Picture this scene. A wardroom at sea or an officers club on Okinawa. Bored Marine officers grab bowls of popcorn and glasses of bug juice, then settle down to another exciting movie-“Friday the Thirteenth, Part 6.” Two more hours of an unaccompanied tour pass in mind-numbing passivity. Why? Aren’t there alternatives that could make positive use of the literally thousands of manhours wasted in this fashion.

The answer is an emphatic “Yes.” Two relatively inexpensive options can make these hours not only productive but enjoyable. They are battalion-level professional libraries and commercial wargames. These two simple tools combined with command interest can make much of this time both fun and educational.

Each battalion can create its own extensive professional library for a deployment by using the following method. First, assign a study group from within the battalion-include various ranks and MOSs. They will be tasked with developing a recommended reading and wargaming list for the battalion. Once this list has been developed, each officer will select two or three books or wargames from the battalion’s list and purchase them. The battalion will then consolidate the purchases into a library, use them for the duration of the deployment, and return them to their owners at the end of the tour.

As a starting point, I am going to recommend a basic library and a collection of wargames for an infantry battalion. This is only a starting point, the actual selection should be made by each battalion’s study group.

BOOKS

My recommended book selections can be broken down into several major subject areas. Remember, these selections represent only one person’s reading-consider them, discuss them, and recommend your favorites.

Leadership-The Human Factor

In a time of increasing emphasis on the technical aspects of war, these books will give the reader a better understanding of the most important element in war-man.

MEN AGAINST FIRE: The Problem of Battle Command in Future War. By S.L.A. Marshall. Peter Smith, Gloucester, Mass., 1978, 215 pp.

A military classic, this volume makes a detailed examination of how men react to fire and what the small unit leader can do to prepare his men for this ordeal. Also contained are superb insights and recommendations on commanding units in combat. This should be required reading for all combat arms leaders.

SOLDIER’S LOAD AND MOBILITY OF A NATION. By S.L.A. Marshall. Marine Corps Association, Quantico, Va., 1980, 120 pp., $9.95. (Member $8.96)

Another classic by BGen Marshall, this is a comprehensive look at the load an individual Marine should carry into combat. The after action reports from Grenada indicate this is a lesson relearned every time there is a war. The book contains critical information for an infantry officer.

THE FACE OF BATTLE. By John Keegan. Penguin Books, New York, 1976, 365 pp., $17.00. (Member $15.30)

This is a fascinating study of the battles of Agincourt, Waterloo, and the Somme with emphasis on the physical and psychological effects on the soldiers fighting in these actions. Keegan is a thoughtful writer and has much to offer professionals with his insightful analyses.

COMBAT MOTIVATION: The Behavior of Soldiers in Battle. By Anthony Kellett. Kluwer Nijoff Publishing, Boston, Mass., 1982, 362 pp.

An excellent companion to Men Against Fire, this is a comprehensive, well documented study of why men fight.

BATTLE LEADERSHIP. By Capt Adolph von Schell. Reprinted by the Marine Corps Association, Quantico, Va., 1982,95 pp., $9.95. (Member $8.96)

This book consists of a collection of Capt von Schell’s post-World War I lectures to the United States Army Infantry School dealing with action on the Eastern Front in World War I. The observations on small unit leadership and tactics are as applicable today as they were in 1918.

THE ARNHEITER AFFAIR. By Neil Sheehan.

This work traces the events that led to a near mutiny aboard the USS Vance off the coast of Vietnam. It is a thought-provoking story with plenty of substance for leadership and ethics discussions.

COMMON SENSE TRAINING. By LtGen Arthur S. Collins, Jr., USA(Ret). Presidio Press, Novato, Calif., 1978, 225 pp.

This book contains practical, usable tips to improve day-to-day training from platoon to division. It is a volume to be kept and reread each time Marines return to the Fleet Marine Force.

FOLLOW ME: The Human Element in Leadership. By MajGen Aubrey S. Newman, USA(Ret). Presidio Press, Novato, Calif., 1981, 323 pp.

One of the outstanding books on leadership in print, this work provides useful insights on command presence, command techniques, and command in battle.

STARSHIP TROOPERS. By Robert A. Heinlein. Berkley, N.Y. 1959, 208 pp., $9.99. (Member $9.00)

This is a scintillating, fast-moving science fiction yam about a future armed force that bears a striking resemblance to the U.S. Marine Corps. It should be read for the underlying themes of personal responsibility, leadership, and dedication to service. It makes just plain fun reading.

MAKERS OF MODERN STRATEGY: Military Thought from Machiavelli to Hitler. Ed. by Edward M. Earie. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 1971, 533 pp., $57.50. (Member $49.99)

Twenty authors examine warfare during the last 400 years. This volume helps build a professional’s understanding of the development of strategy and tactics.

CRISIS IN COMMAND: Mismanagement in the Army. By Richard A. Gabriel and P.L. Savage, Hill and Wang, New York, 1978, 242 pp.

Two concerned former Army officers look into the problems the Army brought on itself during the Vietnam conflict. It should be read by all professionals to ensure these mistakes are not repeated in the next full-scale conflict.

Amphibious Warfare

Although amphibious warfare is the Corps’ bread and butter, many Marine officers lack background on the development of amphibious doctrine. These books help fin that gap and increase the individual’s appreciation for the complexities of these operations.

ASSAULT FROM THE SEA: Essays on the History of Amphibious Warfare. By LtCol M.L. Bartlett, USMC(Ret). Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 1983, 312 pp., $32.95. (Member $29.66)

This collection of essays written by authors from many nations on amphibious operations throughout history broadens the professional’s understanding of this unique mission.

THE U.S. MARINES AND AMPHIBIOUS WARFARE. By J. Isley and P. Crowl. Marine Corps Association, Quantico, Va., 1979, 636 pp.

This classic gives a comprehensive overview of the Corps’ development of amphibious doctrine and the painful refinement of those techniques during World War II.

VICTORY AT HIGH TIDE. By Col Robert D. Heinl, Jr., Nautical and Aviation Publishing Company of America, Annapolis, Md., 1979, 315 pp.

Heinl provides an outstanding history of the 1st Marine Division’s landing at Inchon and the subsequent drive on Seoul. It makes fascinating reading from both the historical and operational perspectives.

THE BATTLE FOR THE FALKLANDS. By Max Hastings and Simon Jennings. W.W. Norton Co., New York, 1983, 357 pp.

An excellent history of the Falklands War, the authors cover both the expeditionary force and the corridors of Whitehall. It is of particular interest for Marines because of the difficulties the British experienced conducting an amphibious landing under extremely difficult conditions with insufficient strategic lift.

Maneuver Warfare

Currently a much discussed topic in the Corps, maneuver warfare requires a strong background in its principles to develop the mindset required for operationalizing its concepts. The books of this section will introduce the reader to maneuver as developed and practiced by acknowledged masters.

THE ART OF WAR. By Sun Tzu, Translated by Samuel B. Griffith. Oxford University Press, New York, 1963, 197 pp., $11.95. (Member $10.76)

The earliest recorded maxims of war, this book is still clear, concise , and remains applicable. This short volume is well organized to facilitate study.

STRATEGY. By B.H. Liddell Hart. New American Library Inc., New York, 1974, 426 pp.

This noted author provides a carefully developed historical study of the benefits of the indirect approach. It is a must for those wishing to study the evolution of military doctrine in the 20th century.

THE ROMMEL PAPERS. Ed. by B.H. Liddell Hart. Da Capo, New York, 1982, 544 pp.

Hart compiled, edited, and provided background on Rommel’s personal account of his actions in World War II. Of particular interest is Rommel’s style of leadership in a fast-moving environment.

SHERMAN: Soldier, Realist, American. By B.H. UddeU Hart. Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn., 1978, 456 pp.

This fascinating biography traces Sherman’s development from civilian to master strategist and proponent of maneuver warfare.

STONEWALL IN THE VALLEY. By Robert G. Tanner.

This volume highlights Stonewall Jackson’s style of maneuver warfare and his masterful use of meager forces to tie down much larger Union forces thereby disrupting the North’s entire strategy.

LOST VICTORIES. By Field Marshall Erich von Manstein. Presidio Press, Novato, Calif., 1982, 574 pp.

PANZER LEADER. By Gen Heinz Guderian. Zenger Publishing Co., Inc., Washington, D.C., 1952, 528 pp.

PANZER BATTLES. By MajGen F.W. von Mellenthin. Ballantine Books, New York, 458 pp., 1971.

These accounts of the German Army in World War II trace the development of maneuver warfare and its refinement by these acknowledged masters.

ON THE BANKS OF THE SUEZ. By MajGen Avraham Adan (Israeli division commander during the 1973 war). Presidio Press, Novato, Calif., 1980.

THE CROSSING OF THE SUEZ. By LtGen Saad el Shazly (Chief of Staff of the Egyptian Army during the 1973 war). American Mideast Research, San Francisco, Calif., 1980, 333 pp.

THE ARAB-ISRAELI WARS: War and Peace in the Middle East. By Chaim Herzog. Random House, New York, 1982, 392 pp.

NO VICTOR, NO VANQUISHED: The Yom Kippur War. By Edgar O’Ballance. Presidio Press, Novato, Calif., 370 pp.

These books provide excellent accounts of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War from four very different perspectives. A wealth of information on modern armored warfare is provided. Also of note are the conflicts between the accounts.

Tactics

These volumes cover numerous actions in varied conditions and times. Many of the individual cases provide excellent material for discussion on how tactical lessons and principles may be applied.

INFANTRY IN BATTLE. By the Infantry Journal.Mantte Corps Association, Quantico, Va., 1982, 422 pp.

From the Marine Corps Association Heritage Library, this is an outstanding study of small unit action in World War I. At the conclusion of each chapter is a lucid discussion of the tactical precepts emphasized by that action.

SMALL UNIT ACTION IN VIETNAM, 1966. By Capt F.J. West, Jr., USMCR. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, Washington, D.C., 1967,123 pp.

This is a well written account of small unit actions involving Marine units in Vietnam. This volume does for the Corps what BGen Marshall’s Ambush did for the Army.

VIETNAM PRIMER. By S.L.A. Marshall. Lancer Militaria, Sims, Ark., 1967, 58 pp., $6.00.

This brief work analyzes lessons learned about small unit action in Vietnam during 1966. These lessons are timeless and serve as an interesting extension of Men Against Fire.

THE FIELDS OF BAMBOO. By S.L.A. Marshall.

Once again SLAM brings history to life with a detailed examination of three battles in the Republic of Vietnam during 1966-67. More lessons on the psychology of warrior and one guerrilla warfare.

A PERSPECTIVE ON INFANTRY. By LtCol John A. English. Praeger Publishing, New York, 1981, 368 pp.

LtCol English has written a broad study on various infantry organizations with emphasis on the development of Western armies. He provides today’s Marine officer with a historical background against which to evaluate his/her organization and training.

ATTACKS. By Field Marshall Erwin Rommel. Athena Press, Vienna, Va., 1979,325 pp., $17.50. (Member $15.75)

An autobiographical account of Rommel’s service in World War I, the reader gains interesting insight into small unit tactics by studying Rommel’s handling of his units.

IF GERMANY ATTACKS: The Battle in Depth in the West. By Capt G.C. Wynne. Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn., 1976. 343 pp.

This is a study of the development of the German defense in depth of their western front from 1915 to 1918. It is particularly interesting in light of NATO’s seated defensive plans for western Europe.

THE RIVER AND THE GAUNTLET: Defeat of the Eighth Army by the Chinese Communist Forces, November 1950. By S.L.A. Marshall. Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn., 1970, 385 pp.

This work is the story of the Chinese assault on the Eighth Army in Korea and the subsequent disintegration of the 2d Infantry Division. Many lessons are contained for command and staff alike.

Vietnam

The dominant factor in shaping our recent history, Vietnam remains a controversial and emotional issue. These books give a broad range of views on how and why we became entangled in Vietnam, how we fought, and why we withdrew.

STRANGE WAR, STRANGE STRATEGY. By Gen Lewis Walt, USMC(Ret).

This is an interesting history of Marine actions and unusual approach to pacification in the Vietnam war. Gen Walt’s position as commanding general of Marine forces in Vietnam from 1965 to mid-1967 makes this a unique account.

THE BETRAYAL, By LtCol William Corson, USMC.

The story of the Marine Combined Action Platoons in Vietnam by one of the men who commanded them.

WAR COMES TO LONG AN. By Jeffrey Race. University of California Press, Berkley, Calif., 1972, 299 pp.

The author, who spent four years in Long An Province outside Saigon, gives us a villager’s view of the conflict in this province from 1954 to 1965. This account is particularly interesting in that Mr. Race first saw Long An during his tour as an advisor and later returned as an independent researcher to gather the information for his book.

A SOLDIER REPORTS. By Gen William Westmorland, USA(Ret). Dell Publishing Co., New York, 1980, 608 pp.

This is Gen Westmoreland’s account of what the Vietnam War looked like from his position as commander. These are very interesting contrasts with the other books in this section.

ON STRATEGY: A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War. By Col Harry G. Summers, USA. Dell Publishing Co., New York, 1982, 288 pp.

Col Summers provides a thought-provoking analysis of the Vietnam War based on the Clausewitzian principles of war. His work is particularly applicable considering current events in Central America.

VIETNAM: A HISTORY. By Stanley Karnow. The Viking Press, New York, 1983, 752 pp.

THE 10,000 DAY WAR. By Michael Maclear. Avon Books, New York, 1982, 384 pp.

Both are carefully written accounts of the conflict in Vietnam from the 1940s to the 1970s. Good background information is provided for continued study on Vietnam.

OUR VIETNAM NIGHTMARE. By Marguerite Higgins.

Written in 1965, Ms. Higgins’ account covers the period from mid-1963 to mid-1965. Her account of the “popular” revolution against the Diem regime stands in stark conflict to the generally accepted version told in the two previous books. This work should be read for its crisp observations undiluted by the turmoil of the following years.

OUR ENDLESS WAR: Inside Vietnam. By Gen Tran Van Don. Presidio Press, Novato, Calif., 1978, 274 pp.

This is a fascinating insider’s account of the American period of the Vietnam War by a Vietnamese general who was close to the center of power from the very beginning.

The Enemy

Under the category of knowing the enemy, these two works give views that sharply contrast with official threat briefings.

THE LIBERATORS. By Victor Suvorov. W.W. Norton and Co., New York, 1981, 202 pp.

An insider’s account of being a company grade officer in the Soviet Army written by Victor Suvorov, a Russian defector who took the name of a famous Russian general to tell his story. His account covers his service as commander of a Soviet motorized rifle company and includes his participation in the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

INSIDE THE SOVIET ARMY. By Victor Suvorov. Berkley Publishing Co., Inc., New York, 1984, 296 pp.

This is an overview of the Soviet Army’s organization, concepts, and training.

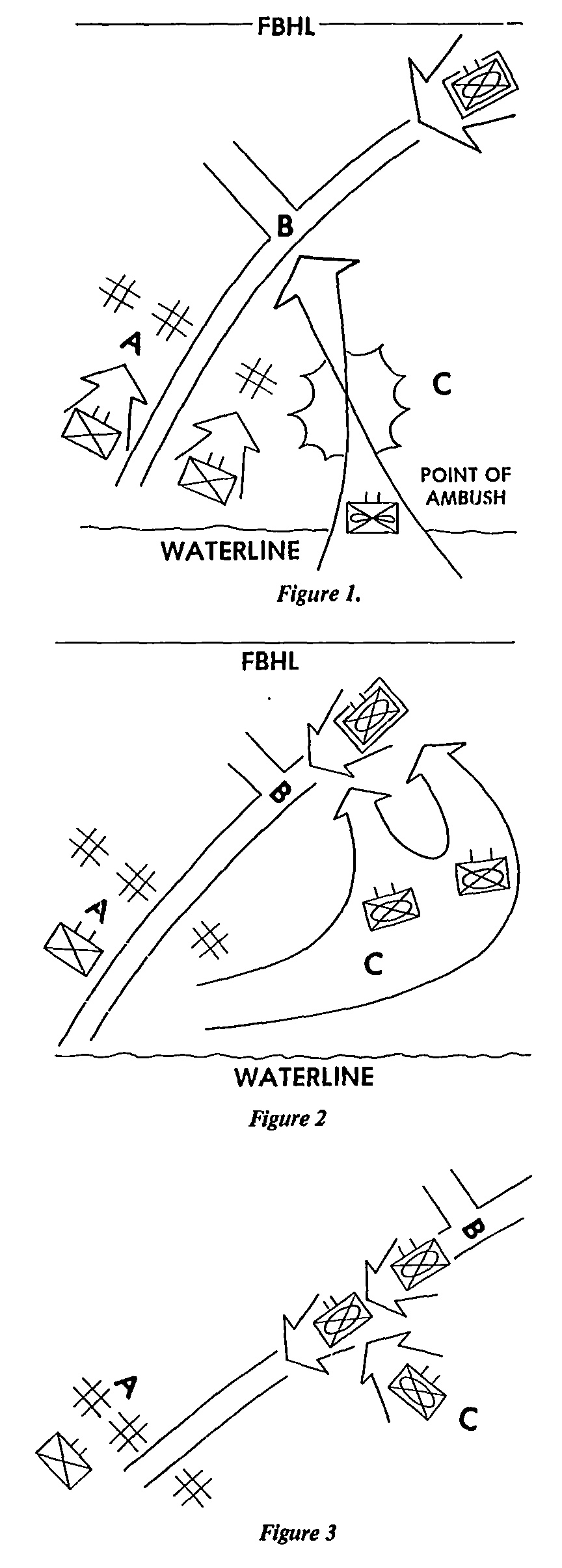

WARGAMES

The second readily available resource that can improve officer and noncommissioned officer training in the FMF is commercial wargaming. LtCol P.D. Reissner, USMC(Ret) already provided an excellent discussion of the benefits of wargaming as well as a good list of commercially available games (MCG, Mar84, p64). In addition to the games he lists, “Firefight” is an excellent basic game that will teach officers and NCOs alike first maneuver and then maneuver with indirect fire support. Although an older game, copies may be available from U.S. Army TASO offices at no charge.

SOURCES

Since the purchase of both wargames and books will have to be done by battalion officers, a look at sources would be useful. For books, the obvious place to start is the Marine Corps Association Bookservice. Simply write them with your shopping list, and they will respond promptly with what they have available and will often recommend sources for volumes they don’t stock. Next, try bookstores specializing in history. Another virtually untapped source is used bookstores. Often the proprietors of used bookstores are men or women who have made a hobby of studying military history. They can not only provide books at a reduced price but will often recommend further reading on a particular subject.

Wargames are most often stocked by hobby shops that carry an extensive line of military models. If these stores don’t have the ganies, they usually know where to get them. All of these sources are found simply by using the telephone.

Once the books and games have been obtained, the possibilities are unlimited. Marines thrive on competition, so form teams and challenge each other. Research how some of the great minds of history have approached a problem, study their solutions, and then see if you can apply the principles to your game. Competition generates enthusiasm, enthusiasm generates study, and study improves skills.

Now let’s revisualize the opening scene of this article-it’s a stateroom at sea or a company office on Okinawa. Intense officers and NCOs are gathered around a game board. Kibitzers are discussing the problem and harassing the participants. Tension runs high as commanders maneuver to destroy each other. Fire is traded, the victor smells blood and closes for the kill. This is serious-bragging rights and beer rest on the outcome. Two more hours of an unaccompanied tour pass in an atmosphere of camaraderie and learning. These are truly big returns on a comparatively small investment.

Quote to Ponder:

Individuality

“The deepest joy in life is to be creative. To find an undeveloped situation, to see the possibilities, to decide upon a course of action, and then devote the whole of one’s resources to carrying it out, even if it means battling against the stream of contemporary opinion is a satisfaction in comparison with which superficial pleasures are trivial. But to create you must care. You must be willing to speak out.”

-Adm H.G. Rickover, USN

Quoted in To Get the Job Done (p.139)

In an attempt to break out

In an attempt to break out