by Maj A. C. Bevilacqua, USMC(Ret)

The burgeoning interest displayed by Marine officers and NCOs in the armed forces of the Soviet Union gives evidence of the continuing high standards of professionalism long credited to Marine leaders. A constant awareness and understanding of the global military environment being one of the salient features of the profession of arms, tactical skills can only be enhanced by the knowledge thus acquired.

Beyond the study of the nature and conduct of Soviet combat operations, there exists the greater opportunity to analyze and appreciate these activities through an examination of the doctrinal principles upon which they are based. Indeed, such examination is a basic necessity inasmuch as tactical doctrine provides the military analyst the key to understanding the reasons behind the Soviet force organization, equipment, employment, and the practical battlefield aspects of Soviet offensive and defensive combat.

In discussing these doctrinal principles, contemporary Soviet military literature stresses their evolutionary nature-a continual change due to what the Soviets see as “the revolution in military affairs” brought about by high technology weaponry, increased mobility, and nuclear and chemical weapons. Thus, Soviet tactical doctrine may be seen to incorporate a certain flexibility. It is amended as necessary to reflect current conditions. What is defined as doctrine today is a mixture of uniquely Russian fundamentals blended with a moderate fluidity of concept stemming from the potential impact of weapons of mass destruction. The battlefield manifestation of this thinking is a strong emphasis on high mobility actions which nevertheless retain noticeable aspects of the traditional Russian preoccupation with mass.

The formalized principles of tactical doctrine which have evolved from this thinking form the basis of Soviet military planning and the conduct of combat at all levels: strategic, operational, and tactical. Indeed, these three levels of combat activity are in themselves unique aspects of Soviet doctrine, which considers strategic actions as occurring at the global, national, and theater levels, while operational actions are conducted by fronts and armies, with divisions and lesser formations concerned with the prosecution of tactical actions. Regardless of the level, the doctrinal principles apply. At present, these are seven such principles:

* Mobility and high rates of combat operations

* Concentration of main efforts and creation of superiority in forces and means over the enemy at the decisive time and place

* Surprise and security

* Combat activeness

* Preservation of the combat effectivess of friendly forces

* Conformity of the goal

* Coordination

Casual examination of these principles may suggest them to be mere rephrasings of the classic principles of war. However, Soviet views of their meaning and application, especially in a nuclear or chemical environment, are worthy of investigation. Both individually and collectively, they reveal significant facets of Soviet military philosophy and provide insight into how Soviet forces will be employed on the battlefield.

Mobility and High Rates of Combat Operations

This principle is directed at the dual requirements of rapid movement in the execution of combat missions and the maintenance of continuous, sustained action. The maneuverability and unrelenting rapid movement of maneuver forces, supporting arms, and logistics elements are seen as indispensable in the conduct of fast-paced shock actions that seek to preclude the opponent from assuming a position of preparedness and constantly force him to fight on unfavorable terms. Speed in the execution of all combat tasks is of the essence, as is the ability to shift rapidly from one task to another. The enemy must be forced to assume the defensive while simultaneously being denied the opportunity to form a cohesive and effective defensive posture.

Through the continuous application of shifting, moving forces and equally continuous application of combat power, the Soviets seek to retain tactical initiative. In practice, this means that the opponent must be kept under constant pressure, “crowded,” prevented from establishing an effective defense or assuming the offensive, and absolutely denied the opportunity to exercise combat initiative. The opposing commander must be forced to accept battle on Soviet terms, and to this end combat actions are envisioned as continuing without pause, with no slackening due to conditions of weather, visibility, or terrain.

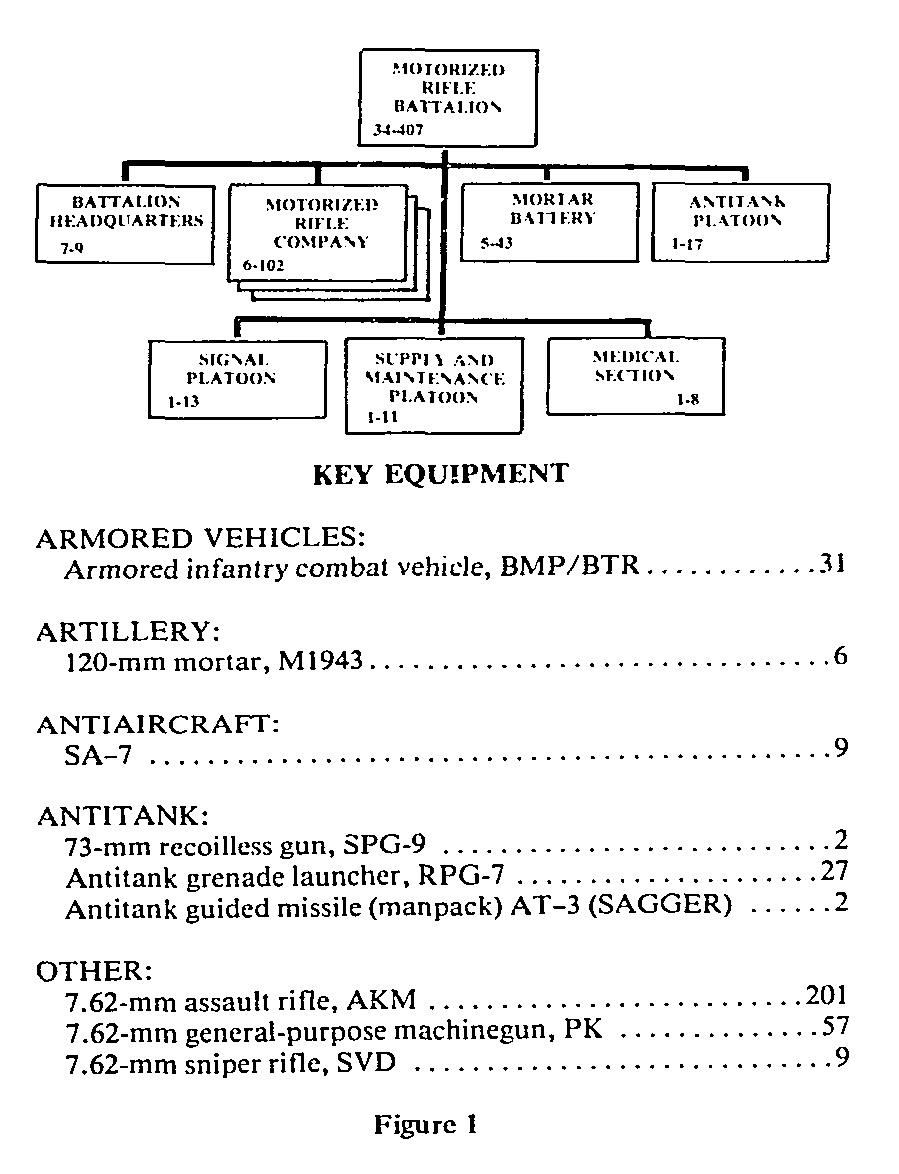

The material evidence of Soviet adherence to this principle may be seen in the proliferation of general and special purpose vehicles found in Soviet forces. Tanks, infantry combat vehicles, engineer combat vehicles, self-propelled artillery, and air defense weapons all attest to the ceaseless Soviet effort to provide the material means of observing the principle. Special purpose units, such as pipeline and lines of communication troops, give additional evidence of the degree to which the Soviets have organized their forces for the conduct of mobile, high-intensity operations.

On the battlefield, offensive tactics that have evolved from this principle are the meeting engagement and the hasty attack, both of which are predicated upon assault conducted directly from the line of march. During the conduct of the defense, the requirement for rapid maneuver of antitank and counterattack forces springs directly from the principle. Observation of the principle is regarded as critical in a nuclear environment, allowing maximum exploitation of Soviet nuclear strikes while avoiding the effects of the opponent’s nuclear weapons.

Is the theory represented by the principle a new development in warfare? Of course not. Such modern commanders as Rommel, Patton, and “Hurrying Heinz” Guderian appreciated it fully and practiced it constantly. In our own military history, Stonewall Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862 was a classic example of its application. Confederate A.P. Hill would have felt right at home with this principle in his driving forced march from Harper’s Ferry, which brought his light division to the battlefield at Sharpsburg (Antietam) in time to swing directly into the attack and save the day for Lee’s army.

The unique aspects of Soviet pursuit of this principle lie in the structuring and equipping of forces, coupled with the adoption of specific combat tactics to achieve it. The manner in which the Soviet force is organized and equipped, and the manner in which it is employed serve as interrelated elements in utilizing the principle as a major means of accruing tactical initiative to the Soviet commander while denying it to his opponent. Without a means of negating Soviet mobile capabilities and without a like degree of mobility in his own force, the opposing commander will be relegated to a role of merely responding to Soviet combat initiatives planned to force him into an inferior tactical position.

Concentration of Main Efforts and Creation of Superiority in Forces and Means Over the Enemy at the Decisive Time and Place

Seemingly wordy and intricate, this principle quite simply emphasizes the Soviet perception of the absolute necessity for local superiority in the main effort during both offensive and defensive combat. It is a premier means by which the Soviets seek to attain the desired ratio of forces at the critical point and serves as a necessary coefficient of the principle of mobility. Not just mass, but mass at the time and place chosen by the Soviet commander, is its salient characteristic.

Essential features of the principle‘s application lie in the concentration of maneuver elements from relatively dispersed locations to critical poinls of attack for short periods of time and the increasing tendency toward the performance of combat tasks by combined arms units. This rapid shifting of mobility and firepower requires a high degree of coordination between all participating units in order to achieve superiority of forces in critical areas for the time needed to attain tactical dominance, yet not for so long a time as to present targets for the nuclear weapons of the opponent.

In addition, this principle may be seen as the basis for many of the Soviet requirements for the employment of artillery, inasmuch as concentration implies not only maneuver elements, but also the concentration of supporting fires as well. The great emphasis placed upon establishing prescribed ratios of destructive and suppressive fires springs directly from the principle, since it is precisely such concentration of fires that is expected to create favorable conditions for the movement of tank and motorized rifle units. The rapid introduction of large numbers of self-propelled artillery pieces, the beginnings of a decentralized fire support coordination system, and increased artillery communications all give evidence of the Soviet desire to exploit more fully the inherent capability of artillery to deliver concentrated fires while the firing units themselves remain dispersed.

Putting this principle into practice has not been without problems for Soviet military planners. The gathering of widely dispersed maneuver units along relatively narrow frontages for short periods of time has created requirements for command and control communications far above those previously needed by Soviet forces, which in the past have been characterized by highly centralized control. These added communications have perforce noticeably increased the opportunity for SIGINT/ECM/ESM operations by the opponent and created added ECCM problems for the Soviets.

Beyond these considerations, there are historical and philosophical problems involved. The very need to conduct what is basically a fluid action that relies greatly upon the initiative of junior commanders is itself at variance with traditionally Soviet military practice of structured operations planned and controlled in great detail, indeed, the very junior commanders who are so essential to the successful conduct of fluid operations are themselves products of a rigidly structured socio-political system that is predicated upon direction from the top down and thus discourages individual initiative. One practical result of this condition, one which has been noted in recent Soviet military writings, has been the difficulty encountered in effectively coordinating supporting arms below division level.

What has emerged from this clash of theory with reality is a form of combat that, while seemingly fluid in nature, may be discerned as an attempt to structure and “choreograph” operations requiring the coordination and interplay of widely separated units. Whether it will succeed in the face of a determined opponent who aggressively interferes with its conduct is yet to be seen.

Surprise and Security

The Soviets consider security to be an integral element of surprise and view both as necessary complements of the first two principles. At the strategic level, surprise is considered as containing political and psychological elements as well as military action. Operationally and tactically, the principle is directed at the initiation of combat action at unexpected times and places in order to realize a decisive advantage. In common with Western theories of surprise and deception, it is not considered necessary that the opponent be taken completely by surprise, only that he remain unaware until it is too late to take effective counteraction.

In furtherance of surprise, the Soviets undertake a wide variety of operations and communications security measures as a means of shielding the locations and activities of forces. Each deception measure is complemented by appropriate denial measures. Engineer, tank, and motorized rifle elements are specifically designated in combat orders for the performance of bogus activity in the conduct of deception measures, while widespread counterreconnaissance activity seeks to shield the Soviet force from the intelligence services of the opponent. Further battlefield measures contributing to observation of the principle may be seen in the widely conducted and strictly enforced individual and unit camouflage measures undertaken by troops of all arms. The primary goal of such activities is to deny the opponent’s intelligence machinery the informational raw material it requires to perform a valid analysis of the Soviet force.

In addition to tactical actions undertaken to accomplish the principle, Soviet equipment, especially combat vehicles, incorporates design features which make direct contributions to the objective. Since planned night actions and actions during periods of severe weather and reduced visibility are seen as desirable, not as inconveniences, it is not surprising to note active or passive night vision devices and cold weather operating features as integral components of vehicle design. The simple, inexpensive smoke generating mechanism on all Soviet tanks gives added evidence of the manner in which equipment contributes to the execution of doctrine.

Here once again, the analyst is able to note clear emphasis placed upon combat initiative by the Soviets. Soviet formations must not only move quickly and effectively in the application of combat power in critical areas, but they must also strive to create conditions of the unexpected to which the opponent is unable to react in a timely manner. In this creation of combat by unexpected means, and at unexpected times and places, the close interworking of Soviet doctrinal principles is clearly discerned.

Combat Activeness

Characterized by some Western analysts as tactical boldness or command decisiveness, this principle is closely akin to its predecessors, and as is the case with each principle, is meant to be a complementary part of the overall doctrinal whole. It furnishes particular emphasis of the importance placed by the Soviets upon setting the tempo of battle through seizure of the initiative, thereby dictating the terms of combat. The primary concern of the principle is directed at finding ways and means of sustaining high mobility operations and maintaining or regaining the offensive at all levels.

In this sense, the principle may be observed in defensive combat as well. Close examination of the conduct of the defense by Soviet forces reveals aggressive counterattacks to be the ultimate element of the defensive plan. While the opponent’s attack is diffused and slowed by defenses in depth, the bulk of Soviet tank forces are almost invariable held in reserve for the express purpose of counterattack and resumption of the offensive. From the standpoint of the opponent, therefore, location and neutralization of Soviet tank reserves is of paramount importance if the defender is to be denied the opportunity to restore the situation and resume offensive action.

The salient philosophical conclusion drawn from the analysis of this principle is the Soviet unwillingness to be forced into a role of response. Constant and unceasing combat activity by Soviet forces must serve as yet another means by which the opponent is to be kept continually off balance and forced to fight on unfavorable terms at times and places not of his own choosing.

Here again, however, in executing the principle Soviet forces fall victim to the reality of the rigid nature of the communist state. Combat activeness, essentially an extemporaneous undertaking, becomes the subject of direction from above and the dictatorship of schedules, timetables, and “norms.” As long as the opponent is accommodating in allowing Soviet exercise of the initiative and the development of events in accordance with the Soviet plan, the observation of the principle is generally ensured. However, the exercise of combat activeness when confronted by combat variables and unexpected situations is markedly less than certain.

Preservation of the Combat Effectivess of Friendly Forces

Somewhat of a second cousin of the Western principle of economy of force, this dictum contains two subprinciples, which are seen by Soviet planners as mutually supporting. One aim of the principle, in common with Western theory, is the use of the minimum forces necessary to accomplish the mission. Beyond this immediate concern lies the goal of protecting the Soviet force from the actions and weapons of the opponent, maintaining it intact as an element of the battle equation.

In following the elements of the principle, therefore, great care is given to the determination of force ratios, concentration measures, and artillery support measures in order to retain as much uncommitted combat power as possible. Thus, while Soviet reserve elements at all levels would initially appear small by Western standards, careful examination reveals them to be meticulously Grafted combined arms formations of motorized rifle, tank, antitank, air defense, and combat engineer troops representing formidable combat power.

From the purely protective standpoint, most if not all dispersal and protective measures undertaken in consideration of weapons of mass destruction derive directly from the principle. Material evidence of the importance accorded the principle is found in the development and production of the latest generation of Soviet combat vehicles, all equipped with nuclear and chemical protective systems. A qualified and highly competent medical support system designed to quickly return casualties to combat fitness, the priority given to construction of protective shelters in the defense and during halts while on the march, and the system of unit rather than individual replacement, all serve to further demonstrate Soviet practical application of the preservation principle.

One extremely interesting aspect of Soviet observance of this principle lies in the logistics support system. Such logistics principles as forward siting and delivery, mobile supply bases, pipeline construction, and resupply priorities have all been specifically adopted as means of satisfying the requirements of the principle. Rapid, responsive maintenance is considered no less critical to the goal, and extensive maintenance and repair capabilities exist at all levels. Fully aware that the combat effectiveness of a highly mobile force is limited by what its logistics and maintenance services can support, the Soviets have spared no efforts in creating a system capable of meeting the demands of a high mobility combat environment.

For the opposing commander, it is precisely this logistics and maintenance system that presents the potential for drastically curtailing the combat options available to the Soviet commander. Soviet logistics and maintenance facilities should logically represent high priority targets, since to destroy the means of sustaining combat is to degrade the ability to initiate combat.

Conformity of the Goal

This Soviet expression of the principle of the objective stresses that the purpose of all operations must conform realistically to the actual situation. It may be thought of as battlefield pragmatism, aimed at keeping missions and objectives within the capabilities of available combat power, as well as the nonnegotiable factors of time and space. As in Western forces, the goal or objective is derived from the mission assigned by the senior commander or deduced from his instructions. In either event, it constitutes the starting point of the subordinate commander’s concept of operations and requires certain actions on the part of that commander and his staff:

* A thorough and accurate estimate of the situation must be made. The accuracy of the commander’s estimate is critical to the remainder of the process, since it must avoid leading to the assignment of impossible tasks with inadequate forces or losing an opportunity to defeat the enemy by overestimating his strength. Accurate and detailed intelligence regarding the opponent is an absolute necessity in the formulation of this estimate.

* There must be a substantial decision which permits the initiation or development of decisive combat action.

* The mission must be supportable by all elements, and the nature of the required support must be clearly defined and organized in detail.

* Effective means of command and control must be provided. Implicit in this principle is the unwaiverable requirement that the goal must be realized. Failure is neither excused nor tolerated. In this regard, the principle calls for the accomplishment of three interrelated tasks:

-Destruction or capture of the opponent’s forces, and the destruction or seizure of the weapons and equipment necessary for them to fight. This may be undertaken directly through engagement or indirectly through maneuver that forces the opponent into an untenable situation. Whichever course is chosen, destruction or capture of the opposing force is the premier consideration in the planning of combat action. All other objectives are considered as secondary and contributory.

-The seizure of terrain held by the enemy. The occupation of terrain for its own sake is not a consideration. Rather, occupation of terrain is predicated upon destruction of the opposing force that holds it and stems directly from the accomplishment of that task. In this respect, the two activities are considered as inseparable coelements of mission accomplishments.

-The mission must be accomplished by the prescribed time. Despite the accomplishment of the first two tasks, the requirements of the principle are considered as not having been met if completion is delayed beyond specified time limits. The degree of importance assigned to this last criterion may be seen in a number of recent major Soviet field exercises in which senior general officers were the targets of stinging rebukes from higher headquarters for failing to execute missions within prescribed time limits.

Much of what is considered in the commander’s decisionmaking process as it is practiced in Western armies is apparent in this principle. Peculiar to the Soviets is the emphasis placed upon timely mission accomplishment. Given the nature of Soviet combat operations in which the sequenced actions of separated units forms the basis of combat plans, this is understandable.

As with all combat decisionmaking, however, the accuracy of the initial estimate, as has been previously commented upon calls for unfailing intelligence support. If the opposing force effectively denies the Soviet intelligence structure the ability to function in support of this estimate, observation of the principle becomes more guesswork and less science. Certainly the most effective way to interfere with this intelligence structure and deprive the Soviet commander of its support is through the aggressive conduct of denial and deception measures. Prevented from conducting a valid analysis of the opposing force, the Soviet commander’s decisionmaking will compound error into an unsuitable combat plan.

Coordination

Coordination may be considered as the interaction of combat, combat support, and combat service support units in the execution of tightly structured combat plans. Observation of the principle seeks to ensure that each element accomplishes its various tasks when and as assigned, since the overall plan is dependent for its success upon the proper and timely discharge of its individual tasks and subtasks. More often than not, the ability of any given unit to attain its objectives is closely related to, and linked with the performance of, adjacent and supporting units.

In the execution of finely tuned combat plans in which the interplay of units must take place with precision, this emphasis upon coordination is understandable. It is deemed especially necessary in the conduct of such offensive operations as the hasty attack and the meeting engagement and in exploiting the effects of nuclear and chemical weapons.

This principle is still further evidence of Soviet attempts to structure and schedule combat operations that are essentially fluid in nature. What is relied upon is not the extemporaneous coordination of freely moving units characterized by extensive exercise of initiative on the part of junior commanders exploiting the fleeting opportunities of a rapidly changing situation. Rather, the scheduled coordination of units adhering to predetermined tasks and timetables in an attempt to control events forms the basis of the combat plan. There is scant room in this type of operation for Clausewitzian “friction” or the interference of that most ubiquitous of all battlefield menaces, “Murphy’s Law.”

The examination of the principles of Soviet tactical doctrine has shown them to be individually and collectively directed at the creation of combat conditions that deprive the opponent of tactical initiative and allow the Soviet commander to set the time, place, and terms of battle. This seizure of the initiative is the overriding thrust of Soviet military philosophy and forms a continuous thread running through doctrinal principles. This point cannot be overemphasized: the pre-eminent goal of Soviet combat decisionmaking is the conduct of battle on Soviet terms. The friendly commander who fails to recognize this has already accommodated himself to the Soviet plan.

For a friendly commander to acquiesce in a role of response is to place the Soviet force in a position of potentially decisive advantage. A friendly force faced with a Soviet opponent wielding an advantage of this magnitude faces the probability of being denied accomplishment of its mission and suffering defeat.

There must be on the part of the friendly commander, therefore, an appreciation of Soviet principles of tactical doctrine. To understand these principles is to understand the fundamental elements of all Soviet operational planning, since there is a designed relationship between the principles themselves, as well as between the principles and the combat planning process.

In understanding the applications of Soviet tactical doctrine, the friendly commander is the beneficiary of an unforseen ally. The current set of doctrinal principles represent a marked departure from military theory and practice long a trademark of Russian and Soviet forces. This change in military concepts and the new tactical theory which has emerged from it has thrust the Soviets into the midst of a paradox. Although opting for maneuver warfare with its reliance upon individual initiative and judgment at the lower levels of command, the Soviets, nevertheless, have retained a military heirarchy that works from the top down and a parallel political command structure in the form of the ever present unit political officers. Possessing the theory and material means of maneuver warfare, the Soviets find themselves with human elements of the equation that at all levels are the product of a socio-political system which requires conformity rather than individuality.

Faced with a machine in which some of the parts do not meet design specifications, what the Soviets have arrived at is a form of mutant maneuver warfare. Rather than on-the-spot initiative, much of Soviet tactics are a carefully planned and sequenced series of interdependent activities. Viewed from this perspective, the relentless emphasis upon tactical initiative is completely understandable. Any military operation dependent upon precise and timely execution cannot be interfered with if it is to be successful. It is imperative that the opponent not be allowed to interfere with the workings of the machine, for to permit this is to risk throwing the entire operation into chaos.

And yet, numerous opportunities exist for the friendly commander to effect just such a disruption; always assuming, of course, that he has the necessary weapons, equipment, and quality of troops to do so. This is possible because the very nature of Soviet tactics renders them identifiable and predictable to the alert commander who begins with a thorough understanding of Soviet doctrine.

Knowing what to look for, the friendly commander needs but to determine where on the battlefield to look for it. Here again, tactical doctrine provides the key. Through identifying and monitoring the activities of certain Soviet units, much of the Soviet commanders’ plan may be deduced and pre-empted. The location and activity of nuclear/chemical delivery units, artillery, combat engineers, and logistics elements, particularly at the divisional and combined arms army level, will almost unfailingly provide a means of projecting the movements of motorized rifle and tank formations and predicting their future activities. In any such carefully structured and sequenced combat plan, the activities of certain units cannot but help telegraph their future activities while at the same time identifying the concurrent activities of other related units.

This is not to suggest that such a result will be achieved effortlessly. It will require diligence and hard work, a sound understanding of Soviet doctrine and tactics, and a tireless, effective reconnaissance and intelligence effort. It will require also, superb fighting qualities on the part of the friendly force, which will not in any event escape the need to overcome the considerable fighting quality of the Soviet soldier, enough in itself to have altered the outcome of many battles in the past. Certainly it is a result well worth the effort invested. Only through throwing off the role of ineffectual response planned for him and seizing the tactical initiative himself may the friendly commander hope to impose his will and emerge the victor.