Lejeune: A Leader Ahead of His Time

By: Maj Skip Crawley, USMCR (Ret)Posted on February 15, 2024

Ask any Marine who among the pantheon of notable and illustrious Marines between World War I and World War II were most responsible for the Corps becoming the premier amphibious assault force in the world during the Second World War and many names would be mentioned: The iconoclastic Major Earl “Pete” Ellis, whose ideas and assumptions, according to authors Jetek A. Isley and Philip Crowl, “became the keystone of Marine Corps strategic plans for a Pacific War;” Major General Commandant John H. Russell (1934-1936), who author Merrill Bartlett said “guided the development of amphibious doctrine, preparing the Marine Corps for its major contribution in World War II;” and Lieutenant General Victor H. Krulak, who played key roles in the development of the Landing Vehicle, Tracked (LVT) and the ubiquitous Higgins Boat as a young officer.

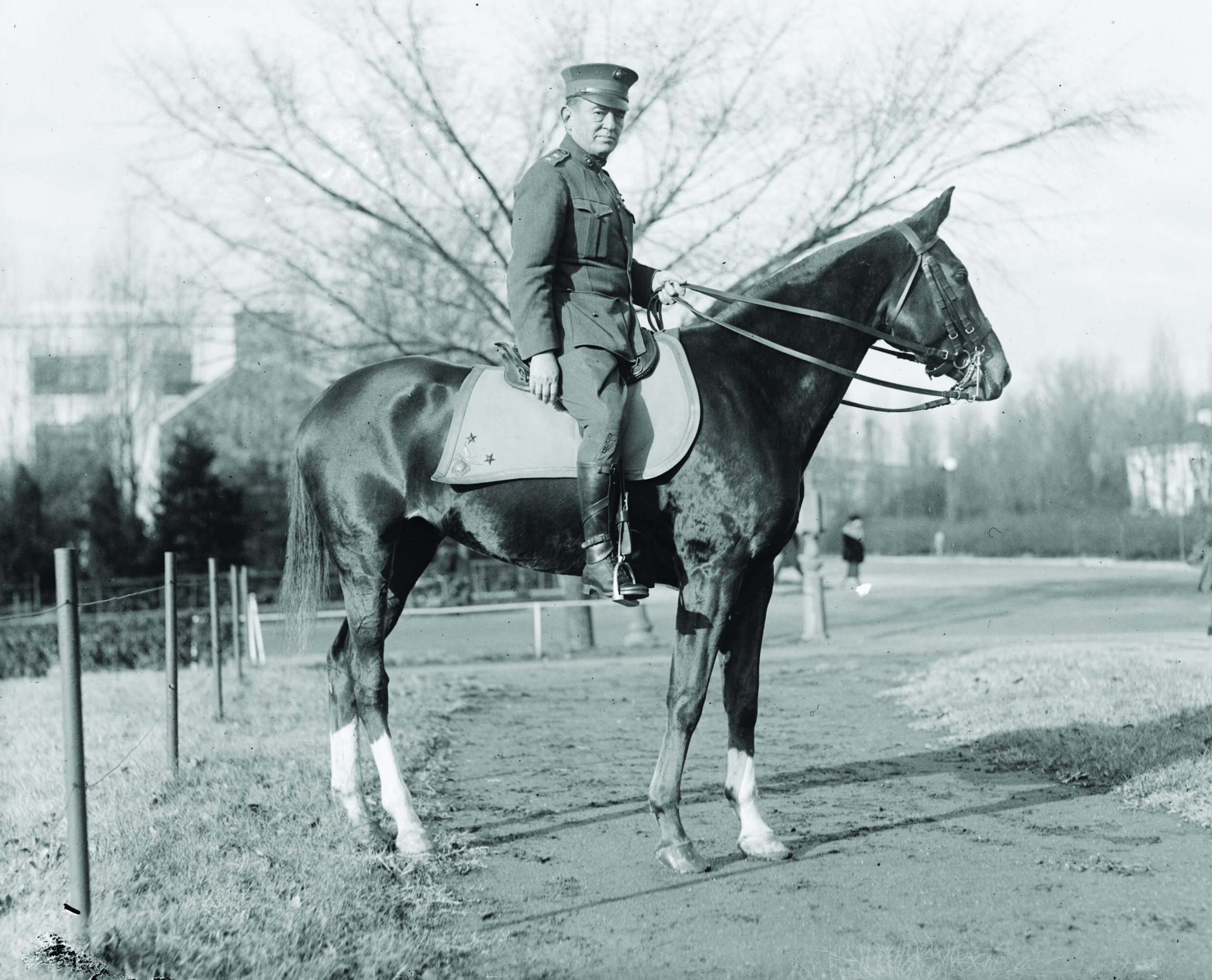

But John A. Lejeune, Major General Commandant from July 1920 to March 1929, may not be on many Marines’ short list of those Marines most responsible for transforming the Marine Corps into an amphibious assault force that had the capability of taking islands such as Tarawa and Iwo Jima in World War II. It is not that Marines are unfamiliar with Lejeune. Indeed, Lejeune, referred to as the “Greatest of All Leathernecks,” is well-known not only for his 1921 Birthday Message that is read annually but also for several other key accomplishments. He founded the Marine Corps Association in 1913, the Marine Corps League in 1923 and “created the Marine Corps Institute.” And, of course, Camp Lejeune is named after him. But most Marines may not be aware of Lejeune’s crucial role in setting the Marine Corps on the path to becoming the world’s premier amphibious assault force it would become, and the nation needed, in World War II.

In the first two decades of the 20th Century, the Marine Corps’ primary mission was to provide the Navy with an Advanced Base Force (ABF) to seize undefended or lightly defended islands in the Pacific as part of War Plan Orange (WPO). WPO was the Navy’s strategy for advancing across the Central Pacific to relieve the Philippines, fight and (presumably) win a modern-day Jutland against the Imperial Japanese Navy in the western Pacific; followed by blockading the Japanese Home Islands, leading to a complete United States victory. However, the Marine Corps Lejeune took over in 1920, while having the ABF in its force structure, was focused on the “Banana Wars,” not on supporting WPO. Lejeune would change that, ensuring the Marine Corps could survive as a separate service because it had a unique mission within the overall military establishment. Lejeune’s reforms and efforts during his nine-year tenure as Commandant laid the groundwork for the establishment of the Fleet Marine Force in 1933 and the publication of the “Tentative Manual for Landing Operations” in 1934; both of which undergirded the development of the capability to conduct opposed amphibious landings.

Background

Following the American victory in the Spanish-American War in 1898, the U.S. Navy needed bases between the newly acquired Philippine Islands and Hawaii to provide sheltered anchorages for their warships to use to replenish their coal supply if and when they were required to conduct a westward advance to relieve the archipelago from a Japanese blockade. “The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War: Its Theory, And Its Practice In The Pacific” by Jeter A. Isely and Dr. Philip A. Crowl, originally published in 1951 and republished by Pickle Partners Publishing in 2016, has this to say:

“Shortly after the conclusion of the Spanish-American War the attention of high naval planners was turned toward the problem of building a permanent force capable of seizing and holding advanced bases to be employed by the fleet in the prosecution of naval war in distant waters. Up to that time the duties of the Marine Corps had been limited largely to supplying marine detachments to vessels of the fleet and furnishing guards for navy yards, except during wartime when units of the Corps had actually participated in minor landings. The relatively easy victory over Spain did not conceal the fact that the fleet was incapable of sustained operations even in waters as close as those of Cuba, and the projection of American power far into the Pacific as a result of Commodore George Dewey’s victory at Manila Bay made the problem of acquiring bases even more acute … shortly after the war the General Board of the Navy, impressed by recent events … determined to set up a permanent advance-base force within the naval establishment. It was axiomatic that warships powered by steam were tied to their bases by the distance of their steaming radii and, since it was impracticable to maintain permanent bases in all parts of the world where the fleet might conceivably engage in action, it would be inevitably necessary in wartime to seize temporary bases against opposition if necessary. Defense of such bases once seized was an inseparable problem. The Marine Corps, an organization consisting of ground troops but with naval experience and under naval authority, was the obvious solution to the difficulty. Immediately tentative steps were taken to prepare the Corps for this new line of activity.”

Though preliminary steps were taken in 1901, the Marine Corps did not officially establish the Advanced Base Force until 1913. “Although the germs [sic] of later amphibious training my be found in this early advance base activity, it is clear that the great weight of the emphasis was not on offensive landing operations,” Isely and Crowl also wrote. “In fact, there is little resemblance between this early concept of the main function of the Marine Corps and its subsequent role as a military organization specially trained for amphibious assaults against enemy shores. Although in theory the advance-base force was supposed to be prepared to seize as well as defend bases, in practice all of the training concentrated on the defense.”

Even then, World War I and the “Banana Wars” conspired to keep the Advanced Base Force from being front and center in Marine Corps thinking. World War I was a seminal moment in the history of the Marine Corps because the Corps went from primarily “supplying Marine detachments to vessels of the fleet and furnishing guards for navy yards” as Isely and Crowl state, to gaining the ability to fight on the most modern and intense battlefield imaginable. The Marine Corps’ ability to field a brigade that could go toe-to-toe with the Germany Army (and its attendant “First to Fight” publicity) shifted the Marine Corps, both substantively and in the public’s mind, to moving beyond only providing ships’ detachments and being colonial infantry, to being an elite conventional fighting force; an image that would be cemented in World War II.

But the Banana Wars, which started before World War I, persisted during World War I and continued post-war, was the Marine Corps’ conscious primary focus when Lejeune became Commandant. What Lejeune foresaw and most didn’t, was that the colonial infantry role was not a viable mission for the Marine Corps long-term because opposition was growing against American intervention; which ultimately led to President Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor Policy” in 1933, “a policy of nonintervention in local affairs, applying specifically to Latin America.” He would be successful in his endeavor to wean the Marine Corps from the primacy of the colonial infantry role and put the Marine Corps on a trajectory to be an amphibious assault force, but only after overcoming deep-seated opposition within the Corps.

The Marine Corps’ Future:

Colonial Infantry or Advanced Base Force?

Joseph Simon, author of “The Greatest Leatherneck of All Leathernecks: John Archer Lejeune and the Making of the Modern Marine Corps,” writes “… by early 1920, the ABF—developed over the last 20 years—was in limbo, unable to support the Navy’s challenge in the western Pacific. In effect, the Marine Corps had returned to its old mission of providing troops for expeditionary and occupation duty in Haiti and Santo Domingo, acting as colonial infantry. Visionary Marines who supported the Navy’s new mission in War Plan Orange did not want to return to the past but did not have the power to establish amphibious assault as the [Corps’] new wartime mission.”

Marines had been fulfilling the colonial infantry role for the first two decades of the 20th century; indeed, “they had accumulated enough experience to write and publish “The Small Wars Manual” in 1921. (Author’s note: Originally called “The Strategy and Tactics of Small Wars” when published in 1921; renamed “Small War Operations” in 1935; then renamed the “Small Wars Manual” in the 1940 revision, the title by which it is known today.)

Many Marines enjoyed being deployed to Central and South America. They lived like kings while serving in exotic lands—or what Americans perceived to be exotic lands; the reality never seemed to live up to the fantasy. Fighting natives in the jungle promoted a swashbuckling image of Marines and was an inducement to young men who sought adventure. The Banana Wars provided great leadership opportunities for junior officers who would patrol for days with their only contact with higher headquarters being a radio carried on a pack animal that had to be assembled at the end of each day’s patrol. Marine officers had real-world opportunities to employ small unit tactics against the local insurgents; gaining experience that only comes with actual combat. According to one of his biographers, the legendary Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller looked back on his experience serving in Haiti in late 1919 and the early 1920s, as a watershed moment in his career:

“It was not until years later that Puller realized the full richness of his Haitian experience, and the value of its lessons in soldiering and hand-to-hand combat—he had fought 40 actions,” writes Burke Davis in “Marine! The Life of Chesty Puller.”

“He had not only been bloodied; the guerrilla combat had been almost continuous, most of it introduced by ambush on the trail. Puller had stood up well under this strain, and had come to trust his own physical prowess and ability to lead men under fire. He had discovered that native troops could become superb soldiers. He had developed his instinctive talent for using terrain in battle, and learned the lessons of jungle fighting … Despite his youth, he was one of the most seasoned combat officers in the Corps.”

The greatest and most senior champion for continuing to emphasize the colonial infantry role in the Marine Corps was an Old Corps legend—Brigadier General Smedley “Old Gimlet Eye” Butler. Butler owed his career advancement as much to his father, the highly influential Senator Thomas Butler, Chairman of the House Naval Affairs Committee, as much as to his service as a Marine fighting in the Banana Wars at Guantanamo Bay, the Philippines (three times), China, the Panamanian Isthmus, Nicaragua, Veracruz, Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

“[A] highly decorated Marine officer with little formal education beyond high school, [Butler] had won two Medals of Honor and believed in the egalitarian warrior ideal. Butler supported the [Corps’] old mission, was ambivalent about the amphibious mission, and believed that the Marine Corps performed better when separated from the Navy,” according to “The Greatest of All Leathernecks.”

The difference in Lejeune’s outlook and Butler’s is the result of their different experiences as senior officers. Like practically every other Marine, Lejeune fought in the Banana Wars, but he commanded a brigade and then a division in conventional, high-intensity combat on the Western Front. Butler’s career was in essence, from the beginning to the end, fighting in the Banana Wars except for deploying to France with the 13th Marines and then commanding the personnel depot at Brest at the very end of World War I. Butler’s focus was on the Marine Corps’ celebrated past that was going away and Lejeune’s focus was on positioning the Marine Corps for the future. If that was not enough, Butler who “believed that the Marine Corps performed better when separated from the Navy,” would have had trouble working in harness with the Navy to seize and defend advance bases where coordination between the two services was crucial. (Author’s note: Butler would later write “War is a Racket,” a book that repudiated his service in the Banana Wars.)

Fortunately, Butler was sidelined in the middle of Lejeune’s tenure as Commandant when Butler temporarily left active-duty service to be the director of the department of Public Safety for Philadelphia. While Butler wasn’t the only Marine who opposed Lejeune’s desire to move away from the colonial infantry role, he was the most senior and vocal. With him out of the way, Lejeune’s reforms could move forward unimpeded.

Lejeune’s Reforms

There are numerous things Lejeune did to improve conditions in the Marine Corps and, as Simon says, “to make the Marine Corps the most efficient military organization in the world.” Lejeune provided enlisted Marines with opportunities to learn a trade through vocational programs; reorganized recruiting service to ensure the Marine Corps was enlisting only the highest quality recruits, and worked diligently to economize and cut costs, earning Lejeune goodwill with Congress. Lejeune also “defined the relationship between officers and their men as ‘that of teacher and scholar’” and “promoted the Corps as an institution that uplifted young men’s lives mentally, physically, and morally.”

Several of Lejeune’s reforms directly led to the Marine Corps developing into the amphibious assault force it became after his tenure. While Lejeune did not remake the Marine Corps into the amphibious assault force that would become its hallmark, he laid the groundwork for that to be the case.

Advanced Base Force Becomes Marine Expeditionary Force

Perhaps the most important of Lejeune’s reforms was to rename the Advanced Base Force (ABF) the Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF). (Author’s note: In this context, “Marine Expeditionary Force” is a term meaning the available Marine forces on either the East and West Coasts available for deployment [one MEF on each coast]; not what Marines today know as an MEF.) As Simon writes in “The Greatest of All Leathernecks,” “ABF operations [were] of a defensive nature” and authors Jetek Isely and Philip Crowl state in “The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War” that “The advance-base force was in actuality little more than an embryo coastal artillery unit.” According to author Joseph Alexander in his book “Storm Landings: Epic Amphibious Battles in the Central Pacific,” the name change speaks to the offensive and more comprehensive mission of providing the fleet with “specially trained and equipped amphibious forces able to fight their way ashore.” “As of 1925 [a MEF] consisted of infantry, artillery, auxiliary troops such as engineers, signal, gas, tank and aviation units, all of them equipped and trained for service with the fleet.”

According to historian Alexander, Lejeune lobbied hard for the Navy to integrate the new MEF into the fleet.

“Lejeune understood that the future of the Marine Corps lay with the Navy and worked diligently to bring the Navy and Marine Corps closer together … Lejeune recommended to the Navy that the MEF become an integral part of the fleet, convinced the special board of policy of the Navy’s General Board that the MEF was essential to the fleet for conducting ship-to-shore operations, updated the pamphlet Joint Action of the Army and Navy (1927) to officially establish the [Corps’] role as the first to seize advanced bases in amphibious operations… .

“Again in 1926, Lejeune recommended that the MEF become a part of the fleet. He wrote to the CNO that ‘in order to clarify terminology, it is recommended that the Marine Expeditionary Force or Advanced Base Force,’ which would serve with the fleet … be designated, ‘Marine Corps Force, U.S. Fleet.’ ” Unfortunately, at this time the Navy was not prepared to recognize the MEF as part of the fleet.

“While Lejeune had only limited success in converting the Navy to his viewpoint, he succeeded in inspiring younger progressive leaders in the Marine Corps and Navy as to the importance of the new mission, a challenge that motivated these men to adopt and refine the mission of amphibious assault in the 1930s and 1940s.”

The MEF was the precursor to the Fleet Marine Force (FMF) and the transitional step between the defensive-oriented ABF and the offensive-oriented FMF capable of amphibious assaults against the most strongly fortified positions in World War II.

Marine Corps Schools

If the MEF provided the intermediate force structure step between the ABF and the FMF, Marine Corps Schools (MCS), established by Lejeune in 1921, would be the institution most responsible for providing the intellectual underpinning for the Marine Corps’ ability to assume the amphibious assault role as its own. According to Alexander, “one of Lejeune’s greatest and most enduring contributions to the Corps was the establishment of the MCS. As Commandant, Lejeune saw a great need for more in-depth military training for officers in order to modernize the Corps … Based on his own experience, Lejeune knew that the average Marine officer received minimal formal military training.

However, in the beginning, MCS did not focus on amphibious warfare. According to Alexander, Lejeune’s “original intent in developing the MCS in the early 1920s was to utilize his experiences in the world war to teach new officers and recruits infantry tactics and how to fight a modern war using a combined-arms approach. This approach stressed greater firepower by combining infantry, artillery, tanks, and aircraft in the attack against a powerful enemy. Although this focus remained until the mid-1920s, it later became clear that Lejeune wanted to use the combined-arms approach for amphibious operations.”

As stated in “The Greatest of All Leathernecks” by Simon, the original focus of MCS was to teach “how to fight a modern war.” But after Marine officers learned the basics of combined arms on land, the MCS would transition to focusing on the amphibious assault.

“Lessons learned from the study of Gallipoli became part of the Marine Corps—Navy maneuvers of 1924 and 1925. In the early 1930s, Brigadier General James C. Breckinridge, head of the MCS, significantly increased the study of the failed Dardanelles operations. The Gallipoli amphibious disaster became a key part in the study of landing operations and helped develop the landmark ‘Tentative Landing Manual’ of 1934.”

Usually, the establishment of the MEF in 1933 and the publication of “Tentative Landing Operations Manual” in 1934, are considered separate events. But there was a relationship between them that is often overlooked. Colonel Robert D. Heinl Jr., USMC (Ret) says it best in his essay “The U.S. Marine Corps: Author of Modern Amphibious Warfare” in “amphibious thinkers produced the Fleet Marine Force; this unique unit in turn gave body and substance to the doctrinal theories of its creators; and the interaction of the two combined in substantial measure to make possible the victorious beachheads of World War Two.”

Other Reforms

There were three other reforms Lejeune did that still serve the Marine Corps today. According to Simon, based upon Lejeune’s experience in command of the Army’s 2nd Division in France, he adopted the French Army’s G-1/G-2/G-3/G-4 staff system for “independent field commands of brigade size or larger” streamlining and making staff functions more efficient.

Second, Simon writes that “Lejeune pioneered the modern use of air power in the Caribbean occupations … For the first time, Marine aircraft provided direct air support to small infantry units on the ground fighting rebels in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua.” Lastly, the Butler-directed reenactments of Civil War battles in the early 1920s, would on the face of it, be nothing more than “a reproduction in pageantry form of the Civil War battle at that place, as little would be gained by either officers or men as regards lessons of a military nature.” While true to a greater or lesser extent, especially early on, Lejeune saw these reenactments as valuable training opportunities. They got the Marines into the field under wartime conditions and tested equipment “under service conditions.”

Conclusion

During his nine-year tenure as Major General Commandant, Lejeune did not transform the Marine Corps from a colonial infantry force into an amphibious assault force. Lejeune set the Corps on the trajectory to becoming the world’s premier amphibious force by moving the Marine Corps’ focus away from the colonial infantry role; changing the name of the ABF to MEF and expanding its focus; and establishing MCS, which would in a few short years after Lejeune’s tenure, write the “Tentative Landing Operations Manual.”

As Simon writes in “The Greatest Leatherneck of All”: “Lejeune’s greatest legacy to the Marine Corps of the 1930s—and even to the Corps of today—was his capability as a strategic leader in providing direction, purpose, and identity. Lejeune could envision the near future and… [could] convince the Navy Department and the Joint Army and Navy Board that his vision for the Marine Corps was realistic. Lejeune established for the Marines “their own separate and very distinct culture and identity.” Perhaps Lejeune’s greatest strength was his ability to anticipate future conflicts and prepare the corps to successfully deal with them—specifically, a likely war in the Pacific. Lejeune made the visionary decisions that changed the culture of the Marine Corps and laid the foundation for the development of amphibious warfare that established the standards realized during World War II and after.”

Major General Commandant John Archer Lejeune was indeed, “The Greatest of all Leathernecks.”

Author’s bio: Maj Skip Crawley, USMCR (Ret), was an infantry officer in 1st Battalion, 7th Marines during Desert Shield/Desert Storm. He has had numerous book reviews published in Marine Corps Gazette. This is his first article for Leatherneck.