by Maj Jeffrey L. Seavy

“Congress has shown the same strong confidence in the Corps’ reliability. This precious confidence can be maintained only by a religious dedication to one thing that impresses congressional members, and that one thing is performance. Performance, in its turn, is geared to readiness, not just readiness but readiness to go and win-and then come home alive. Without steady, reliable performance, year in and year out. Congress would never have so consistently stood by the Marines in their times of trial. Performance is what it is all about.”

-LtGen Victor H. Krulak1

America is in perpetual financial distress. The Marine Corps must evolve and improve in an efficient and fiscally defensible manner. It must be fiscally defensible to the Secretary of Defense, the President, and Congress. While doing so, the Marines must dramatically increase capabilities over adversaries and the enemy. The threat is “rooted in attitudes or aspirations of the Army, the Navy, or various chief executives, its nature has varied-threat to the Corps’ repute, to its right to fight, to its very survival.”1 Therefore, the Corps performance must continue to improve to ensure battlefield victory and institutional survival.

The Marine Corps needs to make significant investments to improve capability and capacity to operate and fight in the urban littorals. In the next 15 years, the Service will need to modify how it organizes, trains, and equips to remain the Nation’s force-in-readiness, and it will need to do this at a bargain price. This article will focus on what significant investments the Marine Corps needs to make to create capabilities and capacities necessary to fight on tomorrow’s battlefields.

When there is a challenge, the Marine Corps normally looks first to a technological solution. During the last 15 years of war, an entire generation of Marines has become accustom to buying their way out of problems. It was Boyd, the father of maneuver warfare who said, “The military believes most of all in hardware, but people should come first. Then ideas. And then hardware.”2 This article will use Boyd’s lens of people, ideas, and equipment to explore ways to raise the bar and expand the Marine Corps’ urban capability.

People

The term “urban” is very general- it could mean anything from shanty towns to high-rise buildings. Urban terrain is especially complex because of the abrupt changes and angles, both physically and politically. Urban littoral operations can achieve improved outcomes and lower risk with Marines who can see the hazards and have the savvy to exploit the opportunities like those found in a three block war.3 It was common a few years ago, when talking about developing Marines, to say that “we’re aiming to put a gunnery sergeant head on a PFC’s body.” The idea was to take a young Marine and imbue him with all the insight and experience of a Marine a decade older. Real experience, however, is earned. Mentoring alone cannot take its place. Both Geoff Colvin’s book Talent is Overrated and Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers discuss the 10,000 hour rule4 and how it takes approximately that much time to gain the experience necessary to fully master a job. It takes time to gain experience, both for individuals and units.

So what is experience?

Training + Education + Real World and Daily

Operations – Experience

This article assumes a Marine with experience has the wisdom needed to make better decisions.

The Marine Corps starts with raw recruits-the Service does an outstanding job recruiting the best young men and women in America. Therefore, only marginal increases can be made through improved recruiting. The Marine Corps does an outstanding job with training and education. In the last 20 years, great strides have been made with ranges, highly realistic simulators, and unit training techniques. All of these improvements have resulted in a superior Corps and its ability to provide a successful, forward deployed force.

Now and in the future, the Corps absolutely needs to continue to improve TTP (tactics, techniques, and procedures). It needs to raise mental and physical standards when readiness gains result. The problem is the Service has reached a point of marginal and diminishing returns under the current training model, i.e., it is impossible to put a gunnery sergeant’s head on a PFC’s body, and that is why an experienced military force is so difficult to form. It takes time to acquire experience, and there isn’t a short cut.

Risks and Opportunities

The Marine Corps had a very different operational capability 150 years ago. In 1894, William F. Fullam, USN, first proposed to reorganize the Marine Corps into six ready expeditionary battalions to support the fleet or U.S. foreign policy.-5 Although, at the time, the institution did not respond well to his suggestion, the Marine Corps did evolve, and it is evolving today to develop a better capability.

New soldiers, Sailors, airmen, and Marines can be trained in a matter of months, but the experience the Nation often demands takes many years acquire. The bar has been raised by the American public and the Nation’s leaders. It takes far too many years to have the experience and capability needed to continue to be considered a key player by our national leadership.

The Marine Corps is losing the battle for the right to fight on several fronts. The question is not one of ability to execute-it is a question of being selected. The Marine Corps is being beat by better trained and equipped units from the other Services. The Marine Corps only needs to find a few innovative ways to close the gaps on its weakness and seize the opportunities with its strengths. The Navy/Marine Corps Team has a unique readiness position which resonates well in Congress. They have a packaged “army,” “air force,” and navy, i.e., a MAGTF aboard L-Class ships. This forward deployed capability gives the Marine Corps ownership of the word readiness.6 The ownership of the word readiness needs to be protected by ensuring mission performance.

The Marine Corps is in the business of providing the Nation with a guarantee of military performance. There are numerous examples of when experience has made the difference. In Ken Burn’s film, The Civil War, it was BG John Buford’s experience that made the difference at Gettysburg.7 In Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Blink, LtGen Paul K. Van Riper, USMC(Ret), discussed Chancellorsville8 and how the battle came down to some ineffable, magical decision-making ability that GEN Robert E. Lee possessed and GEN Joseph Hooker did not. Lee had more experience with complicated tactical situations. He learned to instinctively use the principles of war-and had the experience to creatively break those principles, as he did at the Battle of Chancellorsville.

The judgment and wisdom gained by experience separates winners and losers. In COL T.N. Dupuy’s book, A Genius for War, he discusses the importance the German General Staff played in the success of the army and how institutional experience drove individual wisdom and performance.^ Mary Walton’s book, DemingManagement at Work, discusses how Marine Col Jerald B. Gartman needed a critical mass of experienced people to carry out his mission.10 In Roger W. Claire’s book, Raid on the Sun, the 1980 Israel operation to destroy Iraq’s nuclear reactor was executed by highly experienced and specially selected team of pilots.11

The Marine Corps cannot quickly train an experienced force. Special operations communities have shown the value of concentrated pools of experienced soldiers and Sailors. The Marine Corps needs to raise its game to a new higher standard. The Marine Corps needs to further re-invest in Marines who are proven performers.

Ideas

The Army, Navy, and Air Force have an average age of 29 to 30 years. The Marine Corps is the youngest, with an average age of 25 years.12 The Marine Corps has had good results providing these young Marines with outstanding training and first class equipment; however, the Marines Corps has largely maximized its operational capability with this model:

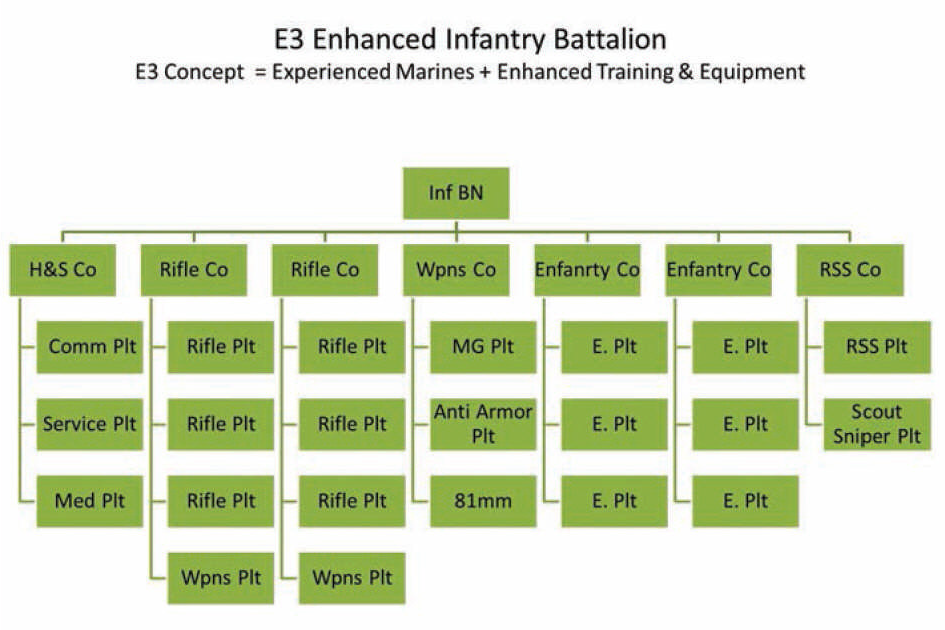

E3 – Experienced Marines + Enhanced Training and Equipment

The Marine Corps needs to seize the opportunity and capitalize on its experienced Marines to make material improvements. The Service should build concentrated pools of experienced Marines by adopting an E3 concept, which would convert between 5 percent to 30 percent of structure from within selected units, currently filled by first-term Marines, and trade it for second-term and career Marines. Only MOSs and units which could significantly increase capability would be selected. The concept would affect less than five percent of total structure.

An E3 concept uses experienced second term and career Marines to form units. These units would conduct training according to the respective training and readiness (T&R) manual13 to meet mission essential tasks and specific mission essential task lists for a unit’s individual mission analysis. These units would execute T&R tasks to a higher standard and would take on additional tasks. Marines in these units would be provided with enhanced training and equipment.

The Urban littoral environment is the most complex, dangerous, and “man intensive” terrain in which to conduct military operations-“MOUT eats infantry.” E3 units (experienced Marines, enhanced training and equipment) would more efficiently and effectively execute these operations. These E3 units would have a higher base line level of experience and wisdom, which will allow them a jump start on the lower end 1000 to 3000 T&R tasks. These experienced Marines will quickly accelerate to collective 4000 to 6000 tasks and the respective E-coded events.1’1

An Illustration of the E3 Concept- Infantry Battalion

The E3 concept provides a path to improve performance in infantry battalion mission essential tasks and specific unit mission essential tasks lists. It opens the door for units to develop new T&R tasks and events based on the higher potential these experienced units are likely to achieve, e.g., operationalization of company landing team (CLT) concept and single ship deployers as outlined in Expeditionary Force 21E The E3 concept will result in higher standards and enhanced capabilities for the forward deployed force.

Imagine an infantry battalion with one less rifle company {–182 Marines), traded for two T9 Marine E3 enhanced infantry companies and one T9 Marine E3 reconnaissance scout sniper company (RSS). These E3 units would be led by major company commanders, captain platoon commanders, and SNCO section leaders, with the balance of the unit being made up of mostly NCOs. The remainder of the infantry battalion would be made up of two rifle companies {–198 Marines), with 15 Marines added to execute distributed/company landing team operations,16 a standard table of organization and equipment weapons company and the headquarters and services company {minus scout sniper platoon). {See Figure 1.)

Enhanced Infantry Company {Enfantry)

The E3 enhanced infantry company, which this article will now refer to as the “enfantry company,” is led by a major company commander, a captain executive officer, a first sergeant, a master sergeant operations chief, a gunnery sergeant logistics chief, a staff sergeant intelligence chief, a staff sergeant communications chief, corporal radio operator, corporal cyber exploitation technician {for local attack and defense interface), and one petty officer first class independent duty corpsman. The company has three platoons, led by a captain platoon commander, a gunnery sergeant platoon sergeant, sergeant intelligence chief, a sergeant of radio chief, and a petty officer second class independent duty corpsman. The platoons are made up of three sections, each led by a staff sergeant, with a sergeant assistant section leader, a corporal radio operator, a corporal automatic rifleman, a lance corporal grenadier, and a petty officer third class corpsman.

The enfantry company is designed to be employed as a company or as an individual platoons. For example, the platoons are large enough to secure and isolate {cordon) an objective areas and still have enough Marines to provide support to an assault force, which would reduce the objective. Sections are the base tactical unit designed to act independently for short durations. Each platoon and section would have a balanced infantry MOS mix. There would be a heavy dose of MOS cross training. Crew-served weapons would include: two medium machine guns, two SMAWs, and two 60mm mortars. These weapons would be held at the company level but maintained, and checked out by sections depending on the mission requirements. (See Figure 2 on previous page.)

Reconnaissance Scout Sniper Company (RSS) Company

The RSS company is led by a major company commander, captain executive officer, first sergeant, master sergeant operations chief, gunnery sergeant logistics chief, staff sergeant intelligence chief, a corporal intelligence analysis, staff sergeant radio chief two corporal radio operators, and one first class independent duty corpsman. The company is made up of two different platoons: a reconnaissance platoon with three sections and a scout sniper platoon with eight teams.

The reconnaissance platoon is led by a captain platoon commander and a gunnery sergeant platoon sergeant. The base unit of the platoon is a section, each led by a staff sergeant, with a sergeant assistant section leader, a corporal radio operator, a corporal automatic rifleman, a lance corporal grenadier, and a petty officer third class corpsman. This unit is designed and optimized to conduct reconnaissance missions for a battalion executing distributed operations, while supporting collection activities of the greater G CE and MAGTF. The section is built to conduct independent operations for several days or weeks.

The scout sniper platoon has eight sniper teams and is led by a 0203 first lieutenant platoon commander and a master sergeant platoon sergeant. The teams are made up of the following: two teams made up of a gunnery sergeant and a sergeant, two teams made up of a staff sergeant and a corporal, and four teams made up of a sergeant and a corporal. These teams are designed and optimized to execute precision fires and scouting missions for the battalion. The base unit of employment is one team of two Marines, which could conduct independent operations for short periods, combine teams for longer more complex missions, or directly support companies. (See Figure 3.)

Strengths. There are numerous advantages to trading current infantry battalion structure for two enfantry companies and one RSS company:

1. Enhanced performance. These units will execute current T&R tasks to highest standards and effectiveness, 1.e., near 100 percent reliability and proficiency.

2. Versatile. These units will be able to expand the capabilities of battalions by taking on new advanced T&R tasks, i.e., ability to execute (CLT) distributed operations, use of advanced communications equipment, joint terminal attack controllers with an ANGLICOlite capability, ability to execute ‘ long range” patrols and raids, and enhanced medical capacity.

3- Trusted. With virtually a guarantee of performance, the national leadership and combatant commanders would be more willing to select these units, e.g., they would be trusted to carry out missions from L-Class ships that currently warrant calling in Special Operations Command units.

4. Flexible. E3 units are leadership heavy and would be able to support advisor training teams taskings without stripping the key billets of an entire battalion. These units could partner to advise and train and/or to conduct combine operations with allies and partner nations.

5. Expandable. Each enfantry company could scale up to a full regular rifle company. The NCOs, SNCOs, and officers are hard to scale up quickly, but they would be in place. The junior Marines could scale up relatively quickly and combine to establish a standard table of organization and equipment rifle company.

6. Interoperable. E3 units would aim to be the preferred partner of the Raiders and other Special Operations Command units.

7. Candidates Pools. There is an opportunity for the Marine Corps to establish an in-depth candidates pool, which would feed recon and Raider units without breaking the rest of the Service (specifically recon) by logically progressing from a rifle company, to an enfantry company, to recon battalion, and to the Raiders. Raiders could cycle back to spread the knowledge and experience to the Service’s operational forces. (See Figure 4.)

8. Freeing. The E3 concept will likely free recon from some tasks, allowing them to focus on missions from higher headquarters, and having the depth to fully achieve and/or increasing standards and capabilities.

Challenges. There are few disadvantages to the E3 concept:

1. Higher cost to retain more secondterm and career Marines, i.e., NCOs, SNCOs, and officers-captains and majors. (See Figures 5 and 6.) Time will be needed to grade shape the force.

2. The Service is only allowed 21,000 officers by law. Of those, 17,500 are available to support table of organization requirements after taking into account trainees, transients, patients, and prisoners costs. Of those 17,000 that support the Authorized Strength Report (ASR), 16,400 are available to actually fill unit billets. This would cause a shortage about 168 officers, which means total officer structure would need to be reallocated or increased.

3- There would be a higher cost to arm, train, and equip the force over those required for entry-level training and standard battalion deployment work ups.

4. The E3 concept also will cause grade shaping for recon and Raider Marines.

Other MOSs

E3 infantry battalions, recon and Raiders units, would benefit from individual and unit E3 capabilities in other communities. Other communities would execute current T&R tasks to a higher standard and possibly add some newT&R tasks. These would include: engineers, intelligence analysis, logistics teams, communication teams, and unmanned aircraft (VMM) squadrons. Imagine a VMM squadron where 30 percent of its pilots and air crews are made up of highly exceptional pilots, also known as “good sticks.” These majors and SNCOs would focus on flying.

Equipment

An equipment (technological) solution is often the first option used to solve a challenge. This article relegates equipment third behind people and ideas, but it’s still a key force multiplier. To ensure performance in urban littoral operations requires trained and certified Marines, cutting edge equipment, LClass ships, and possibly non-standard shipping.

Naval power projection and protection. The Marine Corps and the Navy have a unique capability which needs an antimissile and anti-ballistic missile ship protection system. A similar subsurface threat protection system is also needed. A realistic solution needs to be found to continue to field a credible capability.

Urban communications. Communications is the number one challenge. It’s the communications device that allows a Marine on the ground to call in the vast resources to locally overwhelm the enemy. It enables Marines to strike the enemy, conduct command and control (C2), resupply, and call for life saving support. Troops on the ground need internal communications for every Marine. PDAs (personal digital assistant) will provide better situational awareness, mapping, 3D mapping, and a way to quickly pass orders/frag orders. A way is needed to overcome the communications dead spots that are inherent in a dense urban environment and also overcome the likely use of local jamming and hacking. A communications system is needed that is locally strong enough to overcome jamming and provide multiple avenues or relays for messages to be sent around urban obstructions. Imagine an airborne network made up of numerous small independent unmanned aircraft vehicles/systems that are link into a system that allow for continuous coverage and service by allowing them to seamlessly integrate and self-repair, as individual vehicles/systems need maintenance or are lost.

Unmanned systems. Unmanned systems will be needed to support the six warfighting functions. The urban environment is very Marine intensive. Unmanned systems, large and small, both ground and air (fixed- and rotary-wing) will be needed to conduct: 1. reconnaissance, 2. logistical resupply, 3- communications and relay platform, and 4. strike/ground attack. The wave of the future for logistics is unmanned aircraft systems. They have great advantages for ship-to-shore logistics and are 100 percent safe to transport supplies into and through an urban environment. GPS guided, parachute, aerial resupply systems could also be an option. Imagine an enfantry section using “pull logistics” and directly receiving a night delivery of batteries, ammo, water, ammo, and MREs directly from a quad-copter.

Fires. The ability to deliver small diameter munitions, with high accuracy, is essential to the landing force for engagement winning or lifesaving support while limiting collateral damage and the political side effects. The landing force will likely be distributed and outnumbered. Superior CLT (GCE) precision fires (munitions) capability will be the key force multiplier to ensure operational and tactical execution.

The landing force will also require munitions capable of targeting rooms and floors within buildings. Enhanced M203 ammunition options, soft launch rockets, and an improved system for the 0351 community will greatly improve the capability of the landing force. This includes an overpressure thermobaric or novel explosive rounds.

Urban mobility. The landing force will need systems to ingress, transit, and egress the urban environment. To connect to the seabase, non-standard, and L-Class shipping will require a system like the ultra-heavy lift amphibious connector. A connector is needed to land on narrow beaches were LCACs cannot land. An innovative solution is needed to tackle sea walls. Think of Inchon and its sea walls, which are now commonplace. Protection will need to be balanced with weight, speed, amphibious ability, and overall efficiently. The same will be needed while transiting the urban environment. Innovation is needed with everything from improved armored vehicles and fast attack vehicle options to urban terrain climbing kits.

Other technology.

* Imagine eye protection integrated with a heads-up display and a camera mounted weapons system that would allow the Marine to shoot around corners and capture images or video and upload them to their squad, platoon, or company. With the use of night vision goggles becoming wide spread, the Marine Corps needs to add a different technology. Thermal optics coupled with smoke may be a way to maintain an advantage.

* Developing an airborne medical module would greatly improve performance and enable longer range missions. Heart defibrillators are everywhere, why not build a complete medical system that could be loaded into an aircraft? Mission risk would be lower by providing casualty stabilization. Crews and corpsman would need training.

* Regarding the invisible electronic battlefield, Marines should look for ways to enable non-technical specialists to hack into local networks. Think network hacking kit (NHK). This capability would allow non-technicians to locally setup a reach back capability, which could unleash 100s of cyber Marines, while at the same time providing network protection to stop attacks by adversaries who attempt to hack into the communications network and taking over unmanned logistic and weapons systems.

Other challenges. At the end of the “Ideas” section, this article covered the higher cost to retain second term and career Marines, the challenges with officer structure, and the cost to arm, train, and equip E3 units. In addition to those challenges, some of the proposals in the equipment section would be costly and require extensive maintenance. It would also open the force up to risk of critical failure regarding integrated C2 communications; personal communications, data, and optics; as well as the complex problem of making a fleet of unmanned vehicles/systems and ground systems function to support reconnaissance, logistics, communications, and strike/ground attack. To ensure capability, technology integration needs to be balanced with non-electronic backups, e.g., GPS vs. maps and compasses.

Conclusion

The urban littoral environment is the most complex terrain in which to conduct military operations. The best way to improve Marine Corps performance and operational capabilities is to adopt an E3 Concept by adjusting ^5 percent of our total force structure to build concentrated pools of experienced Marines by forming units made up of NCOs, SNCOs, and officers. This will result in an overwhelming tactical advantage by raising the bar on standards, capability, and performance, and it does so in a practical, cost-effective fashion. There is one thing that impresses congressional members, and that one thing is performance, which means the Marine Corps will go in, win, and then come home alive. An E3 concept will ensure performance.