By Gen Charles C Krulak

It is my intent in preparing the force that we account for . . . [the demands of the 21 st century] by creating Marines and their leaders who have superb tactical judgement and are capable of rapid decisionmaking under physical and emotional duress….

-Commandant’s Planning Guidance

Our world is becoming increasingly chaotic. Operations such as those in Bosnia, Haiti, and Somalia-where the unique challenges of military operations other than war have been combined with the disparate challenges of midintensity conflict-are becoming commonplace. The tragic experience of U.S. forces in Mogadishu during Operation RESTORE HOPE illustrates well the volatile nature of these contemporary operations.

The Strategic Corporals . . . and Their Leaders

Marines involved in these amorphous conflicts will be confronted by the entire spectrum of tactical challenges in the span of a few hours and, potentially, within the space of three contiguous city blocks. Thus, we refer to this phenomenon as the “three block war.” Success or failure will rest, increasingly, with the individual Marine on the ground-and with his or her ability to make the right decision, at the right time, while under extreme duress. Without direct supervision, young Marines will be required to make rapid, well-reasoned, independent decisions while facing a bewildering array of challenges and threats. These decisions will be subject to the harsh scrutiny of both the media and the court of public opinion. In many cases, the individual Marine will be the most conspicuous symbol of American foreign policy. His or her actions may not only influence the immediate tactical situation, but have operational and strategic implications as well. If we accept the maxim “battles are won and lost [first] in the mind of the commanders,” we can safely assume that the three block war, may very well be won or lost in the minds of our “strategic corporals.”

So the natural question becomes, “How do we develop our strategic corporals’ abilities to make sound and timely decisions in the heat of the three block war?” How do we prepare them to deal decisively with the challenges they are destined to confront on the complex, high-stakes, asymmetrical battlefield of the 21 st century? Further, the chaotic conditions of the next century promise to increasingly tax the individual decisionmaking skills of both commanders and staff officers at all levels. The influx of information into our combat operations and fire support coordination centers is growing at a rate faster than our ability to “process” it. Thus far, advances in information technology have increased, not diminished, the burden on our officers to make the “hard calls.” Marines must rapidly distinguish between information that is useful in making decisions, and that which is not pertinent. Often, they must avoid the natural temptation to delay their decision until more information makes the situation clearer or risk losing the initiative. In all likelihood, once military action is underway, more information will simply further cloud the picture. Our leaders must be able to “feel” the battlefield tempo, discern patterns among the chaos, and make decisions in seconds much like a Wall Street investment trader, but with life threatening consequences. In short, we must ask ourselves, “From the strategic corporal to the Marine expeditionary force (MEF) commander, how do we ensure that each and every Marine has the decisionmaking ability needed to execute his or her responsibilities?”

The Essence of Decisionmaking

In answering this question, we must first gain a fundamental understanding of decisionmaking itself. Decisionmaking is the foremost human factor, indeed unique contribution, involved in warfare. In effect, it is the means for implementing the human will. As long as wars result from two opposing human wills, they will be emotional and chaotic in nature. Technological or scientific solutions alone will not be adequate to resolve these conflicts; nor will they be able to lift “the fog of war.”

Generally, we know that there are two primary models for human decisionmaking-the analytical model and the intuitive, or recognitional, model. Military leaders at all levels are familiar with the analytical model because it is the one historically used in our formal schools. In this model, Marines prepare estimates of the situation that eventually evolve into potential courses of action. Analytical decisionmaking uses a scientific, quantitative approach, and to be effective, it depends on a relatively high level of situational certainty and accuracy. The greater the degree of situational certainty and awareness, the more effective analytical decisionmaking becomes. Unfortunately, the analytical model does not lend itself well to military applications once the enemy is engaged. At that point, military situations most often become very ambiguous, and the leader cannot afford to wait for detailed, quantitative data without risking the initiative. Analytical decisionmaking offers distinct advantages when the situation allows an indefinite amount of time for analysis, such as during prehostility contingency planning, but it rapidly diminishes in usefulness once “you cross the line of departure.”

While analytical decisionmaking is based on a comparison of quantitative options, recognitional decisionmaking depends on a qualitative assessment of the situation based on the decider’s judgment and experience. It does not look for the ideal solution; instead, it seeks the first solution that will work. Research by noted psychologist Dr. Gary Klein indicates that most people use the intuitive model of decisionmaking over 90 percent of the time. Ironically, until recently our formal schools have focused almost exclusively on training Marines in the analytical model. This began to change, however, with a growing acceptance of the ideas presented by the late Col John R. Boyd, USAF(Ret). Boyd demonstrated that a person in the midst of conflict continuously moves through a recognitional decision pattern that he termed the “Observe-Orient-Decide-Act (OODA) Loop.” He pointed out that the leader who moves through this OODA cycle the quickest gains a potentially decisive advantage in the conflict by disrupting his enemy’s ability to respond and react. In short, the leader who consistently makes the faster decisions can interfere with his opponent’s decisionmaking process and effectively degrade his ability to inflict his will and continue the struggle. Col Boyd’s ideas, entirely consistent with the Marine Corps’ maneuver warfare philosophy, were incorporated into our doctrine in 1989.

As Col Boyd recognized, the chief advantage of intuitive decisionmaking in military operations is its speed. Numerous military historians and sociologists, including such notables as John Keegan and S.L.A. Marshall, have pointed out that the normal tendency for inexperienced leaders under extremis conditions is to wait for as much information as possible before making a decision. Of course, the longer the decision is delayed, the more opportunities are missed. Initiative can be forfeited to the enemy. For this reason, Sun Tzu noted that, “Speed is the essence of war,” and Patton observed, “A good plan executed now is better than a perfect plan executed next week.” History has repeatedly demonstrated that battles have been lost more often by a leader’s failure to make a decision than by his making a poor one.

Napoleon believed that the intuitive ability to rapidly assess the situation on the battlefield and make a sound decision was the most important quality a commander could possess. He referred to this intuition as coup d’oeil, or “the strike of the eye,” and thought that it was a gift of nature. More recently, however, practitioners of the military art have come to believe that while heredity and personality may well have an impact on an individual’s intuitive skills, these skills can also be cultivated and developed. Prior to and during World War II, the Japanese called this skill, ishin denshin, or the “sixth sense,” and they observed that it began to appear after months of intense repetitive training in a cohesive unit. During the same time period, the Germans referred to the capacity to make rapid, intuitive decisions in combat as “character.” They attempted to first identify innate intuition during their recruiting processes, and then cultivate the skill by forcing their officers to repeatedly make tactical decisions under stressful situations throughout their professional schooling. While some might point out that both the Germans and Japanese were on the losing end of World War II, we might be wiser to ask how they were able to achieve such great military successes given their relative size and resource limitations. Napoleon may be correct if he meant that intuition cannot be taught in the traditional sense, but both the Germans and the Japanese were successful in assuming that-through repetition-it could be learned.

How Do We Cultivate Napoleon’s Coup D’Oeil? Character. If we accept that intuitive combat decisionmaking skill will be exceedingly important for all Marines in the 21st century, we must seek to cultivate that ability. Our first step, however, must be to identify an important prerequisite for sound decisionmaking-sound character. As often as not, the really tough issues confronting Marines in the three block war will be ethical/moral quandaries, and they must have the wherewithal to handle them appropriately. We cannot anticipate and train Marines for each situation they may face. All Marines must, therefore, possess a moral consistency to serve as their compass. Making the right ethical decisions must be a thing of habit. This is why we created the Transformation Process where we recruit bold, capable, and intelligent young men and women of character and recast them in the white hot crucible of recruit training. We immerse them in the highest ideals of American society-the time honored values of our Corps-honor, courage, and commitment. We place these values on them in a framework of high institutional standards to which they are held strictly accountable. We further foster the acceptance of these values through the unit cohesion and sustainment phases. The common thread throughout Transformation is an emphasis on the growth of integrity, courage, initiative, decisiveness, mental agility, and personal accountability-the basic skills needed to make timely, accurate, and ethical decisions in the heat of combat.

Repetitive Skills Training. If we know that the effectiveness of intuitive decisionmaking is dependent upon experience, we must seek ways to give our Marines that experience. We should recognize decisionmaking as a vitally important combat skill and promote its development throughout our training curriculum, both in our formal schools’ curriculums and in our local unit training programs. We must face the paradox that our least experienced leaders, those with the least skill in decisionmaking, will face the most demanding decisions on the battlefield. Just as we expect a Marine to employ his weapon under combat duress, we must likewise demand that he employ his mind. Marines need to be comfortable with using their intuition under highly stressful circumstances. In short, we must make intuitive decisionmaking an instinct, and this can only be accomplished through repetition. Training programs and curriculums should routinely make our Marines decide a course of action under cold, wet, noisy conditions while they are tired and hungry and as an instructor continually asks them “what are you going to do now, Marine?”

Unit commanders must scrutinize their training programs to ensure that operational exercises are geared to challenge the intuitive decisionmaking processes of subordinate leaders at every level in their command. Training must account for the role of uncertainty in decisionmaking. We should literally bombard them with information and get them used to making decisions under varied circumstances without complete information and with contradicting or false information. Similarly, we must continually review and revise our formal schools’ curriculums-from the Schools of Infantry to the Marine Air-Ground Task Force Staff Training Program and up to and including the Marine Corps War College-to dramatically increase the number of times we force each Marine to make decisions.

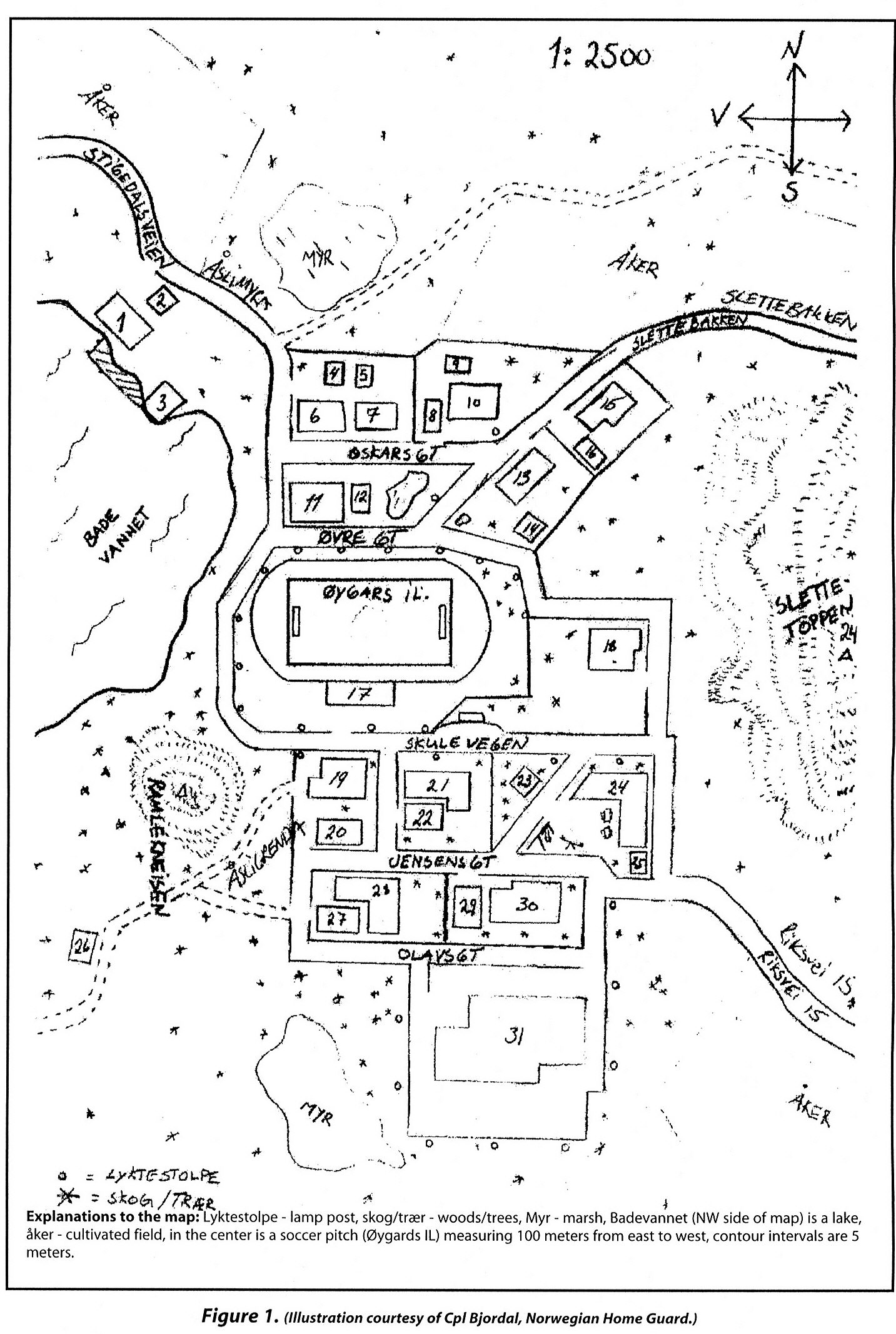

Our Warfighting Lab has led the way in developing practical tools to support this type of instruction with the computer assisted training simulation known as the Combat Decisionmaking Range (CDR). The CDR puts the squad leader square in the middle of the three block war and requires him to make decisions across the spectrum of conflict, from humanitarian relief to midintensity firefights, with the media watching. During a single 30- to 45-minute CDR training scenario, a Marine squad leader must make 15 to 30 urgent, life or death decisions while land navigating and communicating both up and down the chain of command. The results of experimentation with the CDR indicate that we are on the right course. Squad leaders who routinely exercise in the CDR gain confidence in their intuitive abilities and make sound decisions more rapidly.

Initiatives similar to the CDR should be pursued in all of our professional schools and in our operational units. At each level, from young, aspiring noncommissioned officers to our MEF commanders, our training should be geared to putting the Marine in the appropriate stressful environment for his or her grade, and forcing them to make timely decisions. Initially, it is important that the correctness of the decision not be an issue. The “right” decision is any decision as long as it is timely. After all, in combat situations there are rarely any right or wrong answers. As the conditioning proceeds, appropriate postexercise critiques and debriefs will begin to identify in the participant’s mind the credibility of various decisions (or “solutions”) in relative terms. Through this process, they will begin to develop an intellectual framework for making time-critical decisions in their billet.

Self-Study. A personal commitment must be made by each Marine to focus on developing his or her own decisionmaking abilities. This means self-study; but simply reading history is not enough. We need to read it with an eye toward examining the relevant decisionmaking processes that took place during the particular event. Why did the commander make this decision? What information did he have when he made it? What information did he not have? Was it timely? What subsequent decisions did he make and why? What were the resuits? Personal study of history and the military art in this manner promotes an ability to recognize patterns and later, to exploit them. While it is no substitute for personal experience, the dedicated study of conflict and warfare complements tactical decision games, simulations, and exercises in establishing a mental framework for making time-sensitive decisions.

Command Climate. While the most realistic training in the world may never be able to replicate the stresses associated with making decisions in combat, we must actively pursue means of conditioning a willingness among our Marines to make those decisions. We should literally inculcate a “culture” of intuitive decisionmaking throughout the Corps. To do so requires that commanders at all levels create within their units an atmosphere that encourages, not inhibits, their subordinates to make decisions. Subordinates must be assured that their leaders will back them up when they make a poor tactical decision. Debriefs and critiques must challenge the subordinate’s rationale, but not threaten his or her pride or dignity. This, of course, is not possible in a command where micromanagement or a “zero-defects mentality” is prevalent.

Continuing to March

The Marine Corps Combat Development Command will dedicate itself to identifying, developing, and cultivating appropriate intuitive combat decisionmaking skills at all levels. Our Warfighting Lab will continue to take the lead with initiatives such as the Traders Games with the New York Mercantile Exchange, concepts and ideas exchanges with the New York City Fire Department, and the Dynamic Decisionmaking Wargame involving traders, firefighters, police officers, air traffic controllers, and other professionals. The Lab should eventually expand their experimentation efforts in this area beyond the training realm. They should seek to answer such questions as: Can certain personality types develop intuitive skills more readily than others? Is there a means for testing this? Do different billets, assignments, and military occupational specialties require different types of intuition? Should our manpower processes-recruiting, promotion, billet assignment, command selection, etc.-consider these factors? Answering questions such as these will help us field leaders at all levels with the decisionmaking skills they will need to fight and win the three block war.

Summary

Our warfighting philosophy, both now and with the growth of operational maneuver from the sea, is one of maneuver. Maneuver doctrine, to be successful, demands high tempo in order to retain the initiative and impact the enemy’s will to fight. Without leaders who can make timely decisions under extreme duress, this doctrine simply cannot succeed. These leaders cannot rely on the traditional, analytical approach to decisionmaking. Advances in information technology will never clear Clausewitz’s “fog of war” to the point where the analytical model is timely enough to guarantee victory. Marine Corps leaders, therefore, need to develop confidence in their own intuition-an intuition rooted firmly in solid character. We must actively seek out means for cultivating intuitive decisionmaking skills among our leaders at all levels from the strategic corporal to the MEF commander. Since these intuitive skills result from experience, we must include repetitive decisionmaking drills and exercises in all of our formal schools’ curriculums and in the training programs of our operational units. Finally, our commanders must foster a climate within their units that is supportive of intuitive skill development. Doing these things will cultivate coup d’oeil and guarantee our success on the 21st century battlefield.