by Maj John F. Schmitt, USMCR

We all know how military decisions are made, right? At least we know how they are supposed to be made. Upon receiving the mission, the commander assembles the battle staff to analyze the mission-analyzing specified and implied tasks, arranging the task sequence, identifying constraints, and making assumptions. Next the commander and staff collectively determine information requirements about the enemy, the terrain, the weather, the local population, and so on. After that comes the staff orientation, a detailed description of the situation made mostly by the intelligence staff but with contributions from other staff sec tions, to ensure that everybody is “reading off the same sheet of music.” After the orientation the commander issues planning guidance, based upon which the operations _____ staff develops several potential courses of action and presents them to the commander. After the commander approves the courses of action, the various staff sections analyze them and provide estimates of suppoitability for each. Based on all of the preceding, the commander is now ready to make his estimate of the situation and announce his decision. If the process has worked properly, the decision is reduced to a matter of multiple choice-selecting from among the courses of action provided by the staff. From the commander’s decision and concept of operations the staff develops detailed plans that, upon the commander’s approval, are issued to subordinate units for execution. In theory, the same process will then occur successively in each unit down the chain of command.

The Classical, Analytical Decisionmaking Model

This is command and staff action done by the book-in this case the book is Fleet Marine Force Manual (FMFM) 3-1, Command and Staff Action-and it reflects the classical model of decisionmaking. (Command and staff action is merely a process for making decisions and communicating them to others in the form of orders or plans.) At the lower echelons of command where the commander lacks a full staff, he will perform many of these actions himself. At higher levels the process becomes a more formal interaction between commander and staff. But either way the object is the same: to take a methodical and efficient approach to decisionmaking and planning. We are taught that this is the “proper” way to make military decisions and to do any less is to “wing it” and to risk an ill-advised choice.

The classical model of decisionmaking holds that decisionmaking is a rational and systematic process of analysis based on the concurrent comparison of multiple options. The idea is to identify all the possible options, analyze all these options according to the same set of criteria, assign a value to each aspect of each option (either through quantitative means or subjectively), and choose the option with the highest aggregate value. In theory, this highest-value option is the optimal solution. In the research literature, this process is known as multiattribute utility analysis.

Say, for example, you want to buy a new midsized sedan within a certain price range for your family of four. You decide on a set of criteria-sticker price, fuel efficiency, roominess, warranty, safety, manufacturer’s reputation, buyer satisfaction-and you prioritize those criteria. Then you simply gather all the pertinent information about midsized sedans in your price range and compare. Some of the criteria are easily measured and compared-fuel efficiency, roominess, or dealer’s warranty, for example. Some of the criteria-such as carmaker’s reputation, safety, or buyer satisfaction-are less quantifiable, but you can still find reliable information on them in Consumer Reports or Car & Driver magazine. You weight the various criteria according to your established priorities, tally up the results, and as long as you have prioritized honestly, you will have the best choice for your new car. Thus the great appeal of analytical decisionmaking is that, as long as we have accurate information and do the analysis properly, it guarantees that we will reach the best possible decision. In other words, analytical decisionmaking seeks to “optimize.”

There are several other important characteristics of the analytical decisionmaking model that are important to understand. First, like most systematic and analytical processes, it is highly time consuming. It takes a while to identify, analyze, and compare all the various options. Using this model, you simply cannot make any decision until you have first analyzed all the options. As a result, no matter how quickly you can go through the process, there will always be a certain minimum amount of time that it takes to reach any decision. If timeliness is not a factor, this is not a concern; but if tempo is a key consideration, as it is in most military operations, this can be an overwhelming problem-in fact, in some cases it can short circuit the whole process.

Second, the analytical model requires a high level of certainty and accuracy of information. It assumes that, as with the sedan example above, the pertinent information will be available and reliable. It assumes that if the necessary information is not readily at hand then we will have the time and ability to find it. It is important to recognize that this consideration can significantly impact the previous one because it usually takes time to gather information. But whether it is due to the lack of time or not, if information is missing or unreliable, the quality of the decision suffers. The analysis and the resulting decision are only as precise as the information on which they are based. We can say with certainty that three plus five equals eight. But how many is a few plus a bunch? Moreover, where considerations are largely quantitative (as with the automobile example above), this process may work fairly well; but when considerations are qualitative, it will not. How do you assign a quantitative (or even subjective) value to the degree of flexibility or the element of surprise in each of your courses of action? It is a highly imprecise effort at best.

Third, reasoning power is essential to analytical ________ decisionmaking, but experience and judgment are not. The analytical model is process based. In theory, if you start with the right information and go through the analytical process properly, you are assured of getting the right answer regardless of your level of experience. As long as he has the requisite reasoning skills, a novice will reach the same answer as a seasoned military genius. To give an extreme example, a school child, as long as she has mastered the multiplication tables, will multiply six times seven and reach exactly the same answer as an Ivy League mathematics professor. The professor’s years of study will offer no more insight into six times seven. In other words, the process is specifically designed to eliminate intangible factors like judgment, intuition, and insight-factors which cannot be calculated.

We can readily understand the appeal of the analytical model. It depicts decisionmaking as a neat, clean, and orderly process that, properly executed, promises optimization. It is a thoroughly rational and systematic model that is attractive to our scientific society. It is easy to document and justify the analytical decision. (Advice: If cover-your-butt is a major concern, stick to analytical decisionmaking-you’ll always have an excuse.) And given the proper procedural training, practically anybody can master it.

The Problem: Reality Intervenes

The problem, as we all know, is that this process rarely works as advertised. Most military decisions are just not amenable to this type of approach. Military decisionmaking is not a neat, clean, and orderly process. Timeliness is a critical factor in most military decisions. Uncertainty and ambiguity are pervasive characteristics of practically all military decisionmaking. Unlike selecting a new car, military decisionmaking is not a matter of choosing from among a finite number of already existing optionsmilitary decisionmaking is not multiple choice. Rather, it is a matter of creating a unique solution out of countless unclear possibilities, based largely on unquantifiable factors. Our own experiences tell us that humans rarely make decisions by multiattribute utility analysis. (In 12 years as an active duty infantryman, I can recall only one time that I actually went through the process of comparing two options concurrentlyand ended up going with my gut instead of my analysis anyway.)

What typically happens is that we lack the time and information necessary to do justice to the analytical process. We end up combining, skipping, or hurrying steps-in general trying to “crunch” the process to fit into the time availableand often feel guilty that we have not done things the way we think we are supposed to. Since we are taught to believe that rational analysis is the right way to make any decision, if the decision does not work out well, more often than not we conclude that it was because we did not go through the prescribed steps properly. If only we’d had more time to do all the steps. If only we’d done a more thorough analysis.

We need to realize, even if we have the time and do the analysis, the results will rarely be optimal. There are two basic reasons for this. First, there are rarely any absolutely right or wrong answers when it comes to tactics, operations, or strategy-rarely any optimal solutions. In the words of Gen George S. Patton: “There is no approved solution to any tactical situation.” And because time is usually a critical factor, “better” is often the ruin of “good enough.” To quote Patton again: “A good plan violently executed now is better than a perfect plan next week.” Second, while the analytical process may be precise, it will usually be based on considerations that are extremely difficult to quantify and are often no better than subjective hunches-considerations, in other words, which are very imprecise. No matter how exact the process, the results will be no more precise than the starting assumptions-or, in the lingo of computer programmers, “garbage in, garbage out.” So despite its theoretical promise, the analytical approach to military decisionmaking is no more certain to achieve optimal results in practice than are other methods that do not try to optimize.

And perhaps most important of all, the undeniable reality is that human beings simply do not make decisions this way. The analytical decisionmaking model has little in common with how the human brain actually works in most circumstances. Fortunately, humans are not nearly the rational animals that we like to think we are. We have the capacity to act rationally, certainly, but it is hardly the only way-or in the main way-our brains work. So how do we actually make decisions?

Intuitive Decisionmaking

Starting in the 1970s, cognitive psychologists began in earnest to question the classical decisionmaking model and started studying how experienced decisionmakers made decisions in “real life” situations. The phrase “naturalistic decisionmaking” was eventually coined to distinguish between this new approach to decisionmaking theory and the classical approach. While the classical approach studied decisionmaking under controlled conditions in an attempt to remove environmental and intangible factors, the new school sought to study decisionmaking under “naturalistic” conditions. Specifically this meant decisionmaking characterized by:

* Ill-structured, situation-unique problems.

* Uncertain, dynamic environments.

* Shifting, ill-defined or competing goals.

* Lack of information.

* Ongoing action with continuous feedback loops (as opposed to a singledecision event).

* High-level stress and friction.

* Time stress.

Not surprisingly, the research revealed that proficient decisionmakers rarely make decisions by concurrent option comparison. Instead, they use their intuition to recognize the essence of a given situation and to tell them what appropriate action to take. In fact, separate studies by Dr. Gary Klein and others conclude that decisionmakers in a variety of fields use the analytical approach to decisionmaking less than 10 percent of the time and employ intuitive techniques over 90 percent of the time.* Experienced decisionmakers will tend to rely on intuitive decisionmaking to an even greater extent than that, while inexperienced decisionmakers are more likely to use the analytical approach (although still not nearly as often as the intuitive method).

Klein developed the recognitionprimed decision (RPD) theory, which has become one of the most widely recognized of the intuitive decisionmaking theories (and which has led to the field sometimes also being known generically as “recognitional decisionmaking”). Others in the field developed other theories known by different names, but all the theories are similar in that they emphasize intuitive situation assessment as the basis for effective decisionmaking. Klein and colleagues concluded that proficient decisionmakers rely on their intuition to tell them what factors are important in any given situation, what goals are feasible, and what the outcomes of their actions are likely to be-allowing them to generate a workable first solution and eliminating the need to analyze multiple options. Whereas the emphasis in analytical decisionmaking is on the systematic comparison of multiple options, the emphasis in intuitive decisionmaking is on situation assessment-or, in military terminology, situational awareness or coup d’oeil. In other words, based on a firm understanding of the true situation, the decisionmaker knows intuitively what to do without having to compare options. Where analytical decisionmaking strives to “optimize,” intuitive decisionmaking seeks to “satisfice”-to find the first solution that will work. By its nature, intuitive decisionmaking is much faster than analytical decisionmaking and copes with uncertainty, ambiguity, and dynamic situations more effectively. When it comes to the conduct of military operations, these are two huge advantages.

The intuitive decisionmaker may actually consider more than one option out in series rather than concurrently. For example, he considers option A: if experience tells him A will work, he executes it; if not he moves on to option B. If B will work, execute; if not, consider option C. And so on. This would seem to indicate that the quality of the decision depends on the random order in which options are considered. Option C may be the best solution in theory, but it is never even considered because B is good enough. In practice this is not really a problem, however, because in the Friction of the battlefield, “optimal” solutions rarely live up to expectations, and good enough is just that-good enough. Moreover, the process does not seem to be random after all. Evidence suggests that proficient decisionmakers tend to consider an effective option (if not the “best” one) first.

The essential factor in intuitive decisionmaking is experience. This is an extremely important point. Experience is the thing that allows for the situation assessment that is at the heart of intuitive decisionmaking. Experience allows us to recognize a situation as typical-that is, within our range of understanding. Although each situation is unique, experience allows us to recognize similarities or patterns and to understand what those patterns typically mean. If we have sufficient experience (and have learned by it) we do not need to reason our way through a situation, but instead simply know how to act appropriately. In general, the greater the experience, the greater the understanding-like the chess master who (studies show) can understand the “logic” of up to 100,000 different meaningful board positions. It is this experience factor which, more than any other, facilitates the pattern-recognition skills or coup d’oeil that are the hallmark of brilliant military minds.

Comparing The Two Models

This is not to suggest that intuitive decisionmaking is always superior to analytical decisionmaking. Each of the models has strengths and weaknesses. One of the keys to effective decisionmaking, therefore, is to know what type of decisionmaking is appropriate to a given situation.

There are circumstances in which the analytical approach offers advantages. Specifically, analytical decisionmaking offers advantages when:

* Time is not a factor-during prehostility contingency planning, for example.

* Decisionmakers lack the experience needed for sound intuitive judgments.

* The problem poses so much computational complexity that intuitive processes are inadequate-detailed mobilization planning, for example.

* It is necessary to justify a decision to others or to resolve internal disagreements over which course to adopt.

* Choosing from among several clearly defined and documented options-such as in deciding from among several equipment prototypes in the procurement process.

So clearly there are circumstances in which analysis helps. Having said that, however, the really important point is that intuitive decisionmaking is far superior to analytical decisionmaking in the vast majority of typically uncertain, fluid and time-sensitive tactical situations. The implication of this is clear: the Marine Corps must start to develop intuitive decisionmaking skills among its leaders.

It is also important to recognize that, while conceptually opposite, the two models are not mutually exclusive in practice. It is possible, for example, to incorporate analytical elements as time permits into what is essentially an intuitive approach. So in any given situation we have to ask ourselves: Is analysis appropriate? Will intuition work best? Or, what combination of the two does the situation require?

How To Teach/Learn Intuitive Decisionmaking

There can be no doubt that we do an excellent job of teaching analytical decisionmaking in our professional schools. Of course, this is only to be expected given the amount of time and effort we dedicate to the subject. But we have to question the wisdom of devoting so much time and effort to teaching a method we will use less than 10 percent of the timeand in the process reinforcing the mistaken belief that the analytical approach is the “right” way to make decisions. This emphasis on analytical decisionmaking in the schoolhouse is especially questionable when we consider that by comparison we spend little or no time at all teaching our decisionmakers the techniques they will need over 90 percent of the time. Clearly, the time has come for a serious reassessment of how we approach and teach command and staff action-the time has come to start introducing intuitive decisionmaking in a serious way and to give it priority in our schools.

Some would argue that we have to teach analytical decisionmaking before we can teach intuitive decisionmaking because the analytical decisionmaking procedures constitute the “building blocks” of decisionmaking-as if intuitive decisionmaking is merely analytical decisionmaking done subconsciously and more quickly; as if you cannot do intuitive decisionmaking until you have mastered analytical decisionmaking. To argue this is to misunderstand the fundamental differences between the two models. Intuitive decisionmaking is not merely analytical decisionmaking internalized. The two types of decisionmaking are fundamentally different types of mental activity, based on entirely different intellectual qualities. Analytical decisionmaking is a rational, calculating activity-it is essentially scientific. Intuitive decisionmaking is an arational (but not irrational), sensing activity-essentially artistic.

Others will argue that if the process is intuitive, then there is no need to teach it because people will do it naturally. But while the process may be intuitive, the experience and judgment on which it is based are not. Those qualities must be acquired, and as we will discuss, there is no other way to acquire them than through repeated practice. Moreover, just because we do something intuitively does not mean that we cannot learn to get better at it. The bottom line is that if we want to develop masters in the art of command, we should start teaching Marines intuitive decisionmaking from the beginning. Now, this is not to advocate that we abandon analytical decisionmaking altogether; only that we subordinate it to more important (and more frequently used) decisionmaking skills.

The first thing we have to do is to recognize as an institution that human beings have an intangible capacity for intuition that can outstrip even the most powerful analysis. We have to recognize that even though we cannot fully understand or explain it, this skill can achieve superior results. It is not mystical or merely theoretical. It is real. It is a documented capability of the human mind, and we have to be committed to exploiting and developing it.

Being committed to intuitive decisionmaking, how do we teach it? One thing is clear: we cannot teach it the same way we teach analytical decisionmaking. Because analytical decisionmaking is process based, the way to teach it is to teach the process. This is exactly what we do in our schools. But this approach makes no sense with intuitive decisionmaking precisely because the process is intuitive. In fact, we can even argue that intuitive decisionmaking is a skill that cannot be taught per se (as in provided by the teacher to the student), but rather that intuitive decisionmaking can only be learned (as in gained by the student by his or her own effort). With that in mind, there are two important considerations in learning intuitive decisionmaking. First, like most skills, decisionmaking is a skill that improves with practice. Even when we perform a skill without consciously thinking about how-swinging a tennis racquet, solving a crossword puzzle, playing Nintendo Gameboy-we intuitively learn to perform that skill more efficiently simply from repeated practice. Second, as we mentioned earlier, intuitive decisionmaking is an experiencebased skill. A broad base of experience is essential to the coup d’oeil or skill for pattern recognition that is in turn the basis for intuitive decisionmaking; the way to improve intuitive decisionmaking is to improve pattern recognition; the way to improve pattern recognition is to improve the experience base.

In either event, the way to learn intuitive decisionmaking is to practice decisionmaking repeatedly in an operational context. This is a point not wasted on other disciplines. A few years back the Harvard Business School adopted a case study approach to its MBA program. In the first year of the 2-year program, MBA students do not take classes on economics or business management theory per se. Courses consist of business case studies, which the students pick apart from a management point of view. Each class period is devoted to a different case, and students are expected to be able to discuss that case intelligendy as the basis for their course grades. It is only in the second year, after they have a firm grounding in numerous historical cases, that students take courses in business theory-although they also continue with case studies. By the end of the second year, Harvard MBA students have studied some 240 business cases. One of the things that makes Harvard MBAs so desirable in the business world is that they have a broad base of practical understanding of business decisionmaking.

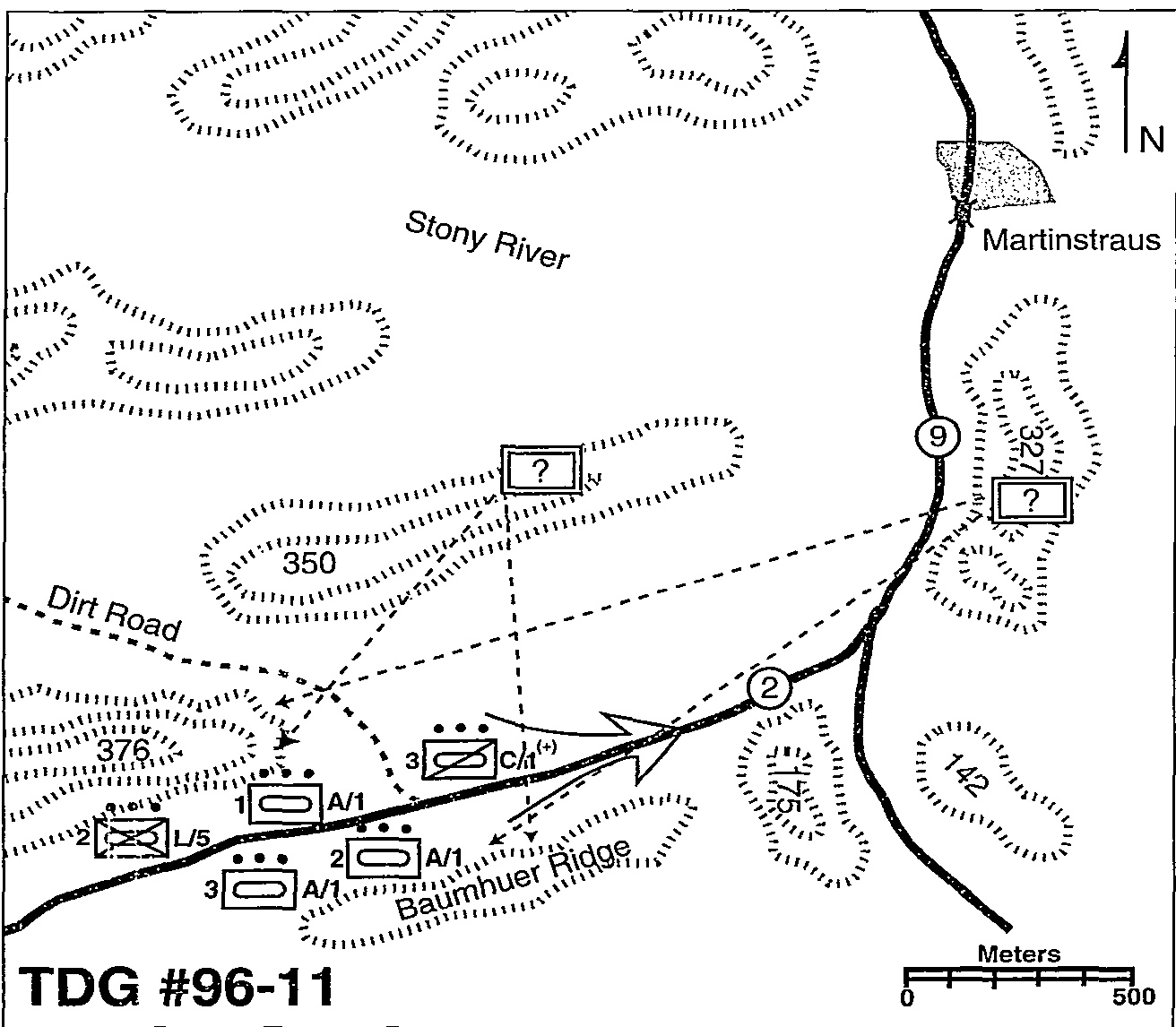

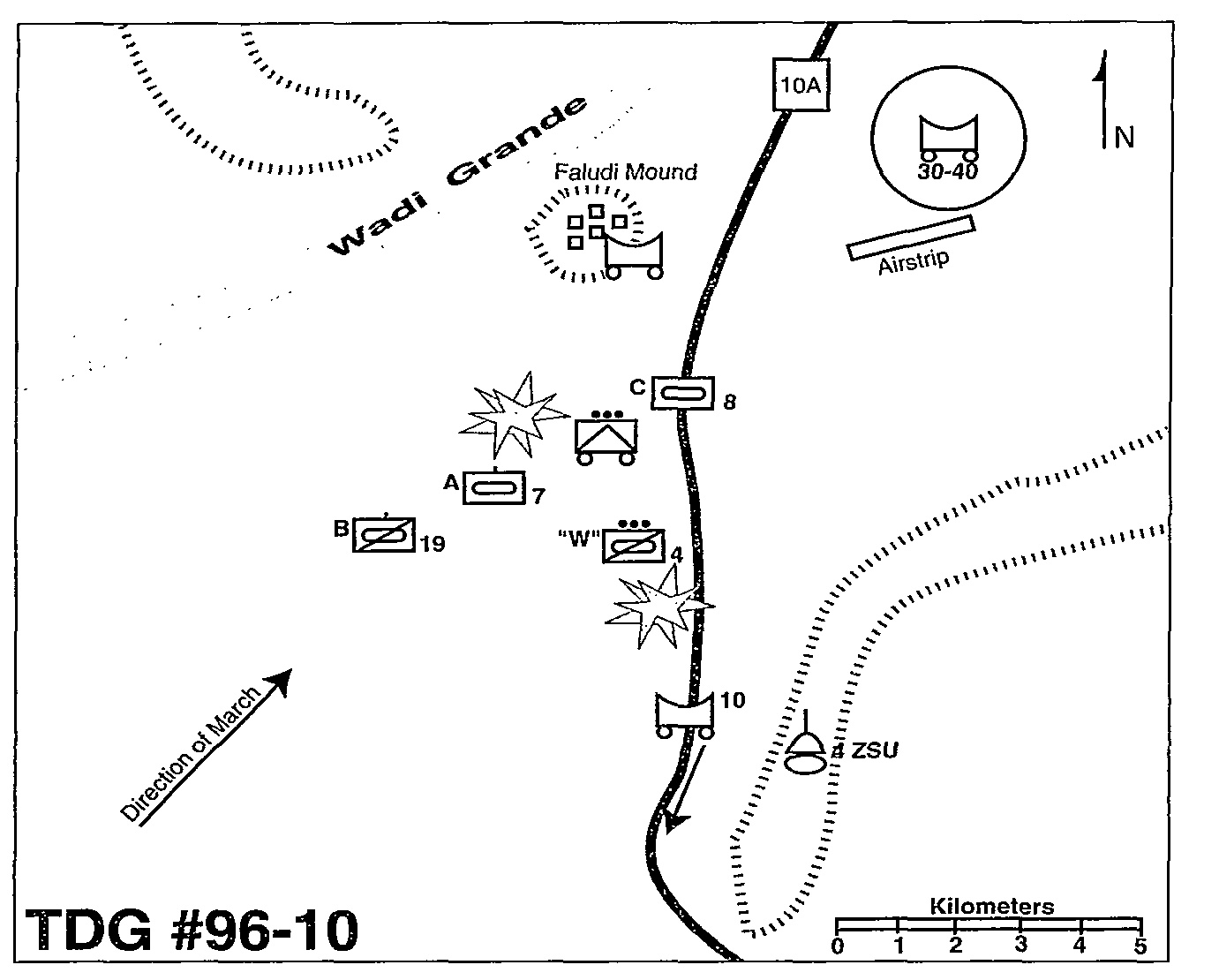

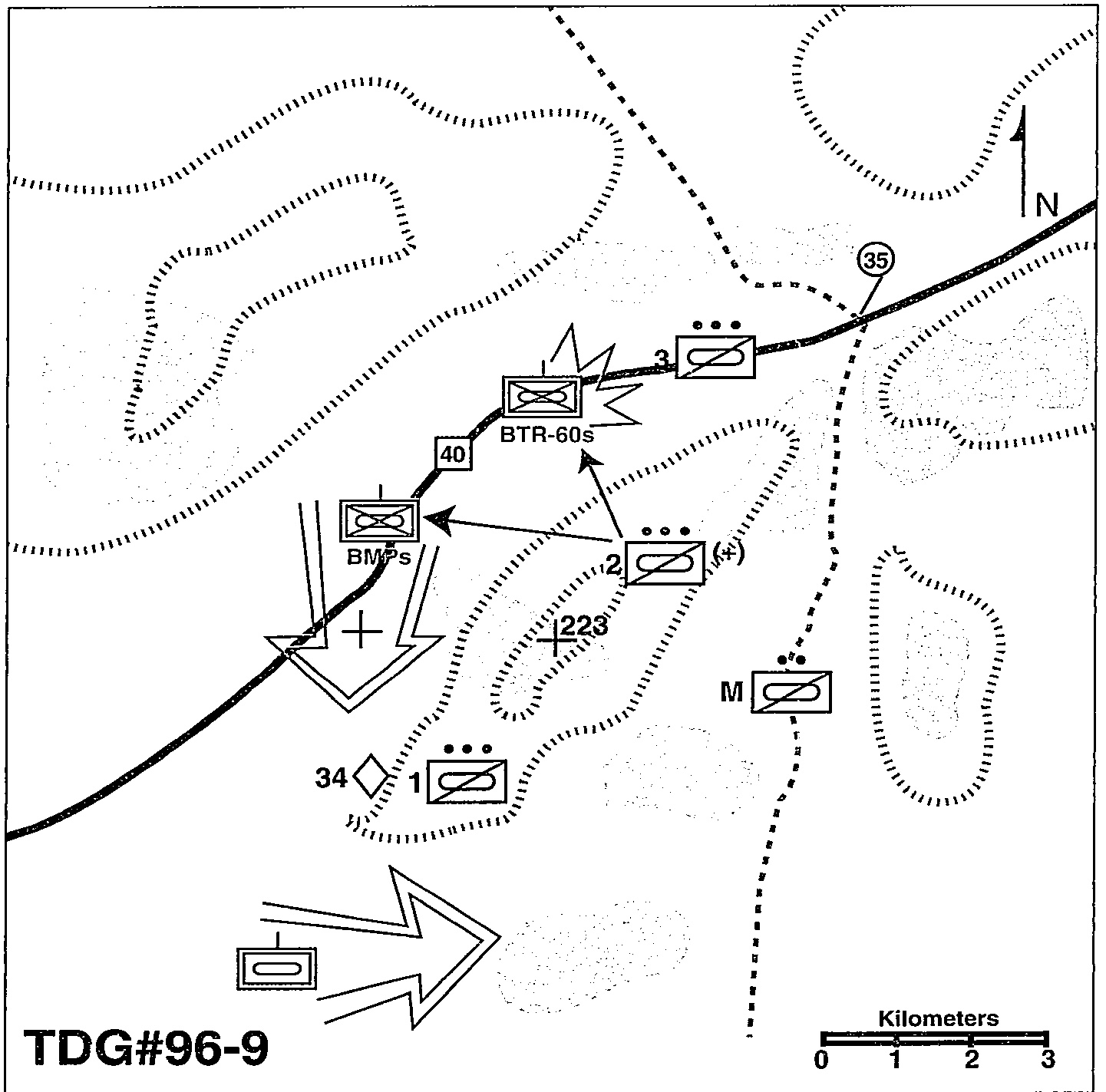

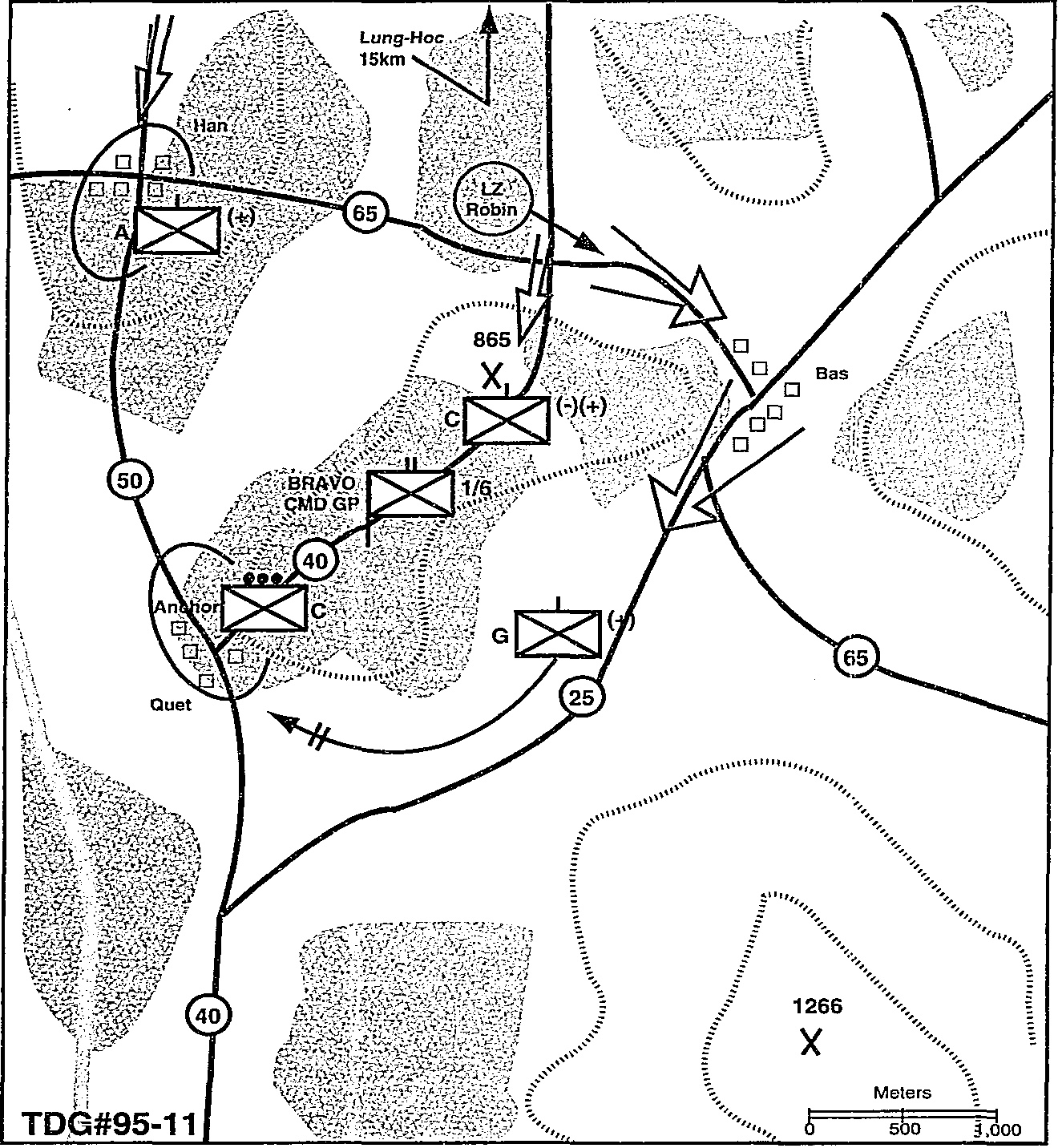

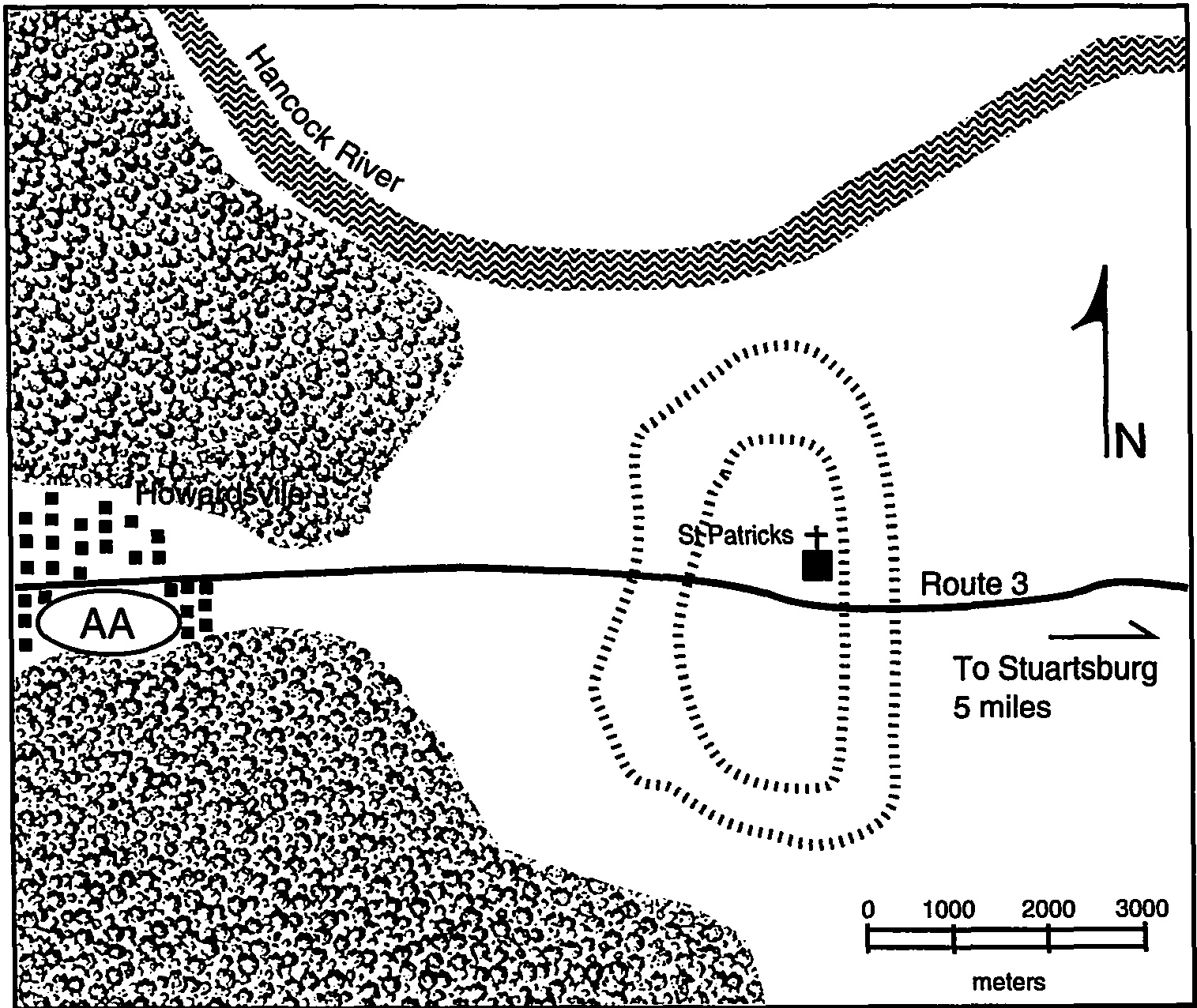

We should take the same approach in preparing our decisionmakers. We should repeatedly put our commanders in the position of having to make tactical, operational, and strategic decisions of all different sorts. This means that we should make extensive use of case studies-battle and campaign studiesviewed from the perspective of command decisionmaking. We should make extensive use of tactical decision games (TDGs) and other war games. For example, every day spent in the classroom at any Marine Corps school should begin with an appropriate level half-hour TDG session. (I mention TDGs specifically because they are much easier to do in a short period of time than other decision exercises and offer a higher yield in terms of decisionmaking experience.) It is not enough to do the occasional case study or TDG: these must become a near-daily session in order to amass the requisite experience base. Breadth of experience is more important than detail of experience. From a decisionmaking perspective, 10 different TDGs are more valuable than a single full-scale, computerized wargame in the same period of time.

Moreover, each decisionmaking exercise should be a high-risk experiencemeaning that the decisionmaker should feel the pressure of being “put on the spot.” This is important both to simulate the stress that is a main feature of most military decisionmaking and to provide a heightened learning incentive. Each decisionmaking experience should involve a discussion/critique led by a more experienced Marine to provide evaluation and draw out the key lessons, for while it is true that a person will learn simply by his or her own experience, the learning curve will be higher with wise guidance. It is also best to play TDGs in a group so we can see how others solved the same tactical problems and can incorporate those lessons to our own experience. The same principle applies outside the schoolhouse-in the Fleet Marine Force or anywhere else. All Marines should be exercising their decisionmaking skills on a daily basis and adding to their reservoirs of experience.

Summary

Recent developments in the area of decisionmaking research show that humans rarely make decisions the way we have long assumed they do. Effective decisions in the uncertainty, fluidity, and stress of war have more to do with insightful intuition than with systematic analysis. Likewise, creating effective decisionmakers has more to do with developing coup d’oeil than with teaching process. It is time for the Marine Corps to recognize this and take a hard look at how we train our commanders.