by Marinus

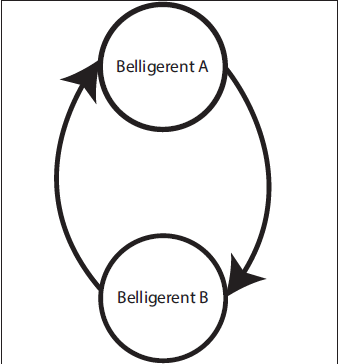

Warfighting steals a page from Clausewitz’s On War by proposing the Zweikampf, or “two-struggle,” as the essential, universal definition of war.1 It defines war as a violent clash between two independent and hostile wills—each trying to impose itself upon the other by force and constrained only by its own limits and the countervailing efforts of the other. In Clausewitz’s time, the term Zweikampf was used to describe wrestling matches, duels, trial by combat,2 and even the fights between Achilles and Hector before the walls of Troy. A critical insight of the term is that it is a serious mistake to think of the enemy as an inanimate object to be acted upon like an anesthetized surgery patient—a seemingly obvious point that has been violated repeatedly throughout history. Instead, the enemy is an intelligent will that does everything in its power to achieve its own objectives. Maneuverist No. 2, “The Zweikampf Dynamic,” (MCG Oct 2020), argues that the two-struggle is inherently nonlinear and that that nonlinearity makes war fundamentally uncertain, unpredictable, and frictional. It also argues that this way of thinking about war is foundational for, and may even be distinctive to, Marines. (See Figure 1.)

The Zweikampf implies cohesion within each fighter and symmetry between fighters. Once we involve more than a single actor on each side, however, we find ourselves dealing with alliances or coalitions of various sorts—whether between states, within states, or among actors of any kind. This, of course, leads to Sunzi’s notion of attacking alliances and Boyd’s of attacking cohesion. Moreover, while belligerents in the two-struggle may have different strategic objectives and may employ different capabilities in different ways, the Zweikampf is essentially symmetrical in that both belligerents are attempting to get their way by applying force directly against the other. This certainly seems to be true for Clausewitz, as both metaphors he uses when introducing the concept, wrestling and dueling, are symmetrical.3 Clausewitz was an observer of the Napoleonic wars after all, and so his natural focus would be on regular armies maneuvering directly against each other. The assumptions of cohesion and symmetry do not in any way weaken the concept of the two-struggle.

Is the Zweikampf really universal after all?

But after witnessing nearly twenty years of warfare in Afghanistan and Iraq, we cannot help but question if the Zweikampf is a universal construct after all. It strikes us as something of a stretch to argue that the two-struggle has applied cleanly to those conflicts—as well as to many others throughout history. Perhaps the Zweikampf applies more narrowly to what we now call regular warfare, and there is an entire other category of war that the Zweikampf construct does not capture in its essence and for which another construct might provide more and better insights. We speak of various forms, now most commonly called irregular warfare, in which the belligerents, in addition to fighting each other, must also struggle for control over a contested population.4

The Dreikampf

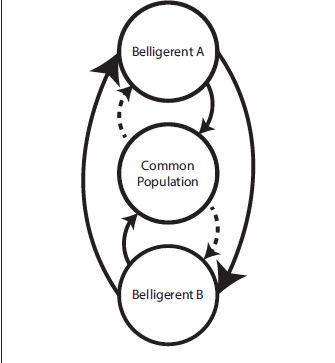

For these other forms of warfare, we propose a construct we will call the Dreikampf, or “three-struggle,” in which the third actor in the struggle is the common population that both belligerents struggle to impose themselves upon in addition to struggling to impose themselves upon each other. (See Figure 2.)

Dreikampf as we propose it is not simply any conflict with more than two combatants—which is actually most wars. Wars with multiple combatants are commonplace, but they will tend to coalesce into two-struggles as the various combatants align into two camps based on their overlapping interests. The alliances may be relatively stable and enduring, as were the Allied and Central Powers in the First World War, or they may be continuously shifting, as with the various actors in the Syrian conflict today. But the point is that at any particular time and place, the multifaceted struggle will tend to coalesce into two camps, and the Zweikampf dynamic will prevail. As an example, the Chinese Nationalists and Communists fought for control of China in the 1930s. In 1937, Japan invaded, adding a third actor to the struggle, and the two Chinese factions, irreconcilable enemies up until that point, formed a united front against Japan. The Nationalists and Communists eyed the other with suspicion, and even clashed occasionally, but generally cooperated in the defeat of Japan, which both saw clearly as the greater, common threat. Once Japan was defeated, they returned to fighting each other in an existential struggle the Communists eventually won in 1949.

The Nature of the Three-Struggle

The characteristic essential for a three-struggle as we have proposed is the existence of a common, contested population that seeks to maintain its independence from either of the belligerents. The existence of the Dreikampf in no way invalidates the key lessons of the Zweikampf but rather is additive to them—or, more accurately, multiplicative. The nonlinearity that leads to unpredictability and friction in the Zweikampf is also inherent in the Dreikampf—only much more so. The simple addition of a third variable to the equation multiplies the complexity; we know from physics that, in contrast to two-body problems, three-body problems do not submit to closed-form solutions and in fact are chaotic under most conditions.5 (The classic demonstration of scientific chaos, which Clausewitz almost certainly witnessed, is a magnetic pendulum suspended over three magnets: the pendulum follows an erratic and seemingly random path, pulled by the three magnetic fields, sometimes captured briefly by one of them before careering off wildly again, never repeating the same path.) This may help explain why so many such conflicts historically have defied ultimate solution and instead required prolonged management over time.

More important than the addition of a third independent will to the struggle is the fundamentally different nature of the population from the other two belligerents. We are not fans of the term asymmetrical warfare to describe different operational approaches, but here the relationships genuinely are asymmetrical. Where the relationship between the two-struggle belligerents is essentially symmetrical, as we have said, the relationship between each belligerent and the population is far from it—and this diversity increases the complexity and difficulty even more. The interactions among the three interlocked wills are more varied, and these greater degrees of freedom are a primary driver of complexity. (See the discussion of complexity in Maneuverist No. 3.) The population generally does not attempt to impose defeat on either belligerent through force because it usually possesses neither the capability nor the interest. It must be subtler and more indirect, employing influence rather than coercion. Most often, its aim is not to impose itself on a belligerent but to maintain and maximize its own freedom of action vis a vis that belligerent. Basic power theory says that all power relationships are reciprocal even if they are far from balanced. Even a prison population finds ways to exert influence against its armed guards, and so it is with the Dreikampf.

Finally, populations are not likely to be as monolithic as the two other belligerents, nor as consistent and coordinated in their actions.6 The contested population almost always will comprise multiple subgroups, each with different, if potentially overlapping, objectives, means, and methods. Again, this variability only tends to increase the complexity of the dynamics.

The three-struggle itself may be transitory, as once the contested population falls under the control of one belligerent or the other the conflict reduces to a multifaceted Zweikampf, as discussed above. But we suggest that, even if sometimes transitory, the three-struggle is an important concept because it manifests different dynamics than the two-struggle.

The Zweikampf is a deceptively simple model that produces surprisingly complex dynamics. The Dreikampf is a more variable and complicated model that multiplies that complexity geometrically. It is not surprising, therefore, that Western armies traditionally have shown little interest in Dreikampf conflicts, after which they are quick to return to preparing for “real war”—which of course means Zweikampf. We have seen this in the U.S. military. Most recently, we seem to have forgotten the hard lessons learned in the Vietnam War—“No more Vietnams!”—only to have to go through the pain of relearning them in Afghanistan and Iraq. We do not dispute the rise of potential peer adversaries today, but we cannot help but wonder if the desire to return to “real war” is contributing to the current single-minded focus on Great Power conflict—or to the belief that it will be strictly regular. Even in future warfare against peer adversaries—even totalitarian states—we suggest that the popular will is likely to exert itself directly. Hostilities are not likely to end with the defeat of an enemy state’s regular military forces. In an age when societies are simultaneously fragmented and empowered by the democratizing effects of information technology, populations are less likely to abide by the decisions reached by their governments or the results achieved by governmental military forces—as we witnessed in Iraq in 2004. Dreikampf is not likely to disappear, no matter how hard we may wish it. To paraphrase a popular life quote: “Dreikampf is what happens when you’re planning for Zweikampf.” We suggest that we ignore that at our own peril.

Dreikampf and Insurgency

Dreikampf is not synonymous with insurgency/counterinsurgency, although we suggest it may provide insight into the dynamics of many such conflicts, just as the Zweikampf continues to provide insight into regular warfare. Not all insurgencies are three-struggles. Nor do all insurgents employ irregular methods, although many do because they lack the resources to engage the established order on an equal footing, at least initially. Although not often thought of as such, the American Confederacy, for example, was an insurgency seeking to establish its independence from the United States. But the American Civil War was a classic Zweikampf fought primarily using regular warfare. The Confederacy could fight this way because it was able at the outset of the conflict to appropriate the national warmaking resources located in the Southern states.7 The Civil War was not a three-struggle because the American people were not an independent entity (or a unitary one). When Gen William T. Sherman cut a destructive swath through the South on his March to the Sea in 1864, he understood that the population of the South was an integral part of the Confederacy and not a separate thing. No application of population-centric counterinsurgency doctrine would have won the Southern populace over to the Northern cause. The same was true of the Northern population.

Conversely, not all three-struggles are insurgencies. The War in Afghanistan was a conflict between the United States and the Taliban in which the Afghan population, at least initially, had little interest beyond wanting to be left alone to pursue its interests without the interference of any national government.

The point is that the proposed Dreikampf is not simply synonymous with insurgency or even narrowly a construct of insurgency. Not all insurgencies are Dreikampfe, and not all Dreikampfe are insurgencies. There is, however, a class of insurgency in which the popular will is central, protracted popular war,8 which is common enough that it is synonymous with insurgency in many people’s minds. Which is another way of saying that Dreikampf will remain a frequent challenge in the future.

Implications of the Dreikampf

The key insight of the Dreikampf is this: Just as the Zweikampf asserts that the enemy is not an inanimate object to be acted upon, so the Dreikampf asserts that neither is the population an inanimate object to be controlled or influenced at will. The population is not merely “human terrain” to be fought through or a prize to be won, but rather is a third independent, or at least semi-independent, will with its own interests that do not align with either belligerent. (If they did align with one of the belligerents, the conflict would not be a Dreikampf.)

As with the Zweikampf, it is not merely the characteristics of the individual contestants in the three-struggle that give the conflict its essential nature but the even more complex and now asymmetrical interactions among the three. We suggest that this makes the Dreikampf dynamic chaotic and exceedingly challenging.

Importantly, the Dreikampf model is not necessarily an argument for a hearts-and-minds, population-centric counterinsurgency doctrine. One of the requirements the tripartite construct imposes on each belligerent is how much time or effort to devote to the other belligerent and how much to the population. For the latter, the question is how much effort, and what kind, to exert against either of the two belligerents. And for all parties, there is a question of how the two efforts relate to each other within the broader concept of operations.

One key implication is the critical importance of understanding the true dynamics of the conflict at hand. There are a few ways to go wrong. It is always an option—a temptation even—to treat a Dreikampf as a Zweikampf either by ignoring the contested population and focusing on defeating the enemy militarily or by treating the population as part of the enemy even when it is not. The former risks ignoring a potentially valuable ally, which may or may not be a fatal mistake. The latter likely will drive the population into the enemy’s camp, becoming a self-fulfilling prophesy. The converse mistake is to treat a Zweikampf as if it were a Dreikampf, wasting time and effort trying to win over a population that has already sided with the enemy. Similarly, it is a serious miscalculation to underestimate the population’s determination not to be controlled by either belligerent, wasting time and resources that could better have been put to defeating the enemy. In either of the last two cases, a tendency to try to win over a population that will not be won over seems to be a dangerous tendency of population-centric counterinsurgency doctrines. Some populations may not be co-opted, only subjugated.

The overriding insight of the Dreikampf model, again, is the importance of recognizing the population as an independent will with its own interests and objectives, always maintaining the ability to adapt and surprise.

Conclusion

We have argued that Chapter 1 of Warfighting, “The Nature of War,” is the most important in the book because it establishes for Marines a common and compelling understanding of the nature war, which is a fundamental prerequisite for determining how to fight. Foundational to that description in Warfighting is the concept of the Zweikampf with all its implications. Warfighting starts by asserting the Zweikampf and then proceeds to discuss its subject consistently in that context. Nowhere does it address specific forms of warfare, such as regular and irregular, but many readers over the years have inferred a regular warfare bias. The Zweikampf model itself may help explain that interpretation. (While it may have attempted to address war in timeless and universal terms, FMFM/MCDP 1 was a product of the Cold War era, as were most of its early readers.)

We sense from recent and historical operational experience that the Zweikampf may not be a universal model after all, and we wonder if it may be time to expand the taxonomy of war to acknowledge a class that is better described by the Dreikampf model. In fact, an increasing number of Marines who are not products of the Cold War seem to be arguing, on these pages and elsewhere, that MCDP 1 as written does not meet current requirements. If Warfighting is to be revised, we suggest that this issue might be worthy of consideration.

Notes

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. and ed. by Michael Howard and Peter Paret, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984).

- An obsolete method of Germanic law to settle accusations in the absence of witnesses in which two disputing parties fought in single combat, and the victor of the fight was proclaimed to be right.

- Ibid.

- “Irregular warfare: A violent struggle among state and non-state actors for legitimacy and influence over the relevant population(s). Also called IW,” DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, s.v. “Irregular Warfare,” available at https://www.jcs.mil.

- Deterministically chaotic. See Maneuverist No. 3, (MCG Nov20).

- Not that the armed belligerents will necessarily be all that coordinated.

- Insurgencies in which the insurgent and establishment fight on more or less equal, conventional terms are often called civil wars. (E.g., the American Civil War.)

- See Bard E. O’Neill, Insurgency & Terrorism: Inside Modern Revolutionary Warfare, (Dulles, VA: Brassey’s, 1990).