Forgotten Man

By: Sgt Lindley S. Allen, USMCPosted on January 15, 2025

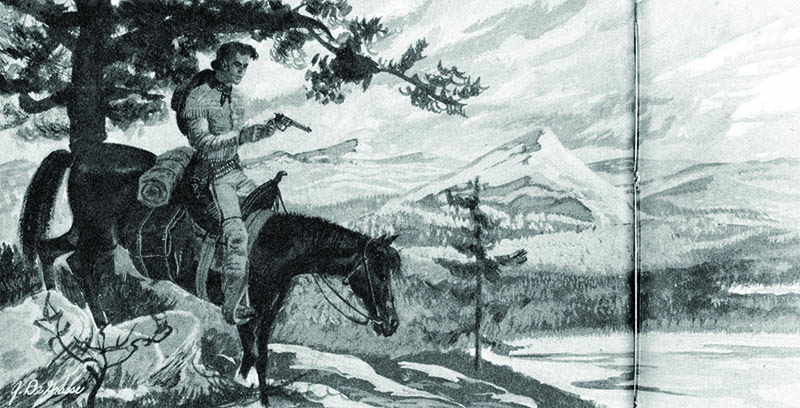

A secret agent can’t win a war all by himself but Archibald Gillespie tried to do it. He was a Marine. The horseman knew he was being followed. An animal perception, sharpened by loneliness and fear, told the Marine Corps lieutenant that the Indians were close on his trail. Unless he could reach Fremont’s camp by nightfall, he knew that his scalp would be passed around a Modoc campfire.

Gillespie’s scalp was not expendable. In 17 years of Marine Corps action, he had risked his neck hundreds of times. This time there was more to lose than his life. He was a confidential agent of President James K. Polk. The information he carried might decide the destiny of California.

Gillespie checked his pistols, estimated the strength left in his winded horse. The sun was low over the pines. He knew that he had two hours at the most. Then something whispered at his left ear, and a slim arrow quivered in a tree beside him. Gillespie spurred his horse and thundered through the forest.

This was Spring 1846. Seven months had passed and 8,000 miles had been covered since Gillespie had sat in the White House listening to the President’s instructions. The precise, clean-shaven Polk was concerned with one thing alone—Manifest Destiny—and moral issues didn’t enter into it. Polk wanted California. At that time California was a province of Mexico and included all of Nevada, half the state of Utah and part of Arizona. Four nations were fighting a cold war for this territorial plum: Great Britain with a good chance, France and Russia with slim chances and the United States in the golden seat. Mexico, the patsy, was taking a siesta.

There was no organized spy system then. Communications were too slow. Polk was depending on two men. One, John C. Fremont of the U.S. Topographical Engineers, operated in the California territory apparently to make maps but was actually a spy and an agent provacateur. The other man, Thomas O. Larkin, was American consul at Monterey.

Gillespie was dealt in on the game simply because he was a fighting adventurer. Polk needed a messenger—someone smart enough and tough enough to travel through several thousand miles of hostile territory and get through in one piece.

Gillespie had fought all his life. His parents in Pennsylvania had christened him Archibald, and he had left a trail of skinned noses and split lips when the boys ribbed him about it. He enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1828 as a private. The pay: $6 a month. In four years, he literally fought his way up to second lieutenant, which position paid the handsome salary of $25 a month. In those days, promotions were almost impossible; they were awarded only for extraordinary heroism. No details are available as to how Gillespie made first lieutenant. He saw action on half a dozen ships and fought in the Indian Wars.

The Marine looked like a fighter. He had enormous hands, the sloping shoulders of a hitter and a tall rangy frame. A superb horseman and excellent shot, he was as equally at home with six gun and saber as he was with his two fists.

“You’ll get through,” said Polk. “If anybody can … .”

When Gillespie left the White House, the conquest of California began. Gillespie, dressed in civvies with the secret documents pinned inside his shirt, boarded a ship for Vera Cruz, Mexico. (Of course, the Panama Canal didn’t exist in those days. Ships bound for the Pacific rounded Cape Horn.)

He traveled overland by horse to Mexico City where he nearly lost his life. The Mexican Army had overthrown the government. The officers had launched a victory celebration on an ocean of tequila. They were betting on war with the Gringos and on Great Britain’s support. (The Mexican ambassador had left Washington on the day of the Texas annexation.) The Mexican officers were laying bets on the cowardice of the Yanquis. To prove it, they rioted through the streets, ripping down the signs of the American merchants, and taking pot shots at any stray American businessmen they could find. Gillespie was disguised as an American businessman.

He left Mexico City faster than he’d arrived—unwounded. As soon as he had reached comparative safety, Gillespie memorized the documents he carried and built a small fire with them. If he died, the secret would go to the grave with him.

He worked his way across Mexico in spite of bandits, soldiery and hostile civilians. At Mazatlan he boarded the USS Cyane, sailed to Honolulu, and from there back to Monterey.

The first part of his mission had taken six months. He delivered the message to Thomas Larkin and shoved off immediately for Yerba Buena (San Francisco) in search of Fremont.

There were all sorts of wild rumors floating around the country. Every tattered settler gave information, about Fremont and the Indians. There was talk that the Mexicans had stirred up the Indians to make war on the Americans. Gillespie rode on.

The Indians picked up his trail in Southern Oregon and stalked him at a leisurely pace, waiting for him to relax his guard, but the wary Gillespie didn’t sleep. The war party could have fallen on him in a body at any time, but they chose to wait.

Gillespie killed his horse in the ride to escape them. Just as the sun disappeared behind the trees on his third day without sleep, Gillespie reached the shore of Big Klamath Lake. A man stepped from behind the trees, palm held outward. Gillespie held his fire. It was Kit Carson, famed Indian fighter and advance scout for Fremont.

Gillespie’s message must have been good because Fremont and the scouts had a celebration that night. In the excitement and hullabaloo, Fremont neglected to post a guard. Even Kit Carson went to sleep with his rifle unloaded.

While the camp slept, the Modocs crept quietly upon them and split the skulls of the two men lying beside Gillespie. It was a good fight, lasting through the night and until noon the next day. Fremont and Gillespie, now second in command, trailed the Indians, killed the Modoc chieftain and most of the raiding party.

For a month, the two secret agents were a sore spot to the Navy which was trying to remain neutral until war was officially declared. Fremont and Gillespie went through California, systematically capturing towns, fighting guerrillas, Indians, anybody who wanted a fight. Some historians say that Gillespie and Fremont were in on the birth of the Bear Flag Republic at Sonoma. (The revolutionists took over Sonoma and established a “New Texas” in California. They needed a flag. A woman sacrificed her underwear, a would-be artist painted a bear on it “that looked like a hog,” and a petticoat waved over a new republic.) The bear flag lasted less than a month, folding when the news of war reached the West Coast.

Gillespie and Fremont were now heartily embraced by Commodore Robert O. Stockton. Gillespie was promoted to captain and Fremont to major. With this promotion, Gillespie became the trouble shooter for the Pacific forces. He had been in hot water for a long time but it reached the boiling point in a few weeks.

Gillespie took part in most of the landing operations at San Francisco, Monterey, San Pedro, Santa Barbara and San Diego. In two months, California had been conquered. All known enemy forces had either laid down their arms or had been dispersed. Mexican General Castro had taken to the hills. Even the Mexican government admitted that California was lost.

Gillespie was left in charge of San Diego with only 48 men. Gen Castro prepared to take the town, but Gillespie organized the settlers into a militia and showed so much strength that Castro took to his heels. This feat of holding a town in hostile territory with a handful of men snowed everybody. A week later Gillespie was in charge of Los Angeles as military commander of all Southern California while Fremont and Stockton shoved off for San Francisco where the Walla Walla Indians were reported to be on the warpath. He was allowed more men for this venture, 59 in all.

Los Angeles was a center of the Spanish population, with a proud citizenry who resented Gillespie. They had buried their silver in the hills and expected the usual treatment accorded a conquered people.

Some historians accuse Gillespie of being a petty tyrant. He established curfews and ordinances that irritated the people. His men, untrained roughnecks, mustered into the Navy for a short term, increased resentment. They promptly tried to drink up all the wine and aguardiente in the area—and there was plenty of it.

But the real cause of the revolt against Gillespie was the $20,000 that he had drawn from the U.S. Congress for military expenditures. As soon as the natives learned of this hunk of dough, they became fiery patriots. A group of adventurers led by Cervula Varela plotted to seize the garrison and the money.

Then Gillespie cracked down. He promptly arrested everyone who looked suspicious. He made his men snap-to. But when he looked at the proud American flag flying over his compound, he grew uneasy. The water supply was low. Provisions were depleted. Ammunition was short. Before Gillespie could alleviate the situation, the first attack came.

Gillespie’s men drove them back easily, and that merely increased the bitterness against him. The natives dreamed about the $20,000. Jose Maria Flores, the big shot in that area since Castro had retired from the neighborhood, heard about it and took charge. A force of 400 gathered around Flores; they unearthed the cannon which Castro had hidden in the hills and laid systematic siege to Gillespie’s command.

There was no hope for Gillespie but he wouldn’t give up. He had a few abandoned guns which had been spiked. He drilled out the spikes, mounted them on ox carts, and improvised ammunition for them. He had never run away from a fight, and he’d be damned if he’d run away from this one.

Flores’ force grew by the hour as more patriotic Mexicans heard of the money in Gillespie’s hands. Flores met Gillespie under a flag of truce and demanded unconditional surrender on the 25th of August. The terms of surrender were no good. Flores wanted Gillespie to lay down his arms and walk out where he could easily be shot down. Gillespie told him what he could do with his offer and warned Flores that he’d fight to the death. The Mexicans hesitated. Gillespie sent a messenger to Stockton, but there was no hope that reinforcements would arrive in time to save him.

Meanwhile Captain Watson, with 25 volunteers, rode down from the north to break the siege. He was immediately captured. Gillespie’s officers and men persuaded him to make terms. Finally with the greatest bitterness he would ever know, Gillespie exchanged prisoners, agreed to a surrender with “full honors of war” and hauled down the American flag.

That flag never left his possession in the months that followed.

It was his responsibility. He felt that he had brought dishonor to himself and to his country. He marched to San Pedro with his men, and when he learned that the Mexicans were planning to violate their agreement, he set his men aboard the Vandalia at San Pedro where they would be safe.

There was an immediate attempt to recapture Los Angeles after Captain Mervine of the Savannah arrived at San Pedro. Gillespie and his men took part in it, but the Mexicans with artillery and horses hammered away at the foot soldiers. When the Americans retired, Gillespie offered to stay in San Pedro, but Capt Mervine refused. Enough lives had been lost.

Meanwhile San Diego had been besieged. Gillespie was transferred there and was successful in breaking the siege. Stockton was making plans for the recapture of Los Angeles but at this point, word was received that Colonel Stephen W. Kearney and his so-called “Army of the West” had arrived at Warner’s Pass about 50 miles east of San Diego. Someone had to reach him in time to prevent an ambush.

Gillespie, of course, drew the assignment. With 26 of his ragged volunteers, he met Kearney at Warner’s Hot Springs on Dec. 5. The “Army,” consisting of less than 100 dragoons and eight officers and scouts, had marched overland from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. It included the rugged Kit Carson, who got around about as much as Gillespie.

An ambush had been laid for Kearney, forming at San Pasqual, later taking positions in a narrow valley behind a stream. The Mexicans were superbly mounted, armed with muskets, sabers and vicious willow lances. Their leader Dolores Higuera, “El Guero,” drew Kearney’s dragoons into a disastrous charge by a clever fake retreat. Kearney’s horses were in no shape for a sustained gallop, and after they had strung out over several hundred yards, the Mexicans wheeled and swept back toward them. The engagement was short and bloody. In five minutes, 18 of Kearney’s men were killed, and many more were wounded.

Gillespie arrived as the Mexicans attacked. He drew his saber, spurred his horse, and drove into the thick of it. “Hold men,” he bellowed. “For God’s sake rally. Show a front. Face them.” El Guero, attracted by the loud cries, attacked Gillespie from the side and drove his bloodstained willow lance through the Marine’s cheek.

Gillespie hit the ground, fully conscious, his face a mass of blood. He lay still, feigning death, while El Guero took his horse, saddle and even the beautiful serape lying beside the Marine. The Army of the West, now reduced to one third of its original strength was probably the most tattered, ill-fed detachment that the United States has ever mustered under her colors.

Gillespie bore a charmed life. He took part later in the overland march to Los Angeles. He led repeated charges in the battle of San Gabriel and was wounded again. He tied rags around his wounded legs and rode on to fight heroically in the Battle of La Mesa.

In January 1848, the Marine limped to the center of the plaza in Los Angeles. He carried a flag, now spotted with his own blood, but the same Stars and Stripes he had been forced to haul down four months before. He attached it to the halyards, gave a command, and watched Old Glory ride to the top of the mast.

That moment was his reward.

Three weeks later James W. Marshall discovered gold at Sutter’s Mill. In the stampede that followed, Gillespie was forgotten. He earned no fame; only two history books mention his name. He stayed in the Corps until 1854, earned the title of brevet major and remained in the West until his death in San Francisco in 1871.