By LtCol Philip Anderson

MCU’s focus on combat decisionmaking is unique to its academic environment. Unlike other universities in which students possess a wide variety of goals and pursue numerous educational disciplines, the audience and subject matter at MCU are fixed and representative of the Marine Corps’ unique military society where students are . . . focused on improving their ability to succeed in battle.

During the 1930s, as the assistant commandant of the United States Army Infantry School, GEN George C. Marshall (then a colonel) put together a faculty of proven officers. Together they set about teaching students to think clearly about the battlefield. This faculty, through the use of some simple and practical teaching methods, realized great success. The purpose of this article is to offer some suggestions for teaching this generation of Marines. Much of what will be presented here is not new and may seem obvious to some readers familiar with history and/or educational theory and practice. However, the objective is not to restate what has already been written, but rather to assemble the aspects of the conventional wisdom most appropriate for promoting effective teaching among faculty in the Marine Corps University (MCU) environment.

Teaching has been defined throughout history as both an art and a science. Many modern educators define teaching simply as the means by which we educate or through which knowledge is imparted to students. The fact of the matter is that teaching at MCU must be more significant. The end result of effective teaching and the object of professional military education (PME) should be to unify the efforts of the faculty toward providing a foundation or framework from which students can develop their ability to make effective decisions in all situations up to and including combat. This differs from other applications in its audience and subject matter. MCU’s focus on combat decisionmaking is unique to its academic environment. Unlike other universities in which students possess a wide variety of goals and pursue numerous educational disciplines, the audience and subject matter at MCU are fixed and representative of the Marine Corps’ unique military society where students are focused on improving their ability to succeed in battle.

In the Marine Corps our warfighting philosophy is based on our understanding of the problems of uncertainty and friction on the battlefield. At the heart of our warfighting philosophy is the fact that decisionmaking in this environment, under trying conditions, is most often affected by intangible or imprecise factors. In this regard, PME should create a climate conducive to addressing the intangible subjective aspects of combat decisionmaking. Under Marshall, students were often issued foreign or outdated maps, provided incomplete intelligence information, compelled to operate without communications, given little time to plan and routinely made to contend with the unexpected. His faculty emphasized ingenuity and imagination. One of Marshall’s first orders was that any student’s solution that ran counter to the approved school solution and yet showed independent creative thinking would be published to the class.’

Education Versus Training

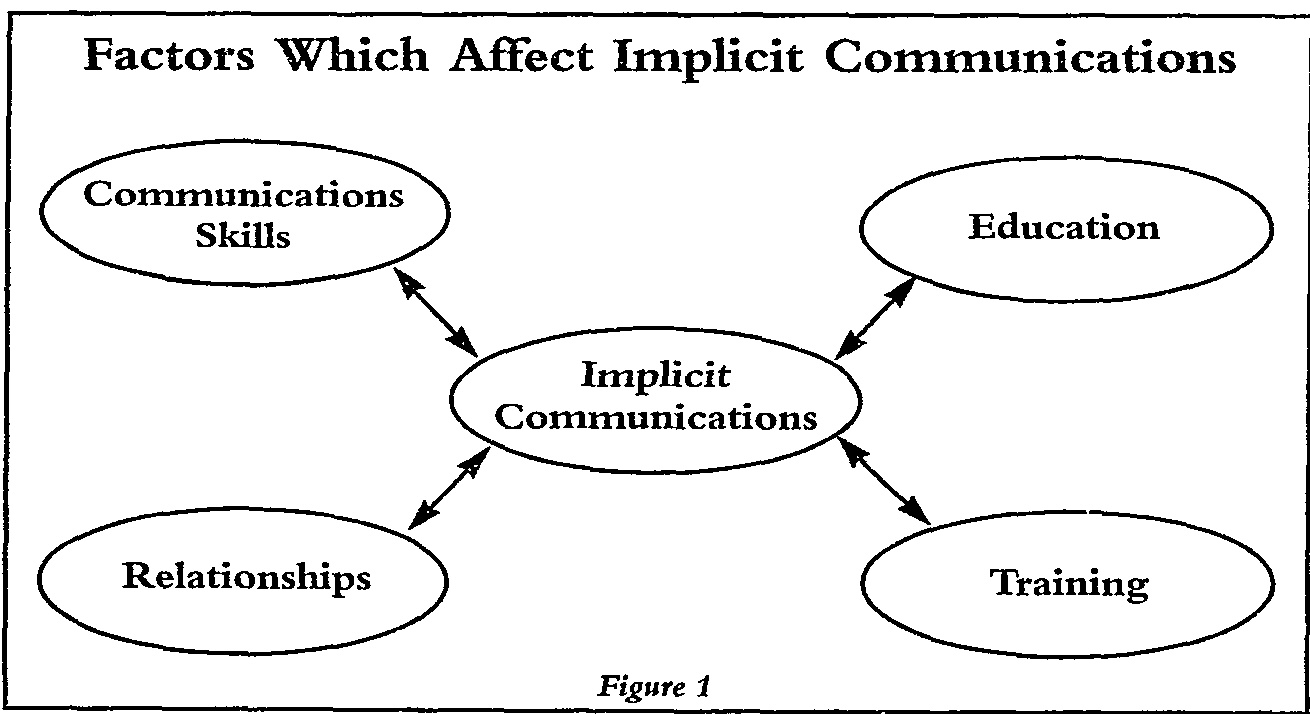

The debate continues regarding how to differentiate between technical ability generally acquired through “training” and the intangible human qualities generally developed through “education.” Nonetheless, it is important to possess a clear understanding of how each interrelates.

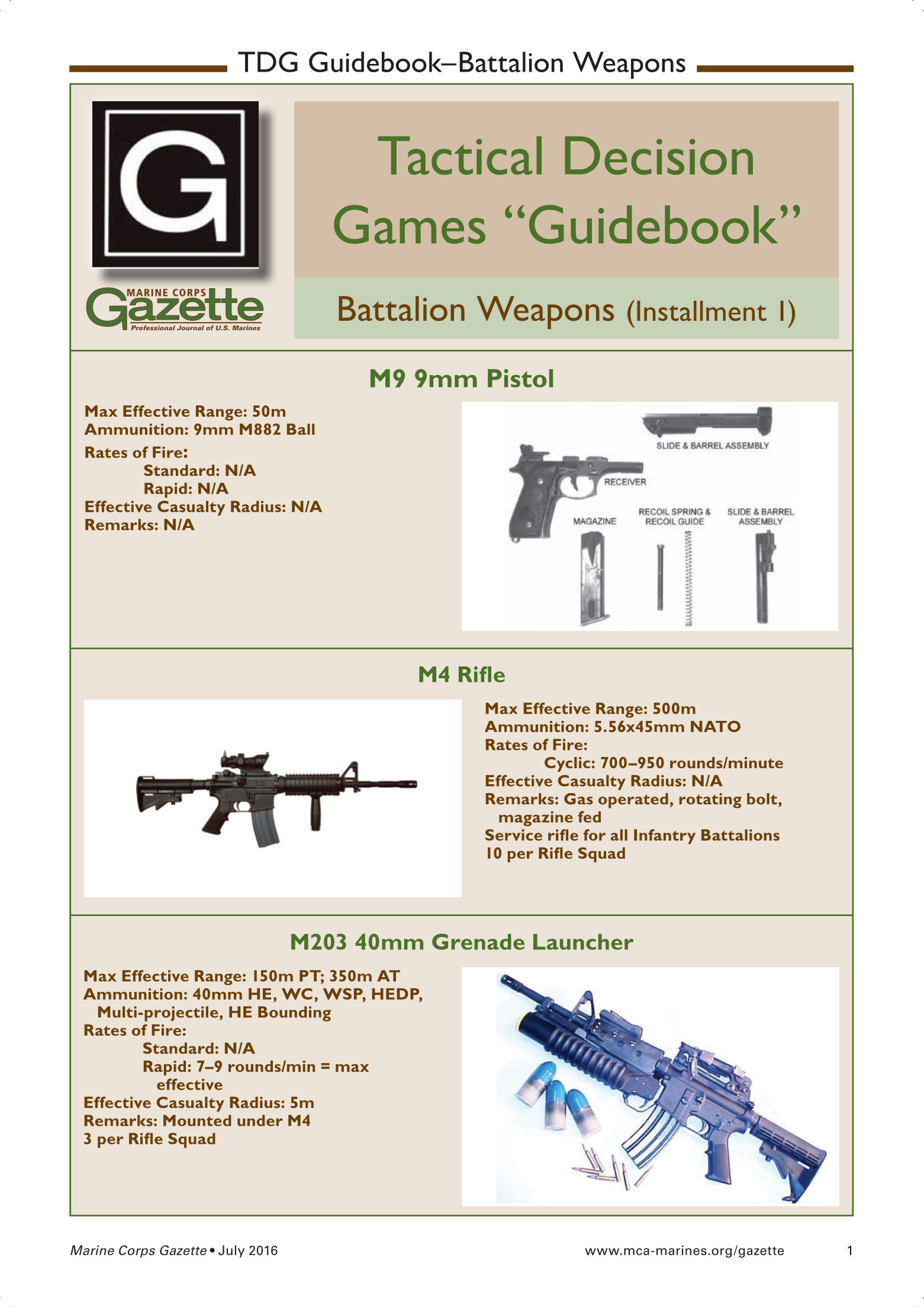

Training and education have often been looked upon synonymously, but they are very different concepts. Each complements the other, but each leads to distinctly different outcomes. Training is the acquisition of concrete skills that permits one to perform to standard. Therefore, training may be defined as an experience, discipline, or a regimen that causes people to acquire new predetermined behaviors.2 Training is the building-in of preset information and procedures-the technical aspect-oriented toward providing the mechanical wherewithal necessary to perform a particular task, the product of which is skill development and proficiency. An example of an outcome associated with training is the mechanical ability required to assemble and disassemble an M-16 rifle.

Education on the other hand, is that which is oriented toward developing leaders and decisionmakers. Education is the drawing out of students’ creative ability-the intangible human aspect-oriented toward providing the abstract ability to make decisions, the product of which is a creative mind. Where training deals with one correct way of performing a particular task, education addresses the internal nature of a problem to be solved, dealing with numerous possibilities rather than one correct answer. An example of an outcome associated with education is the creative judgment necessary for a leader to make a decision on the battlefield regarding the appropriate time or place to engage the enemy.

In practice it is not always easy to make a distinction between or to separate training from education since the ability to employ creative judgment requires technical expertise. MCU faculty should understand that training and education do not operate independently of one another. In fact training can best be viewed as a subset of education.3 Everything that is training is also education, but education also goes further. It attempts to get at the student’s creative aspect. Most often, the early stages of a Marine’s career should be weighted more heavily toward training since he or she more frequently will be engaged in operating a specific weapons system. Accordingly, the later stages of a Marine’s career should be dominated by education when that Marine is more likely to be in a leadership role.

Although the University should focus more heavily on education, it is clear that it is responsible for training as well. An appropriate balance must be maintained based on the nature of the desired outcome or impact on the student. Obviously a greater emphasis should be placed on training at The Basic School than at Command and Staff College. However, at both schools the requirement to address the intangible human ability related to combat decisionmaking, albeit at different levels, should be a priority.

Producing Combat Decisionmakers

During the 1930s, the leaders of the German Kriegsakademie (War College) absolutely believed that the capacity to make a decision in combat was the highest quality an officer could possess. The Germans called it “character,” and recruited their officers for its presence in their personalities and, thereafter, educated them to cultivate that capability.4 The requirement for character and decisiveness in combat is obvious. Developing the student’s character should be the preeminent purpose and the focus of effort for each member of the faculty at MCU.

The previous discussion of the differences between training and education demonstrates that a military decision is not just a mathematical computation. Decisionmaking requires both intuitive skill to recognize and analyze the essence of a given problem and the creative ability to devise a practical solution.5 There are several important yet somewhat intangible factors, identified in MCDP 1, that are both intuitive and creative in nature. When taken together the following factors form the essence of combat decisionmaking: (1) An understanding of the impact of uncertainty on the battlefield; (2) the ability to accept risk and act quickly; and (3) an understanding of the human dimension in war. Developing these abilities in students is no easy task. Combat decisionmaking should be viewed as a dynamic intellectual process which can in fact be created and shaped.

An understanding of the impact of uncertainty on the battlefield can be developed by ensuring that students do not always receive complete information. Situations should be created that by their nature are tentative and vague. Although this may result in student discomfort due to the lack of information, students should be forced to make decisions with incomplete information just as they would in combat. With incomplete information comes risk. The ability to accept risk can be developed by forcing students to make decisions and recognize the probable outcomes of their actions.

A commander should not only know how to arrive at a decision, but also when. It is better to render a partly faulty decision at the right time, than to ponder for hours over various changes in the situation and finally evolve a perfect decision-too late for execution.6 Since speed is a critical element of effective combat decisionmaking, the ability to apply quick recognition is a significant skill that should be practiced. To develop students’ ability to act quickly, situations have to be created that force students to convey their decisions quickly and in such a way that they can be understood and responded to effectively.

As stated in MCDP 1:

Because war is a clash between opposing human wills, the human dimension will always be central in war. The human dimension infuses war with its intangible moral factors and since war is an act of violence based on irreconcilable disagreement, it will invariably inflame and be shaped by human emotions. Unfortunately it is not feasible in an academic environment to realistically duplicate effects of danger, fear, exhaustion, and privation on students. Therefore, to develop in students an understanding of the human dimension in war, situations have to be created that emphasize historical examples of the intangible moral factors and emotions, as well as the human frailty and fallibility that shape combat.

Teaching Considerations

Schools like MCU develop new ideas and pioneer new methods. They encourage vision, imagination, and originality, as well as instilling a knowledge of the difference between a calculated risk and a gamble. In this environment, teachers and students alike are obliged to think about war and its conduct and to transmit their thoughts in articulate and comprehensive ways.7

Effective teaching for developing combat decisionmakers is different from that which most students have previously experienced. The majority of students have been educated through the use of “passive” teaching strategies. This technique is most often described as the traditional approach to teaching. It can be characterized by teachers delivering lectures and students passively listening. Basically, this is how most Marines have been taught in high school and college as well as during entry level training.8

Passive evaluations are short answer or multiple choice/fill-in-the-blank types of objective examinations. This is the standard military approach applied in training. The focus is content-based with a corresponding right answer or approved school solution. Implicit in this approach is the student’s dependence on the teacher to provide the information or content, preparation,9 and classic school solution. For example, in many Marine Corps academic environments, students have little choice about what they must do. Students must perform the prescribed task at a level acceptable to someone else, or fail.

The development of combat decisionmakers, however, should emphasize “active” teaching strategies. Active teaching strategies are problem centered rather than content centered. They encourage students to introduce past experiences into the process to reexamine that experience in light of new data or new problems. They suggest a climate of learning that is collaborative (teacher to student and student to student) as opposed to authoritative (one-way) oriented.lo These teaching strategies are characterized by active participation of students. This approach is more commonly applied to education. In the active approach the burden is on students to prepare, analyze, and present their views.11

Active learning evaluations are characterized by analyzing student performance in decisionmaking exercises under realistic conditions where there is incomplete information and realtime constraints. There may be more than one correct answer. In the active environment, the “school solution” is not as important as the process whereby students arrive at a given solution. The focus should be on the process of how to think, not only what to think.12

Establishing a Positive Learning Environment

The will to learn is an intrinsic motive, one that finds both its source and its reward in its own exercise. Studies have shown that the will to learn becomes a problem only under specialized circumstances where students are confined and a path is fixed.13 Establishing a learning environment at MCU conducive to developing students’ ability to think on their own is critically important.

The size of an instructional group is one significant determinant of the environment in which learning occurs. In some cases, positive teacher-to-student interaction is more readily attained with small groups, and in some cases with large. Possibly even more important than teacher-to-student interaction is a learning environment in which significant student-to-student interaction can be established to enhance learning.

MCU uses various sized instructional groups and a wide variety of educational methodologies to facilitate learning. These include lectures that might contain as many as 200 students, and small discussion or practical exercise groups that might contain as few as 5 and as many as 30 students. The obvious difference in the size of instructional groups can be seen in the difference between the large lecture format and the small group format. The opportunity for student-to-student and teacher-to-student interaction in large instructional groups of 100 or more students is significantly less than in smaller instructional groups of 10 to 15 students. For some students the large group may frequently be more comfortable since the requirement and opportunity to participate is far less than in a small group setting. In simple terms, there just is no place to hide in a smaller group. Additionally, in a small group environment students are more compelled to become actively involved in their own education, rather than in simply absorbing information.

Teaching Strategies for Developing Combat Decisionmakers

Confucius is attributed with having said, “I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand.”14 This is a well-respected assertion often repeated in American culture-students learn by doing. There is appropriate basis in fact if this assertion is properly explained: ( 1) Students learn to do better if they make an attempt; (2) evaluate that effort; and (3) modify their consequent efforts in ways that increase their effectiveness. ” This approach can most aptly be described as getting students involved in the learning process.

Teaching students to make decisions can be far more effective when students are required to evaluate their own performance. Using this approach, students are presented with realistic problems requiring a decision. Having been given opportunities to make decisions, they then should analyze the process by which they reached a particular decision. This may include teacher development of feedback for a specific decision, followed by a student response, and subsequent discussion of teacher and student perceptions on how the decision was formulated. This process culminates in understanding how the initial decision was made.lb Teachers can most effectively develop student ability to make decisions by fostering an academic environment that provides guidance to students on how to monitor and improve their own decisionmaking behavior. This guidance should come in the form of practice with immediate feedback and discussion to facilitate improvement.

What specifically can faculty do to help students monitor and improve their ability to make decisions? While much remains to be learned about how to influence combat decisionmaking ability, one effective teaching strategy involves allowing students to discover effective decisions through trial and error. “Discovery” can occur through direct experience, in which students reach appropriate decisions by simply trying to do it. It can also occur through vicarious experience, in which students develop their understanding of combat decisionmaking by thinking about a fictional case study presented by the teacher. Last, discovery can occur by analyzing historical examples in which students examine real events. In any of these cases, guidance by asking effective leading questions has been proven to greatly decrease the time required to discover and fully absorb decisionmaking skills. Of course after skills have been discovered, students should receive feedback as to the probable outcome of their decision in comparison to others they could have discovered.17

For discovery to be an effective teaching strategy, faculty should use real life feedback as much as possible. What would the real consequences have been, good or bad, of a particular decision? How do students react to these consequences? For example, teachers should allow students to observe, albeit through artificial means (map exercises, terrain models, or computer simulations), the results of their actions. In other words, students should be able to visualize the results of a particular decision: what it would have looked like; what the likely outcomes would have been-both positive and negative.

Additionally, for discovery to be an effective teaching strategy, faculty should allow students to make mistakes. Students should always be given another opportunity to act if their initial response is inappropriate. Continuous opportunities for active practice will enhance success. Teachers should provide feedback that suggests, rather than dictates to students. Although this feedback should inform students of the correctness or incorrectness of their thinking, it should never point to the school solution. This is not to say that providing a recommended solution is inappropriate; simply that, if provided, a school solution should be presented as a “possible solution,” one among many possible solutions not necessarily as the best solution. Feedback from teachers in this regard should provide suggestions that help students to discover a better way by emphasizing that which they already understand.

Another effective teaching strategy involves the use of simulations. A “simulation” replicates as much as possible the requirements and conditions that will be imposed on students in real combat situations. One familiar example of a simulation is the “tactical decision game.” Tactical decision games can be used to simulate problems not just at the tactical level but at the operational and strategic levels as well. Depending on the level which is addressed in the simulation, students are provided with an appropriate tentative intelligence situation, provided a fragmentary order or appropriate guidance, and asked, “What would you do?” Students provide an initial response and the teacher provides an intelligence update that requires them to further analyze a developing situation. Students are once again asked, “What would you do?” and again students should provide a response. This can continue until the teacher is comfortable with the individual student’s thought processes. If students make ineffective decisions they will get immediate feedback from the teacher including the probable results of the decision. Using this approach, the individual thought processes whereby students reached a decision can be examined in depth. This approach can be used in any type of simulation from simple tactical level decisionmaking games to very elaborate strategic level war games. In any case, the format is not as important as the teaching strategy. The strategy employed in simulations allows students to get immediate feedback on the likely results of their actions that allows them to closely examine their thinking.

“Cooperative learning” is yet another effective teaching strategy that can be used to influence the development of effective combat decisionmakers. This approach is based on the fact that each student brings to a particular group a unique set of experiences and knowledge. The success of this strategy depends on creating a learning environment in which significant interaction occurs between students. The opportunity to work together in different groups exposes students to a wide variety of individual knowledge and experience. This interaction provides: ( 1 ) Additional feedback for students; (2) opportunities for students to observe how their contemporaries draw conclusions and reach solutions; and (3) opportunities for students to explore and seek out alternative approaches to combat decisionmaking through the close examination of other student perspectives on the same problem. Each student con tributes to, and draws from, the experience of others through student-to-student interchanges. The group can provide a highly stimulating environment where each participant realizes the potential of a higher level of performance.18

The Nature of the Teacher-Student Relationship

There are many factors that contribute to successful teaching. Many of these have already been addressed. Yet another important factor affecting teaching success is the relationship established between the teacher and the student. The quality of this relationship works hand in hand with the learning environment to shape the attitude students develop toward the University’s educational philosophy and, in large part, determines students’ motivation to learn.

The relationship between student and teacher should promote trust and shared responsibility and foster an equal partnership between the student and the school. This relationship is very different from the traditional concept of the dominant teacher and dependent learner. It features reciprocity between the teacher and student. In other words, the teacher and student must be equally active.19 For example, students should not be allowed to withdraw, to be passive, untalkative, or to expect the teacher to do all the work. Conversely, teachers must recognize that students, under the proper conditions, can be highly motivated and capable of directing their own learning if given the opportunity.

The teacher’s prime responsibility may well be to reduce his importance to help learners arrive at their own freedom to learn.20 For example, by simply avoiding the desire to provide students with immediate solutions or feedback, teachers can encourage students to further pursue their own experiences and knowledge-thereby allowing them to further develop their own ability to learn and make decisions. This involves empowering or permitting students to make responsible choices about the direction of their learning and to assume responsibility for those choices: the mistaken as well as the correct choices. To empower students is to enable those who would have otherwise been silent to speak.21

The Development of the Faculty in the Field of Teaching

It is incumbent upon MCU to develop in its faculty the abilities its members need to become effective teachers. Effective faculty are those who are well versed in their roles, as facilitators, as mentors, and as coaches to develop students who will be effective combat decisionmakers. If faculty are to become more successful in the field of teaching, a workable approach to faculty development should be instituted.

Faculty members need some release from being teachers and some stimulation which derives from being learners. Deep down, most people know that they do not know very much in the totality of life; most still seek significant learnings.22 It is important that faculty at MCU understand that they are all students and that they continue to learn each day. Some of this energy should be expended in helping faculty to fulfill their most important responsibility: teaching the future leadership of the Marine Corps.

Notes

1. Richardson, General W.R. (1984, p.26). Kermit Roosevelt Lecture: Officer Training and Education. Military Review. No. 10, October.

2. Laird, D. (1985, p.ll). Approaches to Training and Development. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

3. Nadler (1982, p.7). Designing Training Programs: The Critical Events Model. Reading MA: Addison-Wesley.

4. Wedemeyer, Capt A.C. (1938, p.5). G-2 Report, Subject: German General Staff School. Berlin, Germany: Report 15, 999, July 11, 1938. Library of Congress.

5. United States Marine Corps. (1989). Fleet Marine Force Manual 1 (FMFM-1 (1989, p.69). Warfighting. Washington. D.C.

6. Wedemeyer, Capt A.C. (1938, p.l5). G-2 Report, Subject: German General Staff School. Berlin, Germany: Report 15, 999, July 11, 1938. Library of Congress.

7. Richardson, General W.R. (1984, p. 26).

8. U.S. House of Representatives. (1989, p.158). Committee on Armed Services, Report of the Panel on Military Education. Washington, D.C.: 101st Congress, Ist session, Apr. 11-21, Committee print, Number 4.

9. Whitley, MA. Jr. (1989, p.6). Critical Requirements for Army War College Faculty Instructors. Military Studies Program Paper, Carlisle, PA: U.S. Army War College, 16 April.

10. Laird, D. (1985, p.125).

11. Eble, K.E. (1990, p.4). The Craft of Teaching. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

12. Richardson, General W.R. (1984, p.33).

13. Bruner,J.S. (1966, p.127). Toward a Theory of Instruction. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

14. Sheets, T.E. (1992, p.1). Training and Educating Marine Corps Officers for the Future. U.S. Army War College Military Studies Program Paper: Carlisle, PA.

15. Patton B.R., Giffin, K., and Patton, E.N. (1989, p.l57). Decision Making Group Interaction. New York: Harper and Row.

16. Leshin, C.B., Pollock, J., and Reigeluth. (1992, p.231). Instructional Design Strategies and Tactics. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

17. Leshin, C.B., Pollock, J., and Reigeluth. (1992, p.234).

18. Patton, B.R. Giffin, K., and Patton, E.N. (1989, p. 158).

19. Nadler, L. (1982, p. 150).

20. Eble, K.E. (1990 p.9).

21. Simon, R. (1987, p.374). Empowerment as a Pedagogy of Possibility. Language Arts. No. 64.

22. Ducharme, E.R. (1981, p.33). Faculty Development in Schools, Colleges, and Departments of Education. Journal of Teacher Education, Number 5, Sept-Oct.