by Col William J. Harkin

In 331 B.C. on the plains of Arbela, near present-day Mosul, Iraq, a contingent of Macedonian cavalry led by Alexander the Great changed the course of history by shattering the ranks of a numerically superior Persian force commanded by Darius III. The subsequent disintegration of the previously unbeaten Persian Army paved the way for the Macedonian king to subjugate the vast expanses of the Persian Empire. To military historians, strategists, and practitioners of warfare alike, the significance of this epochal battle exists within Alexanders generalship and tactical skill. However, unknown to most students of modern warfare is the influence this single engagement had on the evolution in the study and conduct of warfare.

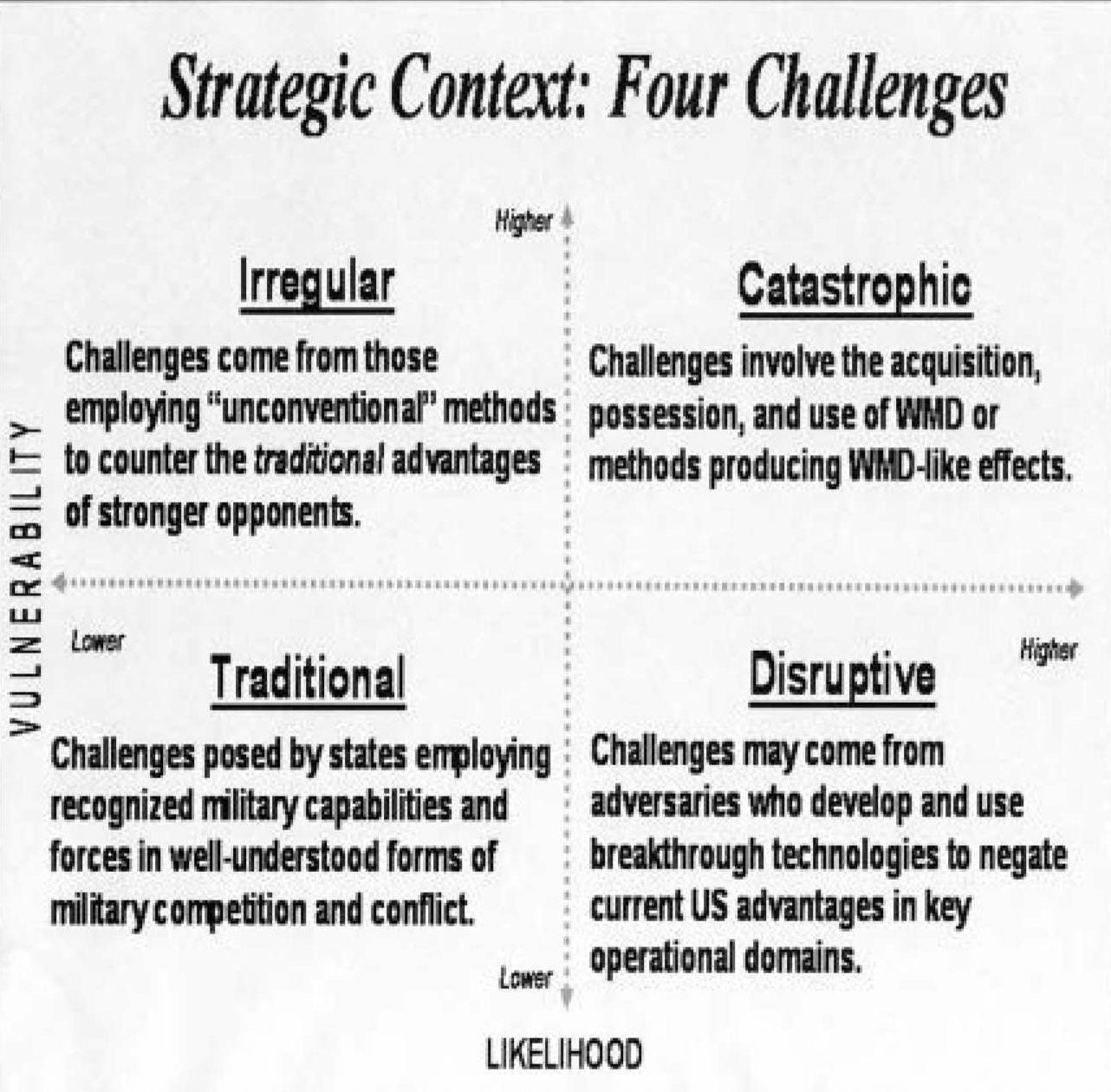

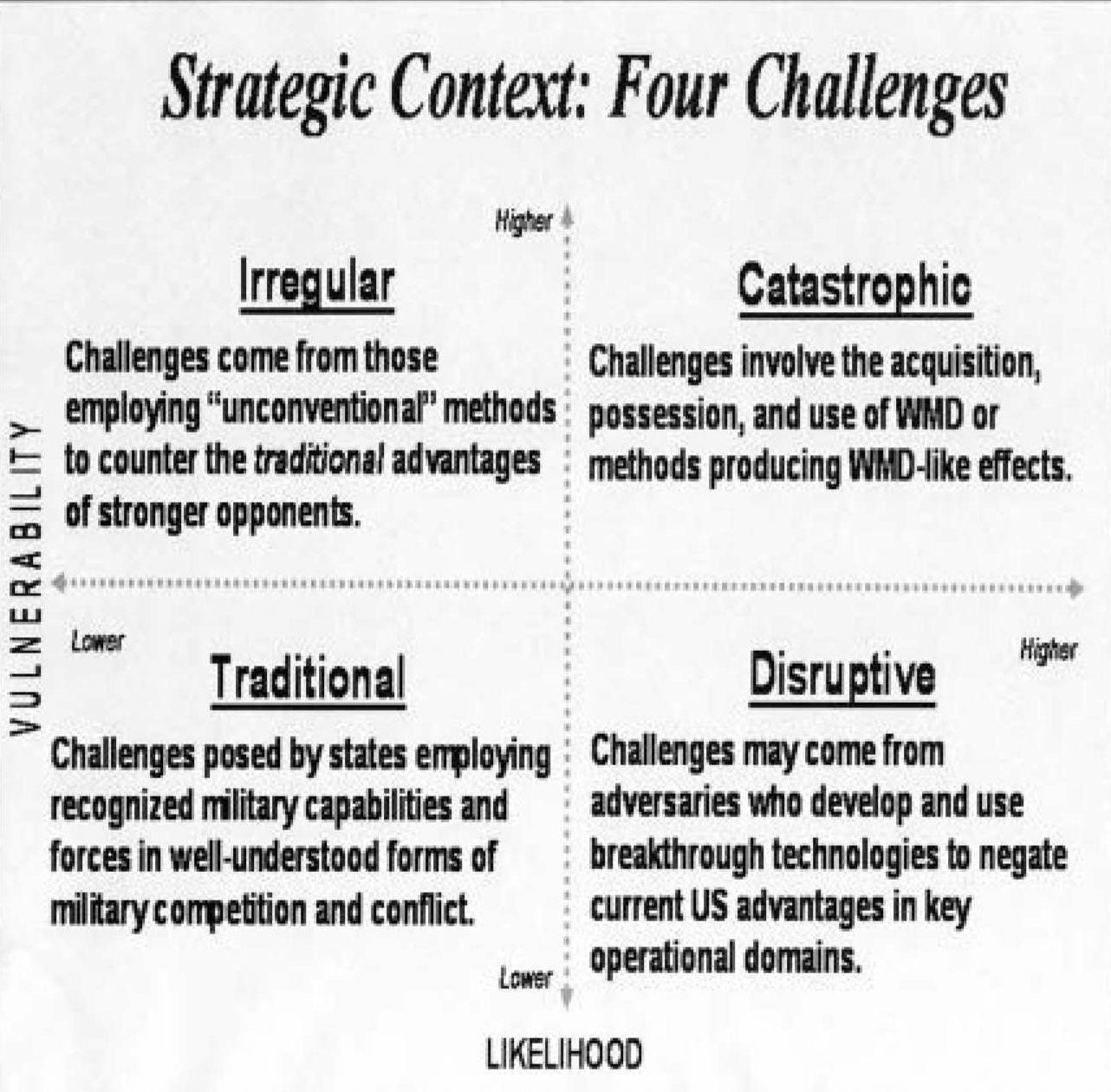

Our present-day security challenges are framed within the context of four environments – irregular, disruptive, catastrophic, and traditional warfare. (See Figure 1 .) Each of these environments presents distinct problems, unique circumstances, and differing solution sets. Our current maneuver warfare doctrine provides the foundation for developing a sound strategy to defeat an adversary operating within any of the four previously stated environments. As such, the purpose of this article is to study the contributions of three 20th century military strategists to the evolution of modern warfare and the development and continued relevance of maneuver warfare with respect to the most likely challenge, irregular warfare (IW).

Marine Corps Doctrine

Current U.S. Marine Corps doctrine as articulated in Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1 (MCDP 1), Warfighting, advocates maneuver warfare:

A warfighting philosophy that seeks to shatter the enemy’s cohesion through a variety of rapid, focused, and unexpected actions which create a turbulent and rapidly deteriorating situation with which the enemy cannot cope.1

Maneuver warfare acknowledges the chaotic, uncertain nature of warfare and espouses the need to operate within this realm. Implicit in uncertainty is the understanding that conditions are rarely permanent and, more than likely, are temporary in nature, whereby adaptability is critical to success. Additionally, this warfighting philosophy views the enemy as a system – a system, which if its cohesion is shattered then panic and paralysis will ensue and will ultimately result in the enemy no longer possessing the ability to resist.

Origins of Maneuver Warfare

The U. S Marine Corps’ adaptation of the maneuver warfare philosophy occurred with the inception of Fleet Marine Force Manual 1 (FMFM 1), Warfighting, in 1989. This publication provided the foundation for the Marine Corps’ current warfighting philosophy. In addition, Bill Lind’s Maneuver Warfare Handbook, published in 1985, served as a catalyst in catapulting the tenets of maneuver warfare to the war fighters of the day. Notwithstanding the contributions of Mr. Lind and other modern-day military theorists in the development of FMFM 1 and MCDP 1, three noted military strategists are responsible for the genesis of maneuver warfare and its underlying assumptions – J.F.C. Fuller, B.H. Liddell Hart, and John Boyd.

As mentioned previously, MCDP 1 states, “The aim of maneuver warfare is to shatter the cohesion of the enemy system.”2 It further asserts that maneuver warfare‘s “ultimate goal is panic and paralysis, an enemy who has lost the ability to resist.”3 The notion that the enemy is analogous to a system is largely a 20th century perspective. One of the earliest proponents of this belief was the renowned British military strategist and historian J.F.C. Fuller.

During World War I, as the chief general staff officer of the British Tank Corps, Fuller was instrumental in the development of armor tactics devised to break the stalemate of the static, attrition-type trench warfare along the Western front. After the Allies’ limited success at the Battle of Cambria in 1917 in which massed tank formations achieved only local tactical gains, Fuller set about designing a scheme to exploit the advantages of a mobile massed armored force against less mobile entrenched infantry units. As a result, Fuller formulated “Plan 1919.” Regarded as the seminal document with respect to tank warfare by armor enthusiasts, in actuality, Fuller’s plan was more of a concept than a detailed strategy. “Plan 1919” focused on a force capable of rapid movement, the ability to deliver a decisive blow, and the capacity to withstand an equally devastating riposte from the enemy; the desired end state being the disruption of the enemy’s ability to organize a coordinated counterattack. Accordingly, destroying the enemy’s command and control structure was essential to the success of the operation.

In “Plan 1919” Fuller mused that in the attainment of the strategic objective, which he stated as “the destruction of the enemy’s fighting strength,” two methods existed, “wearing it down (dissipating it)” or “rendering it inoperative (unhinging it).”4 He further elaborated that, unlike traditional attrition warfare, it was less costly and more effective to unhinge the enemy forces than it was to dissipate those forces. In order to unhinge the enemy, Fuller asserted that the attacker must destroy the enemy’s command to effect the disorganization of its forces.5 Fuller succinctly stated this in the following:

As our present theory is to destroy personnel so should our new theory be to destroy command, not after the enemy’s personnel has been disorganized, but before it has been attacked, so that it may be found in a state of complete disorganization when attacked.6

Paradoxically, he argued that the greater the number of reserves massed by the enemy, the greater the success as the objective was to paralyze the enemy by disrupting his ability to command and coordinate subordinate units regardless of their size. Fuller aptly referred to this concept as “brain warfare.”

Fuller developed this theory based upon his understanding of the March 1918 German offensive characterized by the use of heavily armed small units that sought to bypass enemy strongpoints and penetrate deep behind enemy lines. Referred to as “infiltration tactics,” Fuller then combined this recent knowledge with his historical analysis of Alexander the Great’s triumph over King Darius’ Persian Army at the Battle of Arbela in 331 B.C. Numerically inferior to the Persian forces, Alexander sought to focus the attack upon Darius himself, the Persian king, leader, and ultimate director and coordinator of the enemy. Alexander’s singular “decapitation-type” strategy proved successful and effected the disintegration of the Persian Army. Ipso facto, Fuller deduced that a highly mobile, concentrated, powerful force (rapid, focused) that attacks the command and control segment of an army would cause its rapid demise.

A friend and protege of Fuller, B. H. Liddell Hart, expounded upon his theory of brain warfare. Liddell Hart developed a military strategy that combined both the physical and psychological aspects of warfare. In the physical realm one exploited an enemy by placing or matching strength against weakness and by doing so sought a “line of least resistance.” Liddell Hart surmised that indispensable to this approach was the element of surprise (unexpected actions) focused on the psychological sphere or “the line of least expectation.”7 Referred to as the “indirect approach,” this method of warfare sought to dislocate the enemy, both physically and psychologically; i.e., hit them where they are the weakest and when and where they least expect it.

In this method, the physical effects, such as severing the enemy’s lines of communications or disrupting his dispositions, combined with the element of surprise, accentuated the psychological effects, in which the enemy commander felt cornered. A sort of checkmate was in place, as the commander did not possess a viable option; only defeat loomed ahead. In a sense, Liddell Hart delved further into the psychology of the enemy than Fuller and thus set the stage for more incisive study.

A latter 20th century military theorist, the late Col John Boyd, USAF (Ret), built upon Fuller and Liddell Hart’s theory of the psychological and physical element of the enemy and developed what we refer to today as maneuver warfare. As a former Air Force fighter pilot and military theorist, Boyd analyzed countless military battles throughout the ages and then synthesized the many lessons from these conflicts. He combined this study with his understanding of fighter tactics to create the famous OODA loop, arguably the foundation for maneuver warfare theory.8 Boyd viewed warfare as a time-competitive event in which the successor consistently acted in a faster manner over time; i.e., created tempo until the opponent’s will to resist collapsed. Implicit in this understanding is the continuous cycle of action-reaction between adversaries, which highlights the iterative nature of war.

On the surface, Boyd’s theory appears simplistic, yet the details of how he arrived at this conclusion reveal its complexity. In his studies, Boyd believed it essential to understand the interaction of and the bonds forged between the moral-mental-physical forces governed by the nature of warfare and to direct actions to severing and isolating those connections in order to defeat the enemy’s will to resist.

The moral forces consist of the emotional or the psychological arena whereby the goal is to promote courage, confidence, and cohesion within friendly forces and concurrently to generate fear, uncertainty, and alienation within enemy forces. The mental field refers to the intellectual acuity to grasp and understand a situation and determine a suitable course of action in a timely manner. Although not explicitly described in his writings, one can presume Boyd defined physical forces as those relating to material and objectives in relation to the enemy; e.g., force ratios, terrain seized, personnel captured, etc.9 In sum, Boyd asserted that a successor’s actions must be aimed and synchronized against all three forces in order to defeat an enemy’s will to resist. Boyd cogently and unambiguously stated the relationship between the three in the following:

Unless one can penetrate adversary’s moral-mental-physical being, and sever those interacting bonds that permit him to exist as an organic whole, as well as subvert or seize those moralmental-physical bastions, connections, or activities that he depends upon, one will find it exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to collapse adversary’s will to resist [create a turbulent and rapidly deteriorating situation].10

He further stated:

Morally-men tally-physically isolate adversary from allies or any outside support as well as isolate elements of adversary or adversaries from one another and overwhelm them by being able to penetrate and splinter their moral-mental-physical being at any and all levels [shatter the enemy’s cohesion . . . with which the enemy cannot cope].11

As one can see, Boyd’s analysis and subsequent synthesis explicitly identifies the bond between the three forces and furthermore asserts the criticality in directing one’s actions toward them in a holistic, comprehensive manner. Moreover, implicit in Boyd’s statements is the imperative to “control” the tempo of operations. Although the current definition of maneuver warfare states “rapid . . . actions,” speed of action does not equate to success in all instances. For example, while conducting counterinsurgency (COIN) operations, the execution of military offensive operations based upon the misperception that speed of action against a perceived military target without regard to the impact upon the population writ large may cause more harm than good.

Each of the three strategists viewed warfare through a prism containing the physical and psychological forces with Boyd further dissecting the psychological arena into moral and mental spheres or domains. Arguably, relative to the three strategists discussed, Boyd has engendered the greatest to the study of warfare, development, and the definition of maneuver warfare. Nonetheless, Liddell Hart’s and Fuller’s significant contributions cannot be overlooked. Whereas Boyd expertly described the need to “shatter the enemy’s cohesion” in the moral, mental, and physical spheres and the criticality in creating a “deteriorating situation with which the enemy cannot cope,” Liddell Hart and Fuller defined the need for “rapid, focused, and unexpected actions,” albeit predominantly in the physical and psychological domains.

Maneuver Warfare and IW

So with the understanding of the evolution of maneuver warfare, how do we apply this warfighting philosophy to current operations, such as IW? The joint operating concept, Irregular Warfare: Countering Irregular Threats, defines IW as:

… a violent struggle among state and non-state actors for legitimacy and influence over the relevant populations. Irregular Warfare favors indirect and asymmetric approaches, though it may employ the full range of military and other capabilities, in order to erode an adversary’s power, influence, and will.12

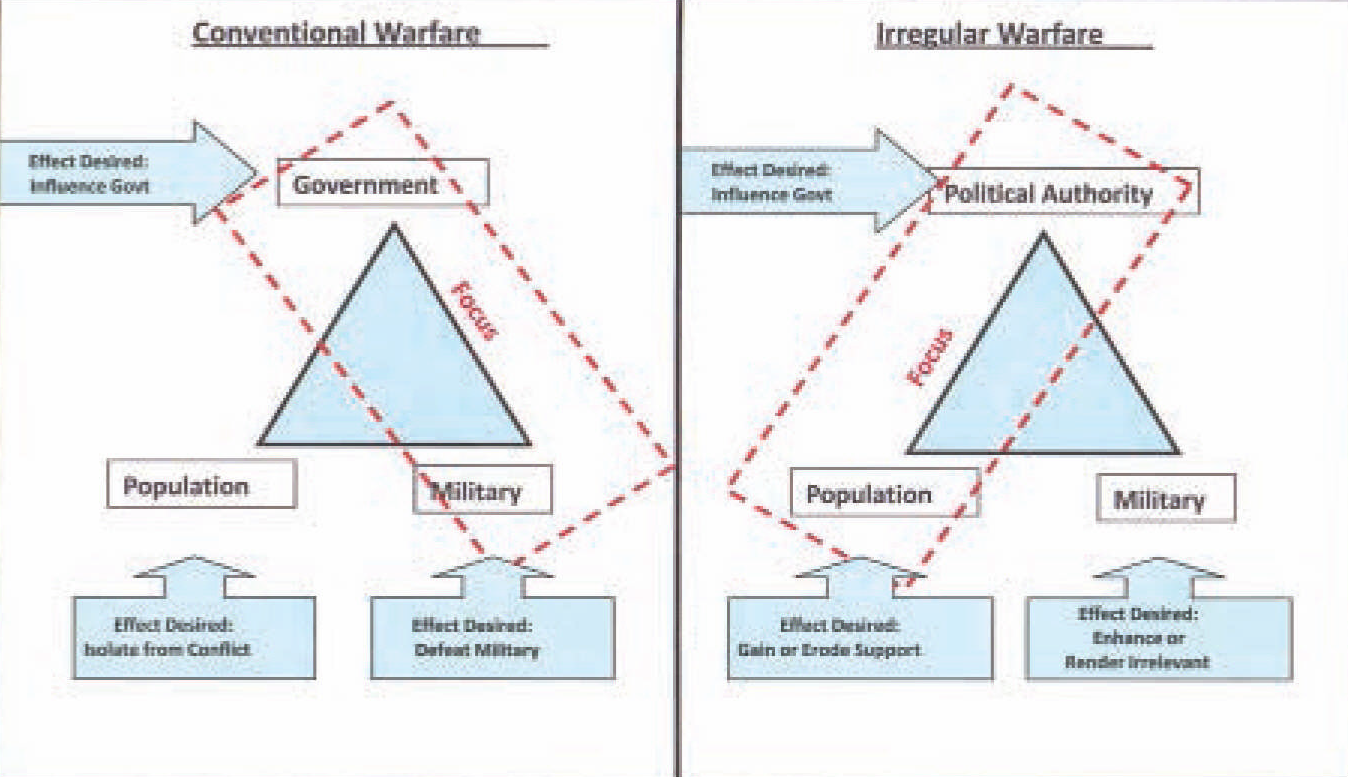

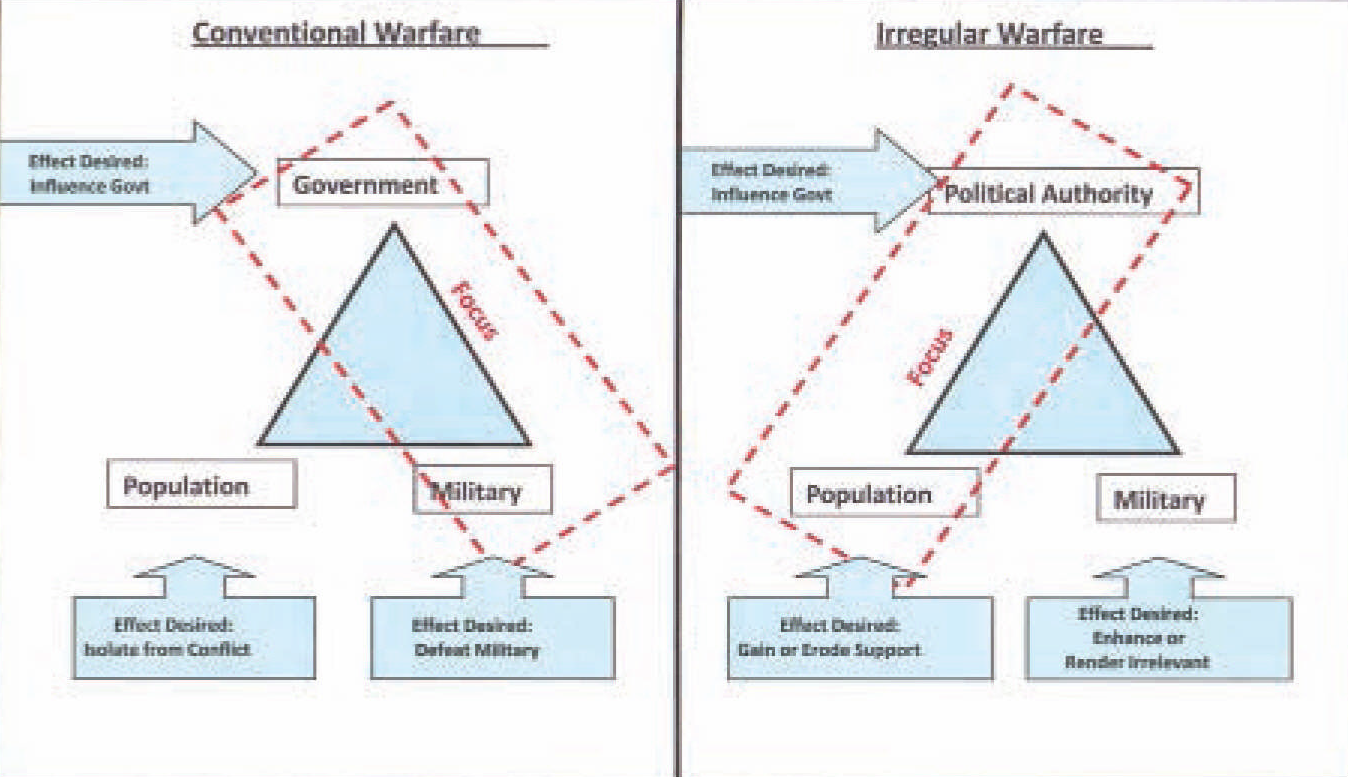

The Marine Corps’ Center for IW has adroitly pointed out the contrast between conventional conflict and IW in regard to Clausewitz’s paradoxical trinity.13 In Clausewitz’s concept of trinitarian warfare, three forces are constantly at work – the military, the government, and the population.14 In traditional or conventional conflicts with state versus state actors, the interaction between the military and the government prevails as our efforts are focused upon defeating our opponent’s military and thus influencing or compelling their government to cease resistance. Contrastingly, in IW the critical interaction occurs between the population and the government as the support or lack of support from the relevant population is intrinsically linked to the legitimacy of the government. (See Figure 2.) Furthermore, added layers of complexity are extant in IW as compared to conventional conflicts as there are by definition a greater number of participants, such as coalition forces, host-nation security forces, other government agencies, nongovernment organizations, etc. The increased number of participants involved, coupled with the intangible qualities and characteristics of gaining or eroding population support, presents an imposing challenge to those engaged in IW.

A way to approach this complex challenge is to view the forces at play in IW through the lenses of the moralmental-physical prism expounded upon earlier. For instance, while conducting COIN operations we should strive to mo rally-ment ally- physically isolate insurgent leaders, forces, and their supporters from the population while simultaneously directing actions that strengthen the moral-mentalphysical bonds between the relevant population, the government, and security forces. More specifically, we should endeavor to enhance unity, confidence, and legitimacy between the host-nation government, population, and security forces while concurrently promoting fear, uncertainty, and alienation between the relevant population and the insurgent group and within the insurgent group (delegitimize); developing and executing a plan in a timely manner that synchronizes disparate activities associated with COIN operations; and denying the insurgents sanctuary and support from the relevant population and external sympathizers.

Within the mental sphere, plan development necessitates the coordination between multiple dissimilar and unequal entities and the synchronization of unrelated activities. To overcome this conundrum, activities are grouped into common categories, such as economic development, governance, essential services, host-nation security forces, and combat operations/civil security operations.15 Commonly referred to as logical lines of operations, these activities permit planners to orchestrate disparate actions in a holistic manner and to ensure that interrelated activities do not produce outcomes that are counter to or deleterious to the desired end state.16

When applying maneuver warfare to IW and specifically COIN operations, it is paramount to define the roles and relationship of the moralmental-physical forces at play. Understandably, the three are inextricably linked regardless of the type conflict. However, when conducting COIN operations with a goal of enhancing the legitimacy of the host-nation government and eroding the cause of the insurgents, all activities must be assessed based upon their ability to morally isolate the insurgents. To this end, the role of the physical force or actions taken is subordinate to and supports the role of the moral force. The primacy of moral isolation over physical destruction of an insurgent group cannot be overemphasized. Many practitioners of warfare believe that it is antithetical to subordinate physical destruction of the enemy to moral isolation; nonetheless, should we fail to do so then we may find ourselves in a protracted engagement. While the moral and physical forces are supported and supporting, the mental force functions as an enabler and facilitates the desired end state by focusing efforts and controlling tempo of operations.

The continued relevance of maneuver warfare in current and future conflicts is indisputable; however, in order to successfully confront the exigencies of modern warfare we must perform the following:

* Clearly and unambiguously define the type of conflict we are involved in using the paradoxical trinity as a starting point, whereby all participants are assessed based upon their association with or support to the government, the military, and the population.

* Analyze friendly, neutral, and adversary forces or participants using the moral-mental-physical prism in order to establish the roles and relationships between the forces at play and to direct actions to develop and strengthen bonds or to sever and isolate existing bonds.

* Apply our maneuver warfare doctrine with an emphasis on the ability to rapidly adapt to a given situation while simultaneously having the foresight to control the tempo of operations.

As the challenges of the 21st century continue to emerge, develop, and mature, so too must our solutions, for just as the nature of warfare is immutable so the conduct of warfare is constantly changing. Consequently, critical to our success is the understanding of the changing relationships between the forces at play; if not, we will be forever mired in the old think of the past and unable to adapt to the changing environments of the future.