History of the Marine Gunner: Unearthing the Roots of This Misunderstood Distinction

By: Ed NevgloskiPosted on April 15, 2024

Executive Editor’s note: This article explores the origins and inception of the Marine gunner and is the cornerstone of an upcoming series in Leatherneck tracing its often-mistaken evolution. Written using official Marine Corps history, it draws extensively from the documents and personnel records stored at the U.S. National Personnel Records Center and National Archives in Washington, D.C., and St. Louis, Mo., and at the Marine Corps Archives in Quantico, Va.

One of the Marine Corps’ three original warrant officer ranks, the Marine gunner is arguably the most coveted in the service’s nearly 250-year history. It is also the most misunderstood. In more than a century since its inception in 1916, the Marine Corps has abolished and reinstated the Marine gunner on three occasions. The Marine Corps eliminated the rank and in its distinctive “bursting bomb” insignia first in 1943, only to restore both in 1956 as a designation for non-technical warrant officers. After discontinuing both in 1959 and restoring and revising their use in 1964 as a designation limited to warrant officers in combat arms military occupational specialties, the Marine Corps dissolved both again in 1974. Finally, in 1989, the title and insignia returned for warrant officers assigned as crew-served infantry weapons officers, where they still reside. Unfortunately, with no official written history to reference, the Marine gunner has become an institutional treasure cloaked in confusion.

Naval Origins

To understand the evolution of the Marine gunner is to understand the origins and historical background of the warrant officer itself. The earliest known warrant officers date back to around 1040 in England. According to British naval historian Nicholas Roland, to compensate for the lack of experienced seamanship on the part of the English noblemen and, later, the army officers placed in command of maritime expeditions, skilled civilian journeymen accompanied the ships’ crews to supervise its more technical functions. Hundreds of years later this practice continued to allow commissioned naval line officers to focus on the tactics of fighting a ship and not its operation. This custom extended to providing persistent crew training and equipment maintenance during and between expeditions.

As a reward for an acumen uncommon among its line officers who received their authorities from the king or queen of England, the Royal Navy’s Board of Admiralty issued to select journeymen warrants granting them what naval historian Russell Borghere defined as permanent or “standing” officer status while onboard a ship. An element of the agreement between the board and these warranted or “warrant” officers was they remain with a ship from its construction to its decommissioning, unlike line officers who might transfer to another ship following an expedition. Although an appointment held less authority than a commission, it offered higher pay and seniority over the ranking enlisted Sailor. In time, warrant officers proved to be a necessary and vital link between a ship’s crew and its commissioned officers and the ship’s captain.

The Royal Navy’s first warrant officer ranks (and their corresponding departmental functions and titles) were the boatswain and the master. The lengthier expeditions of the 15th and 16th centuries brought about new functional specialties requiring a warranted officer. The sailmaker, carpenter, surgeon and purser were but a few additions. In response to advances in military engineering, the Royal Navy replaced its vintage cannons with large artillery pieces on their ships of the line in 1571. The change required extensive and continuous crew training on operating procedures, supervised maintenance on the ship’s guns and gunnery equipment, and preservation of the gunpowder, ammunition, cartridges and gunlocks stored inside a ship’s magazines. The Admiralty Board addressed the transition from cannons to artillery pieces by adding veteran army artillerymen to ships’ crews and warranting them to the rank of naval gunnery officer or “gunner.”

A popular Scandinavian term (and name) meaning “one who battles,” artillerymen and grenadiers in several European armies adopted gunner as a title to distinguish themselves from line soldiers. Still today, the Royal Army artillery’s equivalent to the American rank of private is gunner. Royal Navy artillerymen adopted the title for the junior-most seaman and even elevated its significance by using it as the gunnery warrant officer’s official rank and title. To distinguish between the two, commissioned officers and seamen refer to the gunnery warrant officer as “the gunner” to emphasize his singularity, expertise, and authority—and as a matter of prestige.

Warrant officers in American military history date to October 1775, when the Second Continental Congress authorized General George Washington to assemble a colonial fleet to make war with England. Washington used the Royal Navy as the model from which he organized his fleet, including the practice of warranting standing officers “under the rank of third lieutenant” in accordance with Congress’ Naval Committee directives. Among Washington’s warrant officers were gunners. When the new U.S. Congress established a navy in 1794, gunners were again one of its seven standing officers and performed the same duties as their Royal Navy predecessors. The U.S. Navy further institutionalized its warrant officers after the American Civil War by extending appointments to its most experienced enlisted Sailors demonstrating exceptional technical skill and leadership potential.

Warrant officer uniforms in the U.S. Navy were similar in every way to a commissioned officer’s and distinguished only by a half-inch long by quarter-inch wide blue and gold cloth stripe on the uniform cap beginning in 1853. Beginning in 1864, select English, French, and Italian infantry and artillery units incorporated a “flaming grenade” insignia for wear on their helmets and coasts as a mark of distinction. In 1883, when the Navy added insignia devices for each warrant specialty, officials approved for wear on the gunner’s frock coat collar and on the collar of the blue service coat a version of the flaming grenade insignia. The Navy went as far as to distinguish between gunners with 20 years in grade, who wore an insignia cast in silver, from those with less than 20 years, who wore a gold insignia. Overseers of the naval uniform regulations added a blue and gold stripe and the flaming shell to the coat sleeves in 1899.

That same year, the Navy added a commissioned warrant rank to offer its senior warrant officers an opportunity to advance and take on positions of greater authority. As an aside, the Admiralty Board in England warranted the rank of gunnery sergeant major to that of a Royal Marine gunner, an equivalent rank to the Royal Navy’s gunnery warrant officer in July 1910. The Royal Marines adopted the ‘flaming shell’ as well.

Search for a Mission: The Advance Base Force

The Spanish-American War arguably marks the birth of the modern Marine Corps and the end of the service’s search for a mission. Previously, Marines were primarily ships’ guards, provided physical security at naval stations and American embassies around the world, and formed small landing parties for minor seaborne raids and assaults against enemy coastal defenses. This changed for good in April 1898 when Secretary of the Navy John D. Long directed Marine Corps Commandant Major General Charles Heywood to organize a battalion for duty with the Navy’s North Atlantic Squadron. By June 10, five infantry companies and an artillery battery under Lieutenant Colonel Robert W. Huntington’s 1st Marine Battalion was ashore at Guantanamo Bay where it established an expeditionary base for operations against Spanish forces a mere two months after America declared war on Spain.

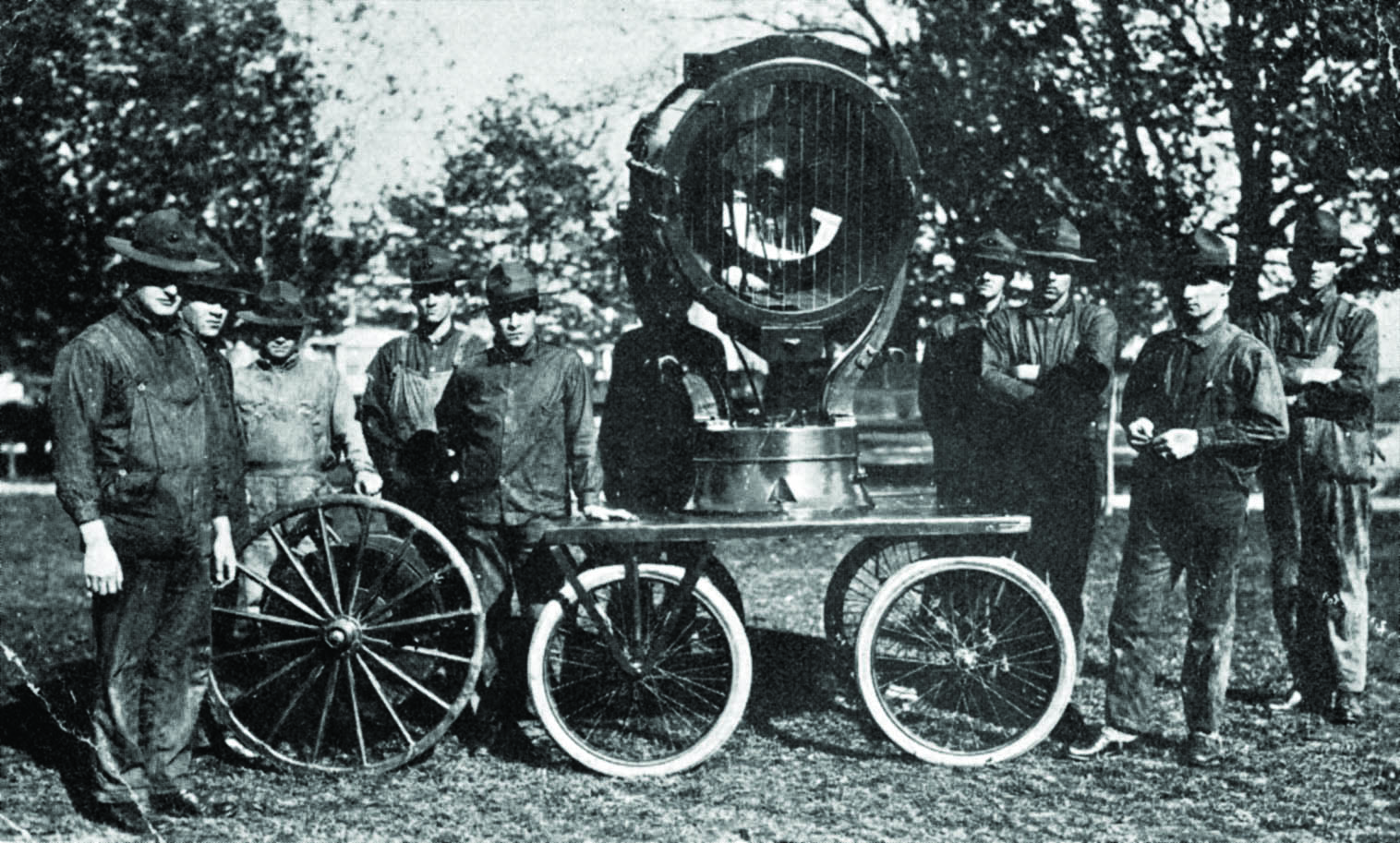

Although the Guantanamo landing was not the Marine Corps’ first, it was its first attempt at establishing an expeditionary base comprising fixed defensive positions with integrated advanced weaponry and equipment like medium machine guns, light artillery, naval gunfire, searchlights and signals communications. The expeditionary or advance base concept changed significantly how the Marine Corps viewed its role in modern naval warfare and how technological advances impacted its success. It would also become the genesis of its creation of a warrant officer structure, namely that of the Marine gunner.

The war against Spain was a byproduct of a doctrine established in 1823 by President James Monroe to prevent European powers from encroaching upon American interests in the Western Hemisphere. Cuba’s bid for independence from Spain was the first real test of the Monroe Doctrine. Control over the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico and Cuba in the Caribbean and Hawaii, Guam and the Philippines in the Pacific at war’s end meant the U.S. now had to develop an approach to defending these territories from a strengthening German and Japanese hegemony in both regions. An advisory committee, the General Board of the Navy, recommended to Secretary Long that he assign Marines with “emplaced naval guns, high angle artillery, machine guns, infantry and water and land minefields” to the mission.

Between 1901 and 1913, the Marine Corps tested and evaluated the advance base concept. In February 1914, the commanding officer of the 1st Advance Base Brigade, Colonel George Barnett, assumed the Marine Corps Commandancy.

Among his chief concerns was managing the service’s commitment to the concept while at the same time providing Marines for protracted naval expeditions to Mexico, Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Believing also that America and the Marine Corps would enter the war in Europe, Barnett wanted Marines organized into larger tactical formations equipped with the latest battlefield technologies. To prepare for potential war, the Navy’s number of warrant officers, ranging normally between 200 and 300, rose to more than 1,000 in 1916 after the House of Representatives’ Committee on Naval Affairs authorized a 34 percent end strength increase. In much the same way the new Navy Secretary, Josephus Daniels, was expanding and modernizing the Navy to counter Germany and Japan, Barnett petitioned he do the same for the Marine Corps.

The Case for Gunners in the Marine Corps

Essential to modernizing the service and ensuring its mission success, in Barnett’s judgement, was the continued retention of experienced senior enlisted Marines and getting the most from their leadership and their proficiency with the latest military technologies, particularly advance base force weapons and equipment. In an Oct. 11, 1915, memorandum drafted in advance of his annual testimony before the House of Representatives’ Committee on Naval Affairs, Barnett wrote that the “reenlisted noncommissioned officers constitute, next to the officer, the most important part of any military organization.” As for their specific role, Barnett conceived that since “the services of warrant officers are just as badly needed in the Marine Corps as they are in the Navy,” making them officers might be the best approach to maximizing their continued service.

Barnett conveyed the same to the House Naval Committee on Feb. 29, 1916. Describing the most recent expeditions as “naval mission[s]” contributing directly to the “highly technical” advance base concept, Barnett stressed that integral to the concept’s continued success hinged upon maximizing experienced noncommissioned officers skilled in caring for and maintaining “the heavy guns, submarine mines, searchlights, [and] field wireless stations” and to serve as “infantry, as engineers, and as aviators, etc.” Their continued service in one of the recommended two “grades of warrant officers,” Barnett offered, was not only beneficial to the Marine Corps but “an act of simple justice to the senior noncommissioned officers” who “perform the most responsible kinds of duty in an extremely efficient manner.” After his testimony, Barnett took questions from committee members. As to what he intended to call these warrant officers, he replied, “We would call them marine gunners and quartermaster clerks.”

News that the U.S. Senate had approved the committee’s House Resolution 15947 reached Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels in early August, prompting Barnett’s staff to draft Marine Corps Order (MCO) 27 on Aug. 18, establishing the service’s first warrant officer screening and appointment process. President Woodrow Wilson signed the Naval Appropriations Act of 1916 into law on Aug. 29, specifying that “the warrant officer grades of [M]arine gunner and quartermaster clerk shall be created, and that 20 [M]arine gunners and 20 [M]arine quartermaster clerks shall be appointed from the noncommissioned officers of the Corps.” These were to be the only permanent appointments, though the act prohibited neither Barnett from recommending nor Daniels from approving any number of temporary appointments on an as-needed basis.

In accordance with Article 1645 of the Navy Regulations, MCO 27 directed that only after being “satisfied from their records” that applicants were “mentally, morally, and physically qualified” could Barnett recommend a Marine for appointment. The mandatory first step in assessing the applicant’s moral aptitude was through an interview with a commanding officer. Measuring the applicant’s mental fitness would come through a battery of written academic and military-specific tests. Those applicants scoring high enough on the written exams would undergo a thorough medical screening.

Barnett organized an examination board comprised of four Marine officers whose responsibility was to track the process and then recommend to him the names of 11 noncommissioned officers to serve as technical specialists and another nine for non-technical or ‘general duty’ leadership positions requiring Marine officers. The fields and specific areas of expertise necessitating a “warrant gunner” were:

• Main Battery (Advance Base): ordnance and gunnery, fire control, handling heavy weights, and boat seamanship.

• Submarine Mines: use, care, and preservation of submarine mines; fire control; electricity; and boat seamanship.

• Field Artillery: field artillery and drill regulations, fire control, field service regulations.

• Searchlights: use, care, and preservation of portable searchlights; electricity; and gasoline engines.

• Signals: use, care, and preservation of various forms of visual signal, telegraph, telephone, and wireless outfits; electricity; and gasoline engines.

• Engineering: military field engineering; military field topography; demolitions; explosions; construction of bridges, roads, etc.; and field service regulations.

• Aviation: use, care, and preservation of aeroplanes; dirigible balloons; balloon kites; captive balloons; gasoline engines, and military topography (especially with reference to terrain observation from air machines).

• Machine Guns: use, care, and preservation of the various types of machine guns; machine gun tactics; and field service regulations.

• General Duties: firing regulations, field service regulations, and administration.

Getting the Word Out

For years the Marine Corps kept its personnel and the public informed through announcements in national and local newspapers. Promotions, assignments, retirements and deaths, and news of interest all appeared in print. Two additional sources were the Recruiter’s Bulletin, published by the Marine Corps Recruiting Bureau, and the Marine Corps Association’s Marine Corps Gazette (and Leatherneck beginning in 1917).

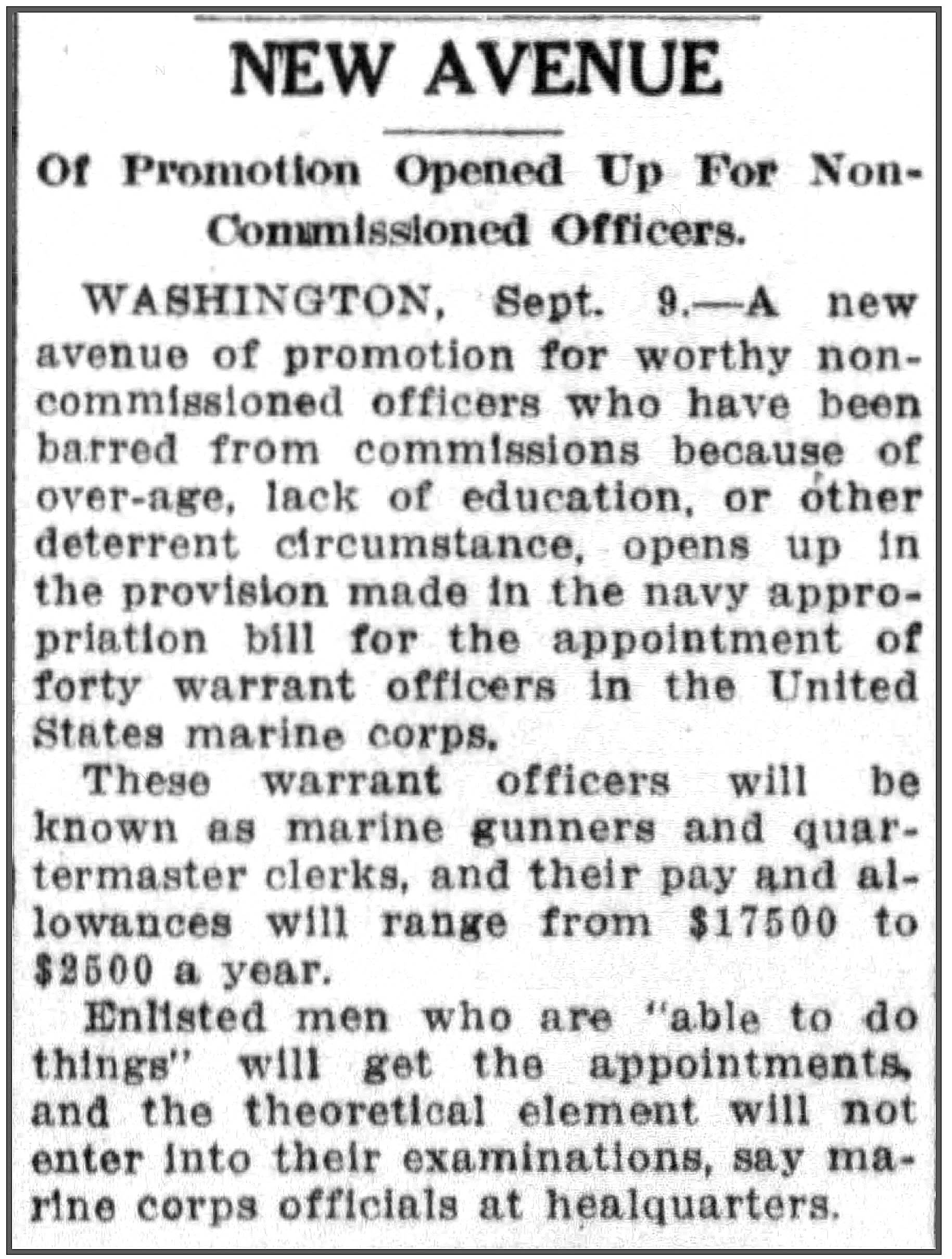

As early as Sept. 9, Ohio’s Dayton Daily News reported the Naval Act’s details. One article in particular spoke to an advancement opportunity for noncommissioned officers whose “over age, lack of education, and other deterrent circumstance” precluded them from the traditional path to becoming Marine Corps officers. The article went on to explain that “these warrant officers will be known as [M]arine gunners and quartermaster clerks and their pay and allowances will range from $1,250 to $2,000 a year.” An unnamed Headquarters Marine Corps official interviewed emphasized that the service was seeking worthy enlisted men over 30 years of age and simply “who are able to do things.”

In the weeks and months ahead, newspapers like The Washington Post kept Marines apprised during each step in the screening process. On Dec. 3, the Post announced that a board “engaged at the headquarters of the marine corps in examining recommendations of the commanding officers and other papers pertaining to enlisted men” who seek to become Marine gunners.

The Marine Examining Board

The phased screening process laid out by MCO 27 began when an interested noncommissioned officer initiated his intentions to apply for an appointment and culminated with Barnett forwarding the names of selectees to Secretary Daniels for appointment. Each applicant first had to complete an interview with his commanding officer (field or post command and naval command) to obtain a command endorsement. Endorsements had to attest to the applicant’s moral fitness to perform the duties of a Marine officer. Applicants then submitted handwritten requests to the board to take the required medical and professional exams. The interview results, command endorsement and hand-written request had to be sent to Headquarters Marine Corps in Washington, D.C., by early December, when the next phase of the screening was to begin.

In between the endorsement interviews and the final selection were the actions of the “Board for Recommendation of Marine Gunners and Quartermaster Clerks,” known also as the Marine Examining Board. Barnett issued a letter on Nov. 20 directing Brigadier General John A. Lejeune to preside over the board and the second screening step. Present at his House Naval Committee testimony, Lejeune understood what Barnett desired in warrant officers. Joining him as board members were Colonel Charles G. Long, Lieutenant Colonel William B. Lemly and Major Harry R. Lay. Their primary task after reviewing applications and applicant service records was “recommending to the Major General Commandant the names of noncommissioned officers” to take the medical and professional exams.

According to its official signed report, the board met daily between Nov. 25 and Dec. 5 and reviewed applications from 117 noncommissioned officers who applied for Marine gunner. They selected 54 to advance to the third phase, which was the professional exams. In preparation, the board solicited from subject matter experts in each field and specialty exam questions and answers as well as to determine how the professional exams were to be administered. As the questions and answers arrived, the board mailed them to some 16 separate locations, 11 of which were naval stations along with three ships, and, finally, to the Marine commands deployed to Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

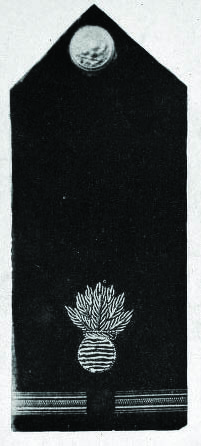

As the screening process and exam preparation played out, questions as to what the Marine gunner’s rank insignia would consist of surfaced. Barnett’s choice was a chased spherical shell three-fourths inch in diameter similar to the Navy’s device with the flame five-eighths inch high. The 1917 revision of the 1912 Marine Corps Uniform Regulations dictated that the Marine warrant officer’s uniform requirement “will be the same as prescribed for a second lieutenant, but that the Marine Corps emblem and the sword knot will not be worn.” In lieu of the emblem would be an insignia of “silver on the collar of the undress and white undress and of bronze on the summer field and winter field coats and on the shoulder straps of the overcoat and on the collar of the flannel shirt when the coat is not worn.” Marines would soon after refer to the insignia as a “bursting bomb.”

The Washington Post announced on Dec. 17 that the Marine Examining Board had issued notices to selected applicants to report to various naval stations within the continental U.S. on Jan. 29, 1917 for the medical exam and, if cleared for duty, to take the week-long professional exam. Those overseas were to return to America at once if commanding officers could not arrange an adequate exam facility. A memorandum released by the board directed that the professional exam period run from Jan. 31 to Feb. 7, with at least one test administered each day except Sunday.

The Professional Exam

Three components made up the professional exam required for Marine gunners with a maximum of 100 total points. The first measured the applicant’s aptitude in composition, reading, writing and spelling as well as basic arithmetic, with the second testing the general knowledge of the Army’s Infantry Drill Regulations. The material covered in these first two components were identical and subject to the same grading values with a maximum possible combined score of 30 points.

The third component challenged the applicant’s advanced knowledge and proficiency in their identified fields and specialties. Depending on the field and specialty, an applicant could expect a different number of tests, though each required the interpretation and drafting of schematics and calculations to answer the many scenario-based questions taken from actual events related to the areas of expertise highlighted in MCO 27. Each area had specific grading values with a maximum possible combined score of 30 points. Testing for aviation and engineering applicants covered six separate specialty areas with main battery and submarine mines tests covering four different areas. Field artillery, searchlights, signals, machine guns and general duties applicants underwent testing in only three specific areas.

The remaining 40 points would come from the board’s review of each applicant’s official service record, including the results of their commanding officer’s interview. The board considered recommendations from past commanding officers or officers in charge, expeditionary service, marksmanship, and military and civilian education and training, as well. Applicants had to obtain an overall average of 75 percent to undergo further consideration.

Conclusion

On March 16, Barnett received from Lejeune the board’s report, ranking highest to lowest in order of exam averages the names of 20 noncommissioned officers. Barnett signed and forwarded the list to Secretary Daniels, who issued the signed appointment letters on March 24. The board then sent telegrams to the commands of selectees and released the names to the Recruiter’s Bulletin and news outlets. The Washington Evening Star was one of the first papers to reveal the names on April 2. In the hometowns of those selected, local papers published more personalized announcements. On April 4, the Daily News in Lebanon, Pa., announced “Lebanon Boy Gains Distinction in the United States Marine Corps.” The following day Democrat and Chronicle in Rochester, New York, bragged “Rochester Man Goes Up In The Marine Corps: Promoted After Passing Competitive Examination.” Across the country, towns celebrated those “rising from the ranks.”

The first 20 noncommissioned officers proudly pinned the bursting bomb insignia on their stock collars for the first time in Marine Corps history only days after Daniels signed their appointment letters. Several received orders to the 1st Advance Force Brigade. Those already overseas on expeditionary duty in Haiti and the Dominican Republic remained with their commands and assumed various leadership roles. Others boarded transport carriers at Quantico for movement across the Atlantic to France; some would not come home. All, however, played a part in fostering the reputation retired Marine Major Gene Duncan spoke of in his 1982 book “Fiction and Fact from Dunk’s Almanac.”

“God made Warrant Officers to give the junior enlisted Marine someone to worship, the senior enlisted Marine someone to envy, the junior officer someone to tolerate, and the senior officer someone to respect.”

Author’s bio: Dr. Nevgloski is the former director of the Marine Corps History Division. Before becoming the Marine Corps’ history chief in 2019, he was the History Division’s Edwin N. McClellan Research Fellow from 2017 to 2019, and a U.S. Marine from 1989 to 2017.