Ichabod Crane, the Marine

By: Edwin TurnbladhPosted on October 28, 2024

Editor’s note: This story was originally published in the November 1959 issue of Leatherneck Magazine.

Anyone digging into Marine Corps archives of the years just before the War of 1812 might be startled to see there on the rolls of officers the name Ichabod Crane-perhaps one of the best known names in American literature. The discovery is particularly interesting because Washington Irving was then beginning to write, and it was just seven years after Lieutenant Crane resigned from the Marine Corps that “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” was published-date 1819.

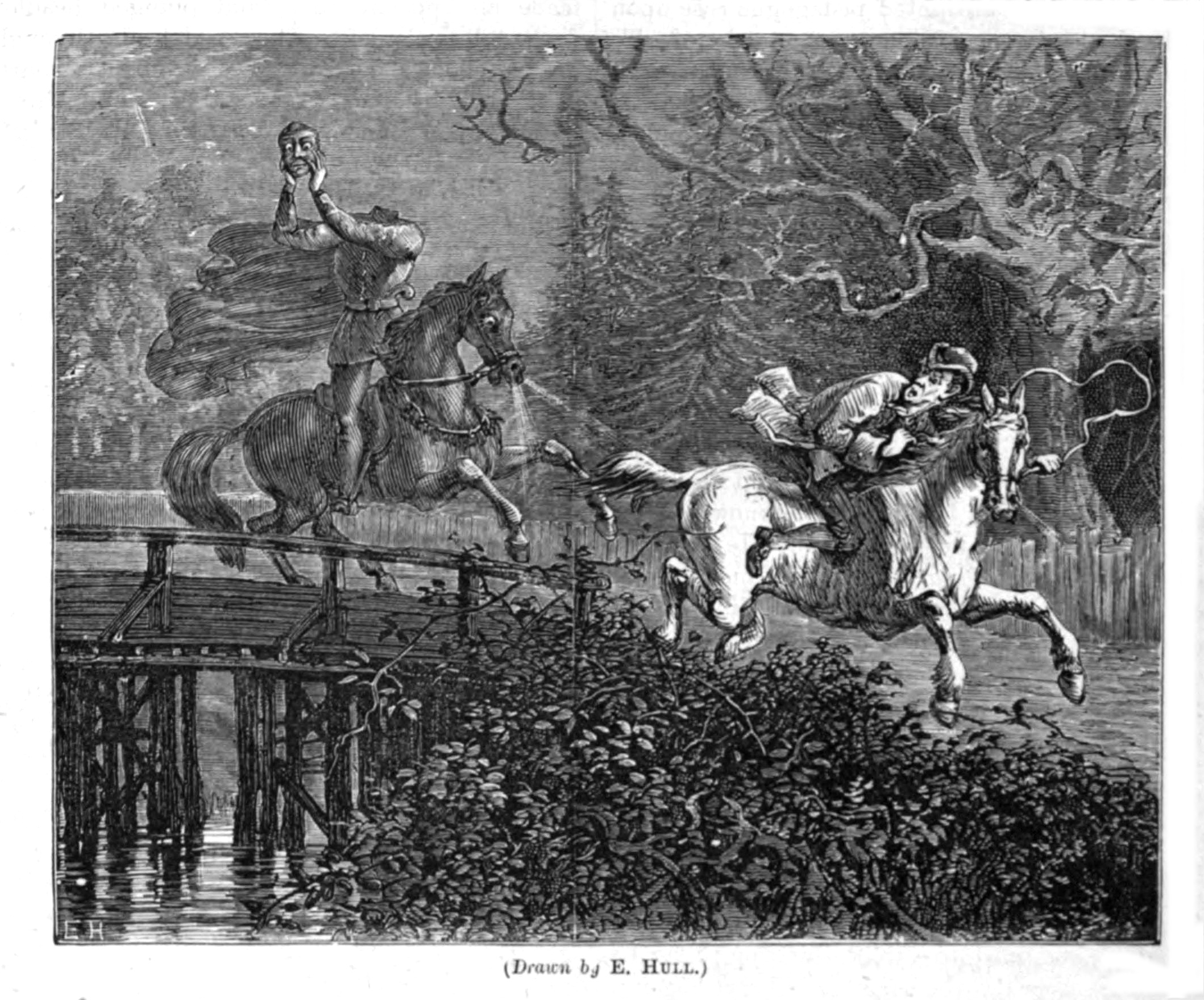

The beloved story offers various local guesses as to what became of the schoolmaster after the hapless fellow’s encounter with the “headless horseman” and subsequent disappearance. Different villagers said he “had changed his quarters to a distant part of the country; had kept school and studied law at the same time; had been admitted to the bar, turned politician, electioneered, written for the newspapers, and finally had been made a justice of the Ten Pound Court.”

Not one of the villagers of Sleepy Hollow said that perhaps Ichabod had gone and joined the Marines. He may, indeed, have tried but been sent kiting by a supply sergeant at wit’s end, attempting to furnish a uniform. For Ichabod, you will recall, was “exceedingly lank, with narrow shoulders, long arms and legs, hands that dangled a mile out of his sleeves, feet that might have served for shovels.”

At any rate, it is logical today to speculate that Washington Irving did take the name for the village school-master from a Lieutenant Ichabod B. Crane of the Marine Corps, having most certainly encountered the name not long before he wrote the tale, and, what is more, having quite probably met the officer. The author’s fancy may have been caught by the name. The schoolmaster was a period piece, who merely needed a name. The model was not uncommon.

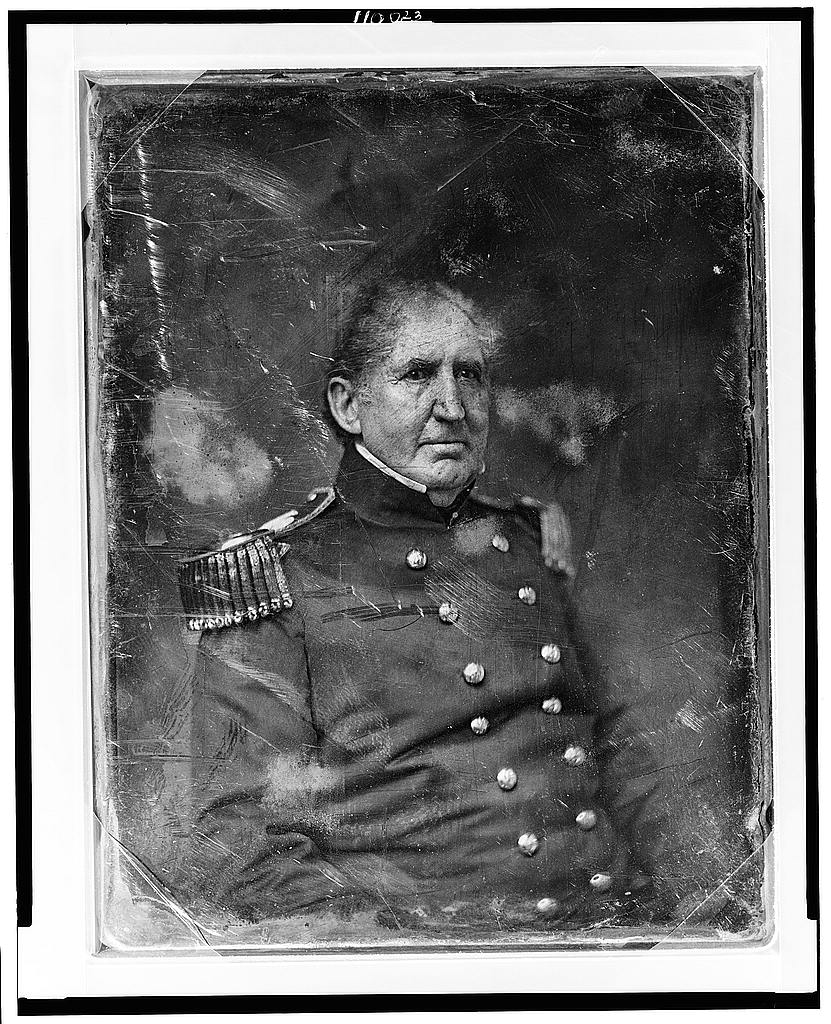

Ichabod B. Crane was a native of Elizabethtown (now Elizabeth) New Jersey, a descendant of a first settler of the town. He was appointed a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps on 26 January, 1809, from Irving’s State of New York, receiving $25 a month and subsistence. Ichabod’s father, General William Crane, had been a Revolutionary artilleryman, wounded at the attack on Quebec, but surviving to serve as Major General of New Jersey Militia during the War of 1812. Ichabod’s brother, William Montgomery Crane, entered the Navy as a midshipman in May, 1799, serving on the United States, becoming a lieutenant in 1803, and a commander by 1813.

Ichabod, upon joining the Marine Corps, was assigned in February, 1809, to command the Marine detachment on board the United States, which was a 44-gun frigate, a sister ship to Old Ironsides, and herself affectionately termed the “Old Waggon.” The detachment was authorized to number two sergeants, two corporals, two musics (a fifer and a drummer), and 50 privates, but it was seldom near that strength. Lt Crane’s routine experience as commander of the seagoing Marines may well have consisted partly of settling arguments between Marines and Sailors of that rough period. Your “rights . . . are sometimes liable to be infringed on.” warned Lieutenant Archibald Hender-son. later a Marine Corps Commandant. All through the 19th century a Marine detachment on board a ship was known as the Marine Guard. In peacetime they composed a disciplinary force at sea, deterring mutiny—”the bulwark between the cabin and the forecastle.”

Lt Crane continued on the United States until December, 1810. when he was detached to Marine Corps Headquarters at Washington. In March, 1812, he was due to relieve a Captain Williams at a Florida post, but a change of plans kept him at Washington.

In May, 1810, Captain Stephen Decatur, a close friend of Washington Irving, was ordered to command the United States. Thus, for almost a year. Lt Crane had served under living’s friend-in charge of the Marines on that ship.

Decatur and Irving once roomed together in New York, and through the years, before Irving went to England (1815) the two men saw each other often. The author could, therefore, well have been introduced to Decatur’s Marine officer. Decatur may at least have mentioned the man.

Irving possessed what William Cullen Bryant called a ”frolicsome fancy” -certainly exhibited in his stories of Dutch New York. He delighted in naming literary characters after persons he knew or heard of. In 1809 he wrote Diedrich Knickerbocker’s humorous history of New York. In it he freely employed old Dutch family names—“but I did not dream of offense,” said the amiable Irving.

Irving wrote “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” while on a visit to England. The story, like others of the Sketch Book series, appeared in America in 1819 under Irving’s pen name, Geoffrey Crayon. Few persons, either in America or abroad, ever did learn who the real author was. Many, especially in Great Britain, thought it was Sir Walter Scott, the literary lion of the hour and a most admiring friend of Irving.

The Sketch Book series became at once popular, selling rapidly, and Ichabod B. Crane must surely have either read of the schoolmaster or had his attention called to the coincidence of names. Whether he knew, however, that “Geoffrey Crayon” was actually Decatur’s friend, Irving, is less presumable. By that date, Crane was a major in the Army. After resigning from the Marine Corps on April 28, 1812, he had accepted a captaincy from the Army. It was the military which engrossed the life of Ichabod B. Crane. He was not a horseman-nor did he ever write, like Washington Irving or his own descendant, Stephen Crane, the New Jersey author of the Civil War story, “The Red Badge of Courage.” Lt Crane of the Marine Corps would have been interested to foresee that Stephen Crane, as a war correspondent, covered a Marine landing in 1898 at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Washington Irving’s interest in the Navy must surely have included the Marine Corps, which then, as today, was a part of the Navy Department. The author became well acquainted with Charles Nicholas of Philadelphia, a son of Samuel Nicholas, the first Marine officer appointed by the Continental Congress after it voted for two battalions of Marines on 10 November 1775, the historic birthday of the Marine Corps.

Although Irving showed a zest for naval exploits and affairs, his role was essentially that of a detached bystander, rather than a participant. He declined two offers of a post in the Navy Department. In 1818, Commodore Decatur was serving on the Board of Navy Commissioners at Washington, a sort of directorate composed mainly of ex-naval heroes. So Decatur had no difficulty obtaining the job of first clerk in the Navy Department for his good friend Irving but entirely unsolicited by the author, who was then in Europe.

William, Washington’s brother, then a Congressman, wrote enthusiastically to the author: “Commodore Decatur informs me that he had made such arrangements, and such steps would further be made by the Navy Board, as that you will be able to obtain the office of first clerk in the Navy Department, which is similar to that of under-secretary in England. The salary is equal to $2400 per annum, which, as the Commodore says, is sufficient to enable you to live in Washington like a prince.”

But Irving was indifferent to so bright a prospect. He turned down the job, explaining that it meant a “routine of duties” which would “prevent my atending to literary pursuits”—although William had emphasized that he could still do that while holding the clerkship. Practical William was concerned about the declining family fortunes. Their long-time hardware business had just gone through bankruptcy, and young Washington, then 35 years old, was not yet the prosperous author. To brother William, as well as to Decatur, the Navy clerkship seemed a profitable and secure plum until Washington’s literary talents were more appreciated.

In 1838, President Van Buren, a personal friend, like Decatur, wanted Irving to become Secretary of the Navy. But then, as 20 years before, and despite a permanent interest in the Navy, Irving still did not care for a desk job at the Department. In declining this time, he said that “a short career of public life at Washington . . . would render me mentally and physically a perfect wreck.”

During subsequent years Irving enjoyed the life of a celebrated author at his home, “Sunnyside,” near Tarrytown, New York. Meanwhile, at some Army post, Crane was serving as a colonel of artillery. He died in 1857, just two years before Irving, on Staten Island, New York.

Ichabod B. Crane’s Marine Corps service was just a brief three years. It provided no occasion where he could win fame in the heroic annals of the Corps. Nor did the Army supply a chance for remembered glory. Yet, as men sometimes do, he achieved a quite unexpected kind of immortality. Because of Washington Irving, his name wells forever on the pages of American literature.