by LtCol David W. Baas

In guidance preceding the 2025 planning effort, the Commandant offered a severe warning: “Failure to change the shape and form of the Service will condemn it to irrelevance.”1

The 2025 effort has imparted change-such as structure and naming conventions-under the umbrella of broad Service concept documents. However, the clear vision and detail required for unified evolution of the major subordinate elements of the MAGTF toward a cohesive, modern force-one that adapts to the future operating environment (FOE) while remaining true to our maneuver warfare roots-has not followed. As subordinate plans develop, they often lack the clarity of vision and practical detail required to drive unity of effort across disparate occupational fields.

The GCE needs a clear vision-the “ends” to unify force development efforts. This article intends to add to the dialogue around ívhat must change about the GCE and why. In considering these questions, we must also recognize an important constant: the unchanging “nature” of ground conflict and the role of the GCE within the MAGTF. A clear vision informs force development efforts of other MAGTF elements-just as a dulled vision provides little practical insight and leaves room for wasted or uncoordinated effort and expense. As the 2025 effort is effectively into execution, our planning horizon must expand. This vision considers our unchanging nature and what is presupposed of the FOE to arrive at a series of mutually supporting conditions: the “ends” for a 2035 GCE to meet the likely missions, address the premier problems, and remain relevant to the MAGTF and the joint force.

The Unchanging Nature of Ground Conflict and the GCE

As we assess the implications of the FOE, it is clear the character of the GCE must adapt and evolve. However, any changes must enhance, not compromise, our ability to thrive within the unchanging nature of ground conflict. The GCE serves as the “base” unit within a MAGTF and must be an expert practitioner of maneuver warfare. In concert with the other MAGTF elements, the GCE must consistently take action to generate and exploit a relative advantage over the adversary as a means of effectively accomplishing the mission.2 The unchanging goal in conflict is “to diminish enemy freedom of action while improving our own-so the enemy cannot cope with events as they unfold, while we can.”3

The GCE interacts with populations, terrain, and conflict, across the spectrum in a direct and personal manner. It must embody recognized, time-tested fundamentals of ground conflict:^

* Maintaining situational awareness.

* Exploit known enemy gaps.

* Control key terrain.

* Dictate the tempo of operations.

* Neutralize the enemy’s ability to react.

* Maintain momentum.

* Act quickly.

* Exploit success.

* Maintain flexibility.

* Be audacious.

* Provide for the security of the force.

Any change must enhance these fundamentals to retain our ability to generate a faster relative tempo, seek out and shatter an adversary’s cohesion, and destroy their “ability to fight as an effective, coordinated whole.”5

The Projected Future Operating Environment

With the unchanging nature of ground conflict reaffirmed, an understanding of key trends presupposed of the FOE provides the “why” for evolving the character of the GCE. The following trends incorporate common aspects and challenges from multiple joint and Service documents for the 2035 timeframe.6 They should not be viewed in isolation, as the GCE will likely be required to operate within and across several at any given time.7

Complex conflict in complex environments. Adversaries have learned to leverage complex environments-those with physical and cognitive stressors that also limit the effectiveness of technology- to their advantage, reducing any fight to infantry alone.8 This includes jungle, mountain, cold weather, and the urban megacity. Rapid growth of megacities coupled with demographic shifts will stress traditional social norms, resources, and infrastructure-setting the stage for imbalance, unrest, and potential conflict.9 The “three-block” war is likely to evolve to a “three-floor war” where actions occur among an intermingling of combatants and non-combatants in high-rise buildings within one block of a crowded urban littoral slum.10 Conflict will be a “multi-agency fight across multiple lines,” spanning sectarian, ethnic, health, or other issues.11 Destruction from extreme weather, natural disasters, desertification, resource shortages, and migration of distressed populations all increase the likelihood that water, food, and energy issues will accompany regional instability and crisis.12

Increasingly contested maritime domains. The increasing “congested, contested, and competitive” character of the maritime global commons will revitalize the importance of the GCE in naval actions to ensure freedom of navigation and commerce.13 This pits the value and utility of amphibious forces against the proliferation of state and non-state anti-access and area denial capabilities. Additionally, new areas of contention may emerge-such as control of Arctic waters. ^

Technology proliferation and evolution of employment. From the global commons to “high tech warfare at knifepoint range”13 in an urban three-floor war, technology proliferation must be leveraged to enable and streamline- not overburden-the ability of GCE echelons to sustain a relative advantage over adversaries. Standing efforts to evolve situational awareness, precision lethality, and force protection are joined by signature detection/management, manned/unmanned teaming (MUM-T), preventative health and expeditionary medicine, and threats from proliferated chemical/biological agents. Signature is an area of particular urgency. To adapt, ground forces must manage signatures across all aspects of contact, from visual to electromagnetic-as well as understand and be able to exploit the signatures of an enemy.

Information as a weapon. In balance with signature management, the GCE must become more effective and efficient at leveraging information networks to establish conditions, achieve specific objectives, or create and exploit opportunities. This begins with ensuring continuity of our networks through redundancy and defenses “capable of reacting in a highly dynamic environment.” 16 With a protective foundation, global network “connectedness” offers leverage points to observe, orient, and find gaps through which to act- “leaping over” traditional military force to directly influence an adversary via effects on select leadership, audiences, or infrastructure.17 The speed and depth of human connectivity offers a specific challenge to turn the “rallying power of information connectedness”18 from a historically counterproductive force to one that actively supports security objectives.

The 2035 GCE

To establish the desired clear vision and end state, we add consideration of the likely missions the GCE will face in 2035, across three categories:1920

* Military engagement, security cooperation, and deterrence.

* Support to extended deterrence, freedom of navigation, and global commons stabilization.

* Military support to foreign partners.

* Crisis response and limited contingency operations.

* Support to Department of State (DOS; Diplomatic Post Reinforcement, non-combatant evacuation operations).

* Support to stabilization (blocking operations/exclusion zones, punitive raids).

* Global commons defense.

* Large-scale combat operations.

* Global maneuver and seizure (power projection to defend interests, seize key terrain/objectives).

* Counterinsurgency and peace enforcement.

To be successful across these missions in the FOE, the 2035 GCE must adapt its character without compromising its nature. Toward this balance, two premier problems must be addressed:

* Evolve intelligence and command and control (C2) to support situational awareness (observe, orient) in complex conflict and terrain, without provoking cognitive overload of small unit leaders, to provide the foundation upon which the battle for relative tempo is won.

* Leverage situational awareness into bold, relentless action through a complementary evolution in maneuver, fires, force protection, and logistics to overcome a sophisticated multi-domain defense-in-depth.

Given our nature, FOE, missions, and problems to be solved, the GCE must focus force development actions toward ten specific conditions that collectively define an end state for 2035 (see Figure 1).

This vision-nine initial complementary conditions enabling a tenth and final condition-İs illustrated via the following three vignettes.

Vignette #1: Support to DOS-Company in Sub-Saharan Africa. Migrants fleeing food and water shortages stress the aging infrastructure of a developing capital city, creating unrest. As outlying camps develop into slums, the population grows to over ten million residents, with migrants increasingly pitted against traditional residents. Clashes over resources, law enforcement, and wages deteriorate the situation. Despite international attention, western nations do not intervene- angering migrants. Extremist groups leverage information networks to import and distribute ideology, gaining influence and radicalizing individuals toward employing violence. As the U.S. Embassy becomes a focal point for protest, the DOS assesses the threat as requiring rapid additional military support.

An expeditionary landing team (ELT), comprised of a rifle company and enablers, reinforces the post while its parent battalion landing team and MEU postures to conduct foreign humanitarian assistance and/ or non-combatant evacuation operations if required. Inserting under cover of darkness, the ELT assumes a defensive posture around two facilities separated by several city blocks. Compatible communications allow the ELT to quickly connect and contribute to overall situational awareness, leveraging intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance to assess, identify, and track key instigators of violence. Patrolling and numerous disposable sensors expand the situational awareness network as the fire support team (FiST) works with MEU informationrelated capability (IRC) enablers to disrupt the adversary’s ability to rally protests, isolate them from external information, and discredit/distance them from the population. Resupply is received via unmanned logistics systems (ULS) with smaller ULS distributing between the separate facilities. Preventative measures protect Marines from disease while corpsman are able to stabilize and treat serious injuries- providing more time for evacuation or avoiding the need at all.

Condition 1 (situational awareness). Accurate situational awareness is the foundation upon which we generate and sustain a relative advantage over an adversary. Enhancing this begins at the small unit level (company and below) by combining unit leaders capable of understanding a complex, rapidly changing environment with a light, rugged, and simple common tactical picture (CTP) interface. Multiple wargames reinforced the need to provide a CTP down to the lowest echelon possible.21 However, access to excessive and untailored data risks cognitive overload. The interface must enhance the leader’s ability to understand the environment-enabling rapid assessment of situations and the potential to “see the enemy first.”22 Complementary development of disposable low-signature sensors to seed areas will expand the network of information that can be collected, filtered, and interpreted. Consistent with our maneuver warfare foundation, the interface should focus on the small unit first and then expand to higher echelons. Implementing, enhancing, and safeguarding a layered situational awareness network is key toward addressing larger issues such as countering adversary long-range precision fires.

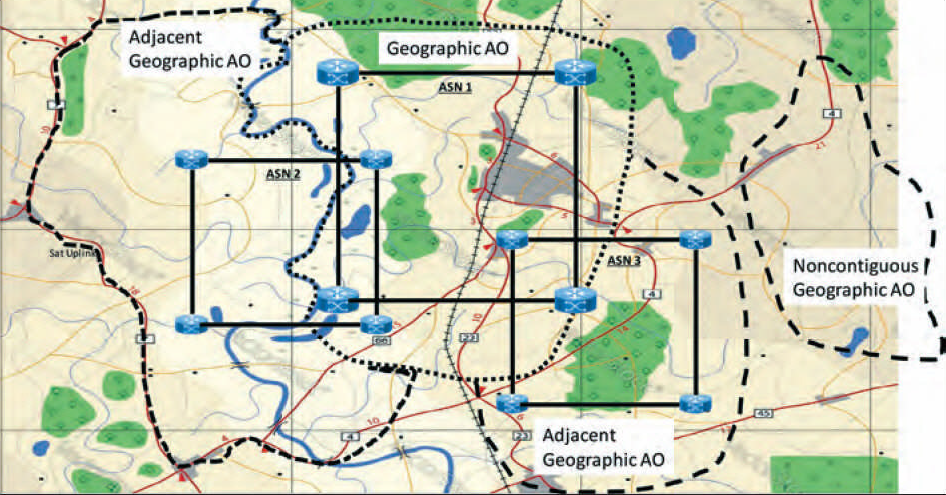

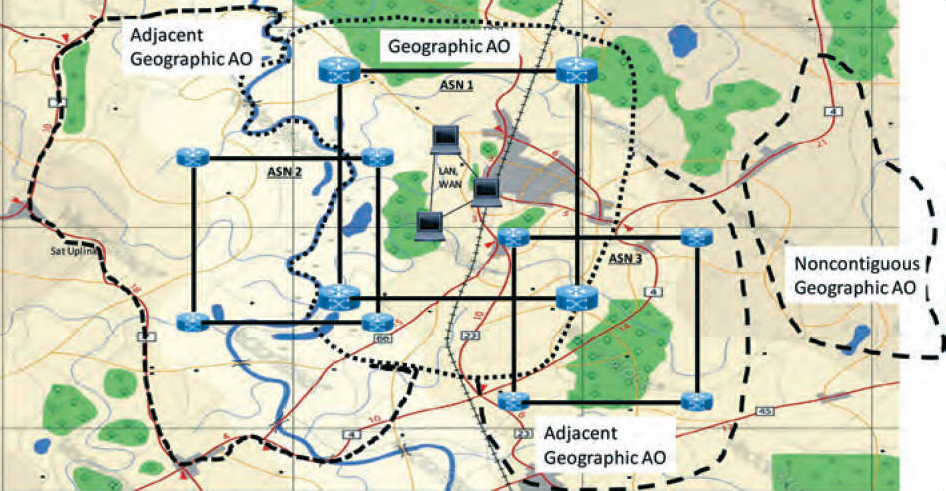

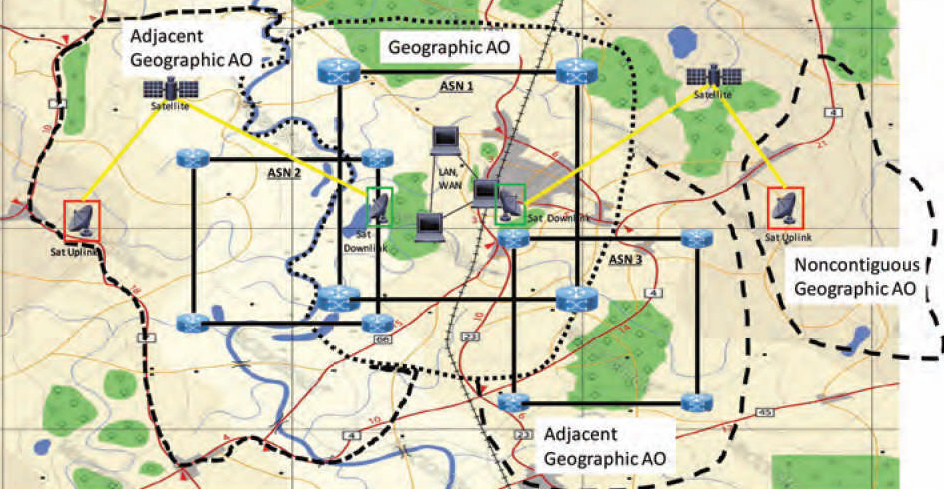

Condition 2 (interoperable communications). Provided the best situational awareness, gaps and inefficiencies in communications degrade our ability to act quickly-allowing the adversary opportunities to recover or preempt our action. Again, wargames point to the need for:

* CTP integration for intelligence, information warfare, fires, and C2 information.23

* Extended range/redundancy in complex terrain by leveraging civilian infrastructure, combat/tactical vehicles, and the use of unmanned (ground/air) communications nodes.24 23

* Interoperability with aircraft, naval forces (ships/landing craft), special operations forces, and DOS security personnel.

* Adjustable electromagnetic signature to manage risk in varying environments.

This condition should also focus at the small unit level first, then expand upward to higher echelons.

Condition 3 (small unit employment of IRC). Rules of engagement or other circumstances may limit our ability to gain advantage over an adversary through physical maneuver or fires until an overt hostile act is committed. IRC employment in this vignette to exploit known gaps and neutralize the adversary’s ability to react is critical for mission success. We must refine the company FiST to provide complementary kinetic/ non-kinetic capabilities in support of maneuver. While IRC may best be provided through missi on-tailored enabler packages, the FiST must have the knowledge, experience, and access to the authorities and equipment to produce the most appropriate effect for the situation.

Condition 4 (sustainment of distributed small units). Meeting this condition encompasses both a reduction in the amount of required sustainment and enhanced means of distribution. In balance with maintaining small unit capabilities, required sustainment may be reduced but never eliminated. Distribution of sustainment by ULS provides promise, with different sizes in a modified hub-and-spoke system from the seabase down to the small unit.26

Condition 5 (enhanced small unit medical coverage). Increasing operating distances and degraded health environments require enhancing preventative and field medical care. Urbanization and proliferation of disease adds to the difficulty of preventative measures as GCE personnel are called upon to operate in “overcrowded urban environments where human waste, garbage, and insects combine with a lack of sanitation,” potentially requiring regional specialization for units to deploy rapidly.27 Once deployed, the traditional concentration of medical capability above the company level necessitates enhancing the ability of line corpsman to provide the “gift of time” through casualty stabilization at or near the point of injury.28 29 Additionally, leveraging ULS to transport medical supplies and evacuate casualties holds significant potential.

Vignette #2: Global Commons Stabilization/Defense-Battalion in South China Sea. Following increasing congestion and competition over resources and territorial rights, adversarial nation threats to restrict freedom of navigation have brought international sanctions and intervention to avoid large-scale conflict. In partnership with allies, an expeditionary advanced base (EAB) is established by a special purpose MAGTF centered on an infantry battalion to retain the base and conduct stabilization and defensive activities in support of freedom of navigation. The battalion is organized to project company ELTs with small boats, assault support aviation, amphibious combat vehicles (with surface connectors), ISR and IRC enablers, and long-range precision fires. Should conditions escalate, the battalion is equipped for interoperability with joint forces that could be deployed to the area.

A punitive raid is directed to counter adversary emplacement of an anti-ship cruise missile system in a critical international shipping area. Two littoral combat ships and a submarine support an ELT raid via small boats. The fire support coordination center aligns IRCs to isolate the target while concurrently employing multi-signature decoys, sensor swarms, and long-range fires to identify and exploit adversary gaps and protect the ELT-maintaining the initiative throughout the operation. Two additional ELTs posture (one air assault, one in amphibious combat vehicles aboard connectors) as an alternate raid force or a means to reinforce.

Condition 6 (reconnaissance by force: sensor swarms and decoys). Achieving a relative advantage over a sophisticated adversary requires GCE echelons to gain and maintain contact while simultaneously reducing or masking their own signature. In balance with our ISR/C2 demands, we will likely only manage signature-never eliminate it. Therefore, we must work, as we gain and maintain contact, to degrade the effectiveness of the enemy’s decision cycle through multi-signature decoys and cheap, disposable sensor swarms that seek to activate and overwhelm adversary ISR and strike networks.30 This low risk reconnaissance by force will provide gains in information and elicit adversary reactions-exposing gaps through which we can maneuver or enable us to find, fix, and attack high pay-off targets (like long-range fires).

Condition 7 (expeditionary advanced bases and punitive raids). EABs offer a vital role to the GCE-to control key terrain and facilitate access and maneuver, they offer persistent presence while freeing up and reducing risk to valuable naval shipping.31 Raids offer a limited response to hostile disruptions of the commons. Non-traditional naval assets-like an littoral combat ship or submarine-can support audacious low signature maneuver under an umbrella of IRC and kinetic fire support from the EAB. Alternate means of achieving or reinforcing the objective (air assault, heavier surface forces) retains flexibility as circumstances develop.

Condition 8 (enhanced fires and air defense). The GCE must extend the range of kinetic fires to support dispersed and distributed units, fully integrate employment of IRCs into fire support/coordination cells, and contribute to countering adversary air/ unmanned systems. We must refocus on the nature of fires in support of maneuver, employed to destroy when necessary, but primarily to disrupt/obscure and neutralize the enemy’s ability to react effectively to our tempo. Additionally, efforts toward efficient small unit targeting, counter longrange precision fires, and fire support de-confliction within a complex urban environment are needed.32

Vignette #3*’ Global Maneuver and Seizure-Regiment/Division in the Baltics. Following a popular uprising in the eastern portion of a Baltic NATO nation, the initial allied, response pushed through proxy forces to reveal multiple adversary battalion tactical groups (BTG). A Marine division is deployed to destroy the adversarial forces and restore territorial integrity in the dead of winter.

The division employs regimental combat teams (RCTs) conducting complementary infiltration and exploitation operations in the cold weather to seize and maintain a speed/ tempo advantage in relation to the BTG-oriented defense in depth. Decentralized and dispersed action by light and mobile forward infiltration units and heavier mechanized exploitation units enable each RCT to deny enemy effective situational awareness, identify and exploit gaps, and by-pass/ hand-off urban areas to allied/hostnation forces. Sustaining a higher relative tempo and speed keeps attacking echelons ahead of threat long-range fires and allows the RCTs to break up each BTG and neutralize/destroy it at will.

Condition 9 (equip and train for specialized environments). The GCE must equip and train itself to operate across all environments. Adversaries will exploit conditions (jungle, mountain, cold weather, etc.)-as well as chemical or biological weapons-to disrupt our tempo and gain an advantage. While chemical and biological conditions apply uniformly, attempts to train and equip every GCE formation equally for every environment is likely unrealistic. Ensuring readiness may require unit specialization to effectively leverage limited resources.

Condition 10 (modern breakthrough battle). The integration of the first nine conditions culminates to produce this tenth and final condition: a cohesive GCE-base unit of the MAGTF-capable of modern breakthrough battle. Our battalions, regiments, and divisions must be the foremost practitioners of maneuver warfare to counter a sophisticated adversary’s integration of technology within a multi-domain defense in depth. Dispersed tactical maneuver must still behave “like water,” infiltrating to seek out weaknesses via multiple thrusts by small units, decoys, and sensors. In combination with fires, these thrusts disorient/disrupt defenders thereby gaining and maintaining the initiative while slowing the enemy’s ability to react. When a gap is identified or created, it must be exploited ruthlessly by subsequent echelons of strength to “unhinge the front” and bring about the collapse of the enemy’s cohesion and ability to resist.33 A 2035 RCT organized for breakthrough battle:

* One infiltration battalion combining sensor swarms, multi-signature decoys, and maneuver companies to seek and aggressively develop gaps through:

* Light MUM-T vehicles to enhance air-transportable low-signature mobility.

ш Longer-range anti-armor weapons.3^

* C2 tools that enable CTP, targeting, IRC enablers, and signature management.

* Two exploitation battalions that maximize mobility, protection, and direct fire/shock effect by mechanizing with armor and managing their signature with regimental IRC support.

* Enhanced fires and air defense to neutralize high payoff targets, disrupt and obscure in support of maneuver, provide counter-battery fires, and counter air/unmanned systems.

* Reconnaissance contributing to situational awareness and deception with decoys and unmanned vehicles operating “like traditional cavalry” to demand/distract enemy attention.33

Conclusion

Success begins for the 2035 GCE with the battle for situational awareness. Our ability to gain and maintain contact while selectively masking our own signature remains essential to reducing the effectiveness of enemy decisions and actions. Illustrative of a sophisticated enemy, the BTG’s primary advantage relies on an ability to find and target slow-moving formations, command posts, or other nodes emanating an electronic signature with long-range systems.36 Building on an unchanging nature in ground conflict and maneuver warfare, we must enhance and evolve the character of our echelons across the conditions described above to produce a 2035 GCE that will outpace our enemy, find and exploit gaps, and close with and destroy through bold and relentless action.