By The Ellis Group

Nineteen years after the release of MCDP 1, Warfighting, the Marine Corps finds itself in an environment of increasing strategic uncertainty and rapid introduction of new technology. While many new capabilities and concepts are unfamiliar, the situation is not. One hundred years ago, new technologies like the airplane, radio transmission, automatic weapons, and the tank were being introduced on battlefields all over the world. Every major combatant attempted to integrate the new weapons but few successfully sustained those efforts after the war.

Thus, World War I was an example of a conflict where new technologies were being introduced to military organizations that employed outdated tactics. It produced a situation where none could win; nations could only be ground to dust by continued resource depletion and attrition—first Russia, then the Ottoman Empire, and finally Germany. In the aftermath, tactics continued to stagnate as the war was viewed as an aberration. Although every nation changed their doctrine, few managed to bring all the new capabilities together.

There were two exceptions: Germany and the United States Marine Corps. LtCol Pete Ellis, in his Naval War College papers and lectures as well as Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia, proposed new tactical combinations and new, combined arms units purpose-designed to carry them out. His concepts were an embryonic version of the modern MAGTF, and Gen John A. Lejeune reformed the Marine Corps along those lines. The Germans studied and experimented, eventually developing a suite of tactics and newly designed units that would eventually come to be known as blitzkrieg.

In both cases, no new capabilities were developed. Tanks, aircraft, landing craft, and radios were all introduced, but not effectively integrated, during World War I or before. Specialized landing craft, for example, were proposed as early as 1798 and were used in North Carolina during the Civil War. The Germans and the Marine Corps succeeded in combining existing technologies and ideas in unique and innovative ways to produce something larger than the sum of the parts. Battlefield success throughout history is not necessarily achieved by military organizations that invented new technology but rather by those that best integrated them into a cohesive whole.

Today, the situation is similar. There are frequent calls to get back to the peer-on-peer methods of the 1990s. This is a coded proposal to stagnate and ignore the changing character of warfare. Last time it happened, thousands died for the mistake.

Achieving a cohesive whole does not just require the acquisition of emerging and maturing capabilities, but also necessitates the development of concepts and doctrine that guides use and coordination as well as the training and education methods that support the concepts. As a reflection of the Marine Corps maneuver warfare philosophy, MCDP 1, Warfighting achieved this cohesion for the Marine Corps of the late 20th century. The document provided guidance on how to organize, train, equip, and fight the organization in order to integrate each part into a whole greater than the sum of its parts.

MCDP 1, Warfighting can ensure that the Marine Corps achieves another such evolution for the 21st century. The concepts that underpin the document are timeless and their application on the modern battlefield just as effective as ever. As we shall see, even our adversaries apply maneuver warfare. MCDP 1, then, provides the best guidance as to how the Marine Corps should evolve for the future. But is the Marine Corps still institutionally able to execute maneuver warfare?

There is a concept in organizational theory called strategic fit. The concept is essentially an expression of whether or not an organization is well adapted to its environment. As an organization, it behooves the Marine Corps to assess whether it is strategically fit for its environment, in this case the prosecution of maneuver warfare in the 21st century. The question is whether the Marine Corps as an organization is structured, trained, equipped, and educated to execute maneuver warfare effectively in the modern context.

First, this article will examine trends in the current strategic environment for insight into both changes and continuities. Next, it will examine MCDP 1, Warfighting against the backdrop of the strategic environment. Third, it will describe instances of maneuver warfare during current operations. Lastly, it will lay out how the Marine Corps will need to apply the philosophy in the future and draw specific conclusions about how MCDP 1, Warfighting should be applied to the strategic environment.

The Strategic Environment

The last revision of Warfighting was signed by Gen Charles C. Krulak in 1997, eight years after it appeared as FMFM 1, Warfighting. In Gen Alfred M. Gray’s preface to the updated edition, he stated that,

Like war itself, our approach to war fighting must evolve. If we cease to refine, expand, and improve our profession, we risk becoming outdated, stagnant, and defeated.1

The 19 years since have seen dramatic changes in warfare. The Marine Corps has participated in two major wars on land and countless other operations around the globe, all while maintaining a presence on the seas. Myriad new weapons, technology, and capabilities have been taken aboard and integrated with legacy systems, including the MV-22 Osprey, the HIMARS, and various unmanned aircraft systems (UASs). Operations have run the gamut of the spectrum of conflict, from training and advising missions in Africa to the Second Battle of Fallujah. While few would doubt that MCDP 1’s embrace of maneuver warfare allowed the Marine Corps to better keep pace with such rapid change, the pace of change remains remarkable.

Looking ahead, this pace of change and the corresponding need for adaptation shows no signs of decreasing. More than likely, it will increase. The recently released Joint Staff study of global trends, Joint Operating Environment 2035, has identified a strategic environment characterized by the same fracturing state authority, ideological violence, weapons proliferation, and complexity that Marines are now used to operating in. These trends presage future battlefields inhabited both by humans and robots, professionals and amateurs, and state and non-state actors, no matter the conventional or irregular nature of the conflict.

Most notably for the Marine Corps, the study predicts, “Increased competition across the air and maritime domains,”2 a trend that is already obvious in the South China Sea and as Russia takes violent action to ensure its access to the Black Sea in Ukraine and the Mediterranean Sea in Syria. In terms of technology, autonomous robot systems and radio-frequency weapons will be more common and adversaries will be able to easily achieve C3/ISR (command, control, and communications/intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) capabilities commensurate with our own whether they are state or non-state actors.3 Lastly, the importance of information operations will skyrocket. The report states that:

Adversary information operations will focus on evolving their messages, goals, aspirations, and objectives and adapting their narrative strategies to affect a variety of friendly, neutral, and hostile audiences. Information warfare and propaganda efforts will be reinforced by military activities and violent action … 4

This level of integration of information warfare with other military means is something the Marine Corps has yet to achieve.

Information warfare can no longer be ignored as all future warfare will take place within a globalized digital media environment (GDME). Some adversaries have already mastered the use of information. Col T.X. Hammes, USMC(Ret), describes a “modern insurgency” as “ … essentially a strategic communications campaign supported by military action rather than a military campaign supported by effective strategic communications.”5 Marines are used to operating in a mode where maneuver is the main effort, for friendly and enemy forces. Increasingly, the main effort will be other means and will shift between means rapidly.

Lastly, technology is advancing rapidly, thus bringing new capabilities to bear on the battlefield. The Marine Corps Warfighting Lab has been at the forefront of many of these capabilities. Some of the most important of these are information, cyber, and electronic (ICE) warfare. As mentioned above, information warfare is of vital importance because of the Information Age environment in which the Marine Corps will operate. It can no longer be an annex to the operations plan or a task relegated to the collateral duties of a staff officer at high levels of command; it must be taken into account any time Marines plan any kind of operation. As military units, local populations, infrastructure, and weapons systems become increasingly digitally interconnected, cyber warfare offers great threats and great opportunities. Electronic warfare has been a U.S. asset for years, but sophisticated systems that can disrupt, deceive, and destroy vital electronic systems are proliferating to many of our adversaries. It is not just important to integrate these capabilities into our offensive operations, but defensive measures must continually be taken to reduce the electromagnetic signature of all Marine Corps units and to mitigate the effects of enemy electronic warfare.

The Maneuver Warfare Philosophy

For all of these changes, maneuver warfare as the Marine Corps’ institutional philosophy not only remains sound but also continues to offer insights. MCDP 1 was written to remain timeless and has succeeded in doing so. The fact that the first citation is Carl von Clausewitz’s On War (184 years old) and the second is Sun Tzu’s The Art of War (roughly 2,500 years old) is no accident.

It is Clausewitz that informs much of the first section, “The Nature of War.” The Prussian’s famous treatise was not written as a work that explains how to win wars but rather what war is as a sociological phenomenon. MCDP 1 defines war in a few ways, all based on Clausewitz’s definitions and all still relevant today. War remains an act of politics with the addition of violent means. Even ideological and religiously motivated non-state actors, at their core, have policy goals: the political power to enact their ideology. In defining war, it is important to remember the two aspects of war: its nature and its character. Its nature never changes. Its character, how it is expressed in the real world, is never the same.

In addition to its nature, MCDP 1 describes numerous characteristics of war: friction, fluidity, complexity, and its human character. No matter the technological means employed, war remains a human act, and its dualistic nature causes friction, fluidity, and complexity. Despite claims to the contrary, we continue to struggle friction and the uncertainty in war. Every tactical act is beholden to the play of probability and can never be certain.

Lastly, MCDP 1 lays out three elements of war: the physical, the mental, and the moral. Maneuver warfare does not stop at inflicting physical stress on the enemy but also takes into account the mental effects that our tactics have on the enemy. An artillery barrage does not just kill and wound, but also shocks and overpowers the human mind. No matter what physical and mental forces assail the enemy, his morale and the moral cohesion of his unit will keep him in the fight unless it is shattered. Conversely, it is the esprit de corps and cohesion of Marine Corps units that makes them potent no matter the physical and mental adversity. Thus, the moral cohesion of the enemy is the true target of tactics. As MCDP 1 says, “The combination of the physical, mental, and moral effects we inflict on the enemy is combat power.”6

The second section, “The Theory of War,” is the philosophy’s view on how wars are fought, reiterating that it is an act of and subject to policy. The point of this repetition is to remind Marines that their actions serve a larger purpose for the Nation: “The policy aims that are the motive for any group in war should also be the foremost determinants of its conduct.”7 This is why rules of engagement are so vital: they ensure that the tactical conduct of a war contributes to its policy aim. This is a lesson that Marines had to viscerally relearn in recent years.

There is no reason for the Marine Corps to stop dividing war into tactical, operational, and strategic levels, but the separation is not nearly as important as the convergence thereof. The character of modern warfare is a clear convergence in the levels of war: tactical actions can have instant and global strategic effects in a global digital media environment. As Marines fight the Nation’s battles, they must do so with the realization that every tactical decision—or indecision— has a positive or negative strategic effect. It either contributes to or detracts from achieving the strategic aim. This dynamic has been less obvious in the past, but on the modern battlefield, even a private’s actions can have immediate and profound strategic effects. This does not mean that we must treat every Marine as a strategist, but Marine leaders do need a basic understanding of strategy in order to make effective tactical decisions.

This section discusses the interplay of the offense and the defense as well as initiative and response. MCDP 1 connects the initiative most often with the offense, but we should remember this is not always so. If one can divine the enemy’s offensive plan and decide where to defend against it or, better yet, induce the enemy to attack you where you planned a devastating defense, you have both the initiative and the strength of the defense. MCDP 1 one states exactly this,8 but the idea has seemingly disappeared from discussion. Another dichotomy discussed in this section is attrition versus maneuver warfare. Attrition warfare was meant as a theoretical demonstration of how warfare would be conducted if one were to adhere to the extreme opposite of every tenant of maneuver warfare.9 This was done to illustrate the concept of maneuver warfare. It had the effect of turning attrition into a dirty word. This is a false conception. The overly-centralized, procedural methods described should be avoided, but the destruction of enemy forces—accomplished along maneuver warfare lines—is an integral part of Marine Corps operations.

The last part of this section gets down into the tactics that typify maneuver warfare, starting with maneuver (juxtaposed with mass) and including surprise and boldness. MCDP 1 briefly defines maneuver as, “ … circumvent a problem and attack it from a position of advantage rather than meet it straight on.”10 The most common depiction of using maneuver to gain advantage is positional: striking a flank, seam, or rear area in the enemy system. While speed, firepower, mass, and surprise all contribute to maneuver, there are various other ways to out maneuver an enemy system, including cognitively.

The cognitive level is an important part of maneuver warfare because, as MCDP 1 says when discussing surprise, “Surprise is not what we do, it is the enemy’s reaction to what we do.”11 This is key because, as maneuverists, we do not just take into account what physical destruction our actions cause but also the mental effect our actions have on the enemy’s mind. Surprise is one these effects.

Section three, “Preparing for War,” is an application of the philosophy to the Marine Corps in terms of organization: it covers everything from training, personnel policy, leadership, and acquisitions. The first major point is that the Marine Corps should operate as MAGTFs. It lays out how we should view our own doctrine, the Marine Corps’ conception of professionalism, and how we can become an organization designed for maneuver warfare. Many of these ideas were ahead of their time in terms of organizational theory and mechanics.

As solid as this section is, it is the most depressing part of MCDP 1 to read—nearly every paragraph makes a recommendation that the Marine Corps has failed to achieve. The habitual relationships that are supposed to be the foundation of every MAGTF have all but disappeared.12 Our philosophy is that doctrine should not be viewed as prescriptive, but our premier exercise, the integrated training exercise, ignores the recommendation for free play and even features officers assigned to no other duties but mandating doctrine and punishing transgressions. This is in direct violation of MCDP 1.13 Professionalism for officers is defined first as “a solid foundation in military theory and knowledge of military history,”14 but neither of these is truly evaluated by promotion boards. As long as the PME box is checked, it is assumed. The study of war is recommended not once but throughout the book and in every chapter. Physical fitness is mentioned only once, and that is just to say that the study of war “ … is at least equal in importance to maintaining physical condition and should receive at least equal time.” Yet, a Marine could go his entire career without cracking a book on war, so long as he can do pull-ups.

Section three goes on to say that commanders are expected to provide adequate time for subordinate unit training at each echelon,15 but more training is now mandated than there are training days in a year.16 Our personnel management system is supposed to

… recognize that all Marines of a given grade and occupational specialty are not interchangeable and should assign people to billets based on specific ability and temperament.17

It still does not. The chapter is essentially a roadmap for how to apply our maneuver warfare philosophy to the Supporting Establishment of the Marine Corps. Unfortunately, this is a road the institution has yet to take.

The last section, “The Conduct of War,” is a series of specific conclusions for the Marine Corps based on the philosophy of war laid out in the first two sections and assuming that the recommendations of the third section have been implemented and a maneuver warfare organization achieved. The first major conclusion is our method of C2: mission tactics. There is little to say about the relevance of this concept as the U.S. Army has recently adopted it. But a decentralized method of C2 sacrifices unity for speed of action and reaction. To regain some of that unity, the next three concepts are key: commander’s intent, main effort, and surfaces and gaps. Marine leaders of any rank can be trusted to accomplish their mission as they see fit if they understand the goal of their commander (commander’s intent), know which unit is tasked with the most important part of the plan so it can be supported (main effort), and know that advantage can be achieved by apply our strength against an enemy’s weaknesses rather than his strength (surfaces and gaps).

The above concepts are how we operate, but we apply combat power against the enemy on the physical, mental, and moral planes through combined arms. Combined arms depends on the availability and use of multiple, complementary weapons systems and effects applied in a coordinated manner. It is defined in MCDP 1 as “ … the full integration of arms in such a way that to counteract one, the enemy must become more vulnerable to another.”18 The ultimate aim of combined arms is to inflict this dilemma on the enemy. It is usually explained in terms of the simultaneous employment of direct and indirect fire weapon systems but any arm, including information, cyber, and electronic warfare, can be used in such a coordinated fashion.

Current Operations

This admittedly cursory review of the major maneuver warfare precepts as defined by MCDP 1 lays out how the Marine Corps is supposed to fight, but is that ideal suitable for the current and future strategic environment? To answer that question, there is no better way than to examine actual and potential adversaries as they have the most incentive to master such methods before we can. Such a review reveals that not only is maneuver warfare relevant, it is being actively employed all over the world.

Although often associated with conventional operations, the fighters of the Islamic State (also known as ISIS and ISIL) have proven that maneuver warfare concepts do not just apply to professionals. The terrorist group executed a lightning campaign against Iraq, capturing huge swaths of the country, looting advanced weaponry, and shattering the cohesion of the Iraqi Army in the same way that maneuver warfare aims to do. First, the group established a base area in Eastern Syria by co-opting or eliminating rival anti-Syrian government groups already located there. They did this with a clever information warfare campaign, establishing communications with each group, and telling them that ISIS would only attack the other groups. They further camouflaged themselves by dropping their trademark black uniforms and wearing brown civilian clothing like the rebels. When ISIS eventually attacked all of the rebels, every rebel unit expected to be left alone and was completely unprepared.19

The Islamic State did not stop there. After pushing into Iraq, ISIS fighters waged a shaping campaign against the Iraqi Seventh Division around Mosul prior to taking the city. For almost a year prior to actually assaulting Mosul, ISIS identified effective and loyal Iraqi Army officers and assassinated them, on and off duty by various methods.20 This caused a pervasive sense of fear and instability in the division, undermining its moral cohesion. When the main attack finally did occur, the units melted away; their cohesion finally shattered.

Just such a far-sighted shaping campaign may already be ongoing by a vastly different strategic actor, the People’s Republic of China. In recent years, China has stepped up its efforts to bolster and enforce its claim over the South China Sea, bringing it into conflict with many of its neighbors such as Vietnam and the Philippines. Here, deception is the key method as China masked its construction of offshore oil rigs and artificial islands built to achieve de facto control over the area. The most notable deception effort is the repainting of maritime security ships as Chinese Coast Guard ships.21 This takes advantage of Western assumptions about the purpose of a Coast Guard (law enforcement and rescue except during times of war) to mask their true purpose: keeping foreign vessels from observing the artificial islands and oil rigs. While intelligence analysts may easily see through such methods, it allows China to extend its control over the region without triggering Western interference because the general public does not notice.

The most dangerous current application of maneuver warfare ideas may perhaps be Russia. The Armed Forces of the Russian Federation have gone through major modernization efforts since the collapse of the Soviet Union, but those efforts have accelerated under President Vladimir Putin, especially after the 2008 invasion of Georgia. Russia has streamlined every aspect of its army, including the elimination of all levels of the chain of command above the brigade and below the regional level. The truncated chain of command fosters rapid C2 as there is just one headquarters level between brigade commanders and the Russian General Staff.22 (There is some indication that Russia is reversing this decision, however.23) The professionalism of Russian soldiers has also increased as conscription continues to be phased out.

It is the structure of those brigades, however, that is key. Each one is a self-contained combined arms force. They are built around three battalions of motorized infantry, much like our MEB, but include much more firepower: two battalions of self-propelled howitzers, a rocket artillery battalion, an electronic warfare company, a tank battalion, an anti-tank battalion, and two air defense battalions, plus maintenance, communications, logistics, and engineering units.24 All of these capabilities are organic to the brigade rather than attached. Air support, however, is provided by the Russian Air Force and is attached prior to operations. These combined arms brigades have proven to be extremely potent in Eastern Ukraine, where the units work alongside Russian-sponsored insurgents. Fire support from the combined arms brigades is frequently directed via UAV feed—mostly commercial off-the-shelf systems—piped directly to the fire direction centers.

The trend in American operations for the past decade and a half has been increasing levels of command and increasing levels of coordination while simultaneously depending on technological overmatch as an advantage over adversaries. That technological overmatch is quickly eroding and studies have shown that a technological advantage is a poor determinant of success in warfare.25 Russia is reversing that trend, streamlining both decision making and increasing flexibility and responsiveness, especially in fire support. New technology is being integrated without using it as a crutch. Maneuver warfare, of course, encourages such methods and is built around being able to make and implement decisions faster than the enemy. While our philosophy supports this, our force structure does not. Russia has purposefully designed reforms that support exactly those tenants and can execute them in conventional and irregular operations.

Future Operations

While the above examples demonstrate that maneuver warfare remains relevant in the 21st century, they also show that the character of warfare has changed since MCDP 1 was released.

Perhaps the most important changes in the realm of fires. Traditionally, the Marine Corps has focused on a triad of field artillery plus close air support and naval surface fire support to provide the firepower necessary to conduct maneuver warfare. In recent years, however, both electronic warfare and cyber warfare have been developed by ourselves and by our adversaries. These capabilities are most relevant for Marines as they can perform fires-like missions.

Information warfare has always been a part of war, but thanks to the globalized digital media environment, it is now much more important and its effects both more potent and faster than in the past. Nowhere is this more obvious than when it comes to terrorist and insurgent organizations, but, as noted above, both Russia and China cloak operations and efforts in a screen of confusion generated by information warfare, not unlike a smokes screen created by artillery rounds but at a much higher level.

Yet, traditional firepower remains as potent as ever, if not more potent. Modern fire support systems have proliferated, too many non-state actors and peer adversaries retain large stocks of artillery and missiles, especially North Korea. World War I style trenches are currently in use by both sides around Mosul and in Eastern Ukraine. Kinetic, indirect fire is obviously still a threat, but that threat is made much more potent by the ubiquity of unmanned aerial ISR platforms. These systems can now be purchased off-the-shelf, and while they are not survivable in contested airspace, their expendability means that they will be used nearly everywhere for the foreseeable future. The trenches mentioned above are necessary because the ability to hide from forward observers is dwindling as more and more actors use UAVs to spot targets for fire support. Additionally, satellite technology also continues to advance and proliferate, reinforcing the ubiquity of ISR over every future battlefield.

Lastly, the United States does retain dominance on land, sea, and in the air when it comes to high-end combat. Both wars in Iraq proved that beyond a doubt. That dominance, however, merely means that adversaries are incentivized to fight in other ways. Just as we seek to always fight from a position of advantage so too will our enemies. This means that the use of asymmetric, hybrid, and unconventional approaches will only increase in the future. Even if a war against a peer adversary were to occur, the idea that tactics and warfare would simply revert to those of the 1940s when such conflicts were more common is ludicrous.

Therefore, in an effort to retain our strategic fitness as a warfighting organization, it behooves us to reinvigorate maneuver warfare for the current operating environment by reconceiving a few key concepts. Despite the many changes in technology, geopolitics, and warfare in the intervening years, the theoretical principles clearly remain sound. If anything, global trends toward agile, combined arms units and decentralized C2 means that maneuver warfare is more relevant than it was two decades ago. Still, a few refinements are necessary to ensure a better strategic fit.

21st Century Maneuver Warfare

These refinements are not changes to the documents but evolutions in how Marines think about and implement maneuver warfare. The core of maneuver warfare is a preference for maneuver: attacking from an advantageous position or angle. This remains effective, but the conception of maneuver must broaden even beyond the examples included in MCDP 1, Warfighting. Out-maneuvering our opponents will increasingly require us to divorce the concept of maneuver from maneuver units. Rather, maneuver is required across all MAGTF functions. It may require sustained electromagnetic or cyber fire support, an information warfare campaign, or ground operations against anti-air threats. This means the main effort will not always be a ground combat unit.

While maneuver is the core idea, the principle of mass is of increased importance despite its near absence from Warfighting itself. As the ISR and firepower capabilities of our opponents increase, so will our need to master the principle of mass. This does not mean that our forces should always be concentrated. Rather, the principle of mass has two components: concentration and dispersal. Military units disperse to move faster, avoid detection, mitigate the effects of fires, and take advantage of multiple avenues of approach. Forces then concentrate—either effects or units—to strike a strong blow against a decisive point or when necessary to secure key terrain. Some forms of maneuver require concentration, others require dispersal. Mastering the principle of mass means knowing when to concentrate and when to disperse and being able to function well in both modes.

Physical deployments of course matter, but maneuver warfare stresses not just the aspect of our physical tactics but the mental effects that those tactics cause. Marine leaders are well versed in the advantages and disadvantages of various maneuvers, but let’s take the next step and evaluate—from the enemy’s perspective—the expected mental consequences. MCDP 1 stresses surprise, and it is always good to surprise the enemy when possible, but there are other possibilities as well. First, deception is a potent force that is not necessarily linked with surprise. In the past, Marine forces have used deception to force enemies to commit forces to defend points that never get attacked and to obscure intended amphibious landings that do happen. Such methods will continue to be important, but any measures that deceive the enemy pollute his decision-making process and situational awareness. Even rapid, smaller attacks can overload an enemy C2 system and cause confusion. In the future, Marines will need to become better at not just overcoming friction but in introducing friction into the enemy’s system by contaminating his perception of reality. Cyber warfare especially offers many opportunities for this, but even properly planned kinetic fires can play a part.

The point of evaluating both physical and mental effects of our plans is to direct the battle in such a way that it shatters the moral cohesion of the opponent. MCDP 1 defines maneuver warfare as

… a warfighting philosophy that seeks to shatter the enemy’s cohesion through a variety of rapid, focused, and unexpected actions which create a turbulent and rapidly deteriorating situation with which the enemy cannot cope.26

But if the enemy’s cohesion is our target, what exactly is it?

The cohesion of a military unit is an aspect of what Warfighting calls the moral level of war. This should not be confused with the word morality. Military units, from fire team to army, are not just bound together as a whole by regulations and statutory authority. The shared values and loyalties of the individual members, tempered by shared training and adversity, along with organizational values and traditions, bind them together. This enhances everything from morale to courage and teamwork. Whether this is referred to as esprit de corps or a “band of brothers” mentality, the more cohesive a military unit is as an organization the more effective it is in combat.

But no matter how cohesive a unit is on the moral level, enough trepidation, defeat, attrition, frustration, and fear can overcome that cohesion. When that happens, individual members defect or retreat. Other units become isolated and distrust their adjacent and even higher counterparts. When the bonds of trust and loyalty within an organization are broken, it can no longer function as a whole. An army becomes individual corps, then depleted divisions, then broken and scattered remnants. As Marines evaluate and plan physical deployments with an eye toward affecting the enemy’s mind, it is their moral cohesion, which must be ceaselessly corrupted, dissected, and shattered and is the target of every tactical action, kinetic or non-kinetic.

Way Ahead

This article is the first in a series that will be published in the coming months. Each article will examine applications of MCDP 1, Warfighting through various lenses and against the background of 21st century warfare. These articles will include:

- 21st Century Combined Arms. As the method by which the Marine Corps executes maneuver warfare, the combined arms concept merits expansion to include emergent capabilities. What does combined arms mean in the 21st century?

- Maneuver. The Marine Corps uses maneuver to attack the enemy from a position of advantage. This advantage is not just spatial but must include out maneuvering the enemy on the cognitive level. How can the Marine Corps expand the maneuver space into other domains?

- Fires. Both surface-delivered and aerial-delivered fires affect the enemy and facilitate maneuver, but emergent capabilities can also contribute in a fires-like manner.

- Intelligence. Intelligence, as ever, will drive operations. How can the Marine Corps more quickly cycle through collection, analysis, and dissemination to drive the kind of rapid, dynamic operations required?

- C2. Information technology offers many opportunities, and threats, when it comes to command and control. The Marine Corps must continue to utilize a decentralized C2 method driven by mission command and commander’s intent but centralization is easier than ever. How can the Marine Corps avoid the temptation to micromanage?

- Logistics. All warfare depends on logistics, maneuver warfare included. The logistics community can leverage new technology to increase their agility and responsiveness, but that is only part of the answer. The Marine Corps has developed coordination between the GCE and the ACE into a fine art, how can it do the same for coordination with the LCE?

- Force Protection. Force protection extends across all Marine Corps functional areas, from fire support coordination to acquisitions to cyber defense. While it’s vital to protect Marine forces in the fight, force protection is continuous. How can we make more mentally resilient Marines before battle and better take care of them after?

- Amphibious Operations. How can emergent capabilities facilitate amphibious operations and how can the Marine Corps overcome adversaries ashore who employ capabilities and technology on par with our own?

Conclusion

Maneuver warfare, as a warfighting philosophy, is fit and appropriate for the strategic environment. Some aspects of MCDP 1 need a refresh. Others remain correct, but it is the institution that needs to better absorb the lessons.

The Marine Corps, as an organization is less strategically fit in the sense that institutional factors interfere with many of our philosophy’s tenets. Maneuver warfare is an ideal that we have yet to reach. This is not just a complaint but also an explication of a risk. As new Marines enter our Service and read our philosophy, they will compare their own experience with it. Every time a Marine does this and sees a breach between what the institution preaches and what it practices, the institution as a whole loses credibility. The bonds of trust between that individual and the Marine Corps are frayed and eventually broken. This is a threat to our moral cohesion as a fighting force and one that should concern all of us. MCDP 1 states that, “ … our philosophy demands confidence among seniors and subordinates.”27 Marine leaders who cannot lead in accordance with maneuver warfare, who persist in using authoritative and overly supervisory styles of command, are a threat to the institution as a whole.

Since maneuver warfare remains a sound approach to both war and warfare, the deficit between the status quo and strategic fitness is the Marine Corps’ collective ability to embrace its ideals in peacetime and in war. We must abide by and execute maneuver warfare as the character of warfare changes. In contrast to other Services, our philosophy primes us to not seek salvation in the form of wonder weapons or technological marvels. To be sure, we must exploit modern technology but do so in a way that enhances our warfighting capability while not depending wholly upon it. Rather, we look to improve ourselves and our organization, to invest in mental power rather than in purchasing power, and to out think rather than out buy. We must seek to do what the Marine Corps, starting with Pete Ellis, has done time and time again: integrate new technologies in innovative combinations with our storied traditions of excellence and Marines. Lastly, maneuver warfare teaches that we should invest heavily in our most significant asymmetric advantage: the United States Marine.

Notes:

You are the S-4a (Assistant Logistics Officer) for 1st Battalion, 1st Marines. You are an infantry 2nd Lieutenant, but when you graduated IOC, you took 30 days PCS leave, plus 8 days of travel and proceed. By the time you checked in to the battalion, there were no platoon commander assignments left unfilled. The battalion XO gave you a choice between Adjutant and S4a, and you obviously chose to support the Marines in the field the rather than do paperwork and make coffee for the XO.

You are the S-4a (Assistant Logistics Officer) for 1st Battalion, 1st Marines. You are an infantry 2nd Lieutenant, but when you graduated IOC, you took 30 days PCS leave, plus 8 days of travel and proceed. By the time you checked in to the battalion, there were no platoon commander assignments left unfilled. The battalion XO gave you a choice between Adjutant and S4a, and you obviously chose to support the Marines in the field the rather than do paperwork and make coffee for the XO.

Requirements:

Requirements:

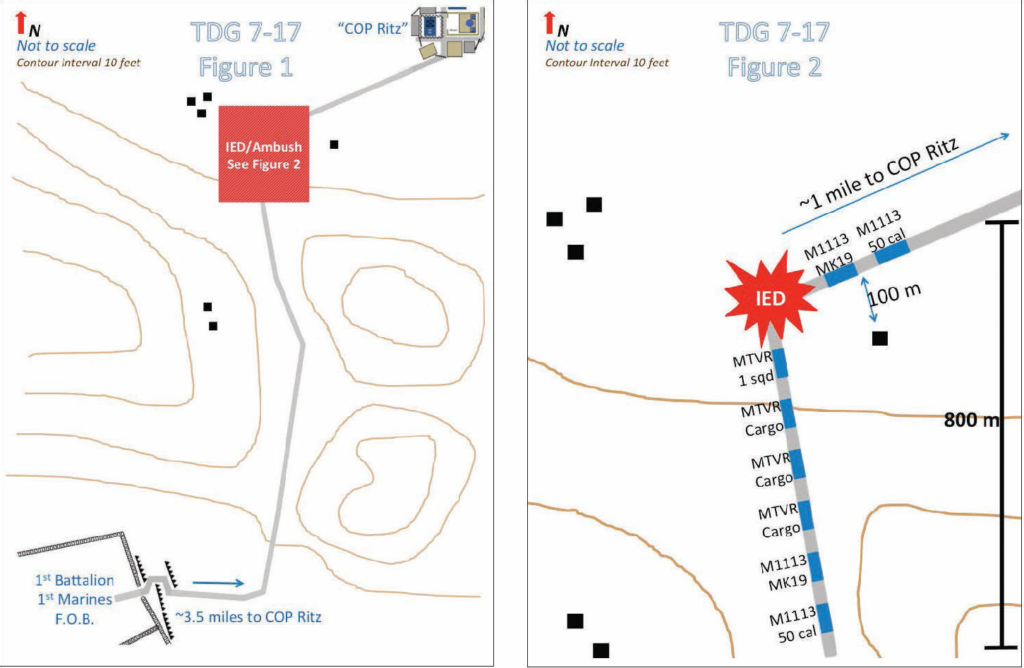

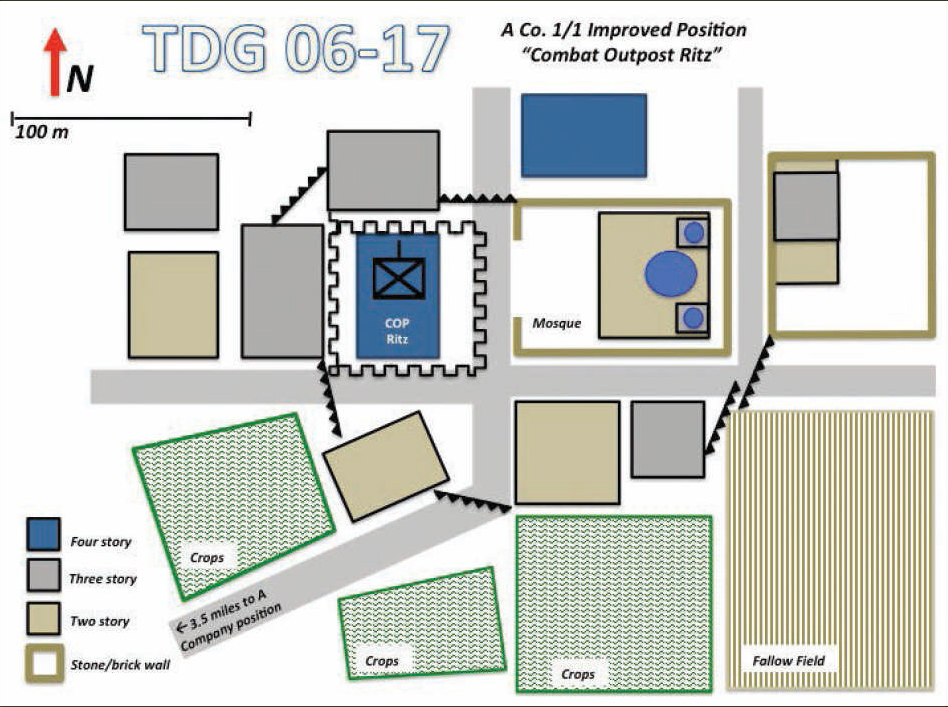

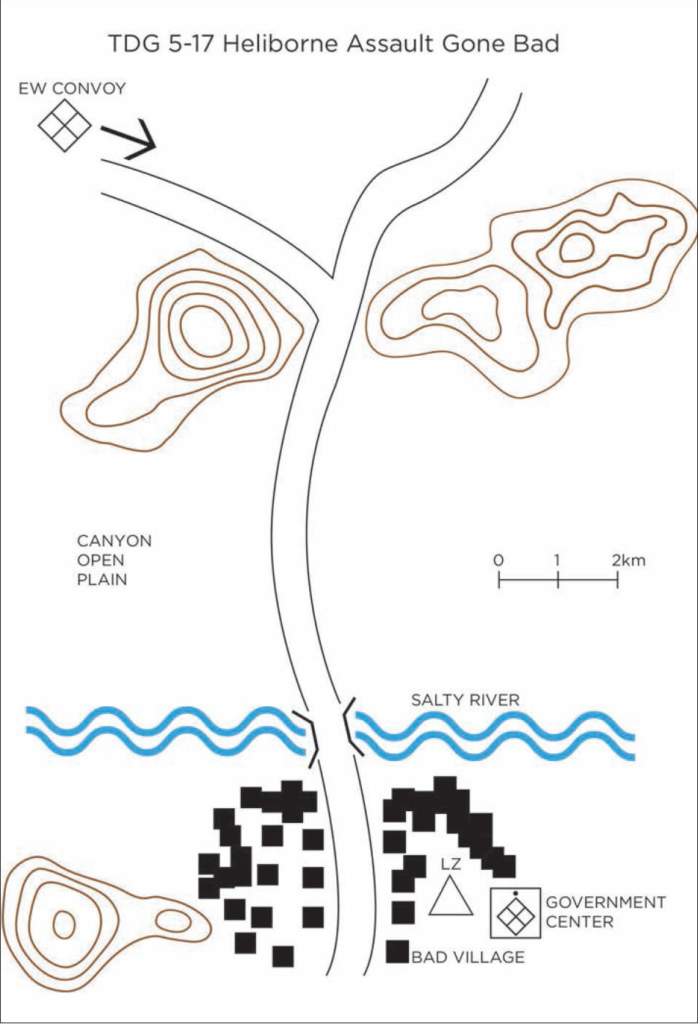

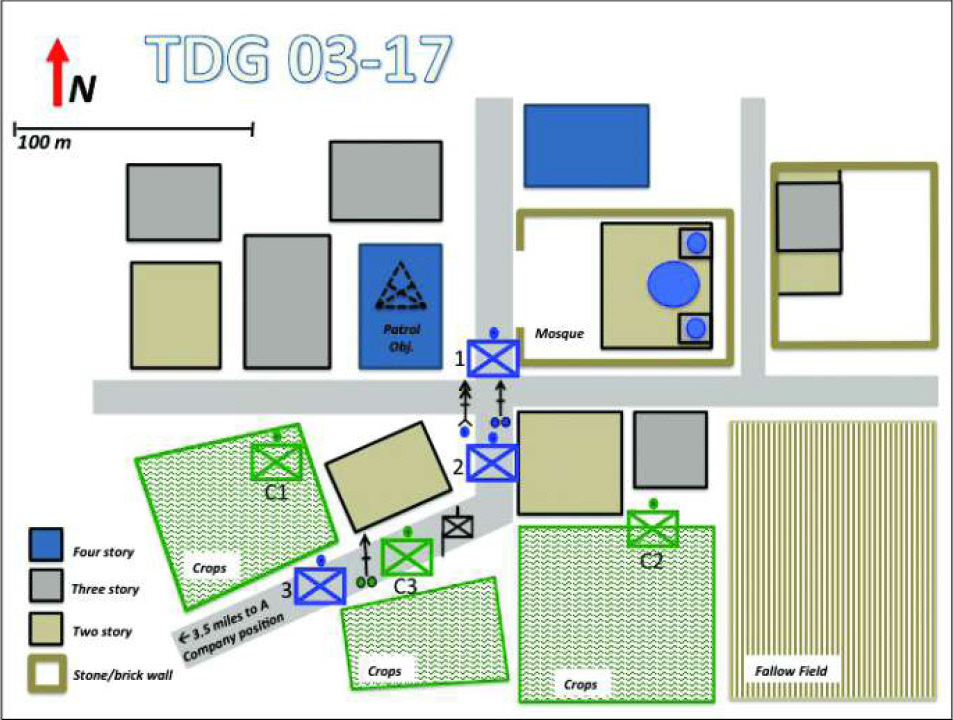

The 28th MEU is ashore in the country of Wasteland conducting counter-terrorist operations against a global network of religious extremists. Today, the BLT and ACE are conducting a heliborne assault into the village of Bad in order to establish a blocking position to deter an enemy attack from both Bad and through Canyon, a nearby valley. An enemy squad occupies the government center adjacent to local soccer fields, which are the primary landing zones.

The 28th MEU is ashore in the country of Wasteland conducting counter-terrorist operations against a global network of religious extremists. Today, the BLT and ACE are conducting a heliborne assault into the village of Bad in order to establish a blocking position to deter an enemy attack from both Bad and through Canyon, a nearby valley. An enemy squad occupies the government center adjacent to local soccer fields, which are the primary landing zones. Requirement

Requirement

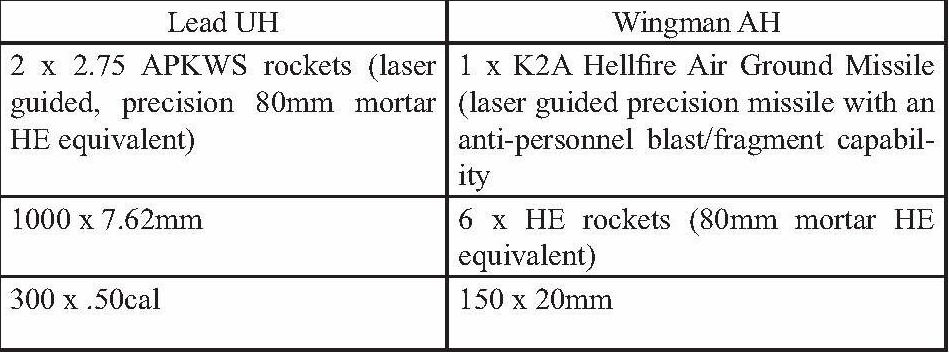

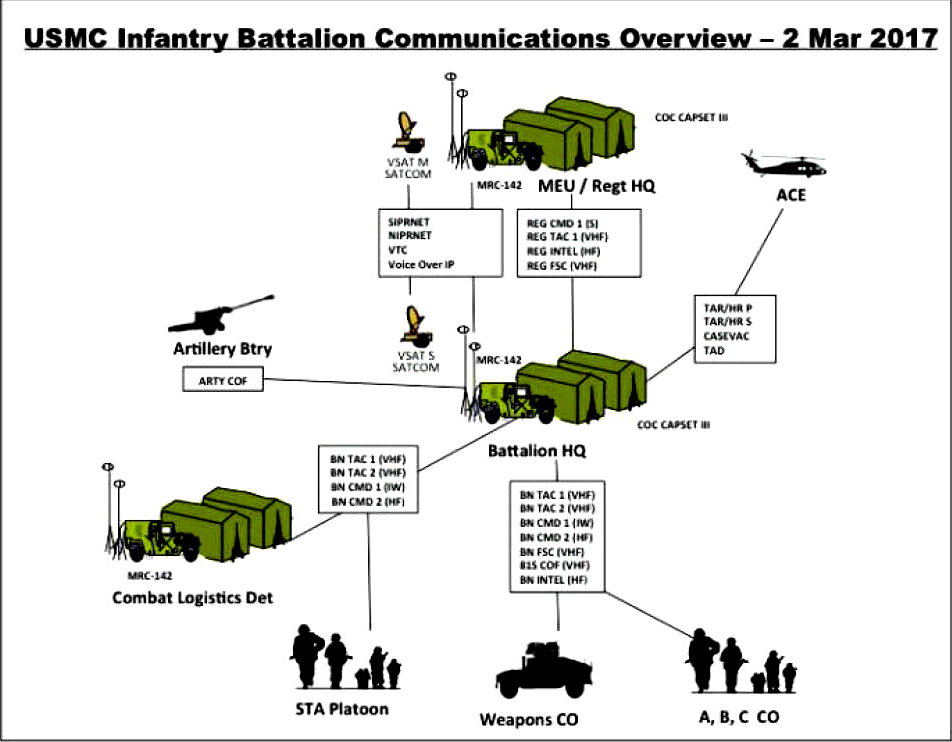

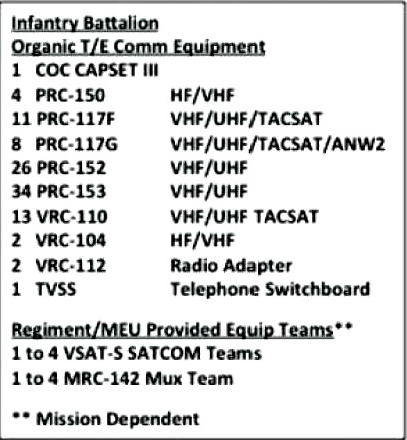

You have the following attachments and supporting arms available:

You have the following attachments and supporting arms available:

Requirement:

Requirement:

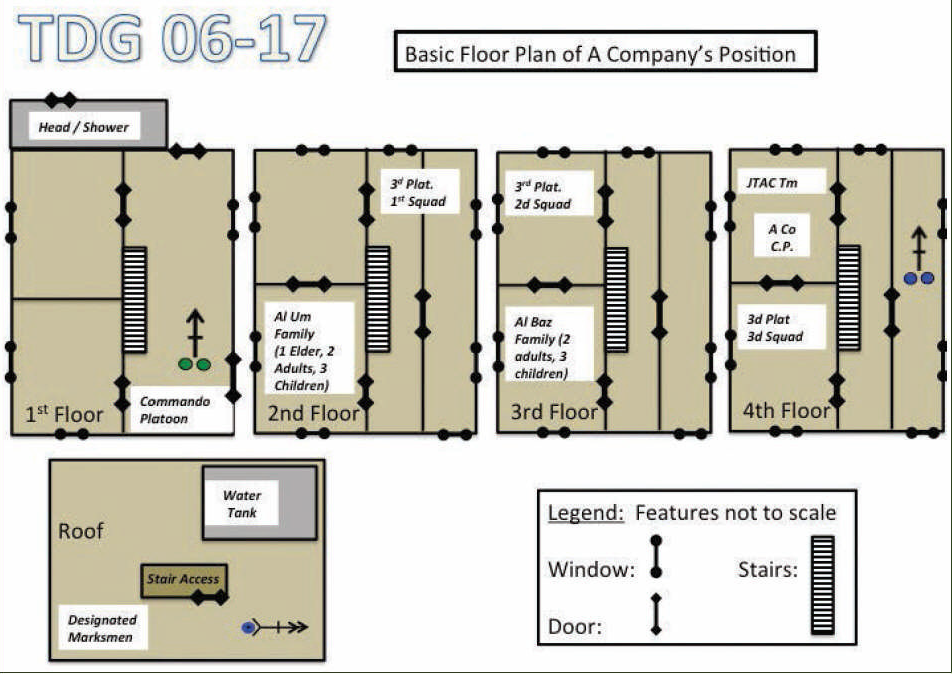

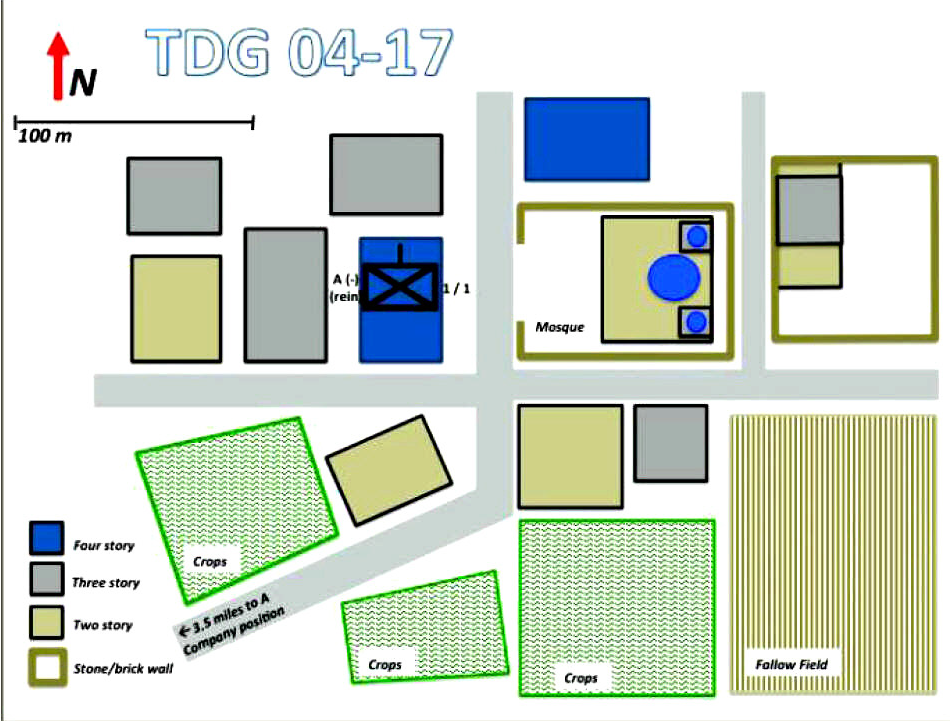

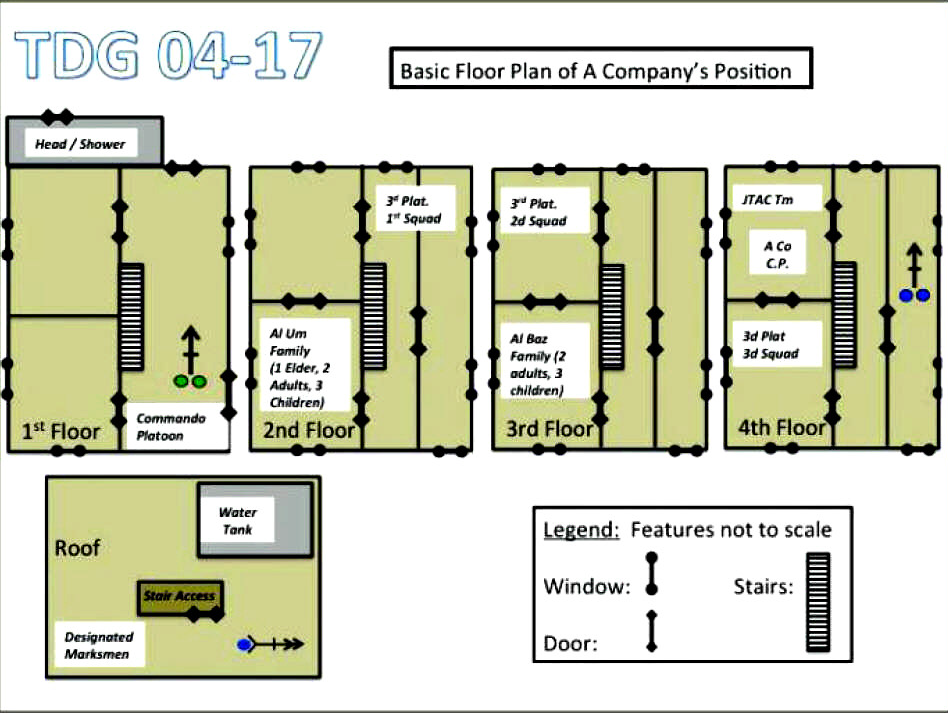

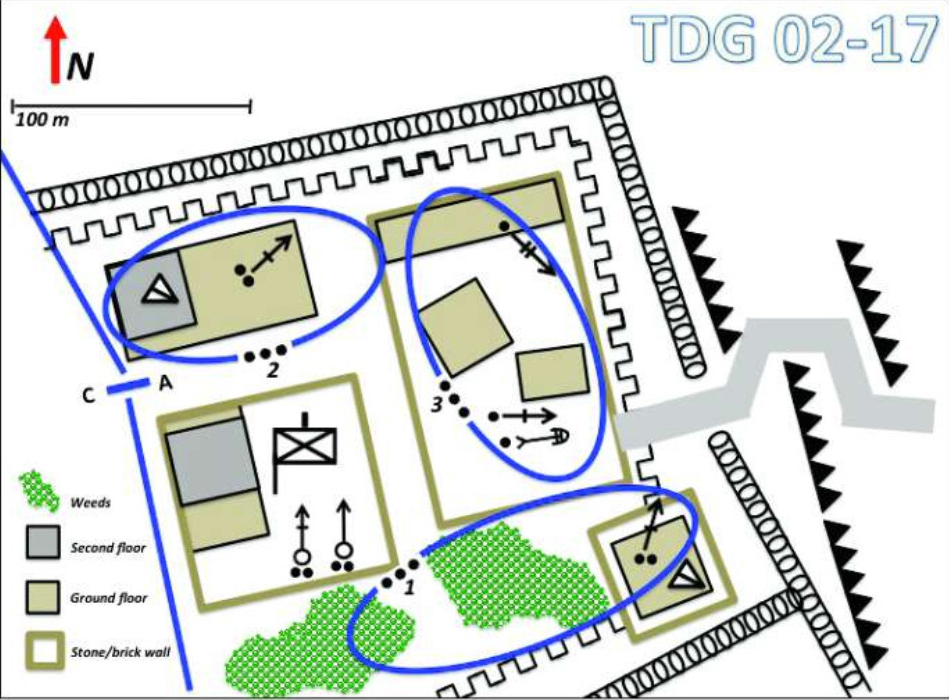

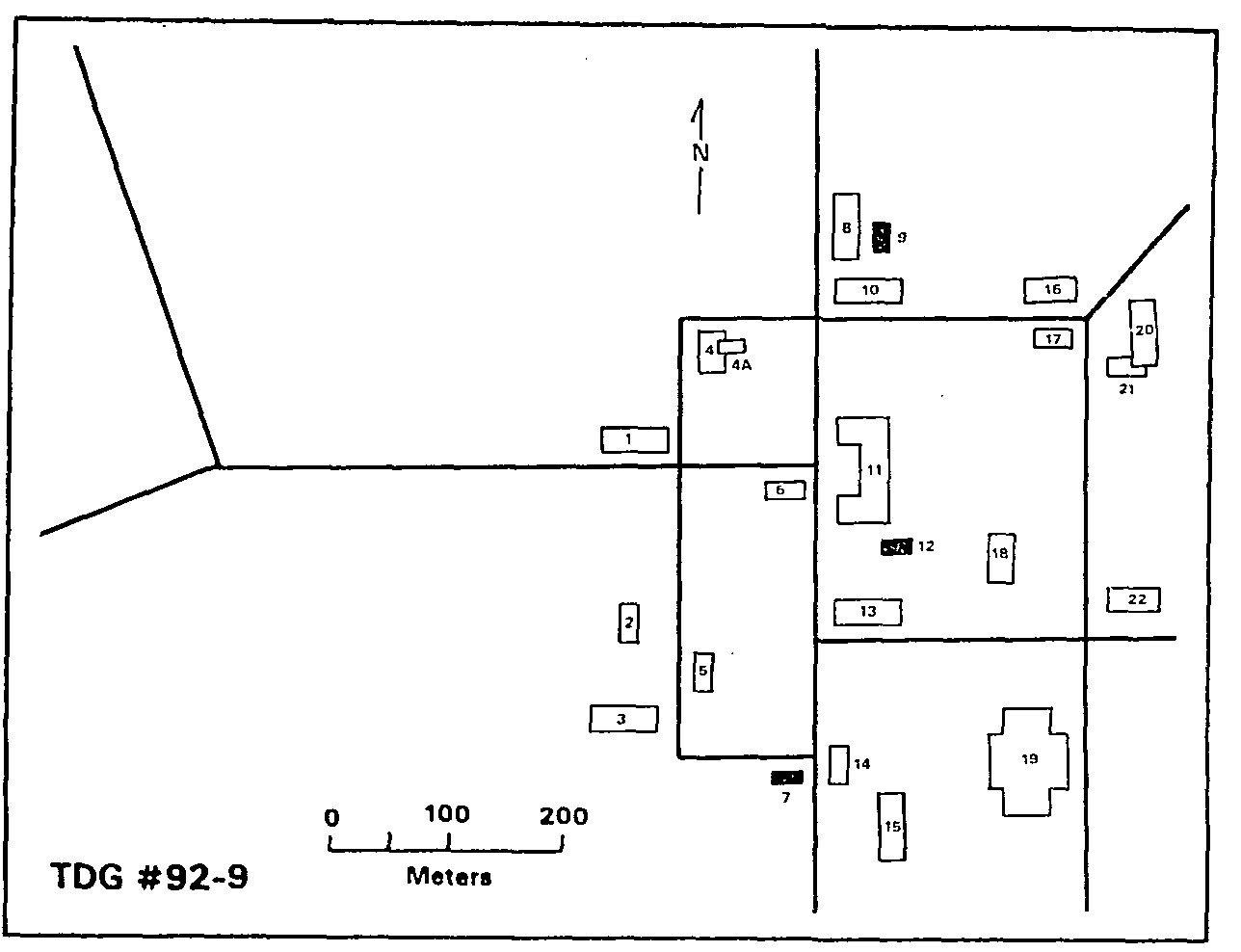

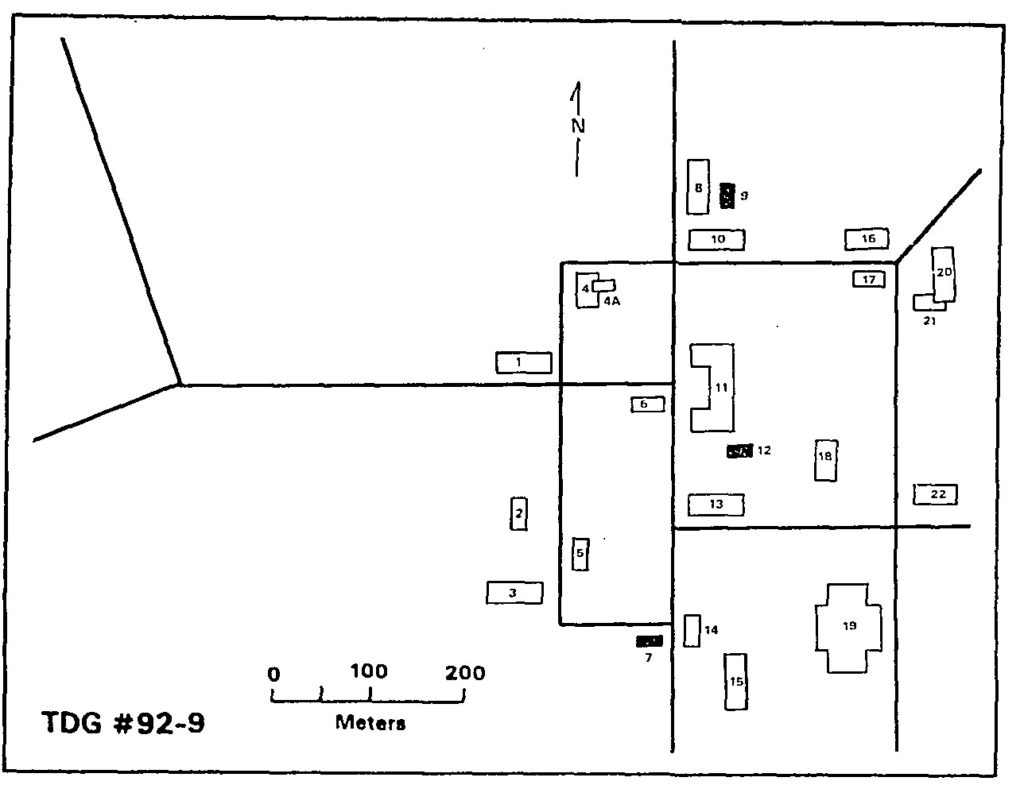

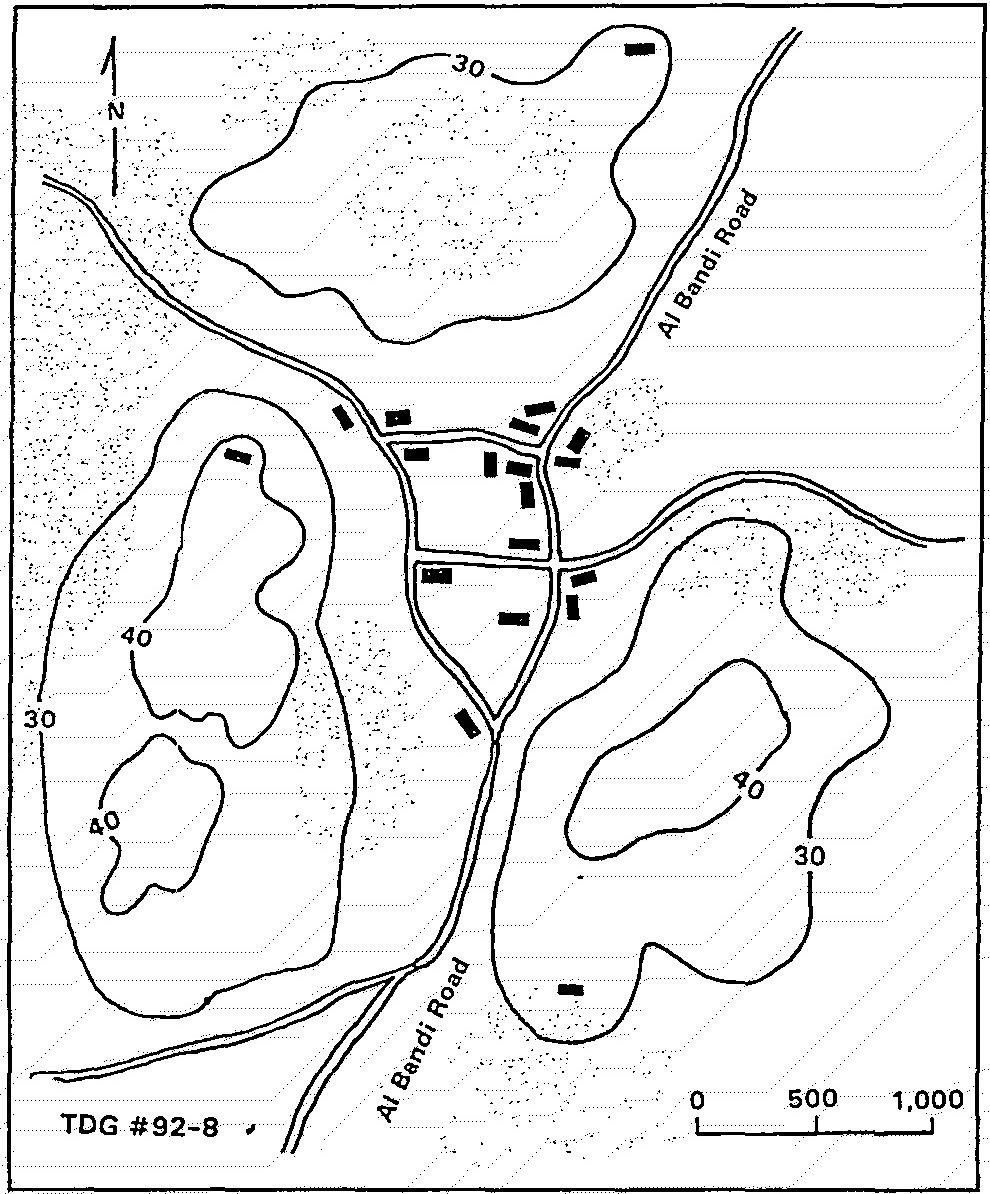

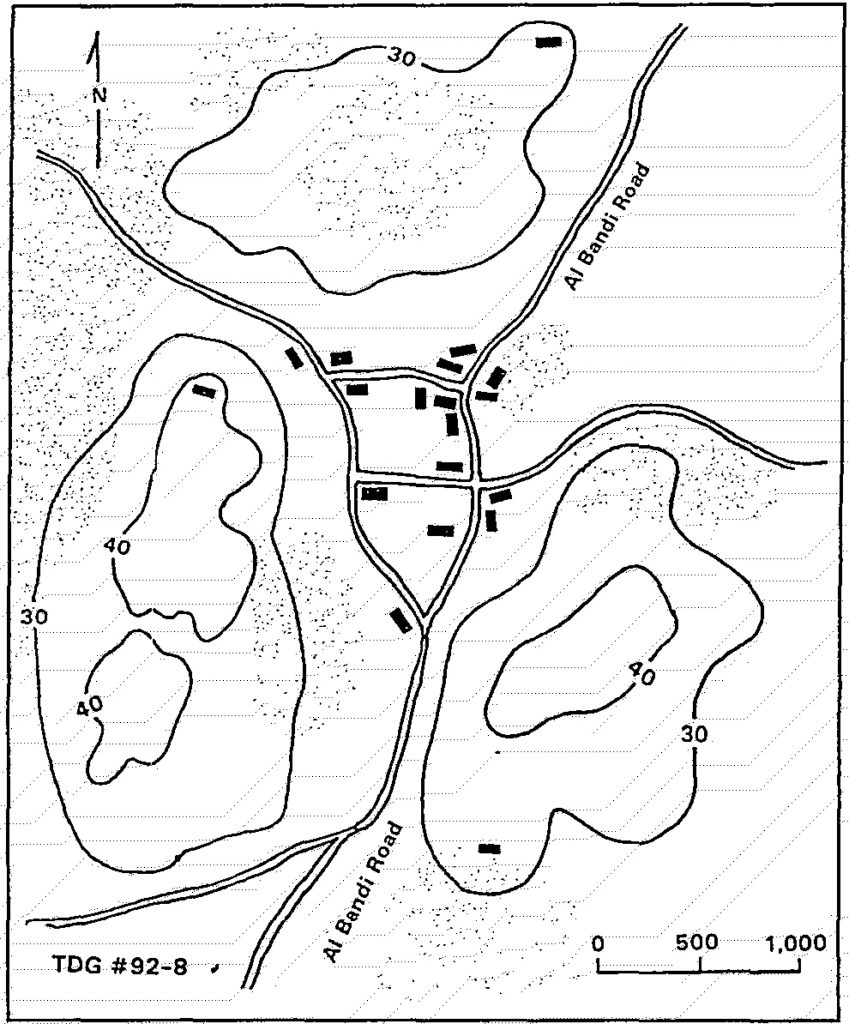

This is a continuation of the Dull Garrison Chronicles and takes place on the same terrain encountered in TDG #12-16R. It is the last of the Dull Garrison Chronicles.

This is a continuation of the Dull Garrison Chronicles and takes place on the same terrain encountered in TDG #12-16R. It is the last of the Dull Garrison Chronicles.

The 26th MEU has been directed to retake Dull Garrison Island (DGI) from the forces of BAD in order to rescue the beleaguered Marine garrison and to establish a foothold for follow-on forces. Elements of the 82d Airborne Division have begun to arrive and have taken up defensive positions around DGI Airfield #2. Things appear to be going well in that respect. For a time, the pressure on the flagging Marine provisional rifle battalion had slackened. In an apparent effort to wipe them out once and for all, however, the enemy redoubled their efforts against the garrison’s shrinking perimeter. The MEU commander, therefore, ordered a relief column to rescue the badly depleted battalion now located at Al Habib several kilometers south of Al Bandi.

The 26th MEU has been directed to retake Dull Garrison Island (DGI) from the forces of BAD in order to rescue the beleaguered Marine garrison and to establish a foothold for follow-on forces. Elements of the 82d Airborne Division have begun to arrive and have taken up defensive positions around DGI Airfield #2. Things appear to be going well in that respect. For a time, the pressure on the flagging Marine provisional rifle battalion had slackened. In an apparent effort to wipe them out once and for all, however, the enemy redoubled their efforts against the garrison’s shrinking perimeter. The MEU commander, therefore, ordered a relief column to rescue the badly depleted battalion now located at Al Habib several kilometers south of Al Bandi.