By Maj Ian T Brown

In February, I was privileged to attend the Force Development–25 Innovation Symposium. In two exciting days of lectures and workshops, everything from refining Expeditionary Force 21 to mobile 3D printers to autonomous nanobots building their own autonomous drones was scrutinized with pioneering eyes. Yet curiously absent from this soup-to-nuts assessment of all things Marine Corps was one item: Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1 (MCDP 1), Warfighting. Why? If we are serious about institutional innovation, how can we ignore the engine that drives everything else?

About now, I can hear accusations running from presumptuousness to heresy. Since 1989, Warfighting has been the muse guiding combat operations from DESERT STORM to ENDURING FREEDOM. Much in the Marine Corps has changed, but Warfighting remains our northern star. Gen Alfred M. Gray, among our most innovative commandants, lent it the full weight of his office. Brilliant thinkers like John Boyd provided its intellectual foundations. John Schmitt, a master of analysis and synthesis, wrote it. Do I think I could do better?

I don’t claim to be John Boyd or Gen Gray. But—risking even greater presumption—I think they’d acknowledge the value, in principle, of giving their work a fresh look. Boyd did not believe in closed systems or “final” theories, observing that if you stuck with Clausewitz as your theoretical model, your mind hadn’t moved beyond 1832.1 Almost as soon as Fleet Marine Force Manual 1 was published, Boyd called Schmitt and outlined ways to improve it.2 Indeed, thinking that Warfighting hasn’t changed since its inception is mistaken. In 1997, Gen Charles Krulak enlisted Schmitt and Boyd to revise it extensively. In MCDP 1 (Warfighting version 2.0), Krulak’s thoughts on doctrinal evolution were clear:

Military doctrine cannot be allowed to stagnate, especially an adaptive doctrine like maneuver warfare. Doctrine must continue to evolve based on growing experience, advancements in theory, and the changing face of war itself.3

In less than a decade, Warfighting was published and then revised. Yet two decades later, it remains untouched. In that timeframe, the Marine Corps has been transformed by the Information Age, fought two major wars, and now faces a geopolitical landscape utterly unlike that of the late 20th century. It is a world where materiel revolutions are no longer exclusively ours, leaving thought as the last realm open to exploitation.4 And yet, to paraphrase Boyd, our institutional philosophy hasn’t moved beyond 1997. I suspect sages like Krulak and Boyd would agree that reassessing Warfighting is a tad overdue.

In that spirit, I humbly offer some ideas for refining certain aspects of MCDP 1. My list is not comprehensive, nor do I argue that it is always right. Rather, I hope to generate thought and discussion as part of our institutional recommitment to innovation. If everything is on the table, our warfighting philosophy should not escape scrutiny.

Methodology

My suggestions follow the chapter structure within MCDP 1. I’m not offering wholesale replacement of text but will instead bring up major themes as points of departure for discussion. I cover only Chapters 2 through 4; Chapter 1 remains a brilliant synthesis of war’s nature, and I would not dare tinker with it. Finally, I’m approaching the manual from the framework outlined by Dr. Charles Oliviero in his model of “war-centered military theory.”5 This model differentiates between “philosophy,” “theory,” “strategy,” and “TTP” (tactics, techniques, and procedures), which are often misunderstood and erroneously interchanged. Per his model,

… philosophies are the underlying sets of beliefs upon which a society, including its armed forces, bases all that it does. Theories are compilations of principles and premises to aid in understanding.6

Are You Enjoying this Article?

Join MCA&F today to receive monthly editions of Leatherneck Magazine and the Marine Corps Gazette.

Both Gens Gray and Krulak described Warfighting as a philosophy, with the publication defining that philosophy and teasing it out into “Marine Corps theory.” Capstone doctrine should operate at those levels, and some of my offered amendments remove aspects of the manual that go below them.

Chapter 2 – The Theory of War

“Levels of War.”7While Warfighting hints at the Information Age impact on compressing levels of war, the evidence of two decades of conflict demands that we reassess both the levels and degree of compression. Warfighting illustrates that the traditional levels—strategic, operational, and tactical—sometimes overlap, with small unit tactical decisions having strategic effects.8 It also notes that above military strategy lies the level of national strategy;9 omitting further discussion of national strategy implies that such lofty goals are of little interest to the frontline warrior. If the last 20 years taught us anything, it is that the Information Age has flattened the levels of war such that one is almost indistinguishable from the other; that there are higher levels that the frontline warrior must comprehend; and that our “strategic corporal’s” actions can directly impact the Nation’s highest goals. This flattening is depicted in Figure 1, a model adopted from the works of John Boyd and Emile Simpson.10

From the abuses at Abu Ghraib to the Madrid train bombings, it is clearly no longer sufficient to say that tactical actions have “strategic” effects; rather, in the seconds required to upload a picture or video to the Internet, the repercussions of tactical actions are catapulted to the top level of national leadership and radically alter national goals.

Yet the consequences of this flattening are not wholly negative. In the Information Age, a handful of strategic corporals may achieve strategic or national goals that were once only accomplished by large armies or the combined resources of multiple Federal agencies. The key lies in both the strategic corporal and national leadership recognizing this new dynamic and understanding what responsibilities each owes the other. This will be discussed further in the “grand ideal.”

“Styles of Warfare.”

Styles in warfare can be described by their place on a spectrum of attrition and maneuver. Warfare by attrition pursues victory through the cumulative destruction of the enemy’s material assets by superior firepower. On the other end of the spectrum is warfare by maneuver which stems from a desire to circumvent a problem and attack it from a position of advantage rather than meet it straight on.11

Were it ever possible to argue that “attrition versus maneuver” covered the full gamut of warfare “styles”—a tenuous argument, as labeling the style maneuver caused unnecessary confusion at the outset, and our maneuver warfare is less about dimensional movement and “more about how a commander interprets battlespace and then applies combat power to achieve a desired outcome”12—it is surely no longer possible today. The examples provided in MCDP 1 unintentionally demonstrate the narrow scope of such a spectrum: with the exception of the Combined Action Program in Vietnam, all feature conventional uniformed force-on-uniformed-force combat under a formal declaration of hostilities.13 That is not the world we live in now.

Conventional, irregular, asymmetric, catastrophic—the list of modern warfare styles could fill this magazine and still be incomplete. Nor is warfare restricted to the use of military force, as two Chinese officers pointed out at the turn of the century. Cyber war, trade war, ecological war, and a host of other methods can fall under the rubric of styles; thus contemporary war includes “using all means, including armed force or non-armed force, military and non-military, and lethal and non-lethal means to compel the enemy to accept one’s interests.”14 Today’s warfare is “beyond limits,”15 but unlike the total war of World War II, war “beyond limits” combines “ten thousand methods” to achieve one goal. It merges national, international, and non-state organizations; cross-domain solutions; and military and non-military means.16 It leverages the strategic corporal (or hacker, or aid worker) to give tactical acts national-level effects.17 It is a “street fight,” with each side fighting for its own reasons and by its own rules.18 It recognizes that “the struggle for victory will take place on a battlefield beyond the battlefield.”19 Today’s style is Russia hacking the State Department email system or sending “little green men” into Crimea and the Ukraine; it is China hacking records in the Office of Personnel Management and militarizing the South China Sea under the guise of “land reclamation;” it is Iran hacking into the computer system of a New York state dam and using American hostages to further its nuclear and ballistic missile ambitions; it is the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) using the Internet to radicalize and advise lone wolves in the conduct of complex terrorist attacks without requiring that the radicalized travel to ISIS-held territory for training. Today’s style is ten thousand styles, only a few of which cross into the domain of traditional military force.

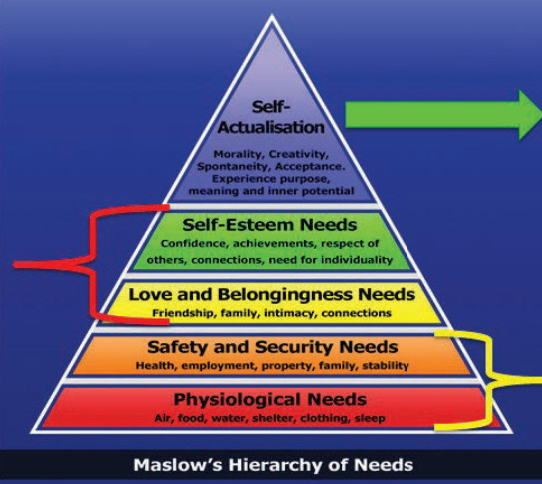

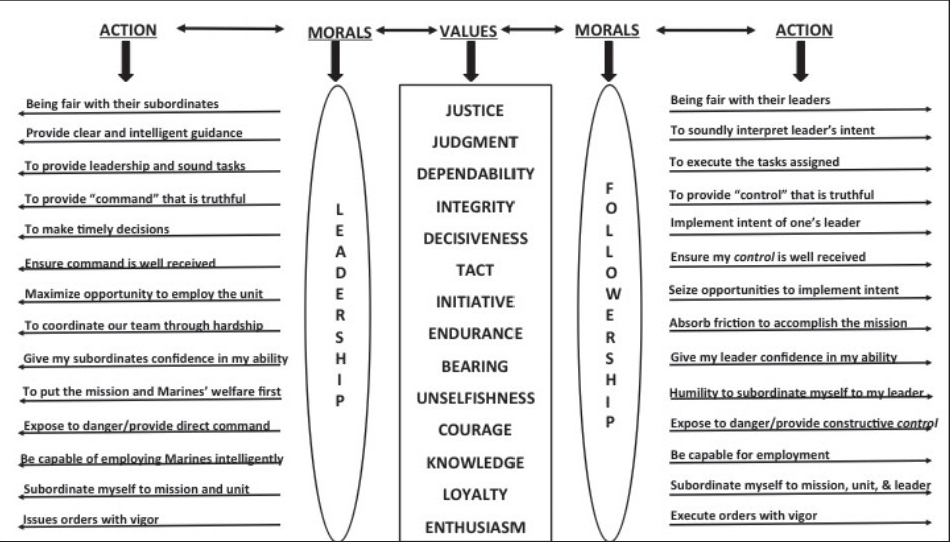

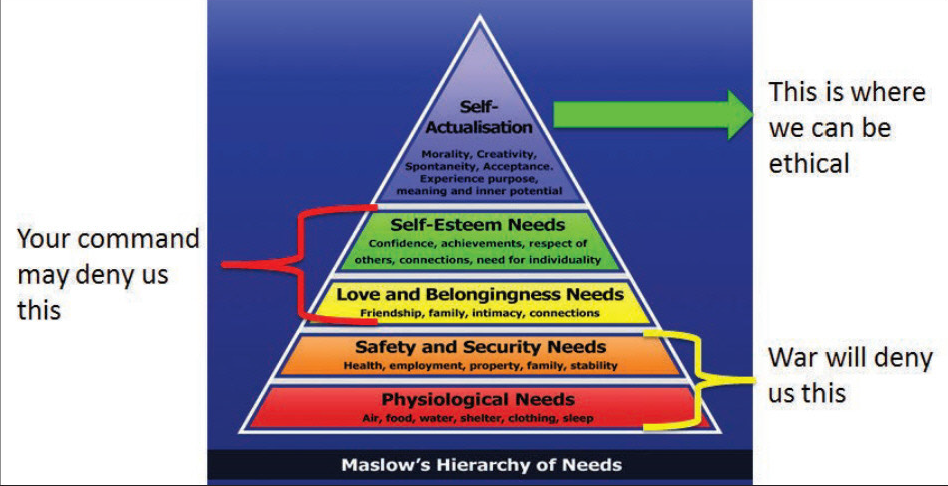

Determining which style we’re to face, and thus what style we should use to counter, comes through our orientation in preparing for war. But before moving on, let me point out one additional and uncomfortable attribute amongst these styles: the United States cannot assume materiel supremacy in any of them. Indeed, nations like China have poured resources into developing parity and/or superiority in other styles specifically to negate our conventional military supremacy (often the only style America worries about).20 Some might counter that the American military accepts the implications of materiel parity and retains supremacy in the quality of its individual warriors. Yet, given the global availability of genetic, robotic, and nanotechnology, we can’t even assume that we’ll have the edge in “building a better soldier.” Should America someday field warriors with physical and cognitive enhancements, our adversaries will likely be capable of fielding “enhanced” soldiers as well.21 With a level playing field in physical and mental factors, one realm remains open for exploitation in achieving superiority: the moral. This realm lies beyond nukes and neurons; its intangibility means it cannot be hacked, spliced, or enhanced with nanobots. But it can be manipulated, and the “ten thousand combinations” of styles enable this. Thus, the Marine Corps should aim to fight in the realm of moral warfare, and I elaborate on this in Chapter 4. First, however, we will explore two complementary elements that should be included in a modern theory of war: a theory of deception and the “grand ideal” or strategic narrative.

“Surprise and Boldness.”22 MCDP 1 suborns deception as one element of many in the category of surprise, with surprise itself a mere sub-element of generating combat power. Looking at today’s adversaries and today’s world—in which combat power is merely one card of many played in warfare “beyond limits”—I believe this relationship is dangerously inverted. “Warfare is the Way of deception … [one] gains victory through the unorthodox [ch’i],” as war’s first master stated 3,000 years ago.23 How did we lose sight of this? Any theory of war should include a theory of deception, of the “unorthodox;” yet the American military traditionally employs deception on an ad hoc basis, tossed aside when no longer needed. This is not the case among our adversaries today, all of whom ingrain deception into their own philosophical and theoretical frameworks.

With Sun Tzu, I have already touched on China; since the mid-1980s, Chinese defense thinkers have shown renewed interest in their nation’s classical military writings as they seek unorthodox ways to counter American military superiority.24 Aside from the instances of hacking and corporate espionage that we’re aware of, Chinese institutional deception rises high enough to obfuscate their real levels of defense spending.25

Radical Islam has its own deception modality—taqiyya— grounded in Shari’a law and derived from Muhammad’s assertion after the Battle of the Trench that “war is deceit.”26 Taqiyya is a complex concept—it was originally developed in Shi’ite communities to avoid persecution by Sunni Muslims—but its definition now encompasses any active deceit used by the faithful to gain advantage over non-believers. As all schools of Islamic jurisprudence have validated it, Sunni radicals like Osama bin Laden have no compunction using taqiyya in their operations against the West.27 Yet Iran (appropriately, as the theological home of taqiyya) has raised the concept to high art in its international dealings. Taqiyya, kitman, khod’eh, taarof, and a host of other concepts related to deception and disinformation enjoy long usage in Persian Islamic thought, justifying everything from financing terrorist operations abroad to masking the extent of the Iranian nuclear program at home.28

But Russia has arguably the most refined theory of deception. For decades, Russia practiced what is popularly known in the West as maskirovka, or “concealment.” This is a poor translation of the term, and a tribute to Russia’s employment of deception that maskirovka remains misunderstood. Its definition has evolved significantly since first employed, and today it is a subset of the broader Russian concept of voennaya khitrost, or “military cunning/stratagem.”29 As with taqiyya, voennaya khitrost covers not only passive measures but active steps taken to cloud and bend an enemy’s perceptions. Most importantly, Russia has long viewed deception as a critical combat support activity to be taught to leadership cadres from military schools to the Defense Ministry and integrated into planning from the tactical to the grand strategic levels.30 Russia’s recent Crimean and Ukranian expeditions bring the power of its deception operations into stark clarity.31

Today, we face adversaries for whom deception is not an “oh, by the way” function but a key component of the philosophies each uses to achieve its national goals. Across decades, China, Russia, and Iran have developed deception modalities that are entrenched in their culture, practiced in a whole-of-state approach, and integrated within their militaries at all levels. Their approach is not merely passive, seeking to hide their own capability. Take Russia in the Ukraine: Russia so corrupted and corroded the information flowing into their adversaries’ decision-making apparatus that both the Ukraine and European Union actively contributed to Russia’s own ends. Such unconscious collaboration goes well beyond making an adversary “act in a manner prejudicial to his own interests.”32 We must elevate deception to the same level in our warfighting theory. While the whole-of-state approach requires buy-in beyond the Marine Corps, there is no reason we can’t implement a whole-of-institution approach on our own. The Information Age offers myriad new opportunities to deceive an adversary across the five domains and in his own mind. I offer some suggestions for this in the conclusion.

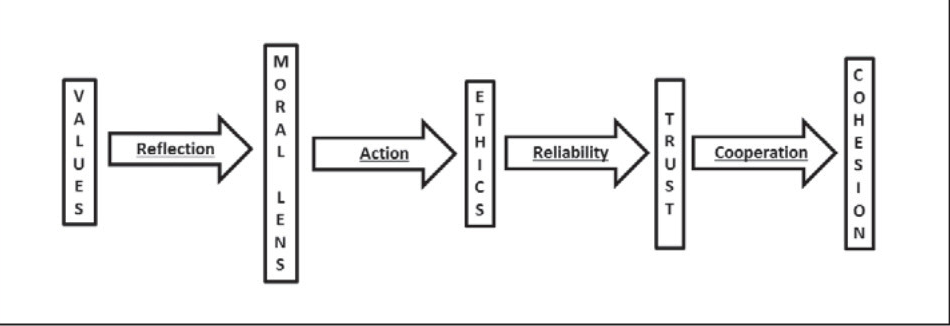

Looking at deception, one sees that it preys upon negative factors—menace, uncertainty, mistrust—in order to “pump-up friction … to breed fear, anxiety, and alienation” within an enemy.33 While deception may degrade or spoof some of the enemy’s physical systems, its greatest impact lies in corroding the enemy’s “spiritual” systems, his moral cohesion. The obverse of this negative, enemy-focused moral attack is the positive, self-focused moral amplifier Boyd labeled the “grand ideal.” This concept integrates the positive moral factors of insight, initiative, adaptability, and harmony into a “unifying vision … used to attract the uncommitted as well as pump-up friendly resolve.”34 Whereas deception seeks to corrode and corrupt an enemy’s moral cohesion, the grand ideal engenders friendly cohesion, acting as a spiritual anchor while allowing one to adapt and thrive to changing circumstances. The Nation’s leaders generate this positive vision, using it to “surface courage, confidence, and esprit, thereby make [sic] possible the human interactions needed to create moral bonds that permit us, as an organic whole, to shape and adapt to change.”35

An esoteric concept, Emile Simpson recently laid out a more pragmatic application of Boyd’s ideal which Simpson labels the “strategic narrative.” One’s grand ideal or narrative comes down to an explanation of actions crafted to persuade people of something, and which is tailored to an audience.36 In modern conflict with flattened levels of war and a global stage connected by digital communications, this narrative must be customized for each audience—friendly, enemy, and indifferent—while internalized for execution by all players from the national leadership down to the strategic corporal. Figure 2 shows this model, illustrating how the narrative is modified for audiences at lower levels of war while remaining nested in the larger ideal.37

As with Boyd, the power of Simpson’s narrative comes from several components: a permanently aspirational moral component, or ethos; historical association, drawn from and tailored to the experiences of each audience; and confidence in one’s vision, values, and intentions.38

Simpson adds a crucial component to this narrative absent from Boyd’s construct: a feedback mechanism from the strategic corporal to the Nation’s leadership. The grand ideal is our Nation’s “desire;” and while it is well and good to push that desire down to the tactical level—ensuring that the least of the warfighter’s activities supports the national goal—national leadership needs a way to determine whether those desires are feasible when the rubber meets the road. War is a brutal judge of whether an idea works; leadership must be open to the realistic “possibility” assessment delivered up from the idea’s implementation at the tactical level (see Figure 1). Ideal and real must communicate with each other through all levels of war, with players at each level feeding into this cycle and keeping the gap between desire and possibility as small as possible.39

While the power of the grand ideal was understood in past conflicts—especially those driven by ideologies40—our recent operations applied it imperfectly. Its importance makes it central to preparing for war, which will be discussed next.

Chapter 3 – Preparing for War

In a book operating at the level of philosophy and theory, Chapter 3’s content feels out of place. Discussions on force planning and personnel management, while important, do not rise to either level; they are more suited to an appendix or different manual altogether. Instead, I’d offer that at the theoretical level, the key concept in preparing for war is orientation: on our enemy, but also—perhaps more importantly—on ourselves. MCDP 1’s Chapter 4 includes a brief discussion of orientation, but I believe it’s worthy of a chapter all its own.

The second “O” in his observation-orientation-decision-action (OODA) loop, John Boyd first defined orientation in Organic Design for Command and Control:

Orientation is an interactive process of many sided implicit cross-referencing projections, empathies, correlations, and rejections that is shaped by and shapes the interplay of genetic heritage, cultural tradition, previous experiences and unfolding circumstances.41

In The Essence of Winning and Losing, Boyd offered his only graphic representation of the concept (see Figure 3), which makes clear the criticality of orientation to the OODA process.42

Of the five “key statements” in the brief, distilling the most important concepts from Boyd’s 30 years of research, three deal with orientation.43 Could I “foot stomp” on paper, it would be here: orientation, with its inputs, outputs, and processes, was Boyd’s cornerstone for victory or defeat. On its surface, it does not seem a novel concept—Sun Tzu arguably captured its tenets thousands of years ago44—but Boyd’s was an understanding and implementation of orientation without parallel.

One may ask why orientation deserves such emphasis; after all, it sounds suspiciously like “problem framing” or “mission analysis.” It is much more than that: as it functions primarily in the moral realm, it remains our and our potential adversary’s last arena for achieving superiority. “Genetic heritage”—the physical makeup of one’s body and mind—can be enhanced; knowledge is vastly more accessible both individually and collectively in the Information Age.45 What’s left is how well we understand and exploit orientation. We orient with our own filters, as does our enemy; we need to identify those filters. By knowing them, we can corrupt them, which is the goal of moral warfare. In assessing our adversary’s orientation, we learn his style of war. We must also realize that we need more than one orientation. To avoid predictability to our enemies and ensure adaptability to future threats, we require a “repertoire of orientation patterns,” and people with a wide variety of backgrounds and experience so that we have even more filters available for application.46

Finally, to fully exploit orientation in future warfare, we need another filter in the mix: the grand ideal/strategic narrative outlined above. In moral warfare, that is the filter which guides, however subtly, each action across every level of war. It is a constant in the analysis and synthesis that transitions orientation to decision. This turns orientation into the “supra-orientation” that Boyd believed was the foundation for success in moral warfare (see Figure 4).47

Chapter 4 – The Conduct of War

Let me caveat that I do not propose discarding maneuver warfare. It remains a valuable operational construct for our conventional forces. But moral warfare subsumes maneuver warfare in itself while layering on additional concepts. These concepts seek to employ unorthodox (or Sun Tzu’s ch’i) forces and use conventional forces in unorthodox ways.48

Two examples from today’s preeminent practitioner of moral warfare highlight its possibilities:

[Russia] paralyzes the target state’s functions by all means necessary to implement “deep penetration.” In this regard, the Ukrainian intelligence apparatus, and probably high political echelons too, was so systematically penetrated by several Russian intelligence agencies … that although the Ukrainian General Staff warned Kiev about “unusual Russian activity in Crimea” in January 2014, this was completely ignored.49

The campaign’s success can be measured by the fact that in just three weeks, and without a shot being fired, the morale of the Ukrainian military was broken and all of their 190 bases had surrendered. Instead of relying on a mass deployment of tanks and artillery, the Crimean campaign deployed less than 10,000 assault troops—mostly naval infantry, already stationed in Crimea, backed by a few battalions of airborne troops and Spetsnaz commandos—against 16,000 Ukrainian military personnel. In addition, the heaviest vehicle used was the wheeled BTR-80 armored personnel carrier.50

The remarkable thing about the second example is the parallel between the Russian units employed and the Marine Corps’ current force structure. To wit: we are already positioned to do this. We just need a few more ch’i elements—most of which currently exist in some form—to fulfill moral warfare’s promise.

Boyd outlined the factors and aims that a nation using moral warfare would direct at its adversary.51 He did not otherwise provide a theoretical construct for its execution; fortunately, one may be found in a highly-developed Russian theory, which the Kremlin is increasingly adept at exercising. This is the concept of “reflexive control,” which combines orientation and deception into a ruthless form of moral warfare.

Reflexive control mirrors maneuver warfare in that it interferes with the enemy’s decision-making process. It is a means of conveying to … an opponent specially prepared information to incline him to voluntarily make the predetermined decision desired by the initiator of the action.52

It targets both human/mental and computer-based decision-making processors. A brief summary shows how it brings orientation and deception into play:

‘Reflexive control’ occurs when the controlling organ conveys (to the objective system) motives and reasons that cause it to reach the desired decision … the nature of which is maintained in strict secrecy. The decision itself is made independently. A ‘reflex’ itself involves the specific process of imitating the enemy’s reasoning or imitating the enemy’s possible behavior and causes him to make a decision unfavorable to himself.

In fact, the enemy comes up with a decision based on the idea of the situation which he has formed, to include the disposition of our troops and installations and the command element’s intentions known to him. Such an idea is shaped above all by intelligence and other factors, which rest on a stable set of concepts, knowledge, ideas and, finally, experience. This set usually is called the ‘filter,’ which helps a commander separate necessary from useless information, true data from false and so on. [emphasis added]

The chief task of reflexive control is to locate the weak link of the filter and exploit it.53

Described here is a theory directed expressly against the enemy’s orientation, complete with a similar characterization of the filters from Boyd’s model. Reflexive control clogs, corrupts, and corrodes the information going into those filters to manipulate the enemy on the moral plane. It depends on levels of deception so profound that every input to an adversary’s OODA loop is distorted, closing the loop to everything but that which we choose to feed into it. It implements the destructive and constructive sides of Boyd’s moral warfare by attacking enemy linkages and isolating his components (destructive) and feeding deception into his loop at all points to build a false picture (creative), thus driving what limited actions the enemy takes toward our own ends. We may even want to keep some or all of the enemy’s linkages intact to better corrupt them, to feed into his confusion and uncertainty, and keep his loop closed (see Figure 5).

Such control demands a truly perceptive and comprehensive understanding of the enemy’s orientation, to “see” through his filters as he would.54 We must know the thought processes of his soldiers and politicians, from privates through top commanders; we must

… be aware of his military doctrine, how leaders are taught to use the services and branches, historical precedents, the nation’s principles for using men and equipment during operations.55

As I stated, this does not replace maneuver warfare. We should still strive to operate at a faster relative tempo than our enemy, keeping our decision-making process intact and dynamic while disrupting his own. But in applying our supra-orientation to the enemy, we may discover that “[seeking] to shatter” his cohesion, or making him realize that he “cannot cope” with the situation,56 are not ideal goals. Maybe the enemy does not need to be shattered or paralyzed in toto. By using deception and the ten thousand combinations of warfare beyond limits, we can inject menace, uncertainty, and mistrust into his decision-making system across all levels of war and allow his feedback loops to magnify their effects over time.57 If, by so doing, we can degrade his system’s cohesion and adaptability—and keep it degraded—the end result may suit us equally well as shattering him, with fewer resources expended.

Conversely, some adversaries never admit that they “cannot cope;” the Japanese forces of World War II and hardcore Islamists today come to mind. An enemy maneuvered into not coping may also suddenly decide that he can cope again:

… to call an enemy defeated because he has accepted the likelihood of actual physical defeat while his forces are largely intact may prove short-lived if he changes his mind.58

By poisoning the enemy’s orientation so that he cannot respond effectively, and by corroding his cohesion and adaptability, I really don’t care whether he refuses to despair or despairs and then changes his mind. Finally, perhaps we want to let the enemy think he is coping: by clouding and corrupting his inputs, the enemy will simply be coping with a situation detached from reality. By so closing his loop, he may truly believe he is coping until the bitter end.

In doing these negative things to the enemy, let’s not forget the positive aspect of moral warfare that works simultaneously to bolster our moral advantage. As we feed our adversaries friction, fog, and fear, the grand ideal inculcates in our troops and countrymen moral supremacy, motivates our allies, and further undercuts our adversary by its contrast. We adapt this ideal to each level of war as it travels down from the national leadership to the strategic corporal, adjusting it when necessary as its results travel back upward. We tell our story loudly through every venue, and across all levels of war; our enemy’s narrative cannot get out, and is incoherent and unhinged from reality if it does.

Conclusion

The above may imply that the Marine Corps must undertake significant restructuring to employ this type of warfare. This is not so, as our MAGTF is already scalable up or down and contains the cheng (“orthodox”) force embedded within. We stand a mobile, rapid response force well-versed in maneuver warfare tempo and exploiting decision loops; we have the foundation upon which to build a ch’i structure. This structure requires more robust cyber, information, and propaganda arms to cloud and corrupt the enemy’s orientation. We have great capabilities for this in our agencies at home; we need the authority to borrow them, make them expeditionary, and employ them without extra interference from above the MAGTF commander. And we have a compelling argument—duty, even—to request such resources and authority be given the MAGTF. We are America’s first responders, and in a flattened world where the levels of war are virtually coexistent, that first responder may be the only chance for a decisive response.

We must also look at how we can use our orthodox forces in unorthodox ways, “beyond limits.” Imagine a MAGTF whose forcible entry did not risk expensive stealth aircraft in negotiating an integrated air defense system or expose ships to antiaccess/area denial missile systems, but instead could shut down a power grid; spoof local social media accounts; jam satellites; snarl ground and air traffic patterns; ignite forest fires to tie up military assets; reprogram valve sequences for oil, natural gas, and water pipelines to disrupt distribution; delete or alter military equipment maintenance records; or crash financial networks before inserting “little green men” of its own to sow further confusion and mayhem. Pushing this forward to the MAGTF vice sheltering it in the continental United States is critical should an adversary attempt—which they will—to cut or degrade our own global connectivity. Putting ch’i assets with the MAGTF lets us bring moral warfare to the enemy regardless of how he affects our other global linkages.

But before we can do this, we must be willing to look hard at our basic philosophy of conflict. As I said at the outset, such an assessment is necessary if, as an institution, we mean to walk the walk on innovation. Per Gen Krulak, we cannot allow ourselves to stagnate; thus, in adjusting our Corps to the world in which we live, not even Warfighting is sacrosanct. Today’s world, with its flattened levels of war, interconnectivity, and information saturation, is primed for moral warfare. We must understand it and be ready to operate within it.

Notes

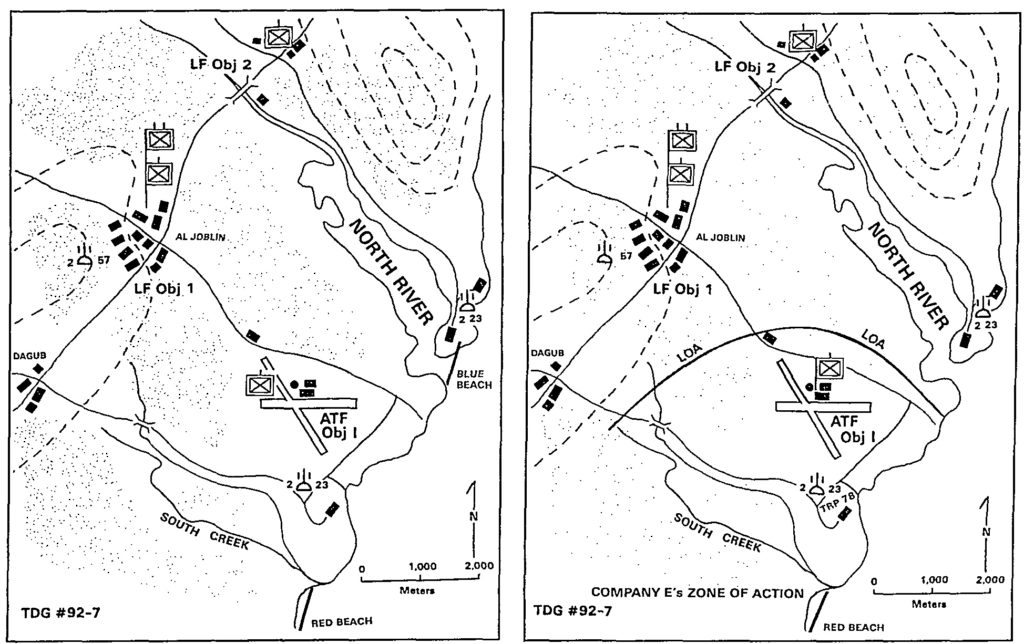

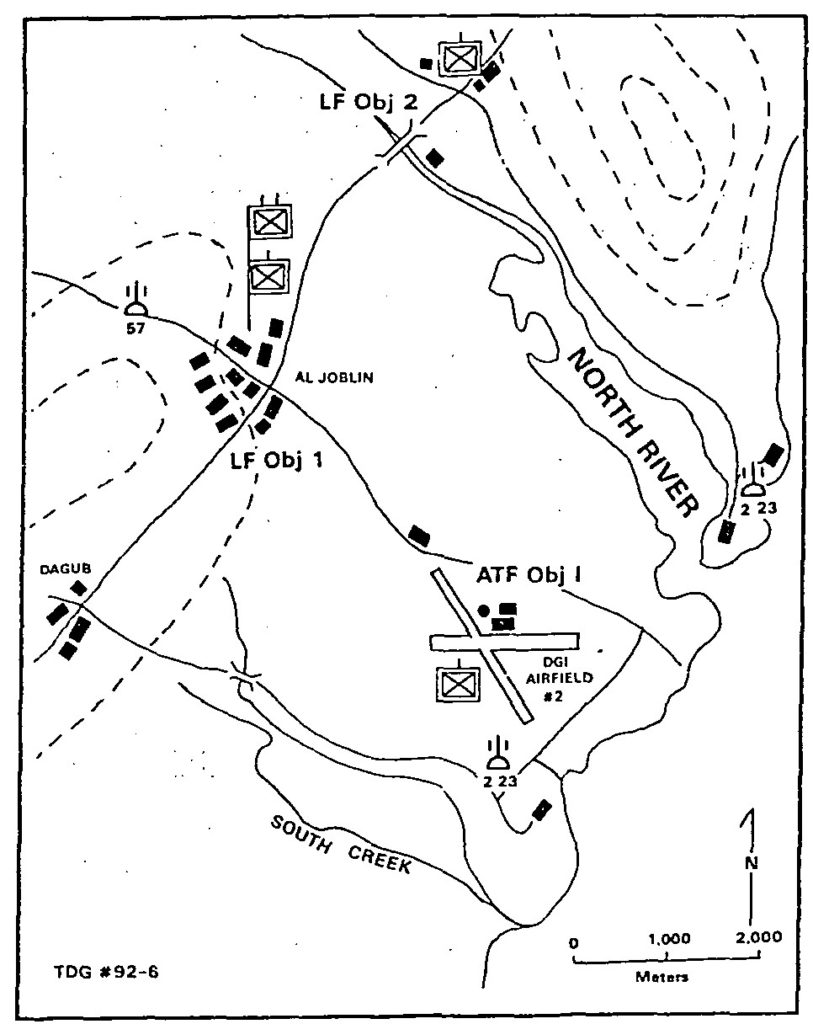

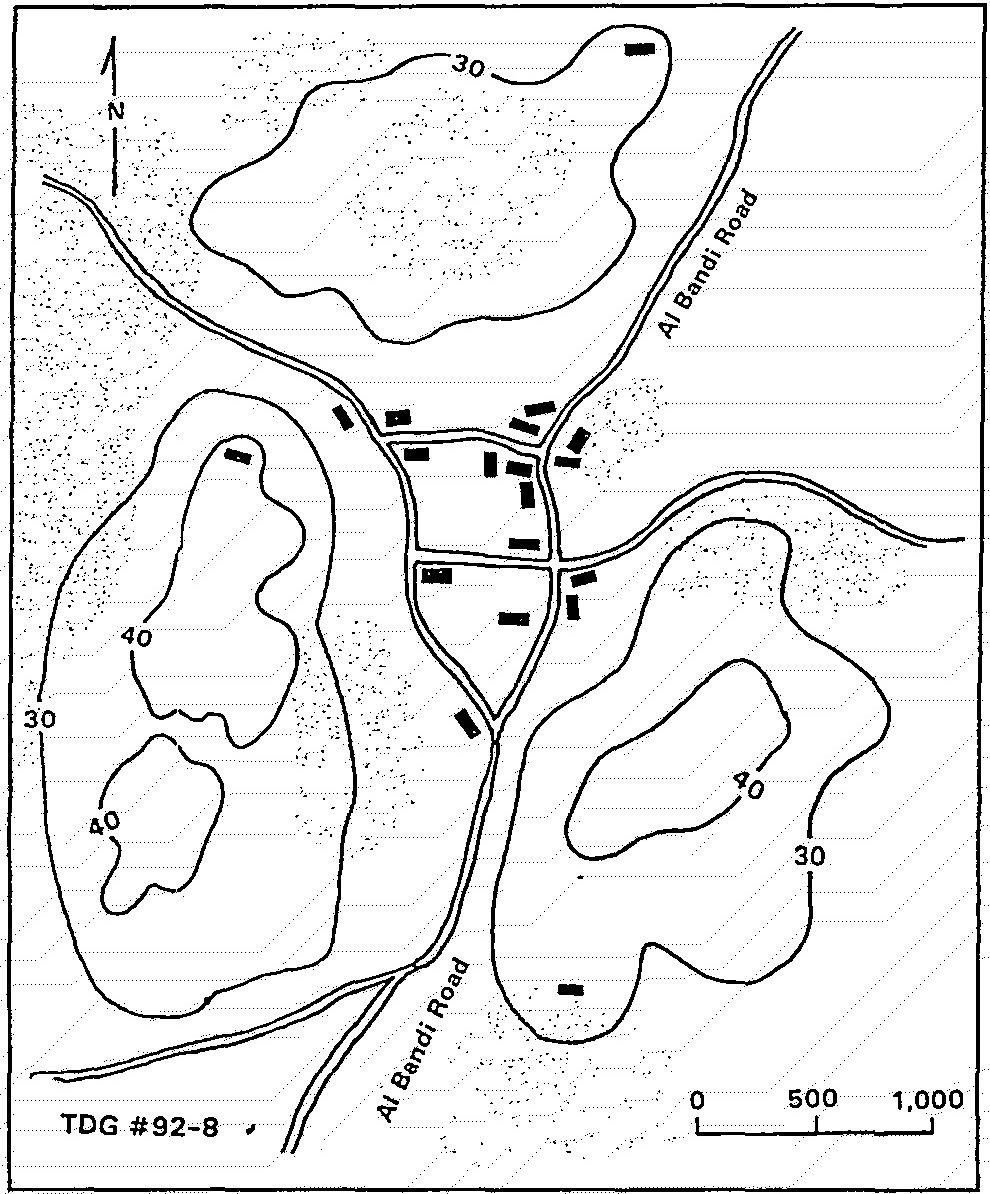

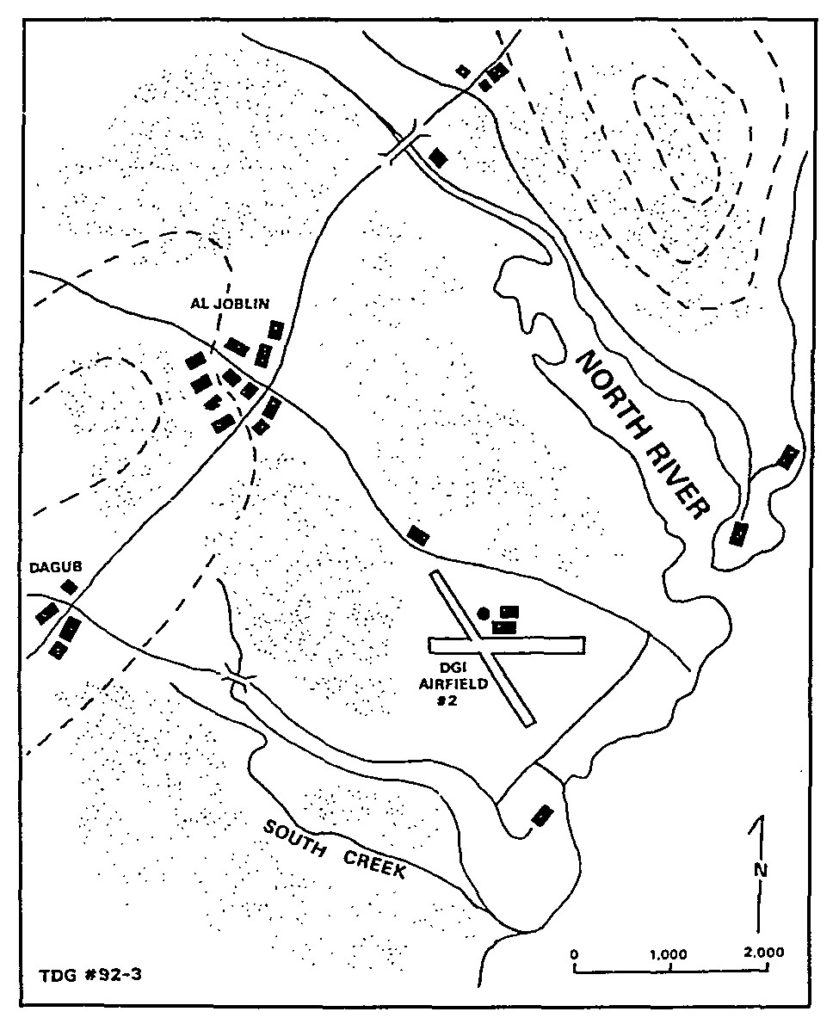

The CO, 26th MEU was ordered to assault and secure Dull Garrison Island Airfield #2 so it can be used by follow-on forces arriving from the United States. The airfield is only being defended by one of the enemy’s small battalions (400 men). The battalion headquarters and one rifle company appear to be located in the village of Al Joblin. The airfield itself (ATF Obj 1) is being defended by a second rifle company. The enemy’s third rifle company is located near the bridge spanning the North River, which is virtually dry at this time of the year. Three antiaircraft positions have been identified and are depicted on the accompanying map.

The CO, 26th MEU was ordered to assault and secure Dull Garrison Island Airfield #2 so it can be used by follow-on forces arriving from the United States. The airfield is only being defended by one of the enemy’s small battalions (400 men). The battalion headquarters and one rifle company appear to be located in the village of Al Joblin. The airfield itself (ATF Obj 1) is being defended by a second rifle company. The enemy’s third rifle company is located near the bridge spanning the North River, which is virtually dry at this time of the year. Three antiaircraft positions have been identified and are depicted on the accompanying map.

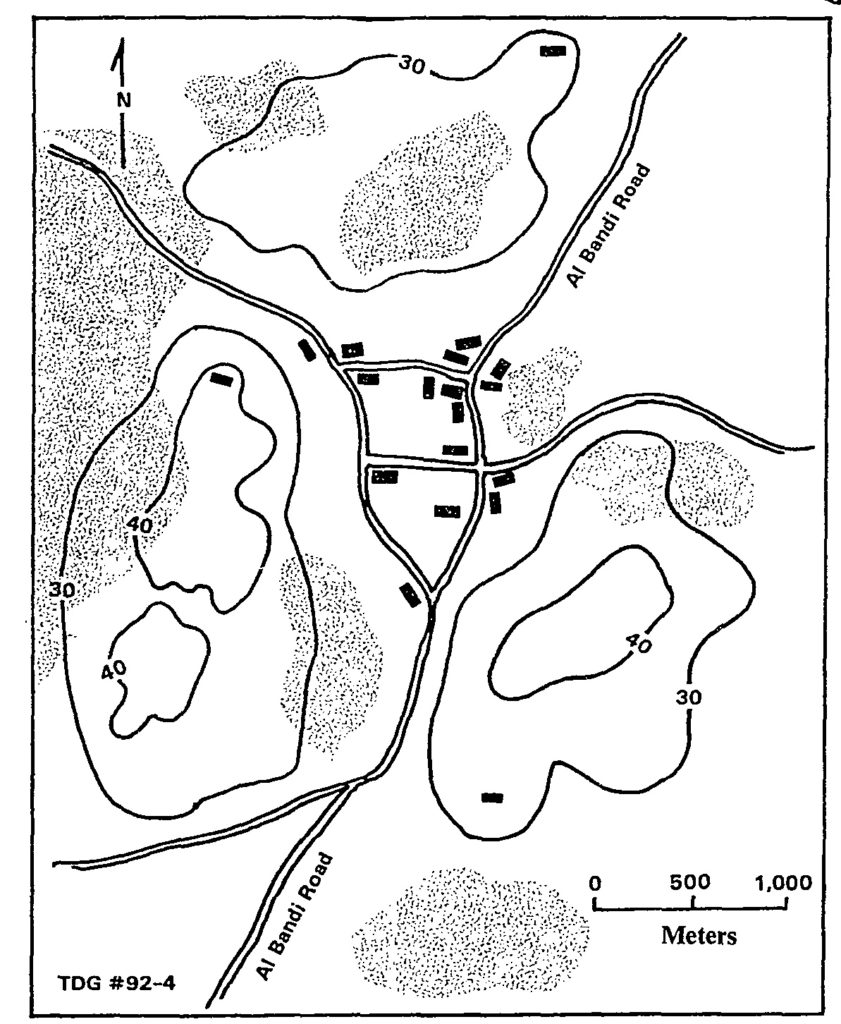

As the commanding officer BLT 2/8 (part of 26th MEU), you and your command are feeling pretty good about yourselves after Company G was able to rescue the American Ambassador. The general situation, however, has deteriorated further. The forces of BAD invaded Dull Island and are threatening to overrun the Marine garrison, which has suffered heavy casualties and is now fighting for survival on the outskirts of Al Habib. Furthermore, it would appear that BAD is already reinforcing and fortifying its defense of Dull Garrison Island even while it is attempting to eliminate the Marine stronghold.

As the commanding officer BLT 2/8 (part of 26th MEU), you and your command are feeling pretty good about yourselves after Company G was able to rescue the American Ambassador. The general situation, however, has deteriorated further. The forces of BAD invaded Dull Island and are threatening to overrun the Marine garrison, which has suffered heavy casualties and is now fighting for survival on the outskirts of Al Habib. Furthermore, it would appear that BAD is already reinforcing and fortifying its defense of Dull Garrison Island even while it is attempting to eliminate the Marine stronghold.

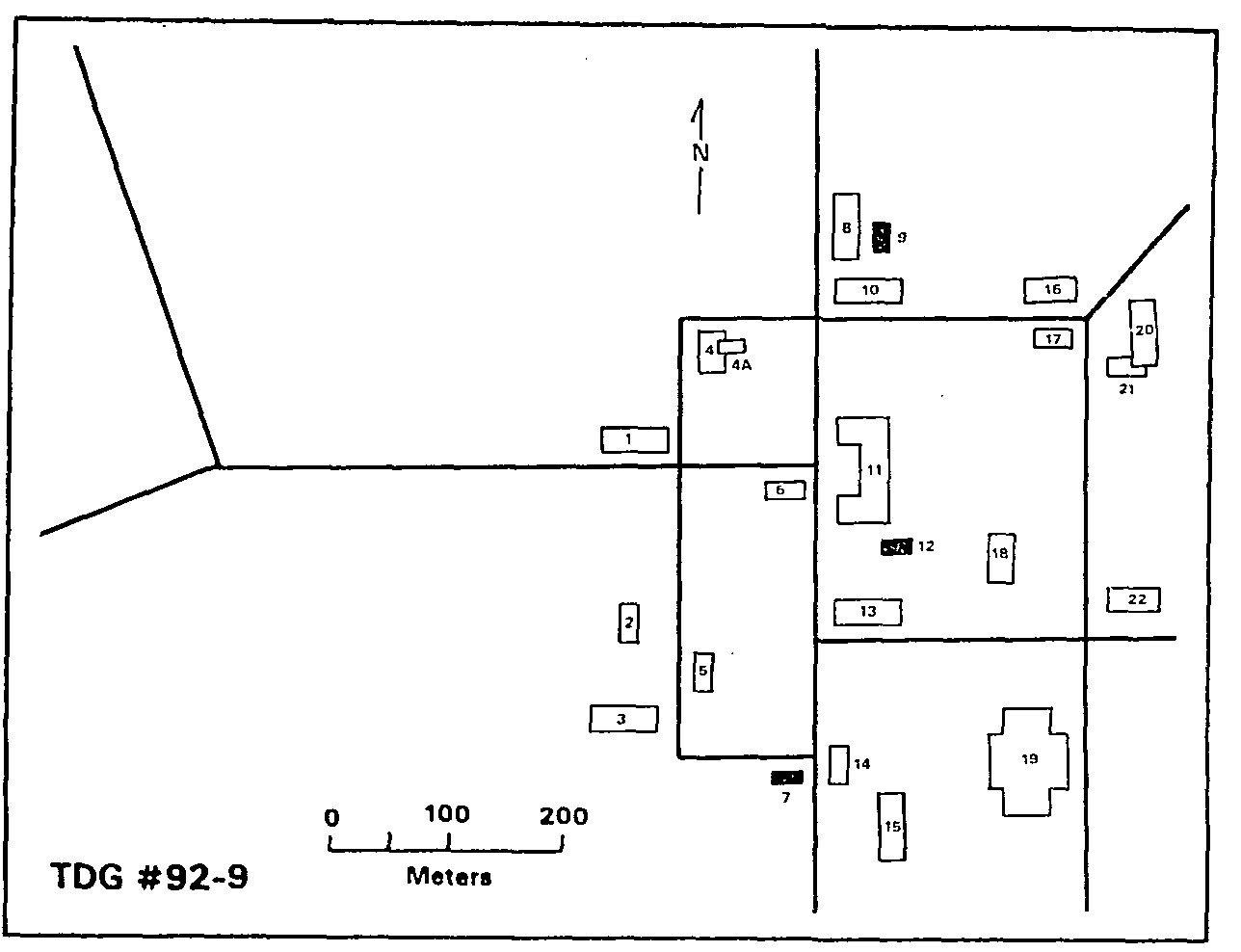

This is a continuation of TDG 08-16R. The enemy is continuing to press its assault of Dull Garrison Island. Against overwhelming odds and in the face of heavy casualties, the fight is not going well for our provisional battalion, which has begun to consolidate its survivors into a single perimeter here at Al Habib—a relatively large town and the regional communications and transportation center for this part of the island. The enemy’s main body is still many kilometers to the north but getting closer. Eventually, the enemy’s main attack is expected to come from that direction.

This is a continuation of TDG 08-16R. The enemy is continuing to press its assault of Dull Garrison Island. Against overwhelming odds and in the face of heavy casualties, the fight is not going well for our provisional battalion, which has begun to consolidate its survivors into a single perimeter here at Al Habib—a relatively large town and the regional communications and transportation center for this part of the island. The enemy’s main body is still many kilometers to the north but getting closer. Eventually, the enemy’s main attack is expected to come from that direction.

Situation

Situation

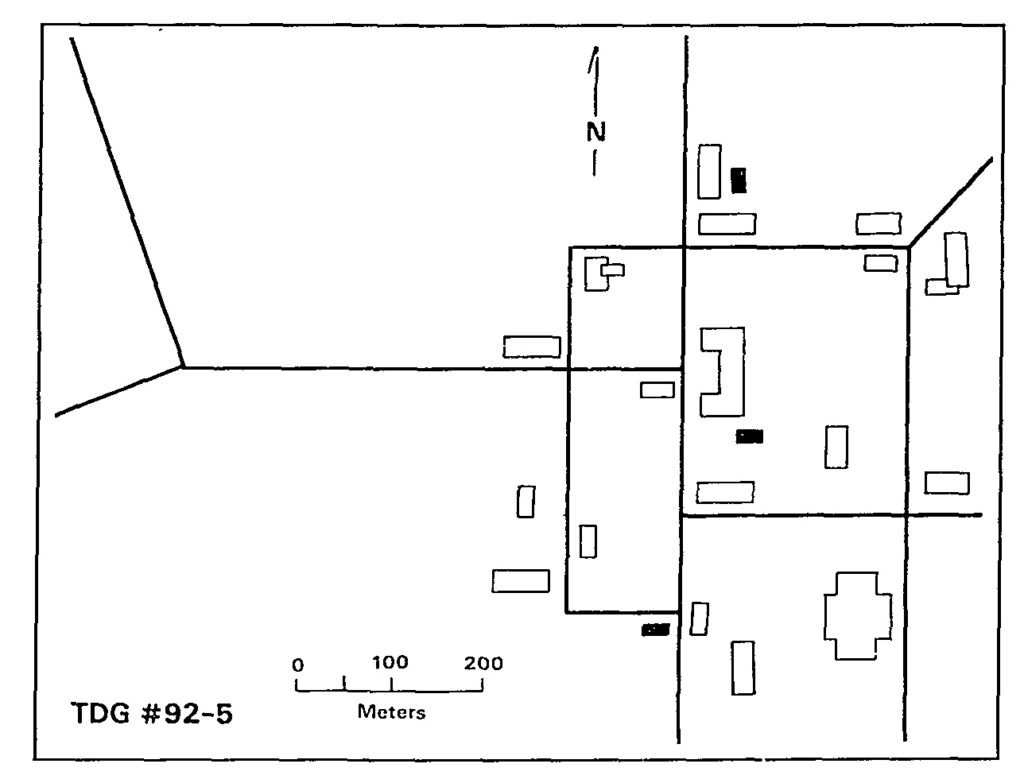

Beginning with the fall of communism in the early 1990s, the past several years have witnessed tremendous changes throughout the world. You find yourself the commanding officer of the 1st Special Infantry Company in a provisional rifle battalion that has been formed recently and deployed (without major attachments) on a deployment for training to Dull Garrison Island in the northern region of the Indian Ocean. In part, the deployment maintains presence and replaces the more expensive regular deployment of amphibious forces. It also provides familiarization and training for potential leaders of the local defense force forming on the island.

Beginning with the fall of communism in the early 1990s, the past several years have witnessed tremendous changes throughout the world. You find yourself the commanding officer of the 1st Special Infantry Company in a provisional rifle battalion that has been formed recently and deployed (without major attachments) on a deployment for training to Dull Garrison Island in the northern region of the Indian Ocean. In part, the deployment maintains presence and replaces the more expensive regular deployment of amphibious forces. It also provides familiarization and training for potential leaders of the local defense force forming on the island.