularly in the summer of 1990 during the large mobilization at the outset of Operation Desert Shield. Marine Corps leadership decreased the spate of negligent discharges by increasing safety training and punishing those who caused them.

As for reliability in combat environments, opinions on the M9 differ. In retired Major Vic Ruble’s experience, it was “totally luck of the draw who gets what,” adding that some of the pistols worked well, while others did not. The poor reliability was primarily due to lack of maintenance, according to those with firsthand experience, including Ruble, who made numerous combat deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. The Beretta 92 series was already a mature and refined service pistol by the time the U.S. military adopted it; the Marines interviewed for this article all said that while no firearm is perfectly reliable, the M9 typically ran well when properly maintained. During the Global War on Terror, however, M9s in service began to suffer from serious mechanical problems and even parts breakage issues. Small arms expert Christopher R. Bartocci worked as a consultant for the Department of Defense investigating failures in service weapons during that time; he noted that every broken part that he found had either not been replaced at the proper time or had been manufactured incorrectly to begin with. He determined that armorers had either not been trained properly on the required maintenance and parts replacement schedules or were simply not paying enough attention to notice signs of excessive wear in critical areas. The M9’s recoil spring and locking block are two of the most critical components to replace with expected service lives of approximately 5,000 and 10,000 rounds, respectively. If either of these components are not replaced on time, the pistol will begin to malfunction and will eventually jam up completely when the locking block breaks.

In recent years, M9 and M9A1 pistols in U.S. military service have begun to show their age. Decades spent in harsh conditions combined with poor maintenance and infrequent parts replacement have taken their toll, and advances in technology have made the core design appear relatively dated. While the military originally sought out the Beretta 92 for its double-action/single-action trigger system in the interest of safety, modern striker-fired pistols offer a more consistent trigger pull and less complex control scheme. The M9’s aluminum alloy frame made it relatively lightweight for its time but relatively heavy compared to modern polymer-framed pistols. Due to these and other reasons, every branch of the military has moved toward the new M17 and M18 pistols, which began to replace M9s and M9A1s in 2017; the last of the legacy pistols have already left Marine Corps service.

Between its introduction in the 1980s and its replacement in recent years, the M9 was fielded in large numbers and served the Marine Corps in conflict zones all over the world. Ruble said he is still glad he carried it in Iraq and Afghanistan as it demonstrated its value on several occasions. Inside buildings and vehicles too cramped for the M16 to be useful, he took advantage of the M9’s greater maneuverability.

Even beyond its utility in combat, it was a valuable tool for self-defense and deterrence. Handguns are still seen as a status symbol in many parts of the world. As chance would have it, officials in Saddam Hussein’s government had favored older Beretta designs before the invasion; the Italian pistol’s familiar lines made a significant impression on locals who saw it. “A pistol was a big deal, so you needed to know that going in,” Ruble recalled. “If you pull it, they expect you to use it, and they’re … terrified of that.” Over in Afghanistan, with the preponderance of green-on-blue attacks, Ruble said he depended on his pistol even more when working with the Afghan military and police.

Even when he and other Marines didn’t know if they could trust the locals, they trusted the pistol as a symbol of authority, a deterrent, and a last line of defense. In that respect, though held back by lack of maintenance, the M9 served the Marine Corps admirably for more than three decades in every clime and place.

Author’s note: The author would like to give special thanks to Christopher R. Bartocci and David J. Schneider.

Author’s bio: Sam Lichtman is a freelance writer who specializes in small-arms technology and military history. He has a weekly segment on Gun Owners Radio. He is a licensed pilot who lives in Virginia.