Alfred A. Cunningham: Father of Marine Corps Aviation

By: Dr. Laurence M. Burke IIPosted on April 15, 2025

Alfred Austell Cunningham is rightly celebrated as the “Father of Marine Corps Aviation.”

His arrival at the Navy’s aviation training camp is the birth date of Marine aviation, and in fact, his own lobbying for aviation in the Marine Corps led to his assignment in aviation training. He is well known for his nearly 10 years of de facto leadership in the field of aviation, but what is less well known is the lasting impact that he has had on the fundamental nature of Marine Corps aviation, specifically, his maxim that the only reason for Marine aviation is to support the Marine on the ground—an idea that remains part of the organizational identity today. Though Cunningham did not express this idea explicitly until 1920, there is evidence that it was a driving idea, albeit perhaps unconsciously, of his vision for Marine aviation from the very beginning.

Not much is known about Alfred Cunningham before he became a Marine in 1909. He was born in Atlanta, Ga., in 1882, the sixth child (and fourth son) of John Daniel and Cornelia Cunningham. The one incident from his life before the Marine Corps, and the one most often mentioned, is his ascension in a balloon in 1903, which reportedly engendered his interest in flight.

Nothing in the documents found indicates why Cunningham applied for a Marine commission in 1908, but his application was successful, and he took his oath of office on Jan. 25, 1909. After attending the Marine Officer’s School at Port Royal, S.C., he was assigned to various ships’ Marine detachments. In July 1911, Cunningham was “stashed” on the receiving ship in Philadelphia, awaiting his next assignment to the newly established Advanced Base Force, where he reported on Nov. 11, 1911.

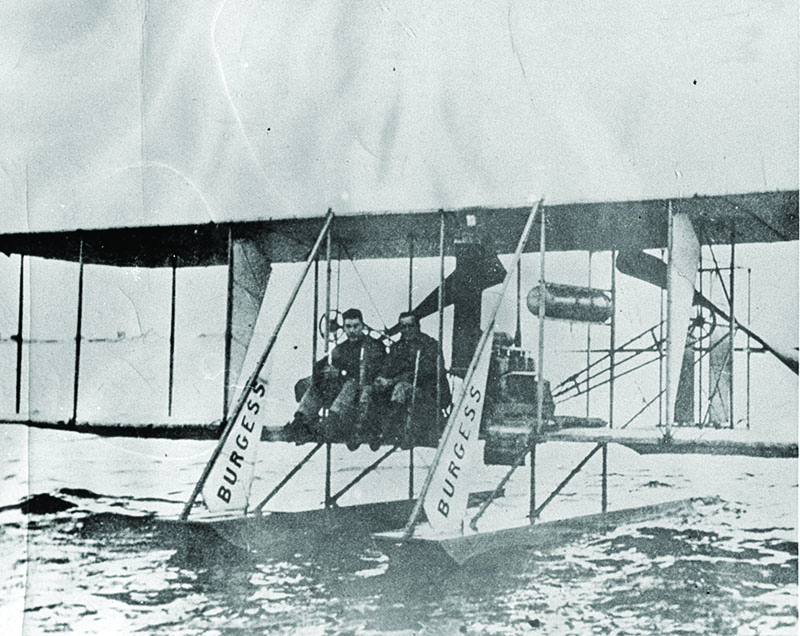

In Philadelphia, Cunningham was finally able to pursue his aviation interests. Soon after checking in aboard the receiving ship, he quickly found an airplane he could borrow to try to teach himself to fly. He nicknamed it “Noisy Nan.” He secured permission from the Navy Yard CO to use a field on the base, and he made his first attempts to pilot the plane less than a month after reporting to Philadelphia, though Nan was too underpowered to fly.

Cunningham also connected with the Aero Club of Pennsylvania, a group that included prominent Philadelphia businessmen interested in promoting aviation. According to at least one history, he persuaded members of the club to lobby Congress for a Marine flying field at the Navy Yard. Reportedly, Major General Commandant William Biddle, found out Cunningham was behind the campaign and agreed to send him for flight training if he got the club to stop badgering Congress.

The ABF had developed from lessons learned by the Navy in the Pacific during the Spanish-American War. Its purpose was to protect an advanced base (a protected anchorage) where the Navy could repair and refuel after crossing the Pacific before going into battle. The Marines, however, had only been given responsibility for defending such a base against landward attack in 1910. The newly established ABF school was as much about deciding what the ABF should be as it was about teaching that doctrine to Marines. Thus, it was not untoward for Cunningham to make a recommendation about the force.

On Feb. 12, 1912, Cunningham wrote a letter to the ABF School’s commanding officer recommending the purchase of airplanes for the ABF, arguing that “the necessity for an aeroplane is constantly and emphatically evident” and that airplanes for reconnaissance were “necessary to the proper efficiency of the Marine Corps.” The letter worked its way up to Biddle, who agreed that aircraft would be useful to the ABF.

Though Cunningham did not explicitly describe aviation as he would in 1920—with its purpose being only to help the Marine on the ground—this supporting relationship was inherent in the proposal. He did not say that the airplane could or would act independently. He was describing it, in modern terms, as a force multiplier: something that would make the ground Marines more effective. Admittedly, the technology of the airplane at this time meant that it was incapable of independent action. On the other hand, that did not stop some flight enthusiasts from anticipating that that would soon change. However, Cunningham never advocated for independent aerial missions.

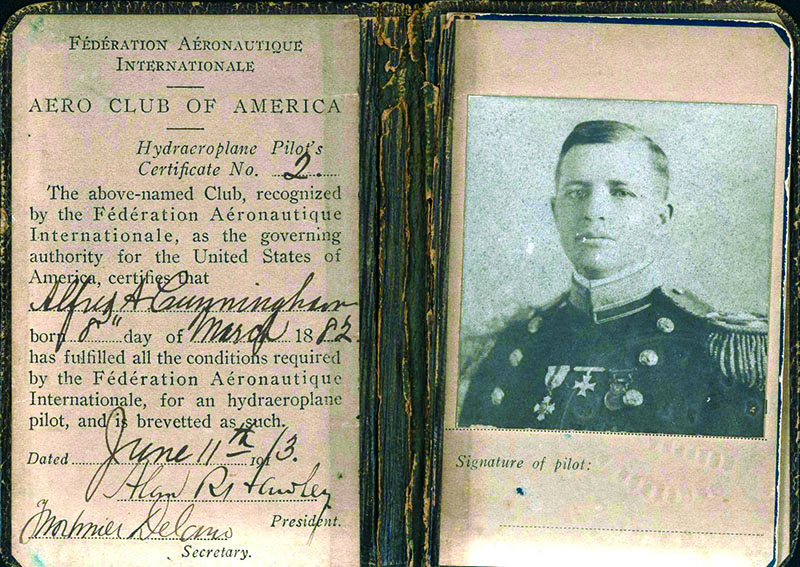

Biddle consulted with the Navy Department, which agreed that airplanes would be useful to the Marine Corps and suggested that Marine officers be sent to the Navy’s aviation camp for training and experience. Cunningham got his orders, reporting to Annapolis, Md., on May 22, 1912. The second Marine aviator, Bernard Smith, also got orders to aviation at this time but did not report until September.

While Cunningham had envisioned a particular mission for Marine aviation, neither he nor Smith had much opportunity to practice a uniquely “Marine” form of flight. All of the naval aviators needed to gain experience in the air and transition from simply learning to fly safely toward learning to navigate and become useful in the air. At the same time, the small naval aviation camp needed to do its own experiments with aircraft. Flying time with the limited number of aircraft was a scarce commodity.

In August 1913, Cunningham had to leave flying behind. His fiancée, Josephine, refused to marry Alfred if he was actively flying. Though he was out of the pilot’s seat, he remained connected to Marine aviation, serving as the Corps’ representative on the Navy’s Board on Aeronautics. The “Chambers Board” as it was known (after its chair, Navy Captain Washington I. Chambers), was intended to create a comprehensive plan for naval aviation. Its final report on Nov. 25, 1913, among other recommendations, proposed purchasing six aircraft for the ABF along with all necessary equipment and even suggested designating auxiliary vessels to carry all of it for expeditionary service. Such considerations likely reflected Cunningham’s presence on the board. On the other hand, he missed out on the one pre-war opportunity for Marine Corps aviation to operate independently: as part of the ABF maneuvers at Culebra, Puerto Rico, in early 1914.

By 1915, he was apparently able to change Josephine’s mind, as he returned to aviation, with the stipulation that he would have to go through the training curriculum as it then existed. He finished the Navy’s new schooling in September, and in the spring of 1916, he requested to be sent to the Army’s flight school in San Diego. Landplane and seaplane flying were considered very different skills at the time, with landplanes exclusive to the Army. Cunningham, recognizing that an effective aviation section for the ABF would need both types of planes, wanted to be trained in both. He received the requested orders and reported to San Diego at the end of June.

While he was traveling to San Diego, the Navy officer at the “aviation desk” in Washington proposed that the Navy establish the aeronautic section of the First ABF in Philadelphia as soon as possible. He recommended that the unit consist of two airplanes, two seaplanes, two observation balloons, and the equipment and personnel to operate and maintain them in the field. The suggested table of organization and equipment closely matched the ideas of Bernard Smith following the 1914 Culebra maneuvers. Commandant George Barnett, who had replaced Biddle in 1914, agreed with the proposal, issuing orders on Aug. 24 to establish the aeronautic unit in Philadelphia.

While Cunningham had missed out on the Culebra exercises, he returned to aviation intent on establishing a distinct Marine aviation identity. He responded to the Aug. 24 order as though he were going to be in charge. He wrote to Barnett on Aug. 29 giving preliminary recommendations for the aeronautical unit, promising to send an itemized list of equipment, machinery, and tools needed at the new airfield along with his own wooden hangar design. He likely finished Army flight training before October 1916, but other duties kept him on the West Coast for several more months. At the end of January, Barnett ordered Cunningham to Philadelphia, on temporary duty, to inspect the proposed flying field and make recommendations for the physical organization of what was soon to be known as the Marine Aeronautic Company. While Cunningham had put considerable work into planning and organizing the aeronautic company, he was not formally named its CO until Feb. 26. However, he was still wrapping up work for another Navy board (examining sites for new bases and airfields) and did not officially arrive in Philadelphia until March 3.

As soon as the United States declared war against Germany on April 6, 1917, Barnett began advocating for the Marines to have a combat role alongside the Army. This would eventually take the form of the 4th Marine Brigade of the 2d Division, American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). Headquarters Marine Corps proceeded on the assumption that the Corps would provide its own aviation assets for the brigade as called for by the Army’s tables of organization and equipment. On July 27, Barnett proposed that the Marine Corps organize a squadron of landplanes “for service with the Marines in France.” Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels approved this plan on Aug. 20 and directed Barnett to contact the Army’s Signal Corps, in charge of Army aviation, to discuss equipping and training the squadron.

On Sept. 17, Barnett wrote to the Army’s Chief Signal Officer proposing that the Army train one balloon company and one landplane aviation squadron of Marines for service in France. On Oct. 10, Cunningham reported to Barnett that the Army would train the Marine Aviation Squadron in both basic and advanced flight training in landplanes. He wrote that once the training was complete, “the Squadron [would] then be ready for service in France and the Army [would] completely equip it with the same technical equipment furnished their squadrons.” At the same time, eight Marine officers and six enlisted Marines would be sent through the Army’s Balloon School to learn balloon ground crew duties. The Marines would then have flyers and balloonists ready to support the Marines on the front lines in France.

Though the Army had agreed to train the Marine flyers, the nature of that service had not been specified. Sometime in October, the Army told Cunningham that it would not let Marine aviation provide air support for the Marine brigade. This was not simply Army aviation wanting to keep all the glory for itself: The Army at this time was recycling most of its own newly fledged aviators as well as Marine aviators back into the training pipeline as instructors. Even in France, the Army never had enough squadrons to permanently assign a squadron to divisions or even corps, much less brigades!

Not happy with a non-combat role, Cunningham arranged orders for a trip to Europe. Ostensibly, his purpose was to investigate French and British training methods. He later admitted, though, that he had made the trip hoping he could get the AEF staff to give Marine aviation a combat role. He arrived in France on Nov. 18, 1917. He packed a lot into his inspection tour, but he was no more successful in talking the AEF into giving Marine aviation a combat role than he had been with Army officials in Washington. All was not lost, however, as he did come back from Europe with an idea for how Marine aviation could contribute in a combat role.

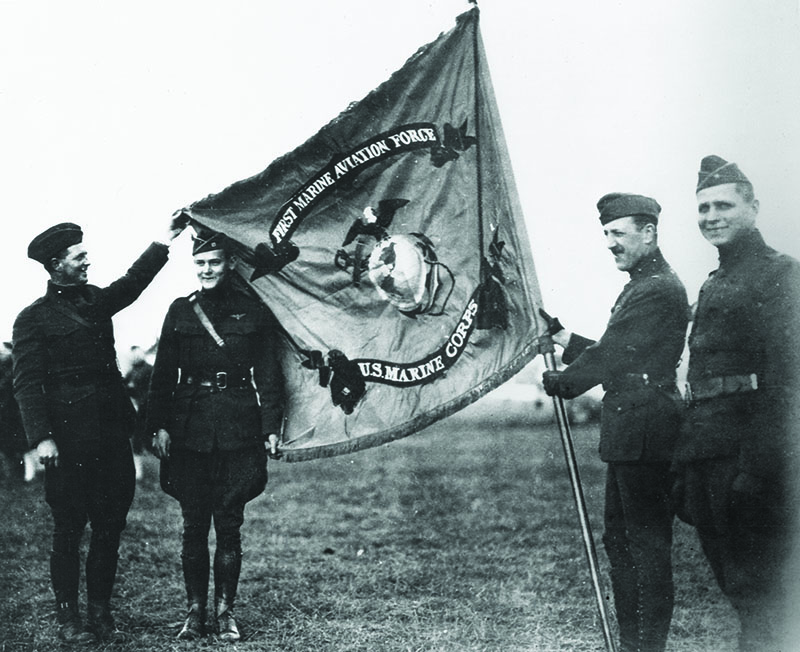

During his tour, he had learned of British attempts to bomb German submarines as they transited in and out of captured Belgian ports. The subs were particularly vulnerable here as extensive shallows forced them to remain on the surface for miles and limited their ability to evade attacks. German countermeasures included heavy coastal artillery guns to keep ships out of the area and land-based fighter squadrons to prevent aerial attacks. Cunningham believed that a few squadrons of land-based Marine Corps fighters could provide the necessary escort for Navy seaplanes to bomb the submarines. He returned to the United States in January 1918, presented his proposal to the Navy’s General Board on Feb. 5, and on March 11 received orders to proceed to Miami to begin assembling four Marine fighter squadrons as the First Marine Aviation Force (FMAF).

Cunningham’s idea did not get Marine aviation to France to support the Marine brigade, but it did get his aviators into combat. As it happened, the nature of what became the Northern Bombing Group (NBG), and the FMAF’s role in it, changed significantly even before the first FMAF personnel reached France. On April 30, the Navy authorized what would eventually be known as the NBG—the name changed several times as the plan was developed—for a round-the-clock bombing campaign against the U-boat bases in occupied Belgium. The four Marine squadrons Cunningham was training up would become the Day Bombing Wing of the NBG.

Cunningham and three of the squadrons arrived in France on July 30. But because of supply problems, they did not yet have any airplanes. Cunningham arranged with the British Royal Air Force (RAF) to have small numbers of his aircrew rotate through the nearby RAF No. 217 and No. 218 Squadrons, which flew very similar aircraft to what the Marines were expecting. The arrangement gave the Marines an introduction to combat alongside veteran aviators and the RAF a solution to their personnel shortages.

Both RAF squadrons were dedicated entirely to what today would be called air support and interdiction missions in support of the Allied armies in Flanders. Even once the Marine Day Wing began getting its own aircraft, it continued to work closely with the two RAF squadrons. In doing so, the Marine squadrons had drifted considerably from both Cunningham’s original plan and the Navy’s intent for them as part of the NBG. However, they were getting experience in the kind of warfare that Cunningham originally sought: they were supporting troops on the ground.

When the armistice appeared imminent, Cunningham began angling to have the Marine aviators sent home as soon as possible. The Marine Day Wing arrived back in Miami in January and February of 1919, where the unit was disbanded and most of the personnel demobilized. The same happened to the First Marine Aviation Company (which had been flying anti-submarine patrols in the Azores) in March.

Back in the United States, Cunningham resumed his efforts to establish an independent Marine aviation. Barnett formally named him head of the Marine Section of Naval Aviation, and Cunningham was quick off the mark with a “Proposed Program for Marine Section, Naval Aviation.” This three-page document, dated Jan. 13, 1919, proposed a “definite program and mission for the Marine Aviation Section.” Cunningham reiterated that the Marine aviators with advanced base and expeditionary operations would need to be trained in both land and seaplanes. Despite his antagonism toward the Navy in some of his letters both at the time and later on, he insisted in this document that the Marine Section should continue to be closely associated with the Navy by continuing to train and operate alongside Navy pilots. Perhaps he recognized the political necessity of remaining on good terms with the Navy, which, after all, was—and remains—responsible for providing airplanes and necessary supplies and equipment to the Marine aviation program.

Cunningham urgently wanted to get aviation into the field too. In Miami, those personnel who had not been demobilized were redistributed among the five extant Marine squadrons (four from the Day Wing and one, Squadron E, from the Azores). The 1st Division, Squadron D, left Miami to work with the Second Provisional Brigade in the Dominican Republic in February 1919. Squadron E left the following month to work with the 1st Provisional Brigade in Haiti. Other squadrons established new Marine airfields at Quantico and Parris Island.

During this reshuffling, the Navy General Board’s hearings on naval aviation policy in early 1919 also considered a Marine aviation policy. Cunningham appeared before the Board on April 7 to speak for Marine aviation, telling the Board, “I believe there is an important logical and well-defined mission for the Marine section and that is to furnish the air force required for operating with the advanced base and expeditionary forces.” When the Board asked whether Marines really needed their own airfields—whether they could not continue using existing Navy fields—Cunningham explained his belief that Marine airfields should be established near the ground forces they were to work with so that air and ground units could practice together. The General Board’s final report recommended that the Navy Department acquire kite balloons, landplanes, and seaplanes for use with Marine Corps advanced base units. The Board also suggested that each ABF unit should have an aerodrome nearby to improve air-ground cooperation. This relationship was something Cunningham had wanted from the very beginning, and this was his first chance since 1912 to clearly reiterate it.

Cunningham had another chance to influence official doctrine around that time. In a letter to the Navy Bureaus and the Commandant describing the plans for Naval Aviation in the 1920 fiscal year, Chief of Naval Operations William Benson stated (or at least signed off on the statement) that, “The most important work ahead of [M]arine aviators is to prove to the ground troops that they can be of real service to them in carrying out their war duties. This can only be done by actually operating with them.” Following this was a long list of specific duties for coordination with infantry and artillery, which Marine aviators would be expected to train for. While the letter appeared over Benson’s signature, Cunningham more than likely contributed the original draft of this portion of the plan.

Cunningham’s article in the September 1920 Marine Corps Gazette, “Value of Aviation to the Marine Corps,” likely drafted about the same time as the input to Benson’s report, is more open about some Marines having a poor opinion of aviation. Early in the article, Cunningham cites the need for Marine aviation to “overcome a combination of doubt as to usefulness, lack of sympathy, and a feeling on the part of some line officers that aviators and aviation enlisted men are not real Marines.” A bit later, Cunningham states, “Having in mind their experience with aviation activities in France, a great many Marine officers have expressed themselves as being unfriendly to aviation and doubting its full value.”

He explained the issues that prevented the FMAF from serving with the 4th but went on to say that, with the conclusion of postwar reorganization in the States, “we are looking forward with enthusiasm to our real work of cooperating helpfully with the remainder of the Corps.” Cunningham tried to reassure the doubters, stating that “the only excuse for aviation in any service is its usefulness in assisting the troops on the ground”—an assertion he had also made to the General Board in 1919. The declaration may also have been a clear position against Army aviator William “Billy” Mitchell, who was just beginning to agitate for a unified and independent air service.

The first half of Cunningham’s article is a brief history of Marine aviation to date, emphasizing its small size prior to 1917 and detailing how it came to staff the aerial patrol bases in the Azores and Miami and become part of the NBG. He gave plenty of detail on what the Marine Day Wing did accomplish during the war and went on to note the detachments sent to Haiti and the Dominican Republic in 1919—and that the brigade commanders in both places have been “very complimentary” of the aviators’ work. He suggested various ways in which aviation could assist troops in the future, a list that is copied almost verbatim from the list of duties in the CNO’s July 1 letter. He expressed confidence that, by working with the ground forces, aviation would begin to show the ground forces “that we can contribute in a surprising degree to the success of all their operations.” This, however, would be Cunningham’s last direct influence on Marine Corps aviation.

In December 1920, Cunningham was relieved as Director of Marine Aviation and sent to command the squadron in the Dominican Republic. Then, in July 1922, Cunningham turned over command of the First Air Squadron and left Marine Aviation in accordance with a policy he himself had promoted to ensure that aviators did not become too isolated from the rest of the Corps. In 1928, Cunningham wanted to return to aviation duty. He was told there were no administrative positions open. If he wanted back into aviation, he would have to do so as a flyer: pass the physical and take some refresher training.

Unfortunately, before he could formally request new orders, he was sent to Nicaragua, where the Marine Corps was sending as many Marines as it could to help control the political violence ahead of contentious national elections. While there, Cunningham contracted a tropical disease that saw him medically evacuated back to D.C. on a hospital ship. Health problems dogged him for the rest of his life, preventing him from taking up flying again. Cunningham retired from the Corps in 1935 without ever returning to aviation and died in 1939.

Cunningham’s influence, however, would remain with Marine aviation well past his leadership assignment, particularly in his desire for the close coordination of Marine aviators and ground forces and his assertion that aviation only existed to help the troops. Cunningham’s influence is reflected to this day in the six functions of Marine aviation as taught at The Basic School: Offensive Air Support, Anti-Air Warfare, Assault Support, Air Reconnaissance, Electronic Warfare and Control of Aircraft and Missiles. Each of these functions has a greater or lesser coordination between air and ground forces, but all are aimed at ensuring that the aviators’ efforts make the troops’ tasks easier, whether that is offense, defense or force sustainment. Despite having vacated the senior leadership role for aviation in 1921, Cunningham’s belief in the raison d’etre for Marine aviation remains foundational more than a century later in the notion of the Marine air-ground team. It is this, rather than merely being the first Marine to report to aviation, for which he deserves the appellation “the Father of Marine Aviation.”

Author’s bio: Dr. Laurence M. Burke II is the aviation curator at the National Museum of the Marine Corps and author of “At the Dawn of Airpower: The U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps’ Approach to the Airplane, 1907-1917.”

He earned his Ph.D. from Carnegie Mellon University. After graduating, he held a postdoc position in the history department at the U.S. Naval Academy followed by several years as the curator of U.S. Naval Aviation at the National Air and Space Museum before joining the NMMC.