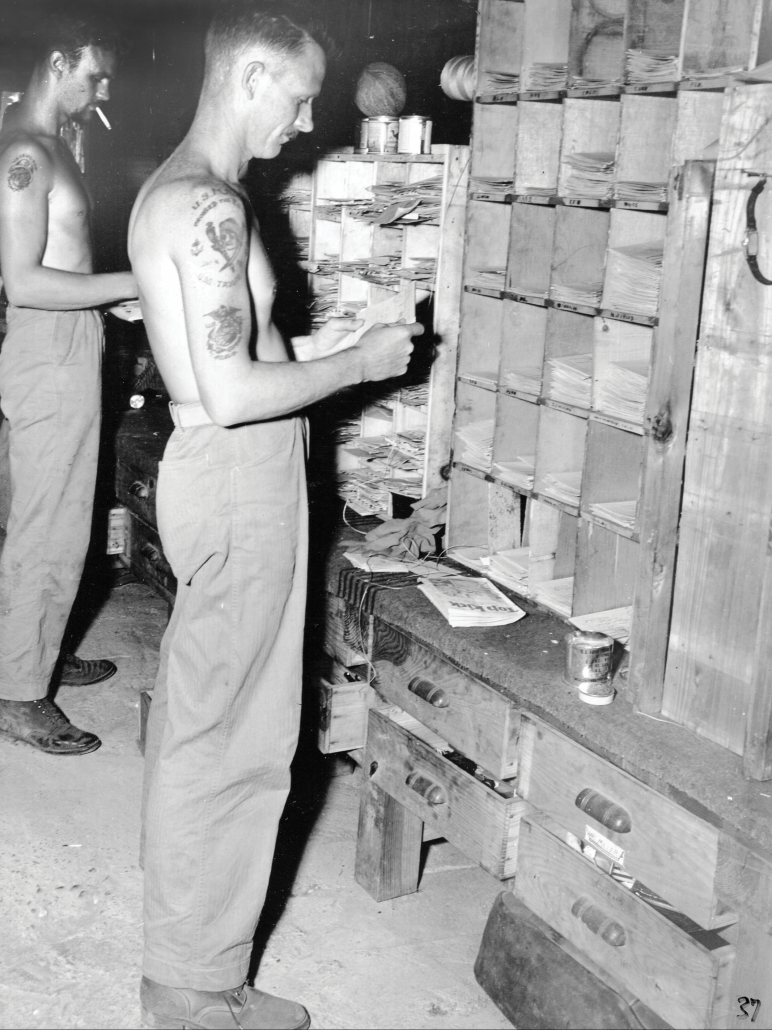

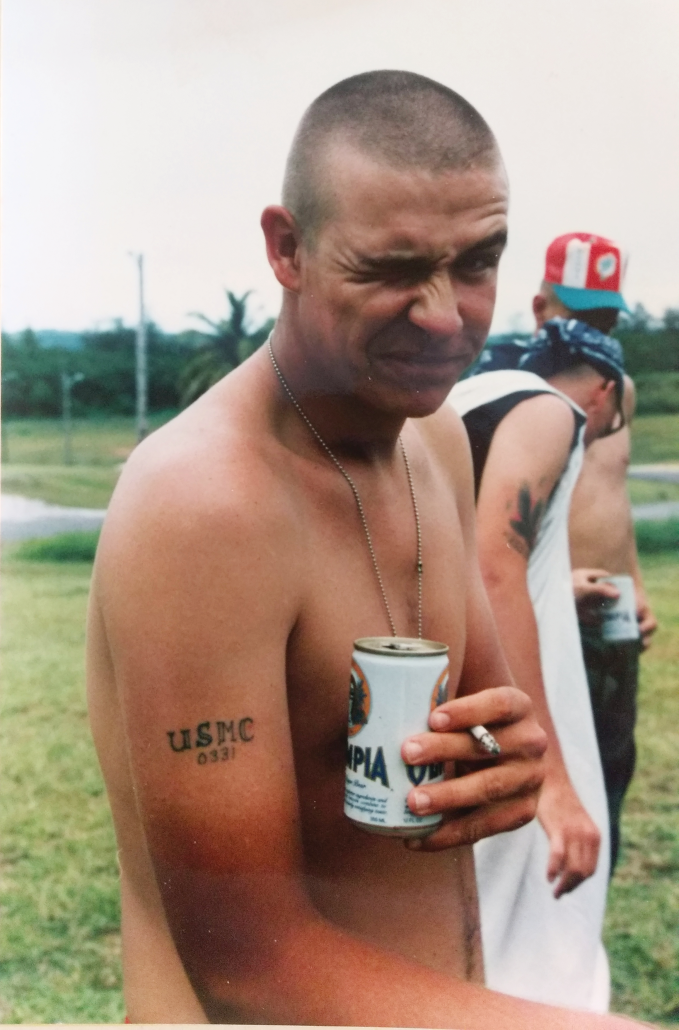

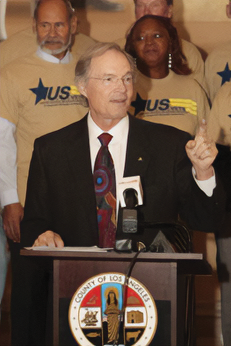

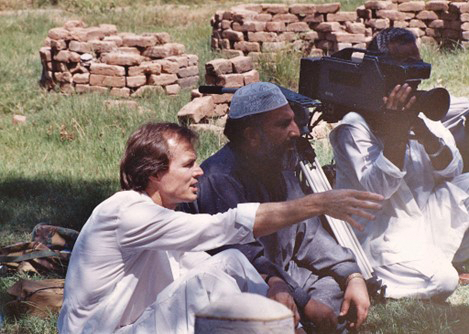

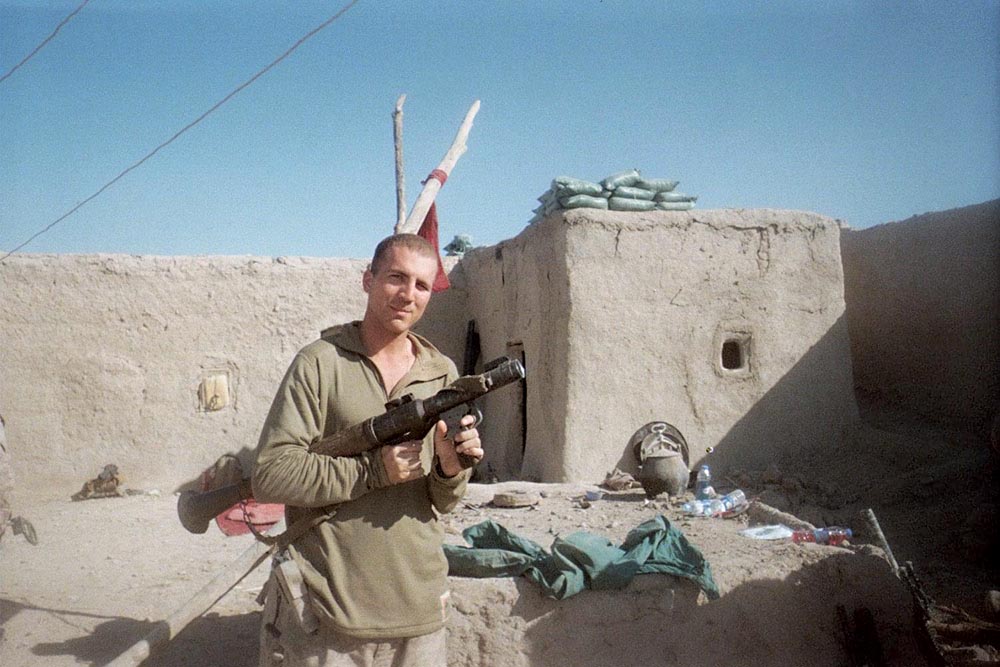

True disciples, spreading the belt-fed gospel with the enemy. (USMC photos)

In September of 2017, Adam Krick opened Instagram on his phone and created a new account. An idea had brewed inside his head for months. Too many accounts on Facebook or Instagram swooned over Special Forces, Special Operations, or any other “special” unit ad nauseam. Krick hoped to create a forum where he could recognize a tight-knit and motivated community that held a special place in his heart, the brotherhood of Marine machine-gunners.

From its humble origins, “Goons Up” rapidly evolved. Krick started by finding and following machine gunners with private accounts. Whenever they posted an inspiring photo or video, Krick asked if he could share it on Goons Up. The strategy worked brilliantly, and machine gunners across Instagram adopted “Goons Up” into the common language of the community. The account quickly became the online space where 0331s connected and celebrated their Military Occupational Specialty (MOS).

Krick tapped into a heritage and religion born long ago. His creation of Goons Up did not initiate this high level of enthusiasm for his beloved belt-feds. He simply gave it a modern place to focus its energy. Something has always been different about machine-gunners. All Marines take pride over other branches of the armed services because of, well, everything. The infantry pushes this further, understanding they represent the backbone of the Corps. Machine-gunners, though, adhere to a cult within a cult that takes it to the extreme. For many, this “loud and proud” sense of belonging is not just obnoxious words or behavior. It represents a way of life. It reflects a calling, where tactical and technical proficiency trump all the “oorah” chest beating and “Animal Mother” tattoos.

“When I came up through Infantry Training Battalion (ITB), I had no idea I’d become a machine gunner,” remembered Sergeant Race Kilburn, an 0331 currently serving as a Combat Instructor at School of Infantry-West. “I thought I would become a rifleman and be part of that main effort.”

When he came to the split in training where each student received their MOS, the ITB staff gathered the student body together. A Marine from each 03 MOS went on stage before them and gave a two-minute presentation covering their job and why all the students should want to be part of it.

Kilburn remembers the scene vividly.

“They had the rifleman come up and he says, ‘We’re the boots on the ground. We’re ready to put shit down. We are the main effort. Everyone else standing beside me right now is a support element.’ He went on and got the students all riled up. We all thought, ‘Oh man, here we go.’ Next, the mortarman comes up and he’s like, ‘We drop bombs from far away. Nobody can move without us.’ We were all like, ‘pffft, whatever.’ Then the assaultman comes up and says his piece and we all thought it sounded pretty cool. All these guys spent their whole two minutes talking about how cool their MOS was and building it up.”

“Then the machine-gunner came up to say his part. I still remember this guy. He came up to the stage and says, ‘Machine-gunners blow shit away, then the riflemen walk in to see everything dead. If you want to be a f—king machine gunner, you better be strong, you better be tall, and you better be tough.’ That’s all he said, then walked away. From that day on, I wanted to shoot belt-fed.”

These disciples of the belt-fed gospel extend through history, reaching back to the machine gun’s inception and implementation. Major Edward B. Cole served as the original prophet, authoring the Corps’ first “Field Book for Machine Gunners” in 1917. Cole became a martyr for the religion, dying a hero’s death in battle at Belleau Wood. Marines like John Basilone and Mitchell Paige arose as demigods in the eyes of future generations. Their grit and super-human feats of endurance formed the genesis of a holy spirit that all 0331s prayed might dwell within them. The award citations of dead machine-gunners long since passed wrote the gospel pages, setting high the standards for what was expected of anyone who believed they could carry the gun.

The success of Goons Up stemmed not just from the avid engagement of its followers, but also from the passion of its creator. Krick learned to eat, breathe, live and die by the gun through multiple combat tours as an 0331. The forefathers of his MOS inspired him to uphold their legacy. He took the machine-gunner’s creed to heart:

“We will cut our enemies down in droves. Our fires will be the substance of their nightmares. We will protect our brothers. The fields of the dead shall serve as evidence of our passing.”

Krick enlisted out of high school in April 2003 after watching the initial invasion of Iraq on TV. He joined 1st Bn, 2nd Marines at Camp Lejeune and deployed to Iraq for the first time in summer 2004. He returned to Iraq a second time in 2006 and a third time in March 2007, where he reenlisted. He spent three years of his second enlistment on Inspector-Instructor duty before ending his last year on active duty once more at Lejeune with 1st Battalion, 6th Marines.

Krick entered the civilian world as a forklift mechanic in 2011. He waited six years to create Goons Up and work towards his goal of establishing an 0331 community. As a husband, father, and full-time employee, Krick sacrificed sleep and other personal ambitions to create a brand worthy of the heritage it represented. He entered the realm of an aspiring entrepreneur only after the community took off. The success of his e-commerce store mirrored the success of his Instagram account, becoming profitable enough to support Krick’s wife and six children. In December 2020, barely more than three years after making his first post, Krick quit his civilian job to run his business full-time.

Today, Krick operates Goons Up from his home in Pennsylvania. With nearly 10,000 posts, a thriving e-commerce store, and incredible numbers of likes, shares, and follows, “successful” fails to adequately describe the business’s meteoric rise. Krick posts every day, often multiple times a day. He mixes in history and humor, while focusing the account on his original founding purpose to highlight machine gunners and the weapons they love so much. Krick no longer needs to solicit individuals for content to share. Marines and soldiers around the world send him their photos and videos, often posing with one of the numerous flags sold on his store.

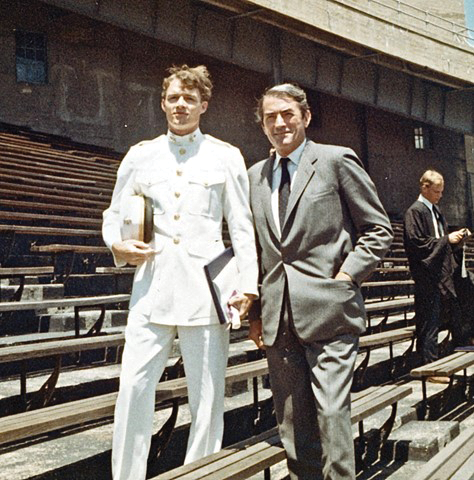

Maj Edward B. Cole, and GySgt John F. Basilone. USMC Photos.

Even as Goons Up fulfilled its mission to connect and recognize the infantry, Krick desired to do more. He wanted a way to formally recognize machine-gunners, beyond an “attaboy” post or a pat on the back. What if he could give them an award? Without something to physically hand out, the award would be nothing more than another post on Instagram. He considered small trophies and statues. Finally, Krick stumbled across another Marine veteran-owned business called Blue Falcon Awards.

Blue Falcon perfected the art of satire and mock representations of true military items. The business churns out rank insignia, badges, and challenge coins, all intended to look real until closer inspection reveals a gag alteration. Krick ended his search for the right type of award when he discovered Blue Falcon produced uniform medals, complete with custom ribbon colors and engraved images. With Blue Falcon providing his blank slate, Krick needed only to design and name the medal.

Naming his medal proved easy. For a United States Marine Corps machine- gunner, for anyone who knew anything about our Corps’ beloved history and the heroes associated with it, there could be only one namesake: Basilone.

Every Marine of every MOS learned the name in boot camp. Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone inspired generations of warriors through his heroics in combat. He was the quintessential Marine Corps machine gunner and remains the Great Section Leader in the sky.

On Guadalcanal, Basilone and his few remaining Marines fought tenaciously to hold off wave after wave of Japanese attackers. Basilone moved from position to position with desperately needed ammo, repairing machine guns in the dark, and firing a heavy machine gun from the hip with his bare hands. At least 38 enemy dead were credited to him before the night was out, and hundreds more to his Marines.

For his actions, Basilone received the Medal of Honor. His heroism, of course, proved only the beginning. His attitude was equally endearing. Basilone turned down a Presidential award ceremony, opting instead to receive the medal in the field, closer to his Marines. Next, he refused an officer’s commission and desk job in Washington, insisting he return to combat in the Pacific. (Editor’s note: See “I’m Glad to Get Overseas Duty” in the February 2022 issue of Leatherneck to read an essay written by Basilone about how he was eager to get back to the fight.) His further heroism and death in battle on Iwo Jima made him the only Marine of WW II to receive the Medal of Honor and Navy Cross and become one of the most iconic personalities in the history of the Corps. Other Marines before or since may have earned more medals, seen more combat, or done more for the image of our Corps. Even so, the legend of Basilone endures like Babe Ruth or Elvis. There simply can never be another Basilone.

Unlike other medals or trophies, the Goons Up medal was not merely named the “Basilone award,” in honor or remembrance of its namesake. Krick added an additional descriptor that would drive home his intent; the “Spirit of Basilone” award. Though the man is gone and confined to photographs or stories told countless times, his spirit lives on today, thriving within the 0331 community.

Several years after hearing the competing MOS pitches at ITB, Race Kilburn served as a machine gun section leader with “Kilo” Company, 3rd Bn, 5th Marines. In March 2020, he became the first recipient of the Spirit of Basilone award. Krick worked behind the scenes to confirm Kilburn truly embodied the life as a disciple of the belt-fed gospel. As a six-time recipient of the “Gung Ho” award from each of the formal schools he’d attended, and after being meritoriously promoted to Sergeant, Kilburn certainly fit the bill. Once confirmed, Krick drafted an award citation and mailed his newly designed medal to a common friend he shared with Kilburn. The friend invited Kilburn to a bar after work one Friday night where a small, informal gathering of machine-gunners surprised him and presented him with the medal.

Kilburn had followed Goons Up since its inception but had never heard of the Spirit of Basilone award. He studied the medal, seeming just as real as any other he might wear on his Blues. The words “Spirit of Basilone” arched in a semi-circle above a silhouette of the legend himself, engraved on a gold medallion. A golden M1917 heavy machine gun, like what Basilone used in combat, hung beneath a brown and green ribbon, connecting the pieces together.

“What the heck is this?” Kilburn asked.

The gathered Marines explained it was a new award created by Goons Up, presented to him, complete with individual citation.

“When I became the first recipient, I thought it was cool, but I didn’t know if people would take it seriously, or if it would just put a target on my back as the guy who was receiving recognition for something not valuable,” Kilburn recalled. “I didn’t realize how much it would blow up.”

Krick posted photos and information about his first recipient and how the medal would be given out moving forward. He began receiving nominations from different units around the Corps. Even Army units nominated soldiers for the award.

“I wanted to make something that went a little further in helping to instill that machine gun pride that we’re so known for,” Krick stated in each post covering a recipient of the award. “It’s nothing official, but that doesn’t make it any less meaningful, at least not to me. The Spirit of Basilone medal is not for sale. If you want it, earn it. If you think you know someone who rates it, let me know!”

Krick started presenting the award once a quarter. Since its creation, the medal has been presented 10 times. One of these awards went to a soldier, Staff Sergeant William Hendry, a weapons squad leader in Red Platoon, Fox Troop, 2d Squadron, 3d Cavalry. The method of delivery evolved as well, growing in formality and scale since Sgt Kilburn received his medal in a bar. Many recipients received the medal in a formal ceremony conducted by their platoon, with their platoon commander and platoon sergeant pinning the medal on their blouses. On at least one occasion, the recipient’s battalion commander got involved and presented the medal in a formal ceremony just like any other “real” award would be given out.

As of this writing, Sgt Taylor Mathis is the most recent recipient of the award. Mathis is an 11-year veteran of the Corps, currently serving as a machine-gun section leader with “Graybeard” Guns, Lima Company, 3rd Bn, 7th Marines. The Marines surprised Mathis with the award shortly after the unit returned home from their most recent deployment. With over a decade’s worth of ribbons and medals on his dress blues, Mathis still values the Spirit of Basilone award over anything else.

“Personally, I think this is the greatest award I’ve received,” said Mathis. “One, because my guys thought I was worthy of it, and two, having something named after Basilone, he is our legacy as machine gunners. I can’t really wear it on my uniform, but it’s something I can carry on forever. It’s probably the most humbling thing I’ve gotten so far.”

This sentiment proves true for many Spirit of Basilone recipients. Sgt Anthony Wendlandt received his medal in a surprise ceremony on a Friday morning in June 2022. It was already going to be a big day for Wendlandt. That same afternoon, after five years as a machine gunner with 1st Bn, 4th Marines, he picked up his DD-214 and left active duty. Receiving the medal on his last day in uniform held special meaning.

“I had gotten a Navy Achievement Medal earlier that year after our second deployment, which I’m proud of because it is a recognition that I actually did my job well. But the Spirit of Basilone award, to me, meant more that I had left an impression on the guys that came after me. It isn’t like you just met some certain criteria and get a medal for it. You don’t get it just because you did something and looked good in front of higher. You earn it by being a good Marine, a good machine gunner, and a leader.”

Wendlandt embarked from Camp Pendleton on a cross-country road trip. He stopped by Goons Up headquarters in Pennsylvania to meet Krick in person before continuing east. The journey became a pilgrimage of sorts, paying homage to the 0331 community, the legacy of John Basilone, and Wendlandt’s own good fortune, having had the privilege to be part of it all. He traveled to Basilone’s hometown of Raritan, N.J., where he visited the Basilone Statue and Veterans Park. The final leg of his journey brought him to Arlington National Cemetery. Wendlandt walked a quarter mile off the typically trodden pathways to section 12. There, below the Memorial Amphitheater and Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Wendlandt kept vigil over the grave of his medal’s namesake.

“To me it was very symbolic, bringing the award from California back to Basilone’s grave in Arlington. I didn’t even know he existed before I joined, other than watching “The Pacific” in high school. I thought the least I could do was to bring the award there and kind of have it come full circle. I still want to be what this award means; someone who gives a shit about being a machine gunner, is proud of being a machine-gunner, and did their job to the best of their ability every single day. I still have that spirit. I still have that pride, even post-military.”

Since the creation of the Spirit of Basilone award, other social media accounts affiliated with Goons Up have followed suit. “Tubes Up,” an account dedicated to mortarmen, drew inspiration from famed Marine and author Eugene B. Sledge, best known for his epic memoir, “With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa.” The “Spirit of Sledge” award recognizes mortarmen today who embody his spirit. Another account, “Corpsman Up,” quarterly presents the “Spirit of Ingram” award to U.S. Navy docs serving with Marines. Their medal is named in honor of Hospital Corpsman 3rd Class Robert Ingram, a Vietnam War veteran and recipient of the Medal of Honor and the Silver Star. As “unofficial” awards such as these continue gaining recognition, only time will tell how they will evolve and the impact they will make.

In an online world of slander, negativity and pointless memes, Goons Up serves as a beacon of hope for what social media can and should be. The community recognizes people who care about their job. It encourages Marines to consider why they joined in the first place, and what they can do to make their MOS better.

“I give all the credit to Adam for starting the ripple, that turned into a wave, and into a tsunami of a community through social media that is 100 percent backing the Marines who want to do good in the Marine Corps,” said Sgt Kilburn. “How many meme pages are out there, or how many pages complaining about how dumb things are, or how our commanders are not smart and don’t know what we should know? With all of that going around, I think it’s good to see we are winning the fight on social media of give a shit about your job and it will give back.”