by Maj R.J. Brown, USMCR

Maneuver Warfare is a term that only recently entered the Marine Corps lexicon. As result, its meaning is often misunderstood by Marines. Younger officers frequently conjure up Rommelesque visions of massive armored clashes across vast green steppes or khaki-colored deserts. On the other hand, conservative Marine “purists” are turned off by the unfamiliar, foreign sounding titles used by maneuver enthusiasts to press home their arguments. In this semantic confusion, the major thrust of maneuver warfare is frequently lost. Maneuver warfare is not a new panacea to replace older, well-proven methods of warfare; rather it is a style of warfare that uses unique application of these well-proven methods to enhance the commander’s chances for success on the battlefields of today and tomorrow. One need not rely on foreign examples to see how the concepts of maneuver warfare have been applied in the past. A Marine assault carried out 40 years ago in the central Pacific provides us with an excellent example of the principles of maneuver warfare. The practitioners of this art were none other than LtGen Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, Col Evans F. Carlson, and MajGen Clifton B. Cates; familiar names that will warm the heart of any loyal Marine. The seizure of Tinian is a classic example of Marine maneuver warfare at its best.

The island of Tinian lies just off the southern tip of Saipan in the Mariana Islands. Its capture as a followup to the Saipan invasion of 1944 was obvious to both the Japanese and Americans. The problem was not “if or “when,” but only “how” to capture the island. The way this problem was solved marks the seizure of Tinian as one of the most noteworthy operations in Marine Corps history.

In 1944 Tinian presented a formidable obstacle. Over 9,000 Japanese defenders were preparing to defend the island, and the American capture of Saipan gave them ample warning of what was ahead. The Japanese force comprised the battle hardened 50th Infantry Regiment, a battalion of the 135th Infantry Regiment, the 56th Naval Guard Force, and assorted combat support units. This force was commanded by Col Keishi Ogata. The island’s interior was relatively flat, dotted with numerous sugarcane fields, and its coastline was characterized by steep coral cliffs. The only urban area on the island was built up around the sugar refinery and called Tinian Town. Reconnaissance of the island showed only three potential landing areas: one at Tinian Town, one at Asiga Bay, and one in the northwest corner near Ushi Point. The most favorable landing area, in terms of terrain, was the beach at Tinian Town. The beach at Asiga Bay was considered marginal because of tide conditions and coral reefs. Two beaches were spotted in the area near Ushi Point, but both were extremely narrow and coral reefs or small cliffs blocked portions of the approach lanes.

This was the situation as the date for the assault approached. After an in-depth review of several possible actions, Col Carlson, the man who made the Chinese phrase “Gung Ho” synonymous with Marine esprit de corps, urged a startling scheme of maneuver. He proposed that the 2d Marine Division fake a landing at Tinian Town to keep the Japanese busy, while the 4th Marine Division sneaked in the “back door” by landing across the miniscule beaches to the north. LtGen H.M. Smith listened and agreed that this “indirect approach” was best. By using this scheme, a shore-to-shore landing could be conducted under the protection of American artillery fire. A convincing demonstration at Tinian Town would tie up Japanese reserves during the crucial early hours of the landing and avoid the heavy concrete teeth Col Ogata had planted on the Tinian Town beaches. As was expected, some more conservative officers rejected this plan as too daring and controversial. It took the vociferous Gen H.M. Smith to convince them to accept the inherent risks and adopt the plan.

Once the plan of attack was worked out, the preparation for the invasion began. First, V Amphibious Corps (VAC) was task organized to perform the mission it was assigned. The two artillery regiments of the 2d and 4th Marine Divisions were radically realined. The five battalions of 105mm howitzers (two from each of the divisions and one from VAC) were united to form a provisional group under Col Raphael Griffin, the commanding officer of the 10th Marines. These guns were then placed under the command of BGen Arthur M. Harper’s XXIV Corps Artillery (U.S. Army). The remaining four 75mm pack howitzer battalions were united under Col Louis G. DeHaven (14th Marines) to form an assault artillery regiment. All of the available LVT armored amphibious tractors and DUKW unarmored amphibious trucks were placed at the disposal of Gen Cates, commanding general, 4th Marine Division. The remaining combat support units, shore party teams, tank battalions, engineer units, etc. were also attached to the 4th Division. One additional regimental combat team, RCT-8, was attached for the opening assault. Some LVTs were specially modified to emplace bridging equipment on the cliffs to allow the following waves to scale them easily. This task organization provided the Marines the tools needed to accomplish their goal.

The preparatory bombardment of Tinian was the most effective in the Pacific war. Each target was carefully selected and then struck by various supporting arms over an extended period. The island was divided into special fire support sectors and specific targets were located after careful reconnaissance. Three battleships, 3 cruisers, and 24 destroyers were used to provide naval gunfire. The 155mm “Long Tom” guns of Gen Harper’s artillery ranged the length and width of the island, and 105mm howitzers pummeled the northern portion. Daily air strikes and a new aerial weapon called “napalm” were also used to destroy enemy positions.

The landing was made on the morning of 24 July 1944 after a furious artillery, naval, and air bombardment. During the previous weeks, great care had been taken to ensure that preparatory fires would not betray the intended landing area, and the area near Tinian Town had received the lion’s share of the naval gunfire before J-day or “Jig” day (so named to avoid confusion with Saipan’s D-day and Guam’s W-day). An ominous portent of what might have happened had the landing been made at Tinian Town took place when Japanese coastal guns disabled several U.S. Navy ships supporting the demonstration force. To the north, however, all was well. The Marines flooded ashore and moved inland rapidly against only light opposition. Soon the combat support units crossed the beaches. The beachhead was quickly secured with very little cost to the attacking force.

At 1630 that afternoon the combat teams received orders to halt even though the first objective, the 0-1 line, was not yet captured. Gen Cates, a shrewd veteran of Guadalcanal, wisely decided to halt in place and dig in for night defense. While this move was contrary to the established Marine Corps amphibious doctrine that called for the landing force to move inland at all costs, this decision put Gen Cates inside the enemy’s “Boyd (observation-orientation-decision-action) Cycle.” By attacking that first night, Col Ogata’s forces played into American hands; rather than forcing the action, they reacted in the expected manner. The enemy struck in three columns. Each attack was crushed by the well-prepared Marines. Ogata merely wasted his finest troops in a futile effort that was doomed to fail because it lacked the necessary element of surprise. Gen Cates felt the Japanese “broke their backs” in these attacks and actually made the later conquest of Tinian much easier.

On 25 July the 2d Marine Division (MajGen Thomas E. Watson), having completed the demonstration off Tinian Town, came ashore over the northwest beaches, seized Ushi Airfield, and swung south with a zone of action covering the eastern half of the island.

On J-day plus 2, the second phase of the operation began. The two Marine divisions began “elbowing” their way south to Tinian Town. Each division alternated, tearing off huge chunks of real estate by operating in tank-infantry teams behind a rolling artillery barrage that was furnished by the bulk of the direct support artillery. This symbiotic relationship between men and machines worked well; the tanks crushed the cane stalks and tropical vegetation that barred the infantry’s way, while the Marines on foot provided close-in protection against antitank weapons and spotted targets for the 75mm tank guns. The main problem during this phase was keeping up with the fast-moving attack. These assault groups moved with astounding swiftness. On 27 July they burst ahead 1,800 yards. The next day they covered 6,000 yards over a 5,000-yard front. These were amazing advances when one considers the pace set during other operations in the Pacific. Tinian Town fell on 31 July, well ahead of schedule.

The capture of Tinian Town marked the beginning of the final phase of the attack. Col Ogata was killed the next morning when the Japanese struck the Marines with another banzai attack. The last days of fighting were tough ones because the Japanese were holed up in the cliffs at Marpo Point on the island’s extreme southern tip. Fighting became a deadly duel between small assault groups of Marines and the suicidal Japanese defenders. It became a battle in which neither side asked for quarter. Eventually, the Marines wore down the last pockets of defense, and the island was declared “secured” on 1 August 1944.

The battle for Tinian took only nine days. The Marines inflicted 6,050 casualties on the Japanese defenders, captured 250 Japanese soldiers, and interned 13,662 civilians. Marine losses were 290 killed, 1,515 wounded, and 24 missing in action. The Marine kill ratio (20 to 1) was the best of any major operation in the Pacific. Based on mileage per day, Tinian was also the fastest moving Marine operation during the war and a strategic victory of the greatest magnitude. Its flat fields soon sprouted numerous airfields big enough to support the lumbering Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers that bombed Japan around the clock. On 6 August 1945 the B-29 Enola Gay left Tinian for Hiroshima where it dropped its atomic payload and brought the world into the nuclear age. For their fine performance in the Marianas, the Marine divisions were each awarded a Presidential Unit Citation. The ultimate tribute came when Gen H.M. Smith called Tinian the “perfect amphibious operation.”

What lessons can this battle fought four decades ago present to a commander using modern weaponry? The answer is many. Although the weapons and tactics have changed in the intervening years, the principles behind the victory at Tinian are as meaningful today as they were in 1944. The first and most important concept in maneuver warfare was the proper use of Basil Liddell Hart’s concept of the “indirect approach,” advocated most forcefully in his book Strategy. The indirect approach does not mean using an off-the-wall scheme of maneuver, hoping to catch the enemy off guard. It is a method of entering the enemy’s “Boyd Cycle” and throwing him off balance. Properly applied, it achieves such surprise that the enemy is put into a psychological and physical state from which he cannot recover. The attacking (or surprising) force gains the upper hand and forces the enemy to react at the wrong time and to the wrong stimuli. In the words of Sun Tzu, “Appear at places the enemy must hasten to defend, march swiftly to places where you are not expected.” This concept was properly applied at Tinian. The feint of the 2d Marine Division was meaningful because the enemy believed Tinian Town would be attacked and drew his forces away from the actual landing area. Feints were used several other times in the Pacific, but most encountered little success because they did not present a believable scheme of attack. A second example of sound fundamental tactical judgment was Gen Cates’ decision to stop short of the 0-1 line and dig in. He anticipated the Japanese attack; he enticed the Japanese to make it; and he decimated them along the barbed wire that ringed the Marine lines.

Another fundamental principle of maneuver warfare carefully observed at Tinian was exploitation of the situation and methods at hand to accomplish the task. The decision to land at the White Beaches was not a rash gamble, but rather a calculated risk. The enemy’s plans, preparations, and “mind set” were carefully studied. The risk was weighed against the potential gain. It was decided that if the enemy did fall for the ruse and was surprised by the Marine landings, he would be demoralized and placed at a physical and psychological disadvantage. These advantages were carefully weighed against the more conservative, but surely more costly, landings at Tinian Town. Each factor was carefully considered: the available fire support, the logistical burden, the terrain, and the weakened condition of the assault force that was tired from the Saipan campaign and had not been reinforced by sufficient replacements. In the end, the “back door” was judged the best possible scheme of maneuver for the forces available because it was within the capabilities and exploited their strengths.

The area that showed the most originality was that of task organization. The task organization of artillery for Tinian was truly unique and clearly showed the concern of the commanders for the principles of war. The availability of shore-based artillery support during the entire landing phase was the deciding factor in the task organization. By placing all the “stay behind” artillery under a single commander, the principle of unity of command was observed; and the massed fires of the 156 artillery pieces left on Saipan utilized the principles of mass and economy of force. These stationary guns, firing from near their supply points lobbed accurate, continuous observed fire on to the Japanese from well before J-day until well after the assault artillery was ashore. At the same time, landing the 75mm pack howitzers with the assault troops guaranteed responsive direct support for the maneuver force. The common pooling of the other combat support units was consistent with the principle of economy of force. The tank-infantry operations on Tinian were the smoothest of any in the Pacific Campaign. All in all, the task organization at Tinian was an excellent model for future operations.

As in any attack, a well-constructed fire support plan is mandatory if the indirect approach is to succeed. Only a fool will neglect his fire support. A good commander will use a scheme of maneuver that will maximize the effectiveness of all available supporting arms and at the same time use an unexpected avenue of approach. At Tinian, use of the most modern weapons, such as napalm, coupled with tactical flexibility produced a successful operation. The careful preparatory fires using close air support, naval gunfire, and shore-based artillery were a hallmark of integrated arms. The fire support plan used at Tinian was original and well-thought-out. Each of the available combined arms was used to its fullest capability. The planners assigned the tasks to be done, placed one person (or agency) in charge, and left the detailed execution of fire support to the experts. (It is interesting to note that a U.S. Army general was placed in command of the artillery, despite the infamous “Smith vs. Smith” controversy that erupted at Saipan, causing untold inter-Service strife.* The smooth coordination of the artillery at Tinian should be used as an example of interService cooperation that destroyed the myth that the Army and the Marines could not work together.) The fire support at Tinian was a tribute to the concept of combined arms and is a prime example of what a good fire support plan should be.

The final area was logistics. Logistics is a dirty word to some commanders, yet no other phase of an operation may be more important. Many great tacticians of the past have been undone by logistics, and the great commanders of this time-Erwin Rommel, George Patton, and Bernard Montgomery-were all victims of poor logistical planning. It is a fact of life that the scheme of maneuver will be dependent on logistical support. If the “beans, bullets, and band-aids” don’t make it to the maneuver units, they will quickly become “lack of maneuver” units. Tinian was a good example of the principle of adapting logistics to the scheme of maneuver. At Tinian a reinforced corps was landed over a difficult reef and across 2 beaches of less than 200 yards. In nine days of heavy combat not a single pound of supplies was handled in the normal shore party manner, yet, at no time did the landing force suffer any crucial supply shortages. The use of special LVTs to scale the small cliffs in the landing area and specially made landing docks were examples of innovative solutions for specific problems. The decision to use the wheels and tracks of the amphibious vehicles to provide the bulk of the logistic support and move directly inland was sound and imaginative. Modern commanders must pay particular heed to the logistics burden because modern weapons use up gas and ammunition at staggering rates.

Wise commanders have always looked to the past in order to plan for the future. The modern helicopters that make vertical envelopment possible, the amphibious assault vehicles and tanks that mesh to form mechanized combined arms task forces, the light armored vehicles designed to increase Marine mobility, the air-cushioned landing craft of the future-each is only a tool for the modern commander. As tools they cannot and, indeed, are not intended to replace the principles of war. In fact, if not used properly, these state of the art tools may only push our logistical assets beyond the breaking point. A smart commander will keep this in mind while he applies the well-proven principles, the same principles applied so soundly by Gen H.M. Smith, Col Carlson, and Gen Cates at Tinian; a plan of attack that is within the capabilities of the combat team and uses an “indirect approach” when possible, a solid fire support plan with all arms operating in concert, a flexible task organization that fits the plan of attack, and a realistic logistics plan that can keep abreast of the attack. These few principles have been the keys to victory countless times in the past and will continue to unlock the door to victory on the battlefields of the future. These lessons are the heritage of Tinian, one of the most successful amphibious operations in history.

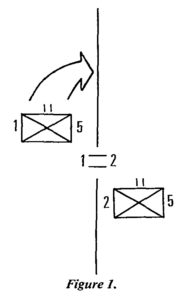

What about control measures, boundaries, and coordination lines? (Here the interviewer drew a sketch similar to Figure 1.) What if the 1st Battalion were to become aware of an opportunity to attack the enemy in 2d Battalion ‘s zone? Say 2d Battalion has no forces in this upper part of his zone now. Whom must 1st Battalion coordinate with in order to cross over into or call fire into 2d Battalion ‘s zone?

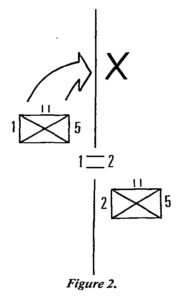

What about control measures, boundaries, and coordination lines? (Here the interviewer drew a sketch similar to Figure 1.) What if the 1st Battalion were to become aware of an opportunity to attack the enemy in 2d Battalion ‘s zone? Say 2d Battalion has no forces in this upper part of his zone now. Whom must 1st Battalion coordinate with in order to cross over into or call fire into 2d Battalion ‘s zone? must control the fire. Otherwise, you miss opportunities. Your response will be too slow. The decision is always made by the one who is able to see the situation right there on the battlefield. Even if the division commander might be smarter, in a situation like that, the lieutenant’s decision might be more important than the general’s.

must control the fire. Otherwise, you miss opportunities. Your response will be too slow. The decision is always made by the one who is able to see the situation right there on the battlefield. Even if the division commander might be smarter, in a situation like that, the lieutenant’s decision might be more important than the general’s.