by Cdr Terry C. Pierce, USN

Operational Maneuver From the Sea (OMFTS) is a concept for combining the maneuver of Navy forces and the maneuver of the Marine air-ground task force (MAGTF) to produce a seamless operation between actions at sea and actions on land. Applying the principles of maneuver warfare to littoral battles and operations, the Navy and Marine Corps hold that this concept can exploit the extraordinary operational mobility offered by naval expeditionary forces without loss of momentum during the transition from sea to shore. Our ability to achieve this improved power projection capability, however, requires that we possess a seamless command and control capability from sea to land. This is a difficult proposition, one that may be solved only after a close examination of the maneuver warfare term, “main effort.”

The naval expeditionary force (NEF) is a cohesive, integrated, task-organized Navy and Marine force designed to control and dominate a designated sea-air-land battlespace. The tools of NEF power projection include missiles, shells, bombs, bullets, and bayonets. Of all the NEF’s power projection capabilities, the most decisive tool is the amphibious operation. Only a MAGTF can introduce troops into hostile territory from the sea, culminating a naval operation or enabling a continental one.

OMFTS refers to the means by which the Navy and Marine Corps bring a MAGTF from the sea to bear against selected enemy vulnerabilities and gaps. Like maneuver warfare, OMFTS is a philosophy, a way of approaching a particular set of problems. In short, it is an effort to remove the seam at the highwater mark that has traditionally separated naval and land combat. In this new approach, sea and land are both used as maneuver space for a single fluid operation.

Admittedly, our doctrine writers have yet to describe the command philosophy that is necessary for the NEF to fight as a maneuver force and project power ashore. This may take time as the Navy is just beginning to thoroughly understand the Marine Corps concept of maneuver warfare. Fortunately, however, the tenets and terms of maneuver warfare are generally interchangeable with those used in OMFTS. This fact, I would argue, means that the NEF’s philosophy of command should be the same as the MAGTF’s philosophy of command.

In other words, the Marine Corps not only brings a wealth of ideas from maneuver warfare to OMFTS, but also its philosophy enriches and complements the Navy’s notion of OMFTS, thus making both more effective. Since the maneuver warfare concept of main effort is an important tool for providing unity of effort for the MAGTF commander, it will also be an important tool for providing unity of effort for the NEF commander.

In fact, of all the key ideas of maneuver warfare, main effort is perhaps the most important. Unfortunately, however, this concept means something different to the Navy and Marine Corps. For the Marine Corps, the term “main effort” includes supported unit. For the Navy, it does not. Yet, when main effort includes the concept of supported unit, it allows us to mesh the Navy’s composite warfare commander (CWC) concept with amphibious doctrine to achieve a single seamless operation from commitment of the NEF through success ashore.

Main Effort

Modern maneuver warfare theory, as explained in three recently published Marine Corps Fleet Marine Force manuals, uses the concept of main effort to put maneuver warfare into practice (see FMFM 1, Warfighting; FMFM 1-1. Campaigning; and FMFM1-3, Tactics). The main effort is defined as the unit that the commander believes will enable him to achieve a favorable decision. This unit has the most important task to be accomplished, the one on which the overall success of an operation will hinge.

Once the commander designates a unit as the main effort, he then concentrates his support and combat power on it so as to ensure quick success. Likewise, all other units work to support the main effort, even in the absence of specific directions. Thus, through the main effort, the commander creates a unity of effort by providing a focus that each subordinate commander uses to link his actions to the actions of those around him. As a result, throughout the force, main effort ties together a multitude of independent efforts ensuring that they relate to one another.

Conversely, without a main effort, combat quickly breaks down into a multitude of independent efforts, each divergent from one another. So the value of specifying main effort is that it allows subordinate commanders to seize opportunities as they arise during combat while still supporting operational goals.

The commander designates only one main effort at any one time. In other words, in any operation, only one portion of a particular organization is designated to strike the decisive blow. Considering the safety of his entire force and the level of acceptable risk, the commander stakes the success of the entire action on the performance of his main effort.

Calling it effort principal, the French were the first to coin the phrase of main effort. Applying main effort primarily at the corps level, the French saw its significance as a course or direction of effort decided on before an attack and afterward seldom changed. The Germans, on the other hand, placed a much different emphasis on the concept. Calling it Schwerpunkt, they saw it applying not only to the corps, but also spanning the entire chain of command to include small infantry units at the tactical level.

By 1918, Schwerpunkt was becoming more sophisticated and differed dramatically from the French concept of main effort. Indeed, the Germans had developed an attack based on locating an enemy’s critical vulnerability and forming a main effort to exploit it while their other forces supported that effort. Moreover, their introduction of the idea that a force could shift its main effort during an attack was of critical importance. Thus, in the course of the attack, as the situation changed, the commander could shift his main effort and redirect the weight of his combat power in the manner that made the most sense and offered the greatest chance of success. In this way, a commander was able to exploit success and prevent failure.

The German’ concept of supporting effort is also important to us. The means by which supporting units assist the main effort is often covered in explicit orders. In the absence of these, all other units must seek and do all they can to assist the main effort. In most cases, this can be accomplished by aggressive action. The more aggressive the action of supporting units, the less will be the ability of the enemy to resist or even identify the main effort. For example, during the German blitzkrieg of May 1940, panzer group commander Gen Paul L.E. von Kleist, overall panzer commander for the campaign, designated Gen Heinz Guderian’s Panzer Corps as the main effort for the attack through Sedan to the French coastline. Similarly, Kleist designated Gen Hermann Hoth’s 15th Panzer Corps as the supporting effort. Consisting of 5th Panzer Division and Gen Erwin Rommel’s 7th Panzer Division, Gen Hoth’s Panzer Corps, as a supporting effort, was to protect the right flank of Guderian against an attack by powerful Allied forces that would be located farther north in Belgium.

Although Guderian received most of the Luftwaffe ground attack support because he was the campaign’s main effort, Rommel, who was Hoth’s main effort for the supporting attack, pushed his division so successfully that it not only matched, but at times outpaced Guderian’s. The result of Rommel’s supporting spearhead was that he so perplexed the French command as to which penetration, Rommel’s or Guderian’s, was the main thrust that he successfully created a distraction that diverted French forces from Guderian’s main effort.

Thus, the continuous designation of the main effort from above, throughout the chain of command, is an inherent part of this concept. In other words, as soon as the commander designates a specific unit as the main effort, all subordinate commanders, whether they are the main or supporting effort, will; in turn, designate their main effort. And the process continues on down the chain of command. So we have the concept of a main effort within another main or supporting effort. Thus, commanders at all levels designate a main effort, focus resources to support it, and shift it rapidly as the attack unfolds if another effort appears more promising.

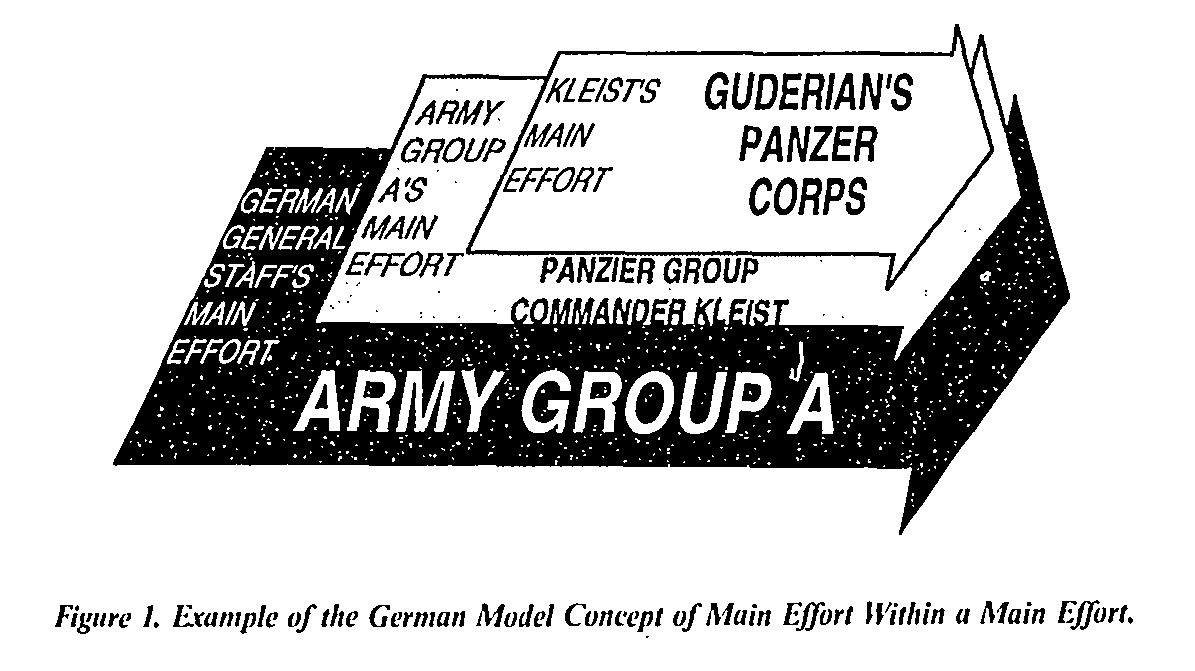

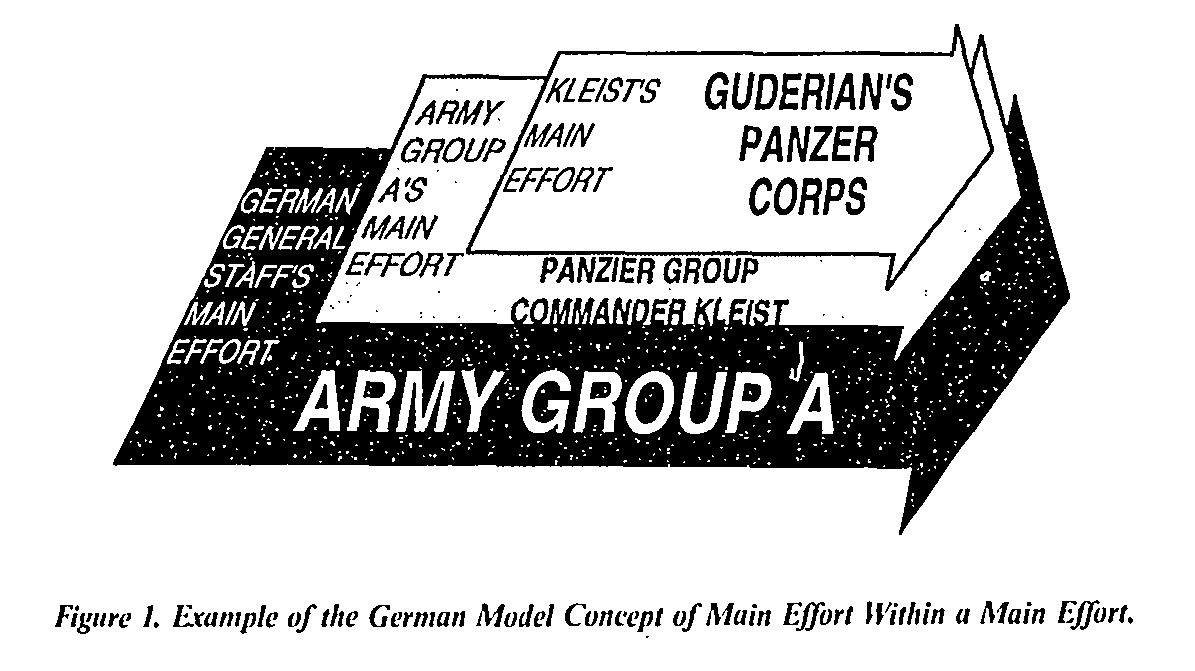

An example of this concept is again contained within the German blitzkrieg into France in May 1940. The German General Staff made Army Group A its main effort and Army Group B and C its supporting elements. Group A’s commander. Gen Gerd von Rundstedt, in turn, made Kleist’s Panzer Group his main effort. Kleist’s Panzer Group was made up of Reinhardt’s Panzer Corps (the 6th and 8th Panzer Divisions), and Guderian’s Panzer Corps (1st, 2d, and 10th Panzer Divisions). Kleist then designated Guderian as his main effort (see Figure 1).

Main Effort and Operational Maneuver From The Sea

OMFTS relies upon the naval expeditionary force (NEF) commander exercising centralized planning and decentralized leadership. It is he who. considering the situation on both the sea and the land, will conceive the operation, express his intent and concept of operations in the form of mission-type orders, provide unity of effort by determining his main effort, and respond, if necessary, to changing situations by shifting the main effort.

The tool that will enable this flexibility of main effort within the NEF is the composite warfare concept. Without using maneuver warfare terminology, this command and control concept has used maneuver warfare tenets for years. It employs commander’s intent, mission-type orders, and decentralized execution-all mainstays of maneuver warfare. Its shortfall, however, at least with regard to OMFTS. is that it is functional in design. In other words, its commanders are neither supported nor supporting, they simply perform the desired function. To take this one step further, we must add the concept of main effort-a concept that includes supported and supporting.

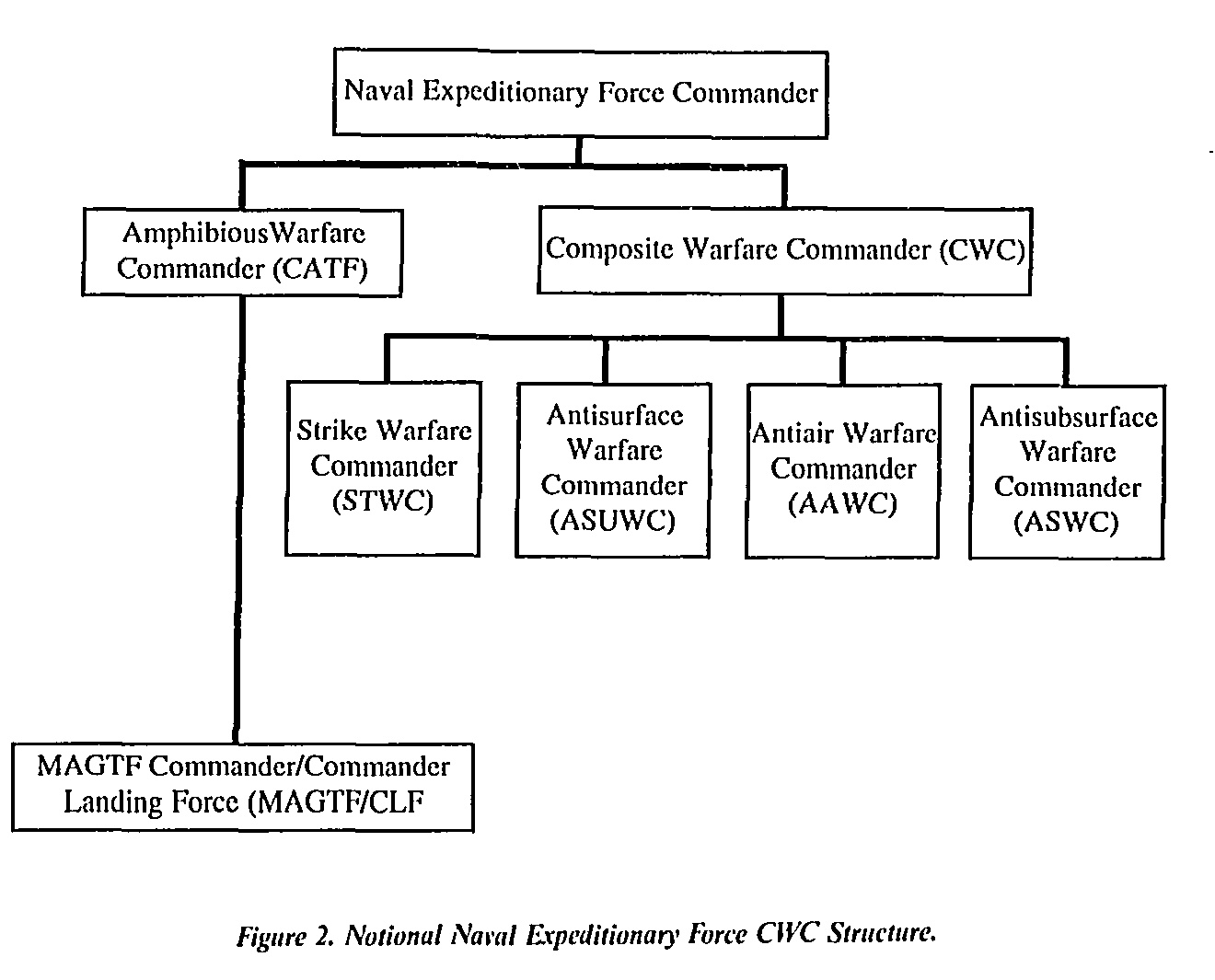

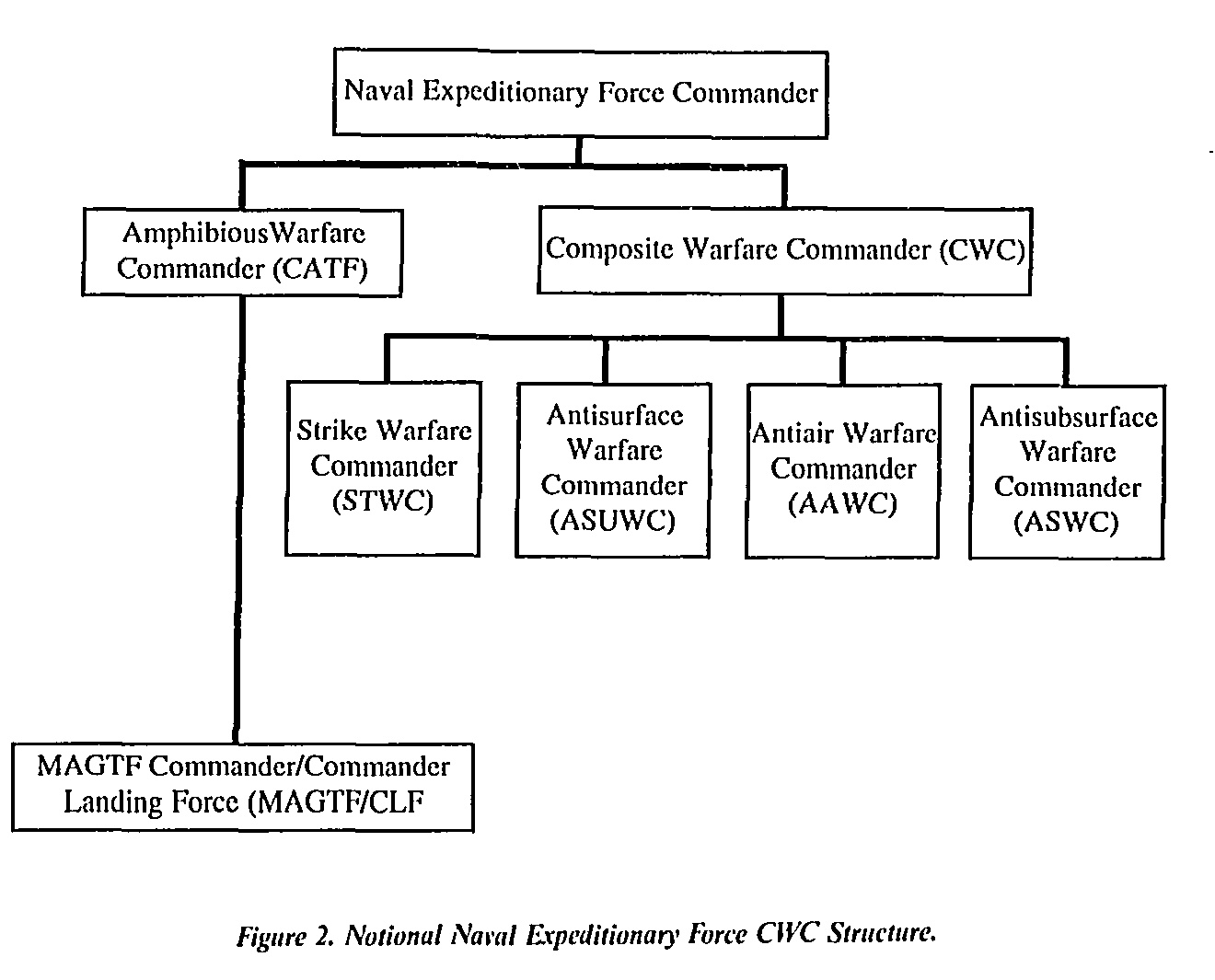

The commander of the NEF is in command of a variety of subordinate leaders including the amphibious warfare commander (AWC) and MAGTF commander. The important point to remember is that depending on the situation, the NEF commander can designate any subordinate commander as his main effort. He may then shift the main effort to another commander, in accordance with his plan and the developing campaign. For example, during the period when the NEF commander is trying to achieve battlespace dominance and his most immediate threat is small, fast enemy patrol boats, he may initially designate his antisurface warfare commander (ASUWC) as the main effort. Of course, the remaining warfare commanders are also supporting efforts (see Figure 2).

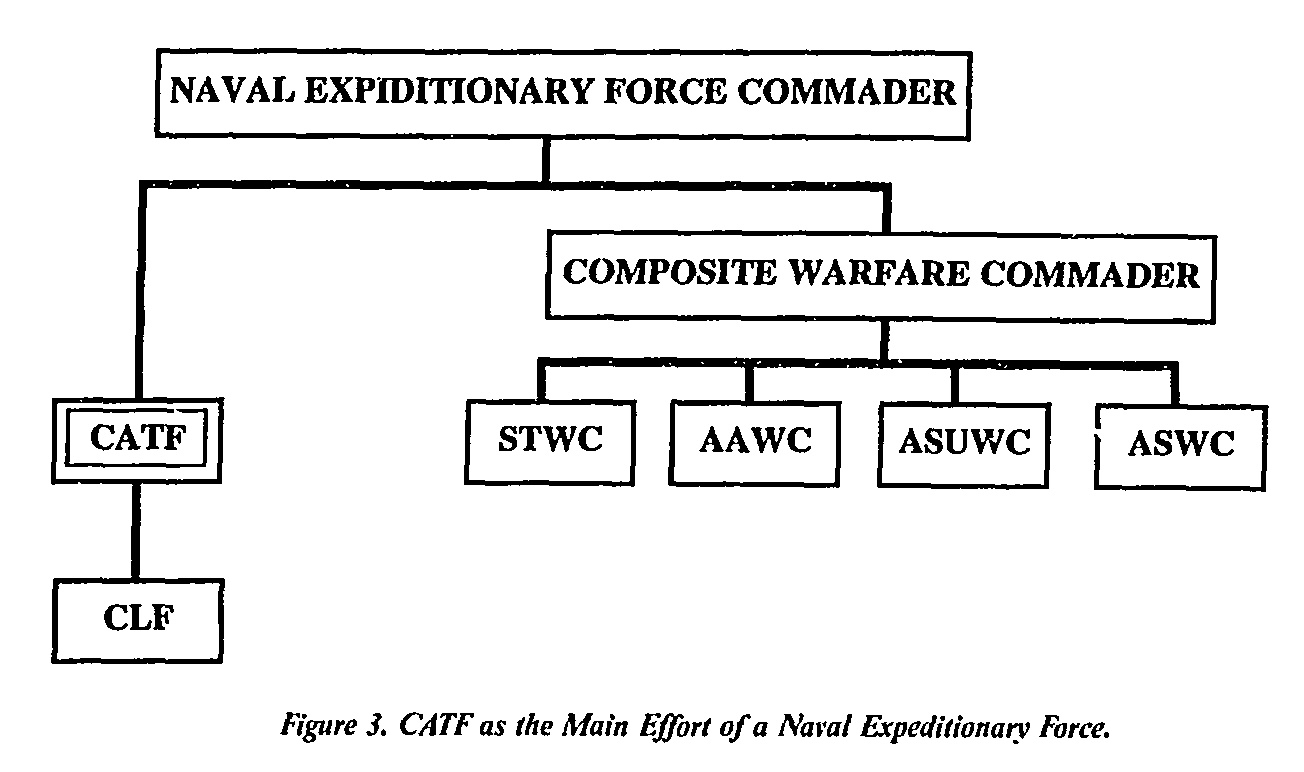

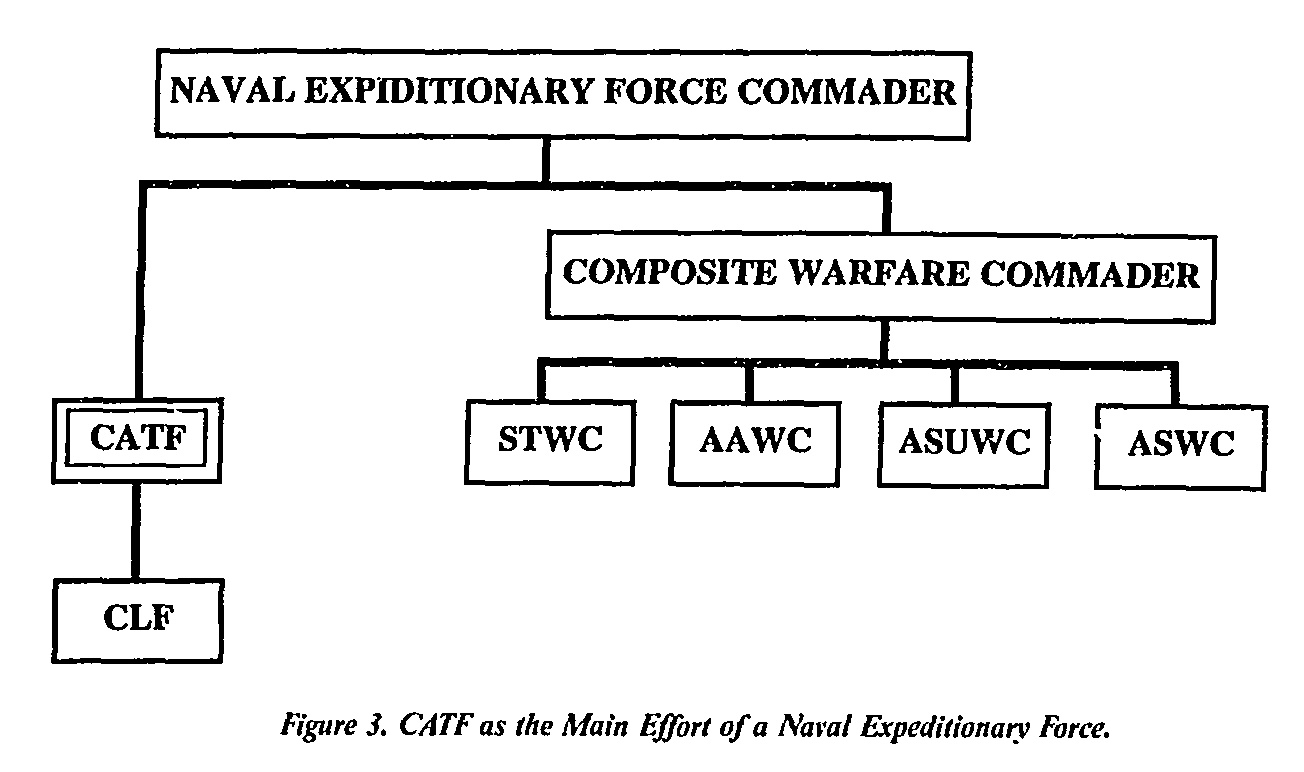

If the NEF commander receives an initiating directive or a warning order for an amphibious operation, he will designate the AWC as the commander amphibious task force (CATF) and the MAGTF commander as the commander landing force (CLF). Likewise, he will designate the CATF as his main effort. Similarly, all other warfare commanders will support the CATF as the main effort until the CATF has completed his mission or the NEF shifts it to another commander (see Figure 3).

If CATF’s primary threat, however, is mine warfare, he may, in turn, designate his mine warfare commander as his main effort. All other warfare commanders will be supporting efforts and do what they can to support the CATF’s main effort. After the CATF achieves mine superiority, he may shift his main effort to the navy commander in charge of the ship-to-shore movement.

For those who are concerned that the entire NEF could be supporting a very junior commander, such as the mine warfare commander, there have been cases where the unit, which is the main effort, is tiny in comparison to the supporting units. Of course, typically in an assault, the main effort is the largest of a commander’s subordinate units. But modern maneuver warfare theory accepts that small units can be the main effort. For example, 5 weeks after the German blitzkrieg began, the main effort of the German attack on the French fortress of La Ferte was a single company of combat engineers commanded by a first lieutenant. Supporting this main effort was the reinforced artillery of an entire army corps commanded by a general.

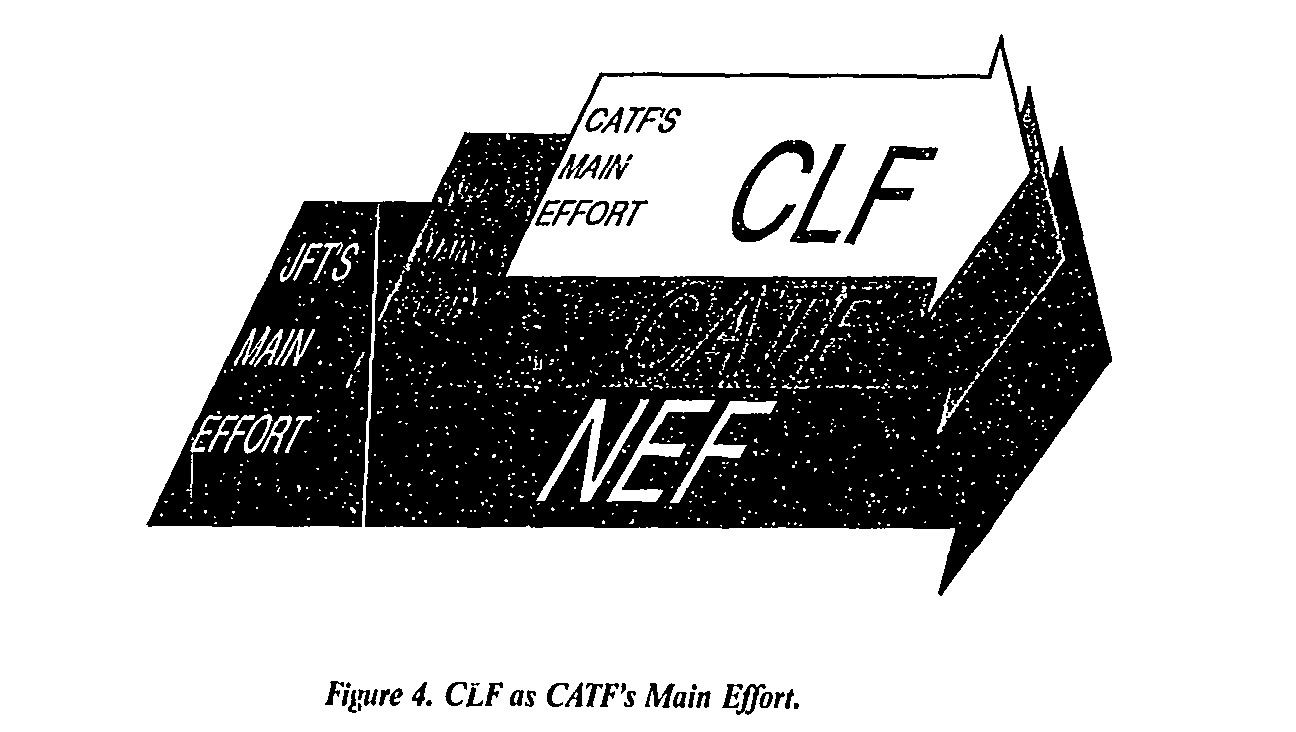

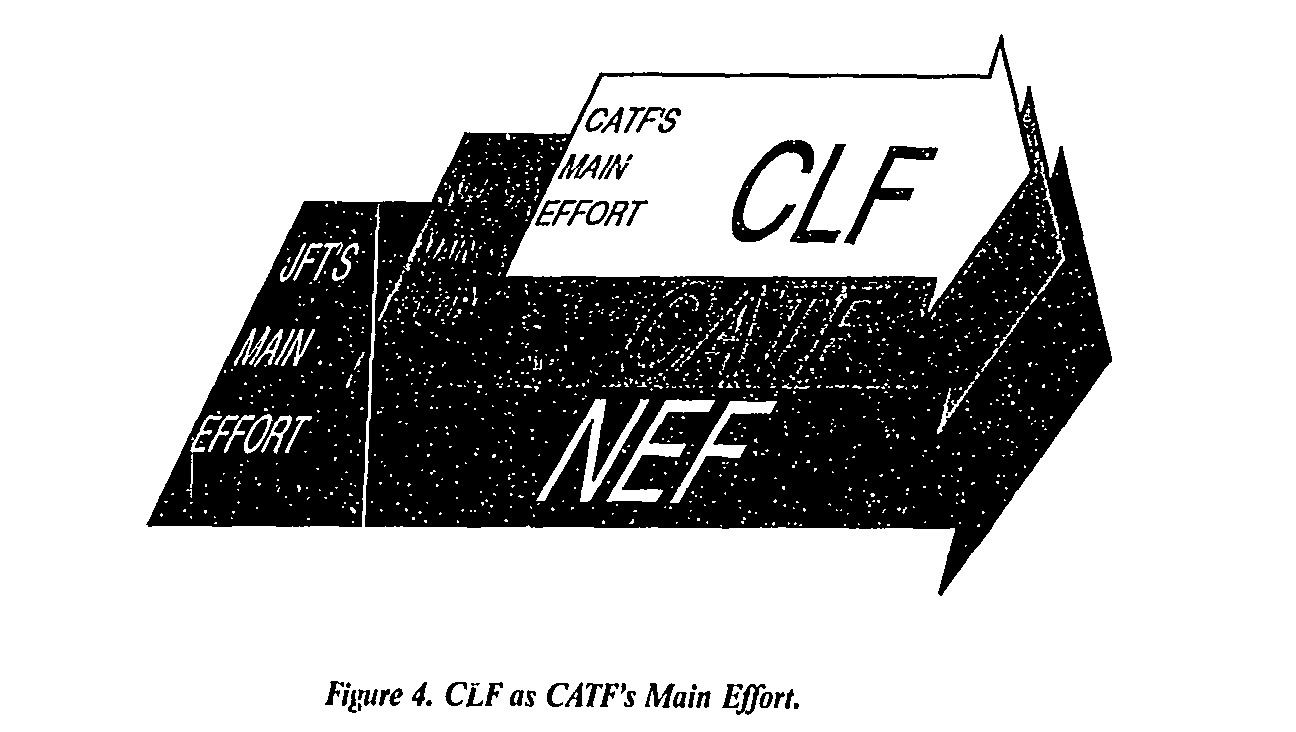

At some point during the amphibious operation, perhaps during the ship-to-shore movement, the CATF will designate his subordinate commander, CLF, as his main effort. Because the operational level of war is central to maneuver warfare, this will be a situational decision based primarily on operational rather than tactical requirements. When this occurs, the NEF commander, the CATF, and all other subordinate commanders will support the CLF in his maneuver ashore. This arrangement, in fact, is very similar to our previous example of the 1940 blitzkrieg into France where Rundstedt, the Group A commander, who is like the NEF commander, designated Kleist’s Panzer Group as his main effort. And Kleist, who is like the CATF, in turn, designated his main effort as Guderian’s Panzer Corp, which functions like the landing force (see Figure 4).

What we have introduced is the concept that within the NEF commander’s main effort, we will have two other main efforts: one is the CATF (as the NEF’s main effort); the other is the CLF (as the CATF’s main effort). While the commander of the NEF always remains in overall command, considerable autonomy and discretion is granted to the CATF, and by extension, to the CLF. Indeed, unity of command is maintained, and we have the flexibility to have all the other warfare commanders support the CLF to accomplish his operational objective.

Continuing our analogy for a supporting effort, we can compare the Navy’s strike force commander to Rommel. Like Rommel, who performed superbly in the role as the main effort of a supporting effort to Guderian, the strike warfare commander (STWC), in turn, can be expected to perform equally as well in the role as the main effort of a supporting effort to the CLF.

For example, because strike air knows the CLF’s intent in maneuvering toward its objective, strike air could continue to take actions to shape the battle to the CLF’s advantage. Examples include using strike air assets to canalize enemy movement in a desired direction or to block or delay enemy reinforcements so that the CLF can fight a piecemeal enemy rather than a concentrated one.

For most amphibious operations, once the CATF designates the CLF as his main effort, the CLF will remain the main effort until completion of the mission. We must understand, however, that during the amphibious phase of the operation the NEF commander can shift the main effort from the CATF to another warfare commander. An example would be, if we were no longer able to dominate the battlespace, the main effort of the NEF could shift to the antiair warfare commander (AAWC) or the STWC until dominance is again achieved.

Even if the main effort shifted from the CATF, the CLF would continue to be the CATF’s main effort. But the CATF would be a supporting effort within the NEF. As such, the CATF and the CLF would no longer be receiving the concentrated support and combat power from the rest of the expeditionary force. After achieving battlespace dominance, the NEF commander could, once again, shift back to the CATF as his main effort.

Solving the CWC and Amphibious Integration Dilemma

Applying this concept of main effort to the NEF should enhance our ability to conduct OMFTS. The NEF commander, quite simply, designates one of his warfare commanders as his main effort for a particular phase of the operation. He may then shift the main effort to another commander in accordance with his plan and developing campaign. This concept solves our problem of how to mesh the CATF and the CLF with the powers of the CWC who is capable of swiftly shifting the forces’ assets to meet rapidly changing threats. In other words, the CWC concept is relevant to littoral warfare if we use the concept of main effort with it.

The immediate difficulty that we in the Navy have with main effort is that it does not appear to be much different from how we now operate. In fact, several of us might argue that when the CWC does not negate a warfare commander’s request to task assets, then he is, at least tacitly, stating his main effort preference. We do not call it main effort, but it is the same thing-isn’t it?

The answer is no. We in the Navy do not understand main effort the same way the Marine Corps does. That is the crux of the problem. When we read about main effort, we look through a blue CWC lens, which only tends to distort the image. As a result, we envision main effort to be a concept where a warfare commander assumes that his assigned warfare mission is the CWC’s main effort. This, however, is not unlike the problem posed when other warfare commanders see their warfare missions as main efforts as well. Of course, the result is that several warfare commanders think and act as if they are the main effort.

We encourage this whenever we ask each warfare commander to task assets as if he were the only warfare commander who could do the job. However, when two warfare commanders simultaneously task the same asset, the CWC commander decides which one has the greater need. Thus, each warfare commander is expected to task, deploy, and fight with all the assets in the force in the best possible manner, to support his mission without regard to how the other warfare commanders might want to task or deploy these assets.

As I have shown, this is not like the concept of main effort. There can only be one main effort at a time, and, if need be, this main effort can shift. In the CWC concept, each warfighting commander thinks of himself as the main effort. This is where the CWC concept falls short in OMFTS. Warfare commanders, like the CATF and CLF, are assigned missions in littoral warfare that require support relationships within the command structure. To make the CWC relevant to littoral warfare, the NEF commander must designate a main effort. He must also clearly identify supporting efforts. And if someone is designated as a supporting effort, he must learn to ask the question, “What can I do to support the main effort?”

In summary, main effort is the tool for providing unity and decisiveness within the NEF. That is to say, main effort is the glue that holds OMFTS together. It allows the NEF commander to focus and rapidly shift his resources to exploit opportunities. When the Navy embraces the concept of “main effort,” the NEF will then exploit its operational mobility at sea and on land. That’s the surest way to guarantee successful OMFTS.