Terminology and Graphics

Posted on August 14,2019Article Date Apr 01, 2002

by the MSTP Staff

‘The mission, in particular, must be unmistakably clear so that once units become engaged all subordinate commanders can act with a unity of effort.’

-Capt Adolf Von Schell Battle Leadership

In his book, Battle Leadership, Capt Von Schell expressed the essence of mission tactics in maneuver warfare. When we assign missions to subordinates we must provide a task with a purpose and then provide the subordinate the necessary resources and time to accomplish the mission. Mission orders are only effective if they are clearly understood by the commander issuing them and, more importantly, by the subordinates executing them. Therefore, it is imperative that the mission and tasks are clearly understood and that the purpose endures contact with the enemy. Additionally, units must clearly understand the freedom of action and restrictions available within their delineated battlespace.

Words and graphics matter. Without the use of proper military terminology and symbology during planning and execution, the “unmistakable clarity” described by Capt Von Schell becomes impossible to achieve.

While the importance of proper terminology and graphics appears self-evident, Marine Air-Ground Task Force Staff Training Program (MSTP) often sees terminology loosely applied without an understanding of resource implications, use of nondoctrinal terminology, doctrinal terms “morphing” between higher and subordinate operations orders (for example, a tactical task to “seize” in a Marine expeditionary force order becomes “secure” in the division order), and the failure to use graphic control measures to clarify functional responsibilities.

References

Like any profession, the military possesses a unique vocabulary to address the complexity of the profession of arms. Similar to a lawyer or doctor, a military professional must have an understanding of some basic references as he applies his craft. These references form the foundation of our professional military vocabulary and must serve as “ground truth” in any discussion of tactical or operational planning. These publications include:

Joint Publication 1-02 (JP 1-02), Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, defines the approved terminology for general use by all components of the Department of Defense (DoD). In DoD Directive 5025.12, the Secretary of Defense has directed the use of JP 1-02 throughout the DoD to ensure standardization of terms. JP 1-02 should serve as the “first stop” in any search for doctrinal definitions.

Marine Corps Reference Publication 5-12C (MCRP 5-12C), Marine Corps Supplement to the Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, supplements JP 1-02 and contains definitions of Marine Corps terms, abbreviations, and acronyms not found in JP 1-02. MCRP 5-12C is designed to be used in conjunction with, JP 1-02.

MCRP 5-12A, Operational Terms and Graphics, is a dual-designated publication with the U.S. Army (Field Manual 101-5-1, Operational Terms and Symbols). This publication has terminology, acronyms, operational graphics, and symbology. The definitions in this reference are annotated where they are unique to one Service (Army or Marine Corps).

Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1-0 (MCDP 1-0), Marine Corps Operations, provides us with definitions of military terms and doctrinal explanations associated with Marine Corps operations. This publication is particularly useful because, unlike alphabetical order dictionaries, MCDP 1-0 organizes terms into subject matter areas: tactical tasks, types of operations, forms of maneuver, etc.

Tasks and Resources-Words Matter

Tactical tasks define the actions that commanders must take to accomplish their mission. They are relative to the enemy, terrain, and friendly forces. The following examples are not all-inclusive, but instead highlight tasks that are often used interchangeably or otherwise misused. Consider the difference in time, risk, and resources involved in each case.

Destroy or defeat? Destroy and defeat are each tactical tasks that focus on an enemy force. Destroy is “a tactical task to physically render an enemy force combat-ineffective unless it is reconstituted.” The definition clearly focuses on inflicting material damage and/or casualties on the enemy force. The level of damage required to meet the criteria of rendering a force combat ineffective has many variables. Unit size, composition, disposition, training, tactics, logistics, and morale are some of the variables that must be considered and assessed. Destroy is a difficult task to achieve and very difficult to assess, especially if a percentage of destruction is specified (50 percent of a named brigade, etc.). Collection assets and analysis must be allocated for the commander to know when he has accomplished this task.

Defeat is a tactical task to:

. . . disrupt or nullify the enemy commander’s plan and overcome his will to fight, thus making him unwilling or unable to pursue his adopted course of action and yield to the friendly commander’s will.

Like destroy, this tactical task relates to enemy forces, but in the doctrinal definition of defeat, the key phrase is that the enemy is unwilling or unable to continue his adopted course of action. Instead of pure physical destruction, the aim is to apply enough resources to affect the mind of the enemy commander or the capabilities of the enemy force relative to the friendly force or terrain. The friendly resources applied to defeat the enemy could come in a variety of ways. For example, denying the enemy the ability to cross a particular bridge could nullify his ability to attack along an avenue of approach.

In summary, it normally requires less time and resources to defeat an enemy force than to destroy the same force.

Secure, seize, or clear? Secure, seize, and clear are all tactical tasks that focus on terrain. There frequently is confusion over the differences between these distinctive tasks. Secure is defined as:

. . . to gain possession of a position or terrain feature, with or without force, and to prevent its destruction or loss by enemy action. The attacking force may or may not have to physically occupy the area.

Seize is “a tactical task to clear a designated area and obtain control of it.” This definition illustrates “a task within a task.” The definition of seize, “to clear a designated area,” leads us to the definition of clear. Clear is defined as:

. . . the removal of enemy forces and elimination of organized resistance in an assigned zone, area, or location by destroying, capturing, or forcing the withdrawal of enemy forces that could interfere with the unit’s ability to accomplish its mission.

While all three tactical tasks relate to terrain, to secure an area potentially requires far less time and resources than does seizing with its imbedded requirement to clear enemy forces from an area.

Screen, guard, or cover? Security operations are designed to provide reaction time, maneuver space, and protection to friendly forces. The three types of security operations– screen, guard, and cover-are often misunderstood. While all three tasks focus on the friendly force, they differ greatly in their resource implications. Screen is a task “to observe, identify and report information, and only fight in self protection.” A unit with a task to guard must “protect the main force from attack, direct fire, and ground observation by fighting to gain time, while also observing and reporting information.” A unit with a task to cover operates apart from the main force to “intercept, engage, delay, disorganize, and deceive the enemy before he can attack the main body.” These three tasks are often misused. They are all oriented on protecting a friendly force, but again, the level of resources committed escalates from screen through guard to cover. Additionally, guard specifies a level of mutual support while screen and cover do not.

Purpose

In the context of maneuver warfare words take on a new importance. In assigning a tactical task to a subordinate unit, we effectively tell that unit “what to do.” We also need to tell them the purpose-“the why.” This is most clearly expressed as the object of the phrase “in order to.” The purpose provides the common understanding that facilitates unity of effort. It focuses resources on the commander’s end state-the vision of success. Together, the task and purpose form the subordinate unit’s mission. The purpose (with method and end state) makes up the commander’s intent-the key tool of maneuver warfare that promotes initiative in mission accomplishment.

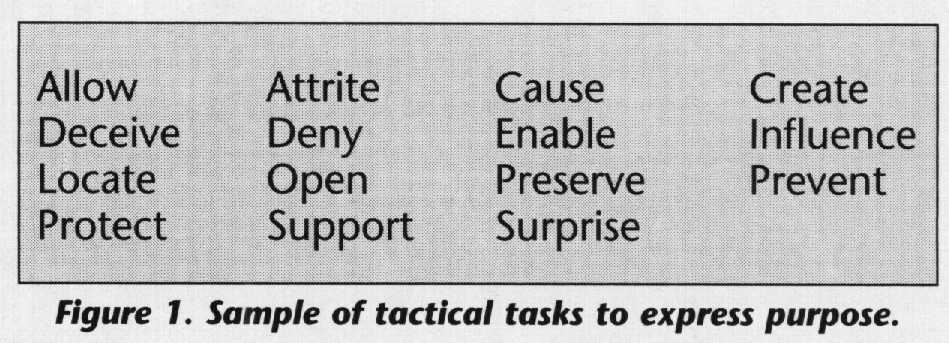

To be effective in these three roles the purpose has to be unambiguous and must endure beyond contact with the enemy. Figure I is a sample of words that may be effectively used to express the purpose of tactical tasks. The list is drawn from various sources and is not comprehensive.

The crucial point regarding the purpose of tactical tasks is that they must be clearly understood by all concerned. If the stated purpose is confusing-it must be clarified. Clarity can be added through an explanatory statement, “By deny I mean. . . .” The goal is shared understanding; common terminology is a tool to achieve this goal. To ensure this understanding the commander may want to add a glossary to the operation order or plan when nondoctrinal terminology is used.

Graphics

Precise terminology should be complemented by well-thought-out and understood graphics. Military symbology serves as our professional “shorthand.” Properly used, these graphics are a powerful tool for the commander and his staff. Graphics visually portray intent, tasks, and responsibilities. The old saying that “a picture is worth a thousand words” holds true in the area of military symbology. Consider the task of “attack along Axis Sword.” (See Figure 2.) While the words clearly portray the task, the visualization of this task is incomplete without graphically tying the task to the terrain.

The power of military symbology is often diluted by a lack of attention to detail. MSTP commonly sees incomplete development or understanding of basic control measures such as boundaries and fire support coordinating measures, failure to properly label control measures with the establishing agency and date/ time/group when the measure takes effect, and the improper depiction of on-order control measures. As a result, the fog and friction of war often starts with the operations overlay.

Conclusion

Tactical terms and the related graphics associated with military operations are our tools for communicating and directing the activities of our subordinates. As such, these words and symbols control resources and time and incur different levels of risk. As leaders and planners we are obliged to know what effects we want to have upon the enemy, the amount of resources we are willing to expend, and the risk we are willing to accept. We must then communicate this vision and direct our subordinates during execution. To accomplish this we have to properly articulate our vision by using doctrinally correct military terms and supporting graphics.

Precise terminology and graphics can help the commander generate tempo in planning and execution because subordinate commanders have a clear end state. On the other hand, improper terminology and graphics undermine unity of effort, generate confusion, and may take away from a common understanding, thereby degrading tempo and increasing the risk to the force.

Notes

>This article is part of a series of articles by the MSTP staff that addresses MAGTF operations and lessons learned- Readers may download copies of these articles on the MSTP web site <www.mstp.quantico.usmc.mil> under Publications/Team Positions.