Giants of the Corps: Archibald Henderson

By: Karl Schuon and Tom BartlettPosted on December 15, 2024

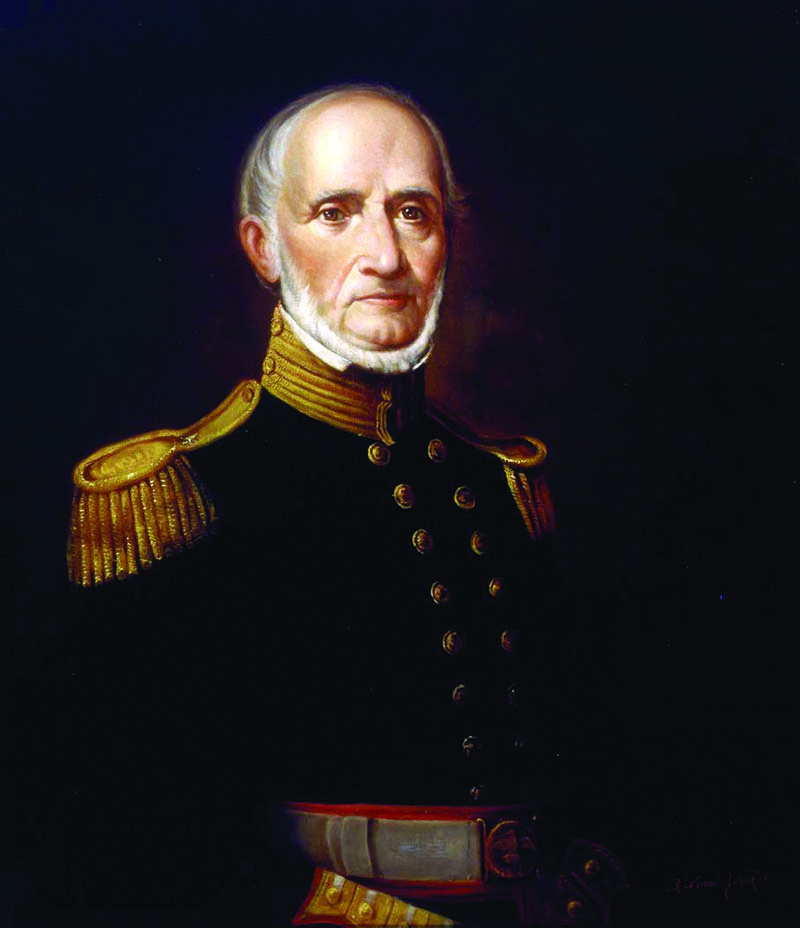

Executive Editor’s note: Fifty years ago, Leatherneck began looking ahead to the Marine Corps’ 200th Birthday, and started a series in the magazine called Giants of the Corps. As we are poised to celebrate another milestone birthday, we thought it fitting to revisit this article about the 5th Commandant of the Marine Corps, Brevet Brigadier General Archibald Henderson. In this month’s magazine, we are focusing on the years 1820-1840. Henderson, known as the “Grand Old Man of the Marine Corps,” was appointed Commandant in 1820 and served in that role for 38 years, shaping the legacy and traditions of the Marine Corps for years to come.

As Marines prepare to step into the third century of service to their country, it is well that we pause, reflecting on the actions, words and lives of some of the great Americans who gave so much to our Corps.

When President James Monroe appointed Brevet Major Archibald Henderson a lieutenant colonel and Commandant of the Marine Corps on Jan. 2, 1821, with date of commission of Oct. 17, 1820, he christened what has come to be known as “The Henderson Era.”

It is difficult to imagine Archibald Henderson as anything but the Commandant. It was as though he were destined for the awesome responsibilities of the office. His tenure of office was to last for 38 years of growth, tradition, respect and new glory.

There are many legends concerning the service, determination and “spirit” of General Henderson. “Spirit” defined in this case as “mind and temperament” and as an “apparition.”

Born in January 1783, he was appointed a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps in June 1806. As a captain during the War of 1812, he served aboard the frigate Constitution and participated in the engagements against the Java, Cyane and Levant. With less than 15 years of service as a Marine, he was appointed Commandant!

He took over at a poor time. He had inherited a Corps weakened in morale. A private received between 6 and 10 dollars a month, and chances are, he didn’t draw even that amount. It was believed at that time that desertion could be discouraged by withholding a small percentage of a man’s pay until the individual’s enlistment had expired.

NCO’s pay started at $8, and climbed to $17, the pay of a sergeant major. Second lieutenants received $25. The Commandant was paid $75 a month.

Henderson lost no time in building what he envisioned to be “the finest military organization in the world.” He personally led an extensive inspection tour of men, gear and stations. He found his men serving with the attitude that nobody cared.

He reasoned that his Corps would be no better than its officers, and therefore stationed all newly appointed officers at his own headquarters, Marine Barracks, Washington. There they would receive his personal supervision before being assigned to sea duty.

Morale began to climb as the men realized that the Commandant himself was personally supervising all matters pertaining to their pay and allowances.

How was his morale about this time? A 39-year-old bachelor, he married 19-year-old Anne Maria Casenove in October 1822. The couple moved directly into the Home of the Commandants.

While preparing for a reception the young wife asked: “What are those tables for?”

“Why, for playing cards,” a servant told her. “Gentlemen always play cards after supper.”

“Well,” said the new mistress of the Home of the Commandant, “you may just put them away. No cards will ever be played in my house!”

Anne Maria Henderson’s first directive in the house on “G” Street was upheld for the 36 years she lived there. Six children were born to the Hendersons while they occupied the house. Archibald Henderson’s first decade as Commandant provided him time to achieve the efficiency in both the ranks and administration that he sought.

In 1824, during the Boston Fire, his Marines were called out for rescue work and additional police duties to prevent looting following the holocaust.

Not long after, one officer and 30 Marines quelled a riot of 238 prisoners in the Massachusetts State Prison when the situation became too desperate for local authorities to handle.

These incidents and others like them, although unfortunate, were exactly what Henderson needed to bring his Corps into sharp focus with the American public, for the Commandant had long recognized the political advantages which would follow—if the Marines gained outstanding popularity with the public.

His “community relations” program was to pay off on Feb. 20, 1829, when the Center Building was destroyed by fire. The Commandant reported in a letter to the Secretary of the Navy, Samuel T. Southard:

“The fire is supposed to have been caused by burning the chimneys in the forenoon, and to have communicated itself to the interior of the third story by some imperfection in them. The two wings were saved by the preserving and arduous exertions of the different fire companies, and the citizens generally. …”

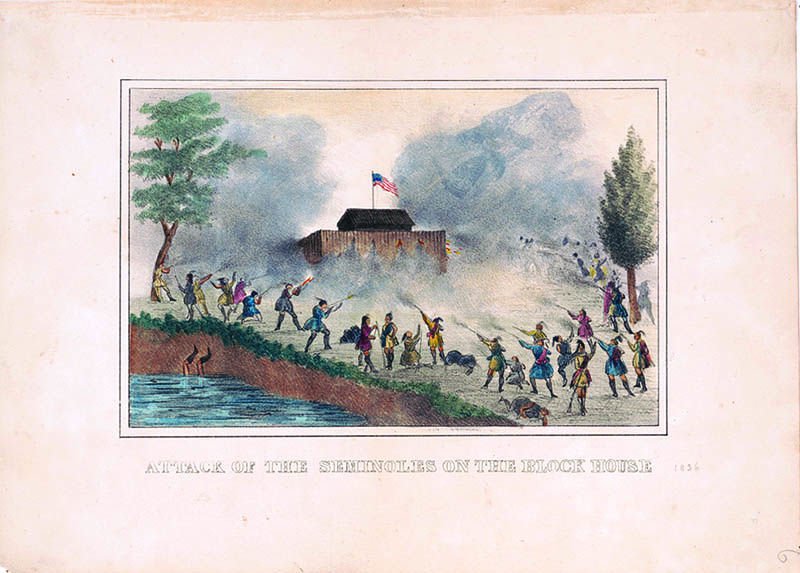

Indians in Florida massacred an Army column in December 1835. Florida slaves had, for a long while, been making their escapes permanent by joining the Seminole Indians, often intermarrying.

Southern landowners complained to the government, and finally, a treaty was made with the Seminoles. Under the terms, the Indians would be taken under federal protection and assigned to reservations. The Indians, however, rebelled when they discovered that the reservations were situated in the territory that is now the state of Arizona.

“Snow covers the ground,” they reported, “and frost chills the bodies of men.” The bronzed Seminoles, who had for centuries lived in the balmy, breezes of Florida, were not to freeze in Arizona.

During early 1836, the Army had borne the combat load, playing a frustrating game of chase with the elusive Indians in the Everglades. Marines of the frigate Constellation, the sloop St. Louis and the sloop Vandalia had participated in the fighting.

Early in spring, Commandant Henderson wrote a letter to President Andrew Jackson, volunteering a regiment of Marines to support the Army. On May 21, the President accepted, ordering all available Marines to report to the Army.

Henderson, then 53, chose to lead his men in the swamps of the Everglades in pursuit of the Seminoles. Gathering together nearly all his officers, he reduced shore station detachments to a mere sergeant’s guard, and leaving behind only those unfit for duty, he managed to muster almost half the entire strength of his Corps.

On June 1, 1836, he placed LtCol R. D. Wainwright in charge of the Marine Barracks, “8th and I.”

“I leave you a most valuable soldier in the sergeant major,” Henderson wrote Wainwright, “whose health entirely incapacitates him from going on the expedition. He is anxious to go, but as a matter of duty, I have ordered him to remain, as I cannot take any other than able-bodied men on such arduous Service.”

In spite of the letter to Wainwright placing him in command, the legend persists that the Commandant closed up Headquarters Marine Corps, locked his door and tacked up a sign which read: “Have gone to Florida to fight the Indians. Will be back when the war is over. A. Henderson, Col., Commandant.”

While Henderson and his force of 38 officers and 424 enlisted were in Florida, his losses were heavy. He returned to Washington in the summer of 1837. He had lost 61 Marines in combat, but in addition, he had “lost” two companies totaling 189 men and officers who had remained behind. These men were stationed along the Florida coast, around the Keys, and with the Mosquito Fleet.

With his entire Corps numbering less than 1,000 men, the Commandant was having difficulty fulfilling his commitments without the loss of two companies serving where he considered their presence unnecessary.

He spent the next five years battling to get them back, stating that he no longer had “men sufficient even for an ordinary morning parade, or for a company drill.” Henderson was also fighting a battle with the Treasury Department.

While he was absent on the Seminole Campaign, the Commandant’s Quartermaster “requisitioned” a Nott stove for use in the Henderson home.

The Commandant, upon his return, was informed that the stove was apparently a luxury item, and therefore, not something for which the U.S. government would pay. He received a bill in May. Another bill arrived in June. The letter he received dated July 14, 1838, read in part:

“For Nott Stove, $98.80. … To the liquidation of which I have to call your attention, otherwise the Pay Master will be instructed to Check the amount from your pay.” Could the Commandant’s pay be “docked” for a “luxury” item …. a stove?

Evidently approval by the Secretary of the Navy for payment of the stove came later, since no further correspondence ensued. … Unless, of course, Henderson paid for the stove himself, which is doubtful.

“The Henderson Era” brought continued changes. On July 4, 1840, Commandant Henderson issued orders that the Marine uniform would be changed from green to blue with scarlet trim. In 1842, he requisitioned artillery for training purposes at Headquarters, New York, Boston, Norfolk, Philadelphia, Portsmouth and Pensacola.

The Commandant noted that various Navy Yards had begun to develop libraries, and in September 1843, he addressed the Secretary of the Navy, requesting books.

There are 54 titles on the list he submitted, but not one of them appears to have been intended for off-duty, pleasure reading. “Maury’s Navigation” and Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” were included, as well as “An Encyclopedia (Cheap Edition).”

During the next three years, unrest began to grow in a vast piece of real estate, called by the Mexicans, “Tejas.” Here, in this sparsely settled land, Americans had built homes and formed the Republic of Texas. The “republic” had been admitted to the Union, but a controversy over the designation of the Rio Grande as a boundary rekindled old Mexican contentions for ownership.

Battles had already begun to rage when, on May 12, 1846, the United States formally declared war on Mexico.

By this time, Archibald Henderson was 63 years of age. He decided to remain at home, directing the destinies of the Corps from the Marine Barracks. A Marine regiment under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Watson was assigned to support the Army under the command of Lieutenant General Winfield Scott.

The newly formed regiment of Fort Hamilton, N.Y., was joined by 63 Marines of the Washington Barracks, and they sailed for Vera Cruz. The Marines were first a brigade with the 2nd Pennsylvania Volunteers, in reserve. When Scott attacked the approaches to the Citadel of Chapultepec, he found Mexican resistance furious and formidable. He called the Marines.

Two assault parties of more than 500 Marines, along with Army volunteers, were formed to spearhead the attack. A pioneer force of 70 Marines was equipped with scaling ladders, crowbars and pickaxes. At dawn, following a heavy shelling, the Marines ramrodded through. The general attack was a bloody hand-to-hand battle of bayonets, swords and rifle butts.

In his report to Henderson, General Scott said of the Marines, “I placed them where the hardest work was to be accomplished, and I never once found my confidence in them misplaced.”

The decade following the close of the Mexican War was an interlude of uneasy peace for Henderson’s Corps. On Oct. 31, 1850, its strength was 70 officers and 1,210 enlisted. While about half the Corps was engaged in training and shore duty, Marines serving as ship’s detachments were going ashore to protect American lives and property in Latin America.

In 1833, Marines played an important role in peaceful missions to persuade Japan to open her trade to the world.

In 1856, U.S. ships were in Chinese waters, landing Marines to protect American property. At Canton, 181 Marines and Sailors went ashore, where they manned fortifications around the American compound. On their return to their ships, a Chinese fort opened fire on the men.

In answer to the unprovoked act, the American ships began a series of attacks on Chinese forts until Nov. 16, 1856, when an emissary of the Imperial Commissioner of Canton came aboard the American flagship to apologize. That ended the hostilities.

A few blocks from his own doorstep, Commandant Henderson could hear the rumblings of trouble in 1857, when election issues were being bitterly contested. In a desperate attempt to control the election, the “Know Nothing” Party had brought in gangs of hired thugs, known as the “Plug Uglies,” from Baltimore to threaten physical harm to the voters and eventually seize the polling places throughout the Capital to halt the elections.

Civil authorities, unable to quell the rioting, asked the President for help. He went to Henderson, who was directed to send the entire force from the Marine Barracks to prevent bloodshed at the polls.

“The force,” the Commandant wrote in a report, “was prepared with all possible dispatch and the cartridge boxes filled with ball cartridges. … It was formed in line, and I addressed a few words to the troops.”

Henderson, now 74, did not attempt to lead them, but he did stroll in civilian clothes, toward City Hall. He arrived as the Marines were deploying in front of the building.

“I repaired to the office of the Mayor,” Henderson’s report stated, “and offered my services to him, as a citizen to aid him in the performance of his duty. He accepted my offer very cordially.”

Henderson followed the mayor into the streets, where they heard rumors that a cannon had been set up near the market. Determining that the rumors were true, Henderson instructed one of his companies to capture it.

Henderson himself strolled through the crowd and to the rear of the gun. Advancing toward the muzzle (placing himself between the gun and advancing Marines) the Commandant instructed: “Now is the time to order the capture!”

He then directed Maj Zeilin, “the soldiers, quick, quick,” and with a rapid charge, the rioters were driven from the gun.

After the capture of the cannon, the Plug Uglies continued to fire pistols. Marines returned the fire. Believing that the skirmish was over, Henderson ordered the Marines to hold their fire.

“A man came rapidly through one of the openings in the Market House,” Henderson wrote, “discharging a pistol in the direction of a sergeant and myself, then turned to save himself by flight … I jumped forward and seized him by the collar and made him my prisoner. …”

In 1858, the strength of the Corps was at a new high of 63 officers and 1,789 enlisted and its reputation as a dependable force in readiness had reached an unprecedented stature.

It was on this excellent plane of efficiency that Archibald Henderson left his beloved Corps, when on Jan. 6, 1859, he returned from a walk to Alexandria, laid down on a sofa before supper and died quietly in his sleep.

Funeral services for Brevet Brigadier General Henderson were conducted at the Marine Barracks. President James Buchanan, his Cabinet and many high-ranking officers of other services attended. The President is said to have walked behind the hearse from the Barracks to the old Congressional Cemetery where the Commandant was interred. His wife followed him in death 13 days later.

One son, Charles A. Henderson, a second lieutenant in the Corps, had fought in the Mexican War and served his father as an aide. With the approach of the Civil War, he resigned his commission to join the Confederate States Marine Corps, remaining loyal to Virginia, his father’s native state.

There is a legend that he willed the house on “G” Street to his wife. The legend is easily disproved.

But there are other Henderson legends that are more difficult to explain. The wife of a much later Commandant awoke during her first night in the house and found an elderly man with a white fringed beard and wearing a historic Marine dress uniform, sitting quietly in a chair before the smoldering embers of her bedroom fireplace. Aware that his presence had been observed, the man arose, bowed politely and vanished.

The following morning, she described her visitor of the previous night. When the Commandant returned home that evening, he brought with him a portrait of General Henderson.

“That,” said his wife, looking intently at the painting, “is the gray-bearded gentleman who was in my room last night!”

Many years later, Feb. 13, 1945, General Thomas Holcomb was entertaining dinner guests. He mentioned that, among other affairs that day, he had signed an order establishing the Women’s Reserve.

“Old Archibald,” he said, “would turn over in his grave if he ever found out that females could become commissioned officers in his beloved Marine Corps!” Scarcely had the words been said when Henderson’s portrait crashed to the floor.

If, indeed, these legends of Henderson’s metaphysical visitations are true, it may also be true that he reserves his manifestations for the old house, knowing that his spirit with which the young Marine Corps was so thoroughly imbued, still remains strong in the Marine of today, who needs no reminder from the past to help him uphold the glory of his Corps.