Montford Point to Iwo Jima: Combat Bridged the Racial Divide

By: Cyril J. O'BrienPosted on February 7, 2025

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the April 2005 issue of Leatherneck Magazine. In recognition of Black History Month, Leatherneck is re-publishing the story.

The splashes of bullets in the water and the cresting of puffed bodies in the surf revealed a world turned upside down for the noncombat-designated service and support black Marines thrust precipitously into the first hours of the first day on the cutting edge of the battle which would emblazon itself in military history for its ferocity, heroism and sacrifice.

On that D-day morning of 19 Feb. 1945 on Iwo Jima, Corporal Gene Doughty, a Marine squad leader, pressing his belly into the coarse black sand, swiveled his head to count noses of his 1 st Squad, 1st Platoon, 36th Marine Depot Company.

“They were all flat as rugs with the salt air above them singing with shell splinters,” recalled Doughty. A fellow Marine, Private Wardell Donaldson, his head embedded in the sand, had a bullet hole in his helmet. Surf washed the prone boondockers of many who were hardly ashore.

Into that same fury that morning came additional brother black Marines, members of the 8th Marine Ammunition Co. Both the 36th Marine Depot Co and the 8th Marine Ammo Co were part of the 8th Field Depot, which provided service support for the Third, Fourth and Fifth Marine divisions of V Amphibious Corps (VAC).

These young men were part of a distinctly select group-20,000 vigorous, patriotic Americans known today as Montford Point Marines. During World War II, black Marines were recruited and then trained at a segregated camp, Montford Point Camp, near Jacksonville, N.C. They served in two defense battalions and as combat service support Marines, such as truck drivers, security details, cargo suppliers and ammunition handlers. They were not slated for direct confrontation with the enemy. All officers in the active units were white, as were most of the noncommissioned officers in the beginning.

Doughty, celebrating his 21 st birthday on Iwo Jima with the 36th Marine Depot Co, came to the beach beside the 8th Marine Ammo Co at virtually the same time as assault troops. However, the depot and ammunition forces had to wait for space on the 3,000-yard beachhead. In a few days, the 33d and 34th Marine Depot companies and succeeding elements of 8th Marine Ammo Co entered into no less a conflagration. They’d be protecting, sorting or delivering essentials to troops within earshot.

“But on this spit of a beach, on a lone rock in the open sea,” recalled Doughty, “the enormous swells often picked up landing craft and crashed them bodily ashore.” Ammunition, water tanks, assorted military equipment, rations-all were dumped unceremoniously on the strand. With the crunch of mortars, artillery water spouts and whining shell fragments close enough to startle your ears, black troops, often standing upright, were provisioning the battle.

“They were so young-many 18 to 19 [years old], really. It took great care, and slowly, to ready it all,” added Doughty, “with thanks to those brave Army brothers with the DUKWs [‘ducks’-wheeled amphibious landing craft, all-purpose carriers], and the Pioneers and naval construction battalions [Seabees] with their armored ‘dozers’ and Weasels [small, tracked carriers]. In those first hours, supply was hand to mouth.”

An Army officer, second lieutenant Bruce Jacobs, who was attached to the Army DUKW units, expressed the wonder of how they survived it all. The Army lieutenant celebrated his 20th birthday on the island. A retired major general, he lives in Alexandria, Va.

Sergeant Thomas Hay wood McPhatter of Lumberton, N.C., who also celebrated a birthday on Iwo, plunged headlong into the pandemonium as a section chief in 1st Pit, 8th Marine Ammo Co. “Our unwieldy LST [tank landing ship] forced a keel-grip on the sand,” recalled McPhatter. “But [she] swung to the drumming of the heavy surf. Ammo Marines were soon into her gaping bow to wrestle out the munitions. Japanese big-gun rounds and machine-gun splatters took umbrage.”

Action was continuous. On the second day, 2dLt Francis J. Delapp and CpI oilman Brooks, both from 8th Marine Ammo Co, were wounded. On the third day, Private First Class Sylvester J. Cobb of the company was wounded.

The 34th Depot Co, which landed with the 33d Depot Co on Feb. 24, lost CpI Hubert E. Daverney and Pvt James M. Wilkins, killed on the fire-swept beach. A few days later, Sgt William L. Bowman, PFC Raymond Glenn, Pvt James Hawthorne, PFC William T. Bowen and PFC Henry L. Terry were out of the battle with wounds. In early March. PFC Melvin L. Thomas gave his life and Pvts “J” “B” Saunders and William L. Jackson, all 8th Marine Ammo Co leathernecks, were wounded.

“Why?” asked McPhatter. The answer was simple. There was no shelter, no defilade and no concealment; all operations on Iwo Jima were front line. “Death came from anywhere, to anywhere. Pick any Marine,” said McPhatter, “and you’ll hear high words for our Seabees. They went out of their way to bring water up to us later.”

But the gods of war momentarily turned their backs and “like a lightning stroke, a mortar round or two dropped into the ammunition dump that 8th Ammo was burgeoning,” said McPhatter. “We were in foxholes right beside the dump.” The blowup seemed a fizzle at first, then a great thunder with shrapnel flying every which way.

“We raced away and down to the beach for safety and to assemble what we could,” he explained. “It was a disaster. So much ammo was destroyed. We needed instant supply from Guam and Saipan. The planes were soon [overhead] and [the] munitions [floated down] under brightly colored parachutes [that] the Japanese could see very well. The Japanese potshot at the Marines running helter-skelter anywhere the wind blew the chutes. Things got really intense, kicking up the sand.”

McPhatter ducked momentarily into a gutted bunker, stopped beside a dead Marine “who, no doubt, died only moments before as he held the photographs of his family to his blooded chest. With my helmet I scooped a shelter for my head and promised the Almighty that if he spared me at this moment, I’d dedicate the rest of my life to Him.”

The sergeant kept his word. He entered the ministry, graduating from Johnson C. Smith University, Charlotte, N.C. Then after being a pastor, he entered the U.S. Navy Chaplain Corps, went on to serve in Vietnam, retired as a Navy captain, and holds a doctor of divinity from the Interfaith Theological Center, Atlanta. He’s now a retired Presbyterian minister.

McPhatter’s platoon leader, 2dLt John D’Angelo, now a retired schoolteacher, had high words for the coolness, drive and skill of his men. D’Angelo retired as a Marine captain.

Pvt Roland B. Durden, born in Harlem, N.Y., remembered when the dump blew, but the lump still in his throat is for the cost of the operation after only a few hours ashore. His 34th Marine Depot Co was part of the Graves Registration unit.

“We were day on, day on, day on burying them in long, bulldozed trenches, first wrapped in ponchos, then sheets, and finally nothing at all,” Durden said, “and these were the casualties of only the first days.” Durden retired as assistant general manager of the New York City Transit Authority.

Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone, who was awarded the Medal of Honor for action on Guadalcanal in 1942 while he was a sergeant, was among the dead, recalled Platoon Sergeant Stephen Robinson, later a prominent Illinois attorney, whose detail buried Basilone.

Samuel Saxton, a U.S. Navy steward, was there too, with the goods of war on an LSM, a medium landing ship. “Shell spouts meant God was with us and they were bad shots. I learned of guns concealed behind great steel sliding doors on Suribachi. But-and luckily-the snarling little carrier hornets tempered the enemy gunners’ zeal.”

Saxton joined the Marines later, rose to captain, served in Vietnam, and became a prominent Marine corrections officer, a profession he carried into civilian life with national recognition.

Actually, in early Marine Corps planning, black Marines were not slated for “direct confrontation with the enemy,” save those assigned to the 51st and 52d Defense battalions. The defense battalion role was to protect, and the Marines were combat-trained to do that. But many defense battalions were assigned remote spits in the Pacific that the Japanese didn’t care about. So neither 51 st nor 52d fired a round in anger, although some rounds were fired in frustration. As a historical footnote, the leathernecks of 51st Defense Bn did fire eleven 155 mm rounds to ward off a rumored Japanese submarine near Nanomea Island in the Pacific. However, other black Marines in the notfor-combat service support troops were again and again on the front lines and on invasion beaches to assist the assault forces.

But the Marine Corps plan for black Marines didn’t work all the time-especially around 5:15 in the morning on Iwo Jima, 26 March 1945. “We were security forces for the sleeping airmen, and we were more relaxed now that the islands had been secured for [10] days, but our perimeters were as tight as ever,” explained Doughty. “About 300 enemy, in a last-ditch incursion, slipped down the west side of the island and stormed the bivouacs of Army, Navy, Marine and Air Corps airmen.”

The Japanese were to carry out the dictum of their honored commander, Lieutenant General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, who stated, “Take 10 Americans with you!” Silent at first, the Japanese slashed the guide ropes of the tents and then slashed the sleeping aviators, many helpless and immobile under the fallen canvas that blanketed them-all in the dark before the dawn.

Hit hard was the Army’s VII Fighter Command. Bivouacked alongside them were the 5th Pioneer Bn and 8th Field Depot, where seasoned veterans were encountered. They blunted the attack in their sector with casualties and high honors.

“Oh, it was well planned,” said Doughty. “[They] came at us from three directions. They wanted maximum confusion and destruction, but because we were in foxholes, combat situated and ready, we were fast to respond. I recall James Whitlock and James Davis [36th Marine Depot Company] rapidly cranking off rounds, flashes on flashes in the dark. They [the Japanese] were bloody with their bayonets and swords. With a little later backlighting, our people could see faint wispy sword-swinging, grenade-sowing figures as they charged us.”

According to the Marine Corps historical pamphlet, “Blacks in the Marine Corps,” written by Henry I. Shaw Jr. and Ralph W. Donnelly, and reprinted by the History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps in 1988, “The black Marines were in the thick of the fighting.”

Pvt James M. Whitlock and PFC James Davis of the 36th Marine Depot Co each were awarded the Bronze Star Medal. Pvt Miles Worth of the 36th Depot Co was wounded. PFC Harold Smith was killed and CpIs Richard M. Bowen and Warren J. McDaugherty of the 8th Marine Ammo Co were wounded. Sgt McPhatter recalled that one of his Marines, PFC Burnett, first became aware of the Japanese incursion and “began firing to alert everybody.”

The infiltrators attacked with their own as well as American weapons. Forty of the Japanese dead were armed with swords indicating a high percentage were officers or senior noncommissioned officers. LtGen Kuribayashi was not among them. He earlier had committed hara-kiri.

Later, Colonel Leland S. Swindler, who commanded 8th Field Depot during the Iwo Jima operation, lauded the performance of his men, who continued to function in labor parties while in direct contact with the enemy. Proper security prevented their being taken unaware, as they conducted themselves with marked coolness and courage.

Some of the Marine Corps’ early savants had questioned why any robust combat training for labor troops was needed. Such were not the thoughts of the crusty hard-nosed black drill instructors at Montford Point. Take the legendary Gilbert H. “Hashmark” Johnson, who said, “I’m an ogre but fair.” Johnson attained the rank of sergeant major.

Another black DI during the early days at Montford Point, Edgar R. Huff, who also retired as a sergeant major, once stated, “You’ve got to be better than any Marine in New River.”

The door was opened in June 1941 for blacks to serve in all the military forces on orders from President Franklin D. Roosevelt. A year later, the Marine Corps activated the Montford Point Camp, and the Marines were quick to put in charge some shake-hands-with-the-devil black drill instructors such as Johnson and Huff.

Doughty recalled Johnson bellowing at the Montford Point training center. (The camp was later renamed Camp Gilbert H. Johnson in honor of SgtMaj Hashmark Johnson.) “Looking back at my early recruit training, I am ever grateful to its instructors and training personnel,” said Doughty.

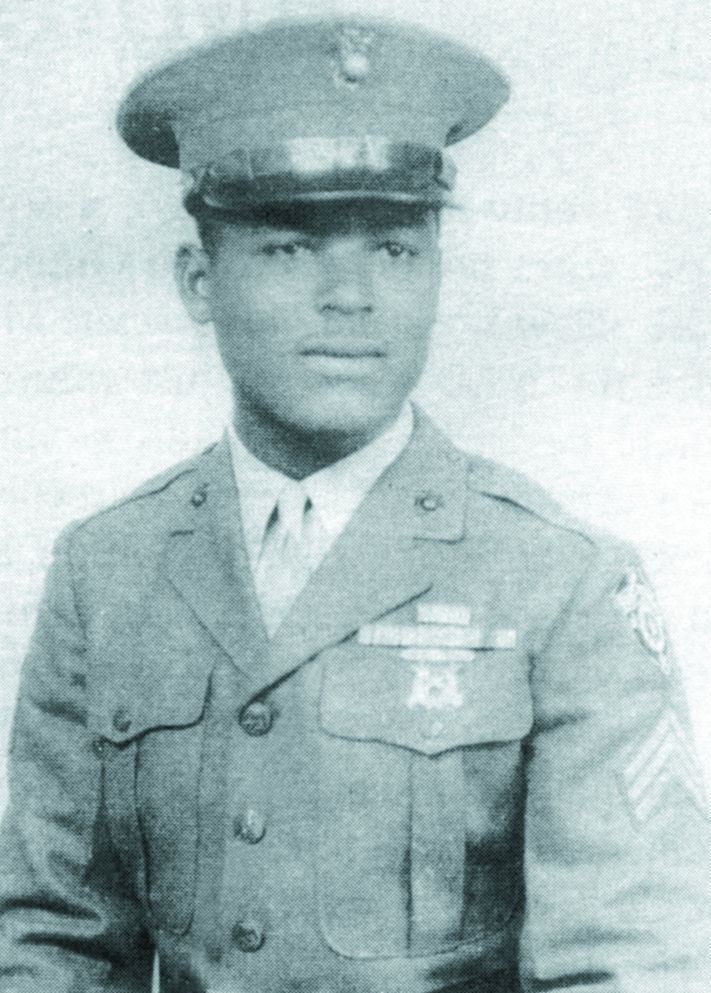

Doughty was promoted to sergeant for leadership shortly after the Iwo Jima campaign. He served with occupation forces at Sasebo Naval Base, Japan, was honorably discharged in May 1946 and returned to New York, where he resumed his college education at City College. His career included work as a physical education instructor for the New York City Police Athletic League and as a social investigator for the Department of Social Services. He retired from Sears, Roebuck and Co. as a communication division manager.

Doughty remains close to Marine Corps service organizations. He has been a member of the Marine Corps Scholarship Foundation for 25 years and served with its board for four years. He also is a life member of the Marine Corps League, 1 st District. He was national president of the Montford Point Marine Associationelected to two separate terms-and currently serves as its national scholarship program director.

General Carl E. Mundy Jr., 30th Commandant of the Marine Corps, addressing a reunion of Montford Point veterans, cited their “guts, determination and boundless drive to succeed and excel.”

Brigadier General Edwin H. Simmons, USMC (Ret), Director Emeritus, Marine Corps History and Museums, added, “Their role on Iwo Jima as well as Saipan, Okinawa and other battlefields made the simple statement: They were Marines and fought as Marines. Their spirit, combat skills, courage and devotion left no question of that.”

Authors note: For their actions as part of the supporting forces of VAC on Iwo Jima, the black Marines earned the Navy Unit Commendation ribbon. The “Navv and Marine Corps Awards Manual, secNAVINST 1650.1″ reads, “To justify this award, the unit must have performed service of a character comparable to that which would merit the award of a Silver Star Medal for heroism or a Legion of Merit for meritorious service to an individual.”

Editor s note: Cy O ‘Brien served as an infantryman in a rifle company in the Third Marine Regiment on Bougainville. He was later a combat correspondent on Guam and Iwo Jima. Following WW II he spent 12 years in the Marine Corps Reserve, retiring as a captain. Cy was first published in Leatherneck in August 1944 and remains a valued contributor.