Night Battle on Tinian: Marines Engage With Enemy Tanks

By: Steven D. McCloudPosted on June 15, 2024

Executive Editor’s note: This article is based on interviews and research done for the author’s book “Black Dragon: The Experience of a Marine Rifle Company in the Central Pacific.

Private First Class Bob Funk struggled to clear his head as he lay in the roadside ditch, peering into the blackness of the night. His buddy, PFC George Michalet, was next in line behind him. They and four other Marines had already lain there for hours, soaked with rain and sweat, taking turns trying to stay awake.

They had only finished mopping up Saipan a week before. Only half of “Fox” Company, 2nd Battalion, 23rd Marines remained. The rest of those who had survived Saipan were in hospitals around the Pacific, 59 of them in Naval Hospital No. 10 at Aiea Heights on Oahu. The 129 who remained were in poor shape. Even Easy Company’s commander, Major Lester Fought, was out of action with dengue, and it seemed that most had at least a touch of it. But for Funk and Michalet, this outpost job had sounded easy enough, even if they had been in the Marine Corps long enough to know better than to volunteer.

They had been sure that, after a month on Saipan and being saddled with the unsavory week-long job of mopping up and clearing caves on the northern part of the island, they would be allowed to sit out the Tinian operation. They had taken some solace in being made the reserve. But there they lay on outpost the first night, waiting for the enemy response to the landing and awaiting the arrival of some 37mm guns to join them. So much for being in reserve.

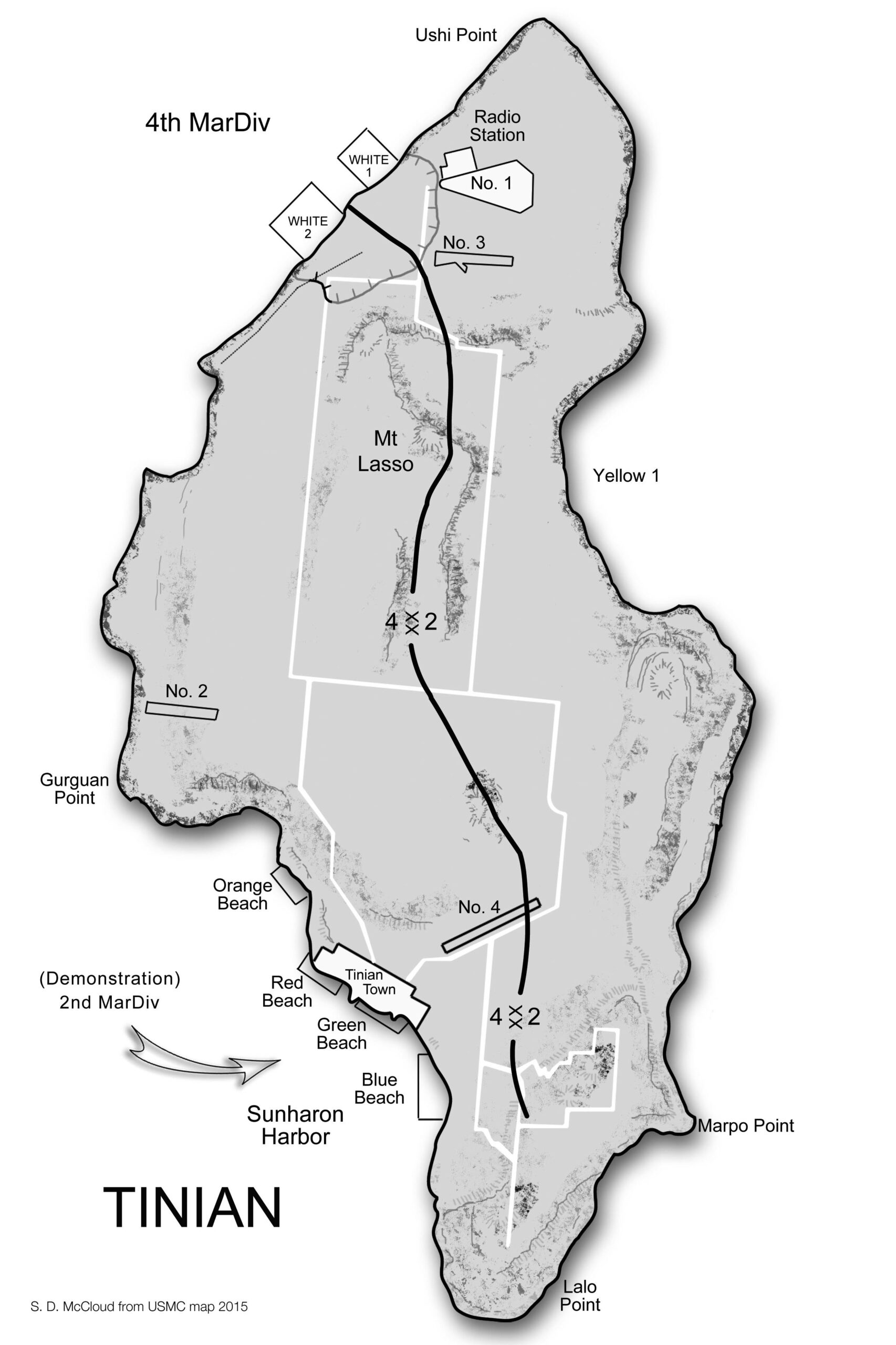

The 4th Marine Division had made the unlikely landing that morning across two tiny beaches near the northern tip of Tinian while 2ndMarDiv held the main Japanese force in place with a feint landing 5 miles south at Tinian Town. As July 24 turned into July 25, 2nd Bn, 23rd Marines formed the far right section of the division beachhead.

Funk and Michalet lay astride a narrow coral road that ran back to the company line, some 200 yards behind them. It also led straight ahead, all the way south to Tinian Town, where the bulk of the 9,000 Japanese defenders were believed to be. They peered out into the darkness, knowing the enemy was out there. And still they waited for the 37s to arrive.

Three hundred yards back toward the beach, Eddie Davis settled into his hole near Fox Co’s command post. A 20-year-old field music, Davis had covered a lot of ground on Saipan as one of the company’s runners. It was after midnight when he got the call from company commander Captain Jack Padley.

“I’m in a nice comfy foxhole,” Davis recalled. “Padley said, ‘Davis come over here.’ And I knew exactly what he was asking me to do. He said, ‘Do you know where the regimental CP is? Well you go get the 37s and put them there up on the line.’ ”

The 2nd Bn, 23rd Marines had already placed its attached platoon of 37mm guns on the line, facing an open cane field to the southwest, the battalion’s front and the division’s far right flank. Ready with canister rounds, those four weapons stood ready to repulse the expected infantry attack. But the little coral road from Tinian Town pierced Fox Co’s position from the left. That was the likely approach for enemy tanks, and Colonel Ogata had a company of them. To cover the road, Padley borrowed the four guns normally attached to 3rd Bn, which was the division reserve.

Davis set off into the darkness and was challenged for the password three times along the way by his fellow Marines. Some 500 yards later, he was directed to 3rd Bn’s reserve area and eventually led to platoon Sergeant James Tillis, commanding the 3rd antitank platoon in the absence of First Lieutenant Charles H. Taylor, who had been evacuated from Saipan. Davis led Tillis back to Capt Padley, who sent them forward to 1stLt Charlie Ahern, who was on the line with 1st Plt, under Japanese infantry attack. Joined by corpsman Owen H. Bahnken, the trio set out across a field now illuminated by flares.

“I was informed by Lt C.J. Ahern,” Tillis wrote later, “that I was to take up a position astride the main road running north and south almost the entire length of the island.”

By the time Davis and Tillis reached the designated area, the enemy attack hundreds of yards behind them had apparently dwindled and, with it, the light of flares. “The night was pitch black,” Tillis explained, “making reconnaissance very difficult. Although after a time I was able to pick out positions for the four 37mms of my platoon.”

Davis and Tillis returned to 3rd Bn for the order to move up the gun sections. Then, using two jeeps, the Marines pulled the four guns to the line, two at a time. “The platoon was in position and dug in at about 0220,” Tillis reported.

Davis’ mission accomplished, he left the guns to set up and headed back to his hole.

Tillis placed one gun to the left of the road and three to the right, one of them commanded by Gunnery Sergeant Charlie Kohler. “I was just right next to the road, barely off to the right,” Kohler explained later. “And from my position, I could fire almost straight down that road. We were all about 25 or 30 yards apart.”

Kohler had no idea that, ahead of him, at the crest of the gradual slope, six Marines lay beside the coral-topped road. And 100 yards ahead, Funk, Michalet and the others lay in the ditches, trying to stay awake and still awaiting the arrival of a single 37mm. They had no idea Kohler was behind them.

Funk peered into the darkness ahead, listening to a bizarre mix of sounds. He kicked Michalet’s helmet to wake him.

“Mitch, I hear enemy tanks,” whispered Funk.

“Aw, you’re nuts,” Michalet replied. “Those are just some Marine trucks or something.”

“Bullshit, those are Japanese tanks,” Funk said.

A hundred yards back, Kohler heard them too. “We heard ’em coming,” he recalled. “My god, you could hear ’em coming, 9 miles away.”

Funk and Michalet were stunned as a tank suddenly whizzed past them on the road, 3 feet from their heads. Worse yet, Michalet looked around and found that the other Marines had pulled back without them. The two of them were alone.

Back near the company CP, Eddie Davis was just settling into his hole when he heard the squeaking sounds of tanks. “Oh boy, we got ’em,” he said. “Those 37s are up there and they’ll knock ’em out.”

But evidence indicates that, in the darkness, the lead tank crested the hill and was past the gunners before they could react. It came to a halt just before reaching Fox Co’s line and sat idling in the quiet. Indications are that the infantry attack on the right had hit a lull at this time. Sergeant Bill Wyckoff was one of the Marines who had pulled back. “We were in a drainage ditch, right next to the road,” he recalled. “And they stopped right by us. And I think, ‘Oh God, don’t let a flare go up.’”

Fox Co Marines Leonard Ash and Don Milleson were horrified to see the tank in their midst. They huddled in their hole, wondering why the 37s had not fired. By all accounts, no flares were up and not a shot had yet been fired. Everyone was caught in a state of disbelief. Third Plt’s bazooka team, Walter Fritz and Bill Myers, was with Ash and Milleson. “Fritz was so close to the road,” recalled Ash, “that when the Japanese tank stopped by him, he couldn’t swing the bazooka around because it would hit the side of the tank.”

The Marines held silent. Finally, the little tank began to roll again, down into 3rd Plt, where it stopped once more. Sergeant Sam Haddad was nearby. “The tank was so close that we couldn’t depress the guns we had. The treads were right here.”

Just as a flare went up, the tank commander opened the hatch for a look. Immediately the silence was broken by the thunder of a Browning Automatic Rifle, killing the commander. The tank’s driver gunned the engine, racing farther into Fox Company’s position. “When the tank got past the end of the cane field and the railroad tracks,” recalled 3rd platoon’s Private First Class Don Swindle, “it ran through the Company F foxholes, but the guys were able to roll out and I don’t think anyone was hurt.” First platoon’s bazooka man, Corporal Leroy Surface, chased it down and destroyed it with two shots.

Fire erupted all along the line as flares now illuminated the battlefield. Back up front, Funk and Michalet lay in the ditch ahead of Fox Company’s line. “We did not dare breathe or move,” recalled Funk. “We stayed put because we were in their line of fire.”

The two Marines had no idea what was coming at them. Some 300 yards across the cane field to their left front was an old friend from the company’s early days in North Carolina, Captain Henry Van Joslin, now commanding Fox Company of the 25th Marines. Joslin later recalled, “As the flares from the ships dropped over our position, we could see five tanks coming down the road unbuttoned and a group of foot soldiers following close behind all in a bunch.”

“Just then,” recalled Funk, “here comes tank number two and, of all the dumb things to do, he stops right next to us, inches away.”

The tank was swarming with enemy troops holding tree branches for camouflage in the middle of a dark night. “That’s just stupid,” thought Funk.

The two Marines kept their heads down. “The whole Marine Corps must have opened up on this tank,” Funk recalled, “and the Japanese were jumping off over us and running for their lives. Something hit the tank and it started to burn.”

The hit came from Charlie Kohler’s 37mm, 100 yards back, now firing antitank and canister rounds, scattering the Japanese infantry. “I was able to shoot the first tank,” he explained. “And he spun around, and we started knocking the hell out of them. They jumped off the tank, you know. We stopped it right there and blocked the road.”

“It was stopped in the middle of my position,” wrote Tillis, “where it exploded and began burning. This gave us sufficient illumination to sight in on the rest of the column.”

“The first burning tank was right next to us,” explained Funk, “the machine-gun and rifle fire had us pinned down in the ditch that wasn’t deep enough to carry water, and about that time here comes number three, full speed down the road toward us. As I looked up, this driver was coming right at us with one track in the ditch. If we move, we’re shot. If we roll out, a [Japanese soldier] might get us. Just at the last he pulled back up onto the road and pulled up right behind the burning tank, and they began yelling at each other. They decided to back up, only to be hit and start burning.”

Kohler was certain that his gun also scored this hit. “We could see pretty damn good with those big flares that the Navy was able to shoot up there in the sky. We could see all the [enemy troops] moving around—just black shadows, but we could see them. They made a real easy target. We blocked the road. So they had to spread out. And when they spread out, they were getting into the other Marines who were on the line.”

Behind them, Fox Company’s line had unleashed its firepower in the light of the burning tanks. “They burned brightly enough to illuminate the open field,” recalled machine-gunner PFC Jules Hallum. “At least they gave silhouettes to the attackers. We opened up with everything we had.”

“We had to lay there in the ditch next to those burning tanks while the line was trying to shoot everyone who was in front of them, including the two of us,” recalled Funk.

Japanese troops leapt onto them from the tanks, some wounded, some ablaze, others decimated by canister and machine-gun fire. Funk and Michalet began to push forward over the crest of the hill to get out of the line of fire. “We crawled over bodies, gear, and anything that was in our way. Rifle and machine-gun fire continued over us like were on a training course. Another tank sped by without stopping, so not to worry about him.”

The fifth and sixth tanks broke off the attack momentarily, until the fifth returned and raced through at high speed. A 37mm gun crew managed to get off a single armor-piercing round that went completely through the tank with no apparent effect. It broke into Fox Co’s lines, where Cpl Surface and Sergeant Arthur Metras again chased it down and destroyed it. Both men were recipients of the Silver Star for their action.

The sixth tank apparently veered close enough to Fox 2/25, that PFC Bascom Jordan destroyed it with his bazooka. So dark was it that, according to their Gunny Sergeant Keith Renstrom, Jordan bumped into the tank with his bazooka before seeing it.

“And it stopped,” explained Renstrom. “Then he backed off and shot his bazooka into it and got wounded by his own shell. And then the Japanese officer came out of it, and I shot him. After I shot him, he stumbled and fell, then we rolled his body back up against the tank.”

Jordan and Renstrom were also original Fox 2/23 men back in North Carolina until the regiment split to form the 25th Marines.

For the next couple of hours, 2nd Bn’s position was attacked from front and left by infantry from the Japanese 50th Infantry Regiment and the attached 1st Battalion, 135th Regiment. Fox and Easy Company’s line fired as they never had before during the war, all under light of flares. “The sky was full of them,” recalled Swindle. “You could look right out there just like broad daylight, and you could see [the Japanese] all over. And all down the line there, machine guns were hammering the hell out of them.”

“The fight was over before dawn,” recalled Hallum. “I went to sleep to a background chorus of groans of dying [enemies]. Maybe some of our guys too.”

Funk and Michalet managed to survive by crawling forward, out of the line of fire. And there they remained until light, when they were confronted with the dilemma of how to return safely to the line.

Hallum was perplexed to see his old schoolmates marching down the hill from enemy territory, and he could see from the look on their faces that they were not pleased.

“Bob came back to our area cursing at us for leaving him up there. He came over the next morning and just chewed the shit out of us. Our gun was firing right across, and he was in that ditch. He says, ‘you were hitting 4 inches over us.’ ”

Post-action attempts to make sense of the action in the 2nd Bn zone that night concluded that the tanks had fought through an artillery barrage to break through the lines. But the Marines on the ground were very clear. Not a shot had been fired, nor a flare sent into the air when the barely discernible shape of the first tank appeared in their midst.

Fox Co men heard that the gunners initially had canister rounds loaded and could not fire. The gunners say that is not the case. But consideration of the conditions and an understanding of the ground on which the action occurred can offer clues.

Funk and Michalet had been positioned at the crest of the gradually sloping hill. The tank had overtaken them suddenly. With any light, it would have appeared suddenly over the crest to Kohler’s gun crew, just a short distance back, set up on the reverse slope looking uphill. But the “pitch black” darkness noted by Tillis prevailed at that time. “Not having any night firing attachments for the anti-tank weapons,” he wrote, “the crews held their fire until the tanks were at point blank range.”

In that darkness, the gunners never saw the tank until it was upon them as suddenly as it had been with Funk and Michalet just moments before. As soon as the flares went up, they were in business, and it seems clear that Kohler’s gun crew knocked out the next two tanks by Funk and Michalet. After that, hits came from all directions.

The 23rd Marines incurred 241 casualties on Tinian, wounded and evacuated, killed, or missing. Another 256 Marines were evacuated due to sickness. One of them was Funk, who was flown to Saipan for six days in the Army field hospital with dengue.

Author’s bio: Steven D. McCloud, is a leadership consultant, coach and speaker, founder of TridentLeadership.com, and author of “Black Dragon: The Experience of a Marine Rifle Company in the Central Pacific.” He conducts PMEs and battlefield staff rides for corporate and government agencies. He also leads small-group expeditions to battlefields in the Pacific and Normandy.