by Maj John F. Schmitt, USMCR

Synchronization-the arranging of battlefield activities in time, space, and purpose to produce maximum relative combat power at the decisive point-has long been a basic tenet of Army doctrine. Since the publication of FMFM 1, Warfighting, Marines have debated the extent to which synchronization concepts apply to maneuver warfare. An article by Maj Kenneth F. McKenzie, published last March, focused the arguments and brought this debate into the open. Brief comments on his article appeared in the June Gazette; here the issue is treated in depth with three articles maintaining that synchronization is incompatible with the Corps’ maneuver warfare concepts and two rebuttal pieces by Maj McKenzie.

Maj Kenneth F. McKenzie’s article “Fighting in the Real World” in the March Gazelle asks whether the concept he calls synchronization supports maneuver warfare or is incompatible with maneuver warfare. In deciding that it does support maneuver warfare and that the Marine Corps should adopt synchronization techniques, McKenzie reaches the wrong conclusion. Not only does synchronization not support Marine Corps maneuver warfare doctrine, it is wholly incompatible with that doctrine.

McKenzie’s description of synchronization is vague and inconsistent. He makes the obligatory references to FMFM 1 as the basis for his beliefs and then promptly contradicts them. Although he insists that synchronization is a collection of practical techniques and procedures rather than a doctrinal concept, he conspicuously avoids discussing any specifics of how these techniques and procedures work or how they fit together to achieve the desired effect. Sometimes his description of synchronization sounds like the definition of combined arms, sometimes it sounds like nothing more than simple coordination, sometimes it sounds like “the plan.” It is not easy to understand exactly what McKenzie is trying to say-this lack of clarity and specifics is part of the reason he can suggest that synchronization is compatible with maneuver warfare.

Some take synchronization to mean nothing more than what is needed to coordinate and prepare our operations-that we cannot just “wing” it. If synchronization is nothing more than coordination and adequate preparation, you will get no argument here. No “maneuverist” will argue that you do not need to coordinate or prepare-although the form the coordination and preparation take may be a matter for discussion. But if that is all synchronization means, there is nothing to be gained by introducing this new term, especially a term that implies much more than that to most people and that, in fact, has a much more specific meaning in the U.S. Army literature where it originated. While McKenzie points out that he has some potential differences with the Army’s implementation of the concept, it is clear he agrees in principle.

In order to discuss synchronization and its implications intelligently, we need to get past the buzz words and ambiguity and come to grips with exactly what the concept really means. Based on the U.S. Army’s and McKenzie’s own descriptions of synchronization, I will develop a model which illustrates the synchronization process in specific theoretical terms. I will then go on to discuss how, based on this model, synchronization is flawed conceptually and how synchronization is incompatible with Marine Corps maneuver warare doctrine as described in the FMFM 1 series.

How Synchronization Works in Theory: A Model

McKenzie writes that “synchronization is an ongoing analytic process that provides a methodology for shaping, not scripting, efforts within the chaotic environment of combat.” In other words, synchronization provides a structured framework for dealing with the disorder of combat. Or put yet another way, synchronization deals with the nature of the battlefield by drawing a box around the disorder, uncertainty, and so on and by providing a structure for dealing with everything inside that box.

In fact, putting things into “boxes” is a natural human approach to creating order and structure in our lives. We store our belongings in boxes. We organize our closets, cupboards, drawers, and bookshelves. We order our files in our filing cabinets. Sometimes we order our understanding of a subject by creating mental compartments (MOOSEMUSS* is an alltoo-common example of trying to compartmentalize our understanding of the art of war). We create boxes on the battlefield by drawing boundaries, phase lines, limits of advance, fire support coordination lines, restricted fire areas, and airspace control areas. In the same way, the synchronization framework, with its intelligence preparation of the battlefield (IPB), battlefield activities, and battlefield geometry, is a box designed to enclose and provide structure to the disorder that is war. The whole key to this approach is whether we can draw our box big enough to encompass all possibilities without having to draw it so big that it becomes useless as a tool for ordering and focusing our efforts. Some things just do not fit well into boxes.

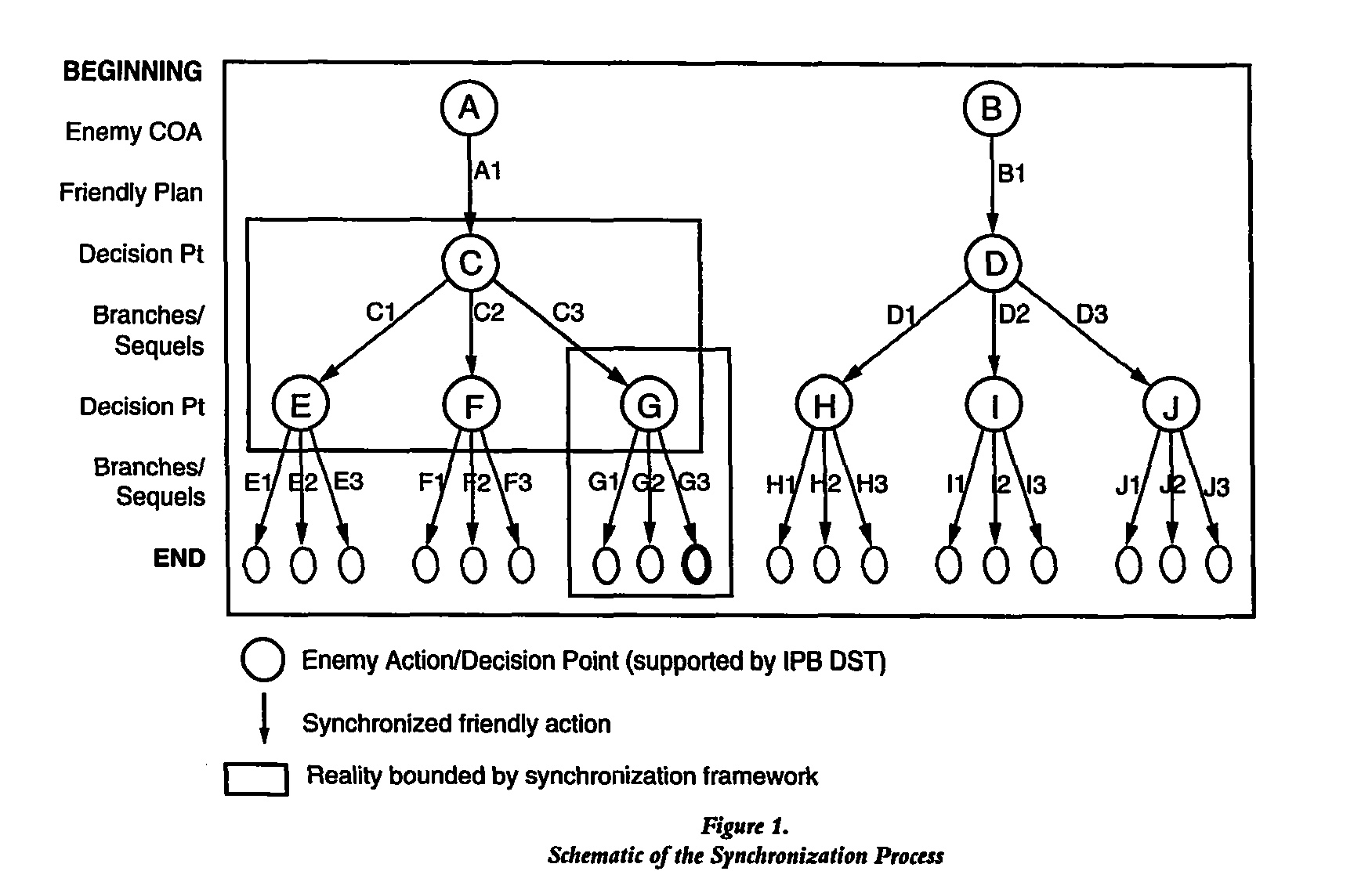

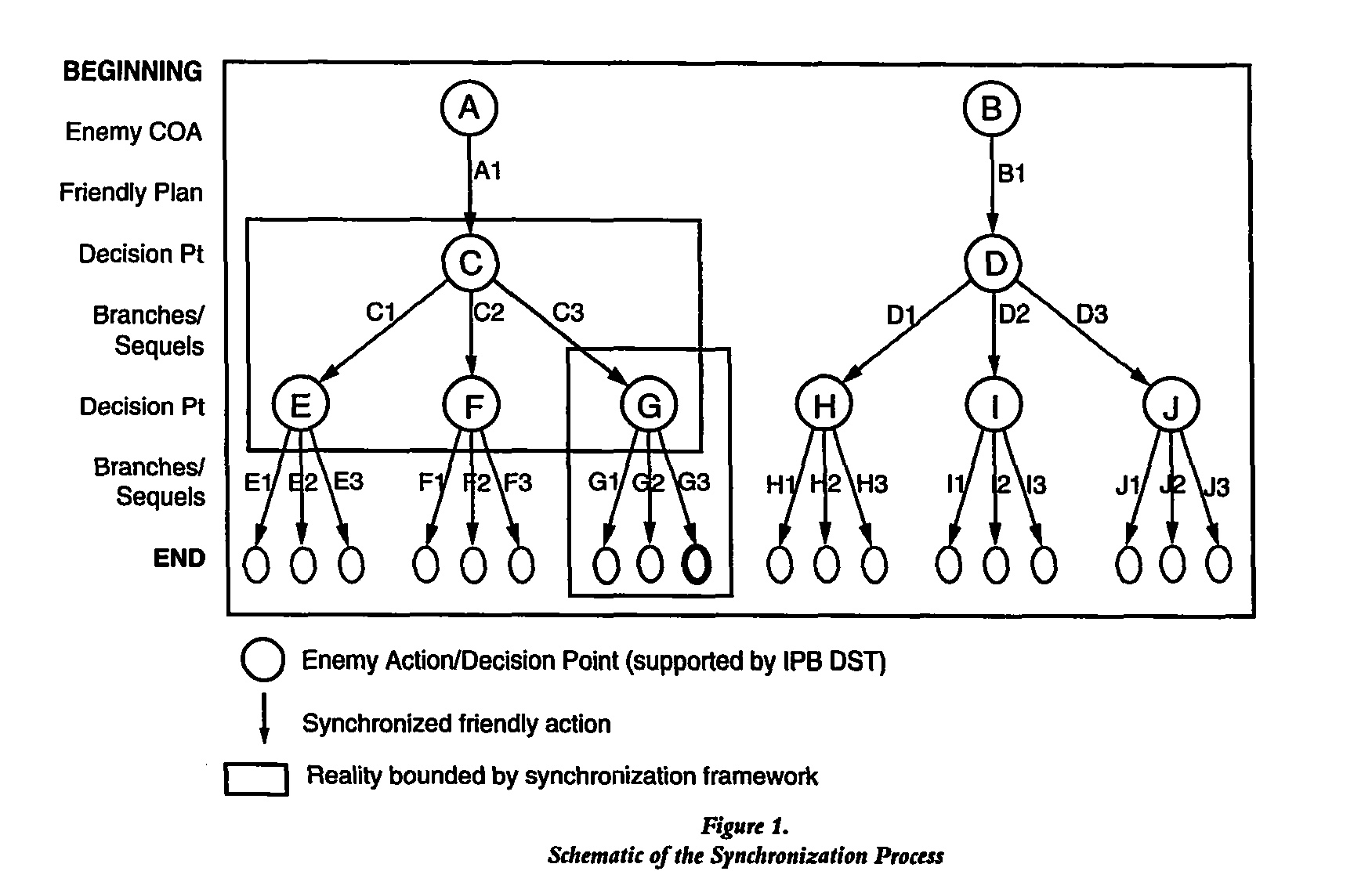

Figure 1 provides a schematic of how the process works in theory. Based on our framework of assumptions about the situation-our “box”-we analyze enemy courses of action, which lead to corresponding friendly plans with associated decision points. Each decision point leads to anticipated branches and sequels, which in turn lead to new decision points and sub

*A mnemonic devise used to help remember the nine principles of war-mass, objective, offensive, security, economy of force, maneuver, unity of sequent branches and sequels. The purpose behind anticipating branches and sequels, in McKenzie’s words, is to “enable the staff and commander to coordinate battlefield activities for future operations.”

In Figure 1, each small circle is driven primarily by the IPB process-the initial enemy courses of action by the initial IPB and the subsequent decision points primarily by the decision support templates (DST) generated as part of ongoing IPB. The arrows, on the other hand, represent the actions that are the results of our and enemy plans and operations. It is within each of these arrows that we would optimize battlefield activities through prior coordination and planning; in other words, this is where the actual synchronization takes place. The gray pathways represent all me possible developments. In McKenzie’s own words, synchronization thus “envisions possible paths to obtain decisive mass and tempo at the proper time and place.” The black cause-and-effect pathway (A-G3), depicting the course of events as it actually unfolds, represents what McKenzie would call the “critical path of concentration and priorities.”

For example, enemy course of action A leads to our adopting predetermined friendly plan A1 that, when combined with the enemy’s actions, logically leads to decision point C. Once the enemy has adopted course of action A (or led us to believe that he has) we stop worrying about path B and focus on what happens after decision point C. We can focus on ensuring the optimal integration of all our assets for the future execution of C1, C2, or C3. Decision point C represents the last place we can choose C1, C2, or C3hopefully, the enemy’s triggering named areas of interest (NAI) during the course of A1 has allowed us to make the determination sooner. Let’s say we choose C3, which leads naturally to decision point G; we can now ignore the E and F paths (and all their subsequent branches) and can focus on synchronizing G1, G2, and G3. And so on. It is not necessary to have laid out the entire structure in advance, but it is necessary to have laid out in advance at least through the next decision point and each of its possible branches. In practice, this requires both the ability to anticipate and the ability to do the necessary analysis, planning, and coordination fast enough to stay ahead of unfolding events. It is precisely this anticipatory ability that allows for the advanced planning and coordination essential to the optimal integration of efforts and resources. This point is absolutely key and bears repeating: The whole object of the synchronization process, in theory, is to allow us to anticipate events so that we can get the jump on the enemy and can develop coordinated, integrated plans in advance.

The foundation of this whole process is, as McKenzie implies, IPB. IPB is the long pole that holds up the synchronization tent; without it, the tent would collapse. It is IPB that establishes the overall framework-draws the “box” of possibilities, in other words-by establishing our set of assumptions. It is the initial IPB that allows us to anticipate enemy courses of action, and therefore to develop our own synchronized plans in advance. It is ongoing IPB, primarily through the use of decision support templates at decision points, that allows us to anticipate events as the operation unfolds and, therefore, again to synchronize our efforts in advance.

As we proceed through the operation (from top to bottom in Figure 1), we can see that the number of options and outcomes increases exponentially. At first glance, this might appear a problem because it is impossible to plan for every potential outcome or variation. But each decision point theoretically provides a narrower framework of possibilities-a smaller “box”-because once we choose a given path, we can shut down the other paths. This continuous narrowing of the framework is absolutely essential to the process; without it we would become overwhelmed trying to deal with all the possibilities.

At the same time, synchronization is theoretically very flexible because, through its cumulative system of branches, it provides eventually for a vast array of possibilities. As we can see from the bottom row of Figure 1 (E1-J3), in theory the anticipated final actions and outcomes pretty much blanket the entire range of possibilities as defined by our framework. There are no gaps in our framework; we’ve covered every contingency. Theoretically, success is merely a function of defining and continuously narrowing the range of possibilities (to allow us to focus our synchronization effort), identifying all the variables (i.e., decision points), and following the proper path to the right outcome.

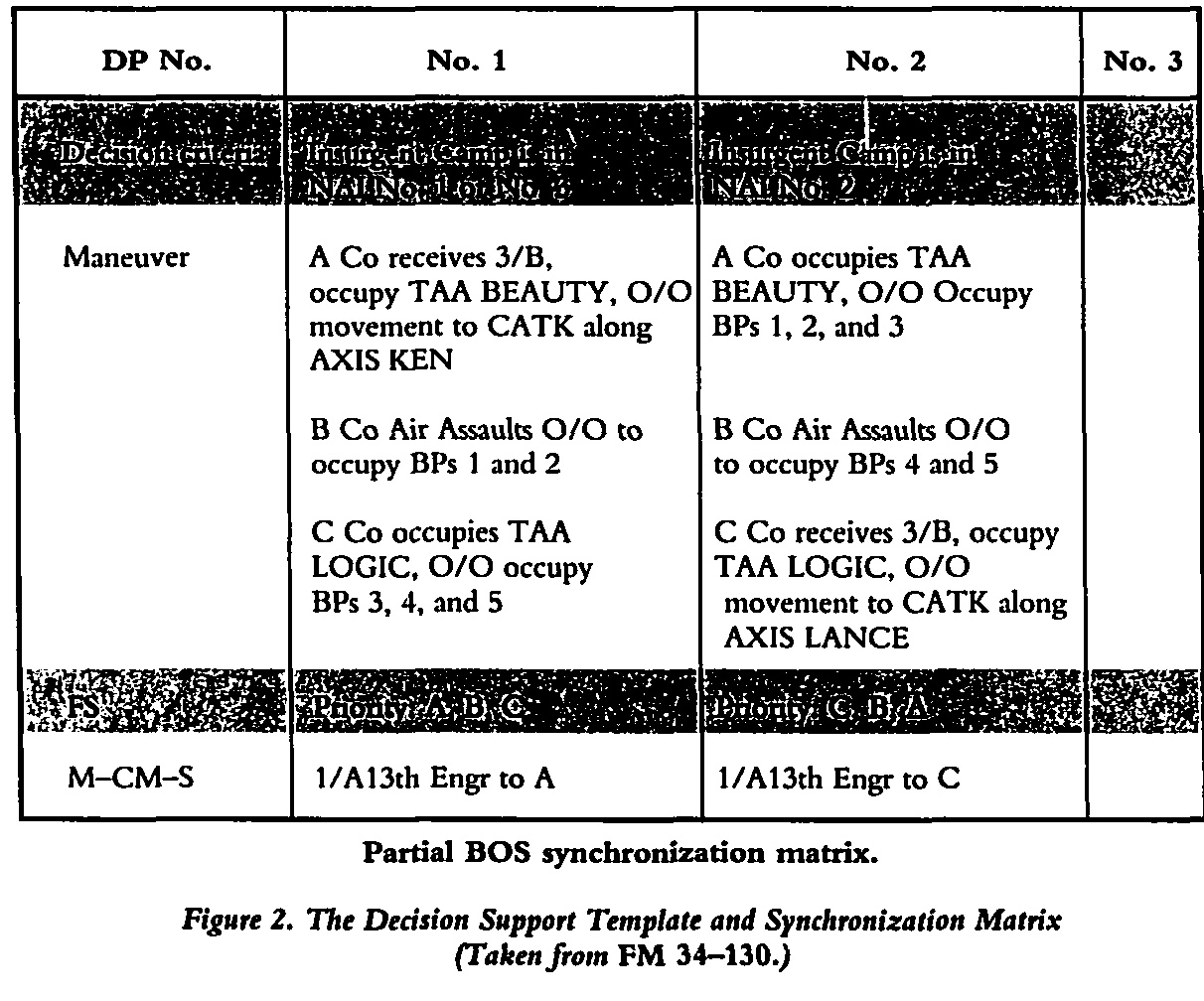

The BOS Synchronization Matrix

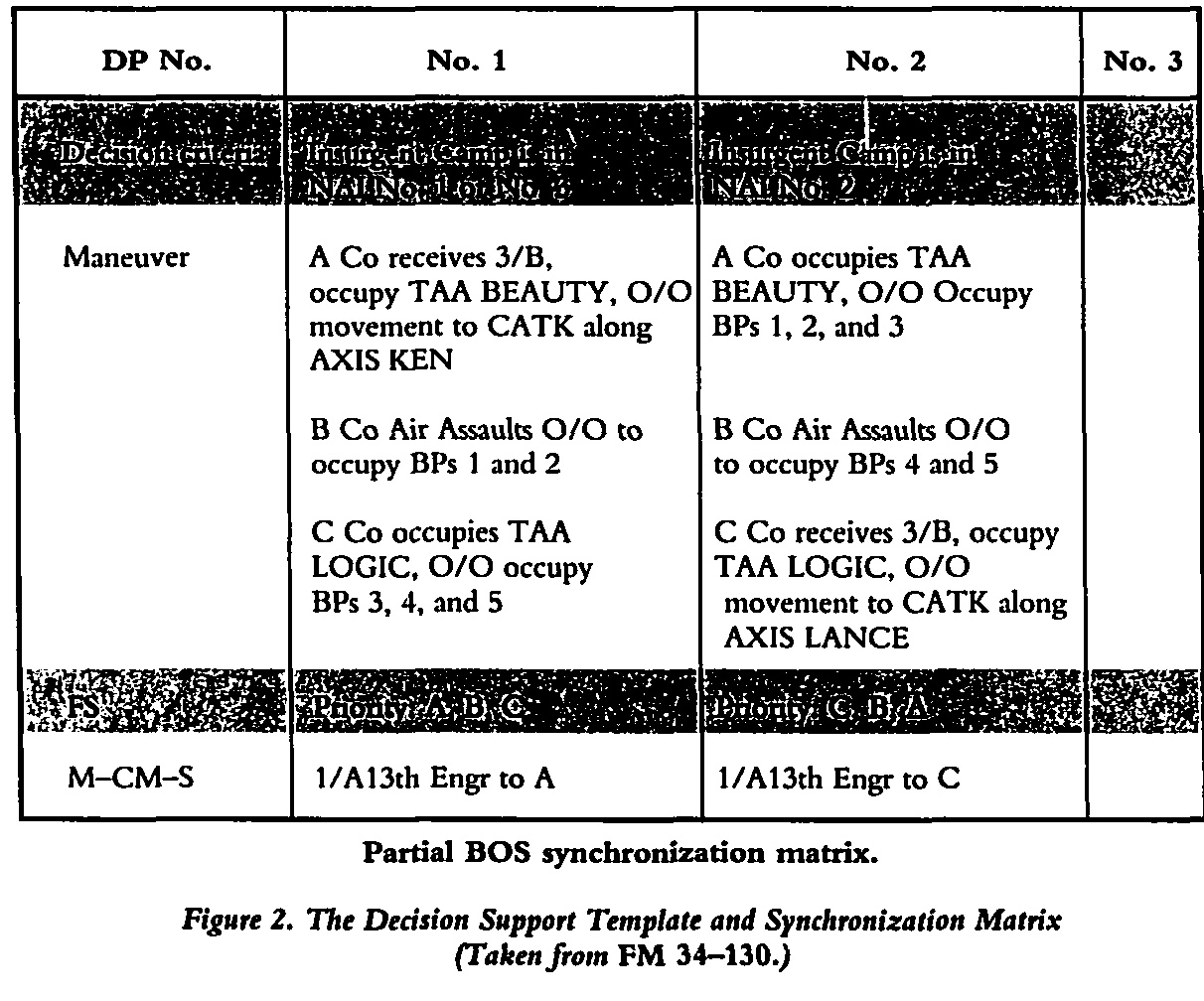

The logical and natural culmination of the synchronization process is the battlefield operating systems (BOS) synchronization matrix. Battlefield operating systems, or what McKenzie calls battlefield activities, refer to the various activitiesmaneuver, fire support, logistics, intelligence, air defense, and so on-which must be integrated optimally in order to achieve synchronization. Each arrow in Figure 1 represents an integrated collection of activities governed by a synchronization matrix. Not only does synchronization enclose combat in a box, it further subdivides that box in order to try to fit combat into a matrix. This matrix is the manifestation of McKenzie’s assertion that “commanders work within the construct of a coherent set of functions intended to optimize the interplay of the various elements of warfighting power.”

In practical terms, the synchronization matrix is a contingency script that lists, on one axis, the various anticipated decision points and, on the other axis, the predetermined actions that each battlefield operating system will take in the event of each decision point being triggered. As the name indicates, the object of the matrix is to ensure the synchronization of all the BOS or battlefield activities. Figure 2 provides a partial sample of a synchronization matrix and a corresponding decision support template.

McKenzie conspicuously stops short of mentioning the synchronization matrix in his article, perhaps because he realizes that it reveals just how mechanistic and quantitative the synchronization approach really is. Supporters of synchronization might argue that we can believe in the process without carrying it to that extreme. But this is irrational. The matrix is the very thing that the whole process is working toward; it is precisely the device that allows us to achieve the optimal “integration of combat, combat support, and combat service support systems in time and space to obtain a sum of combat power that is greater than the simple addition of individual parts”-McKenzie’s words. Why go through the trouble of pursuing optimization only to stop short of the very thing that will theoretically achieve it for you? That makes about as much sense as building a fence around your yard to keep your dog from running away, only to purposely leave the gate open.

What Is the Appeal of Synchronization?

As we can readily see from Figures 1 and 2, synchronization reflects an extremely deterministic and methodical approach to military operations. We can understand the appeal it has for the American mind. It is organized, orderly, and logical. It may be somewhat complicated, but that’s not a problem as long as it is systematic-in fact, to our way of thinking, the more complicated something is, the more advanced it must be. It is also labor intensive, with a heavy reliance on comparative analysis, coordination, and planning. But, again, that is not a problem because we have large, eager staffs ready to do the necessary stubby-pencil work.

FMFM 1 tells us that war is inherently uncertain, unpredictable, frictional, fluid, disorderly, imprecise, and somewhat random. The problem is that these truths do not sit well with Americans in the current culture. We are products of the scientific age that hold that through the scientific method we can master nature. We expect things to go the way we want them to. We crave certainty and precision. We want guarantees. We want to see quantifiable proof. We like to believe that if we take a certain action it will have direct, predictable, and exact results. We like to believe that every question has a right answer, and that if we get enough information and apply the right method we will find that right answer. We strive for optimization and efficiency in all things. We like everything orderly-a place for everything and everything in its place. It is clear that synchronization and IPB are typical products of this mindset.

Unfortunately, the nature of war as described in FMFM 1 is inconsistent with-no, make that contradictory to-this culture. This is why the adoption of maneuver warfare is not merely a matter of doctrinal change but of cultural change. Meanwhile synchronization holds out the alluring but irrational promise that we can have it both ways: Yes, war is inherently uncertain, random, chaotic, and frictional, but we can still get certainty, precision, order, and optimization. Like a security blanket, synchronization provides a false sense of security. Like a belief in magic, it allows us to ignore the laws of nature.

How Does the Synchronization Model Deal With the Unexpected?

Marines are agreed that war is the province of the unexpected. Our doctrine consequently places a premium on initiative. McKenzie writes:

The entropic nature of combat will challenge all plans, but a planning and analysis structure that recognizes the inevitability of change will be able to accommodate these occurrences.

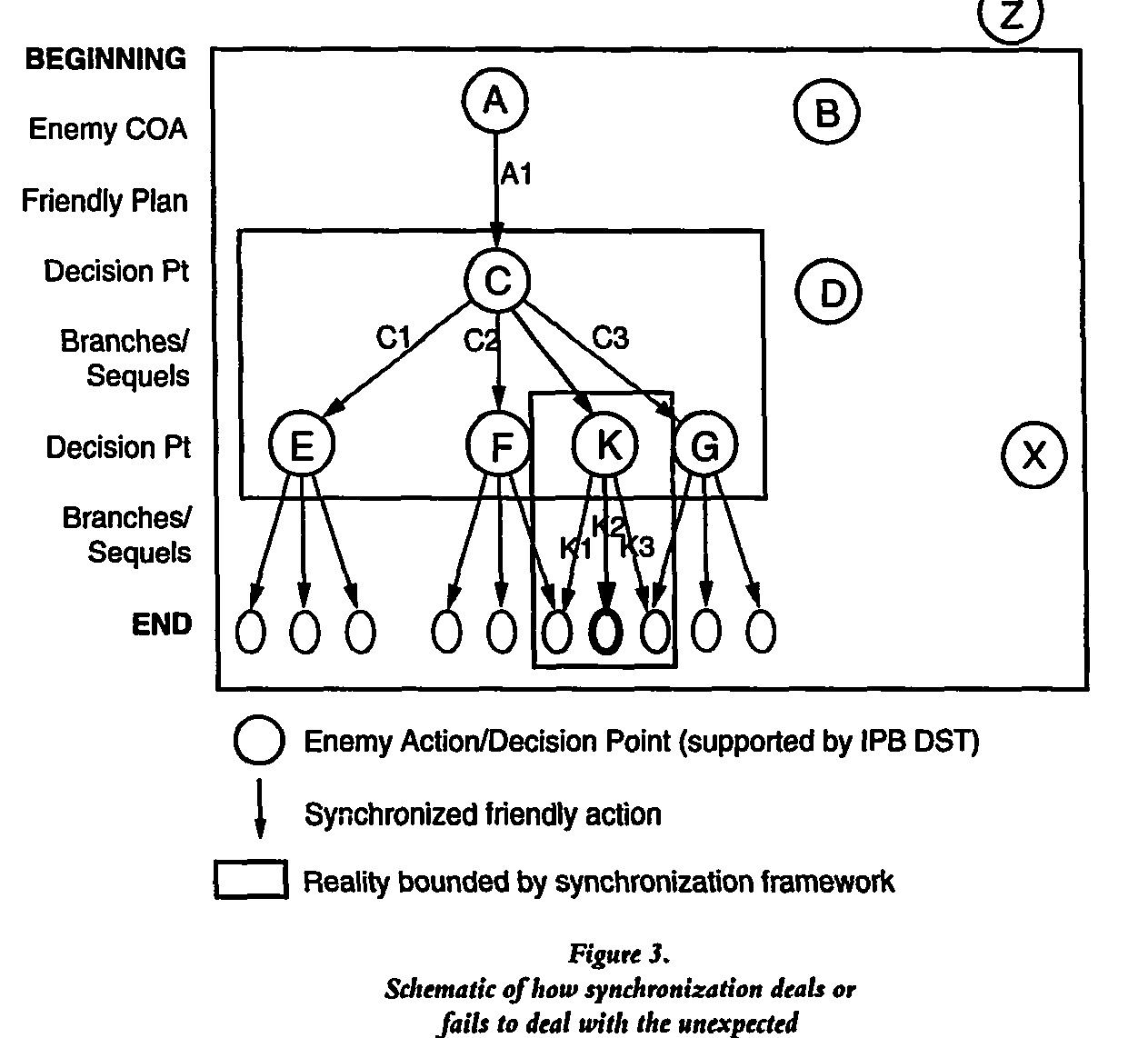

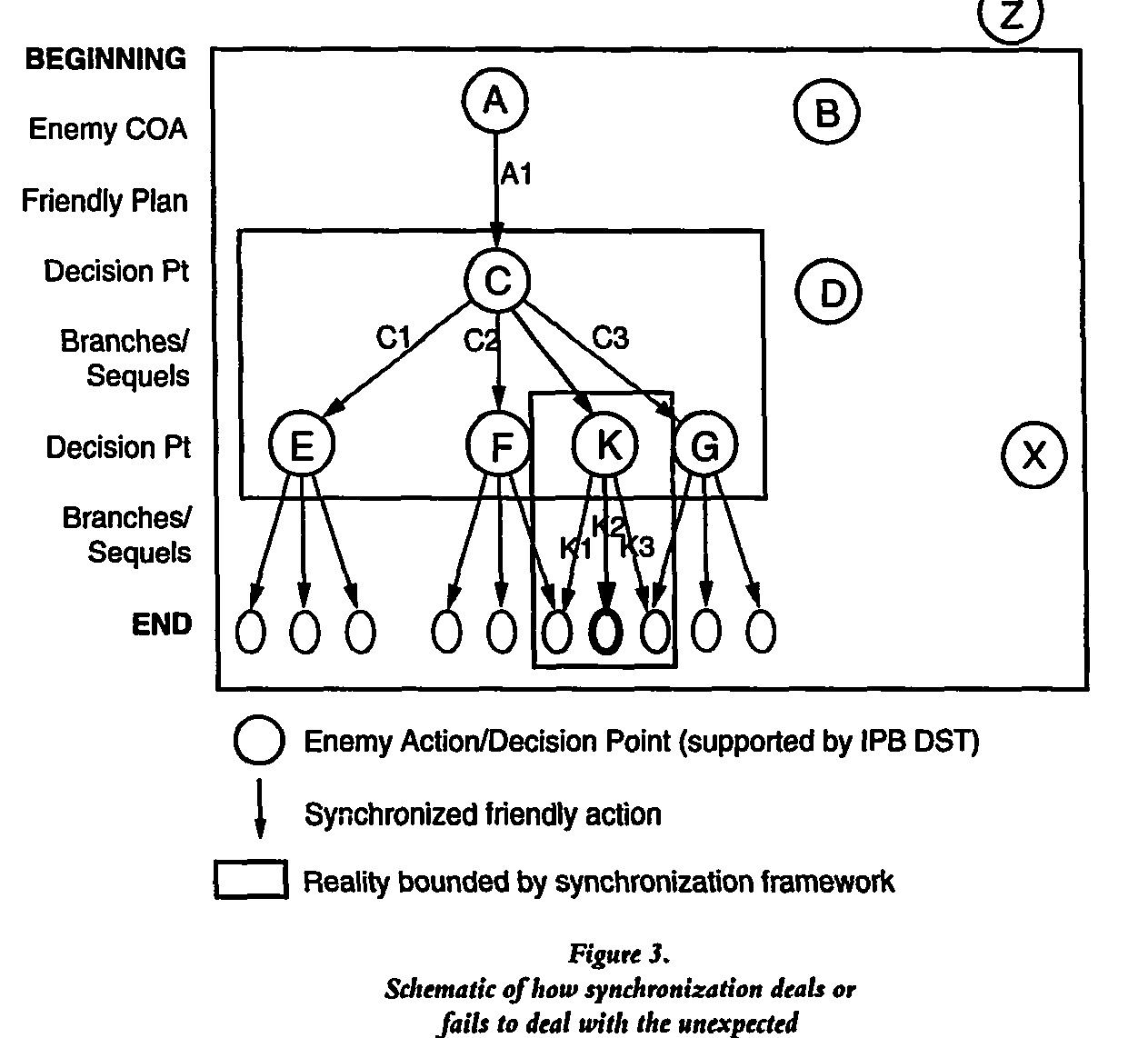

So how does synchronization deal with the unexpected and allow room for initiative? Figure 3 is a schematic showing how this works in theory. Say that the enemy chooses course of action A, which leads to action A1 and eventually to decision point C. Suppose that we reach C, but none of the anticipated branches (C1-C3) are quite appropriate given the situation. Although it is not an event we anticipated exactly, it does not violate any of the basic assumptions that decision point C is based on. It is still within our box. Let’s say it is somewhere between C2 and C3. We can interpolate the requirement and adopt new course C4. Most of the synchronization already done for C2 and C3 can be applied with some modification. C4 leads to new decision point K, and K leads to more branches (K1-K3), all of which are still bounded by our established framework-that is, they are within our basic set of assumptions. In this way we exercised “initiative” at decision point C to improvise branches C4 and, later, K2. Even though a plan was not specifically developed in advance, as long as events are within the bounds of the established framework, synchronization thus theoretically provides the means to adapt. This is how McKenzie can argue that it is possible to exercise initiative within the synchronization framework. We should make it clear, however, that when we use the term “initiative” in this sense, it has a much more limited meaning than is typically used. McKenzie betrays this reality when he makes the admission that “conceptually, synchronization is counter-poised against agility and initiative.”

Problems With the Model

There are some basic problems with the synchronization model. First, what happens when events fall outside the bounds of the framework? In other words, what happens when our basic assumptions are wrong? Figure 3 illustrates this schematically. For example, say that the enemy chooses course of action A, as we anticipated he might, and so we appropriately adopt friendly course A1; but-due to fog, friction, chance, an enemy who doesn’t act logically, whatever-the result does not take us to decision point C as we expect, but instead to X, an event which is not envisioned by the C range of possibility-it’s outside the “box.” X bears little resemblance to C or any of its branches. We have not developed, nor even considered, any branches or sequels developing out of X. As a result, the whole process is stillborn. Or let’s say that we have correctly identified the enemy’s two possible courses of action (A and B), but that the enemy has cleverly deceived us into thinking he is choosing A when he is really choosing B (not so hard to do if we are ready to believe he is choosing A and are merely waiting for him to trigger a NAI as confirmation); instead of ending up at decision point C we end up at D, which is part of the original B pathway. You might say that we simply shift to the D path, adopting D1, D2, or D3. Unfortunately, in order to keep the amount of analysis, planning, and coordination down to a reasonable level, that entire pathway was shut off from above when our IPB led us to decision point A vice decision point B. Again, the whole process is stillborn. Or, perhaps most dangerous of all, what if the enemy doesn’t choose either of our two anticipated possibilities in the first place? Let’s say that instead of A or B, he chooses Z, completely outside our widest framework? For example, we are expecting an armor attack along avenue of approach A or B; not only does he not choose either avenue, but he doesn’t even launch an armor attack-instead he mounts a light-infantry infiltration. Like the North Koreans when MacArthur landed at Inchon, we are taken completely by surprise and are completely unprepared to deal with it. What we have in this case is catastrophic failure of the synchronization process. In any of these examples, none of our existing or envisioned branches and sequels will work, and we do not have a framework for adapting. Remember, the whole process is predicated on the ability to anticipate. Once we have failed to anticipate the next decision point with at least some degree of accuracy, from that point on we cannot synchronize and the process cannot work. And what happens then to a military that has come to depend on synchronization?

The second basic flaw with the synchronization model is the time factor. Marines are agreed that time is a critical factor in combat and that the aim is to generate a higher tempo than the enemy. In fact, that is the whole basis of maneuver warfare. Of course, we have to assume that the enemy also realizes this and is trying to do the same thing to us. But the synchronization model does not account for time. Synchronization is a fundamentally methodical approach requiring explicit analysis, planning, and coordination. While the stated aim of synchronization is to increase tempo by allowing us to anticipate the enemy, in practice the time-consuming techniques and procedures upon which synchronization is based make this impossible. An Army officer at the School for Advanced Military Studies in Ft. Leavenworth confided that in order to have the time to do the things needed to synchronize operations at the division and corps levels, it is necessary to predict the enemy’s actions a full 72 hours in advance. In other words, at that level (which equates roughly to the Marine expeditionary force level), it takes 72 hours to mount a synchronized operation. The model assumes we will have the time to accomplish all the necessary procedures. But what if the enemy simply does not give us the time to execute the method? What if he does not worry about the optimal integration of his assets but would rather just be fast? What if we simply cannot work through the IPB and synchronization techniques in time? If we cannot keep up with developing events, then we cannot possibly anticipate. And, as we have mentioned, once we fail to anticipate, the process is scuppered. This is essentially what happened to the French in 1940; the Germans denied them the time they needed to implement their plans.

The third basic flaw with the model is its failure to account for the human element, which our doctrine tells us is central in war. War is made up of the actions of countless people-friendly, enemy, and neutral-and we cannot rely on them all to act rationally. Yet the synchronization process assumes that operations will unfold in a predictable and logical chain reaction of cause and effect. It is based on recognizable patterns and “If A, then B” sequences. It is important to note that the Army originally created IPB, the foundation of synchronization, specifically in response to the Soviet threat-a supposedly doctrinaire and systematic conventional enemy whose patterned operations were easily transferable to graphic templates. Not surprisingly, the Army is having much less success shoehorning IPB to fit various, less-structured low-intensity operations. What if the enemy is an unorganized rabble with no doctrine or infrastructure to speak of? What if the enemy does not feel at all compelled to adhere to his established doctrine? Or what if the enemy’s doctrine specifically calls for him to act unpredictably and without discernible patterns (as maneuver warfare does but synchronization definitely does not)?

The final basic flaw with the model is, I think, the most significant and by itself invalidates the whole synchronization process. Any model is merely a simplified representation of reality. Reality is rarely as neat and clean as the model representing it. But in order to work, the model must reasonably approximate the reality. If the model has little resemblance to the reality it purports to represent, then it is not of use. It may in fact be worse dian useless-it may actually mislead us into belief and actions that are inconsistent with reality. Consider the following passage from FMFM 1:

In an environment of friction, uncertainty, and fluidity, war gravitates naturally toward disorder. Like the other attributes of the environment of war, disorder is an integral characteristic of wan we can never eliminate it. In the heat of battle, plans will go awry, instructions and information will be unclear and misinterpreted, communications will fail, and mistakes and unforeseen events will be commonplace. It is precisely this natural disorder which creates the conditions ripe for exploitation by an opportunistic will.

Each encounter in war will usually tend to grow increasingly disordered over time. As the situation changes continuously, we are forced to improvise again and again until finally our actions have little, if any, resemblance to the original scheme.

The flaw with the synchronization model is that, even taking into account that the model is a necessarily simplified representation, the process it describes bears little resemblance to the reality described in this passage.

The Inherent Nature of War

McKenzie readily accepts this description of combat. He writes that:

Synchronization in the Marine Corps context encompasses a set of techniques and procedures designed to enhance performance within the chaotic battlefield envisioned by the philosophy of maneuver warfare.

He has got the problem right, but he has got the solution all wrong. By trying to create order on the inherently chaotic battlefield, through its systematic and methodical approach, synchronization will not enhance performance but instead will seriously hamper performance. To be effective, any doctrine, tactic, technique, or procedure must come to grips with the natural environment of combat. There are two basic ways to try to do this. The first is to try to overcome the inherent nature of war, to turn it into something it’s notin other words to impose smoothness, certainty, order, and structure. The other is to recognize war for what it is and to learn to function in that environment Clearly, with its heavy emphasis on optimization, detail, explicit coordination, geometry, templates, matrices, and so on, synchronization derives from the former approach. However, doctrinally, through the FMFM 1 series, the Marine Corps has clearly adopted the opposite approach. This is a fundamental point. Any approach that does not recognize this, such as the effort to incorporate synchronization, is fundamentally incompatible with maneuver warfare doctrine.

The Failure To Understand Maneuver Warfare

This leads us to the next point, namely that the argument for synchronization reflects a failure to understand the concepts that are the very basis of maneuver warfare. McKenzie starts the article out with the following assertion:

Through an evolutionary doctrinal process, the Marine Corps is reestablishing the primacy of the Marine air-ground task force (MAGTF) command element (CE) as the principal warfighting headquarters at all levels of the air-ground team.

McKenzie’s opening statement is just flat wrong and once pointed in the wrong direction, the article never recovers its bearings. A move toward the primacy of the MAGTF command element would be by definition a move toward centralizationthe MAGTF command element becomes increasingly more important in relation to subordinate echelons. McKenzie has a very good reason for wanting to establish this point: Synchronization is impossible without centralization; there is no other way to achieve the high level of analysis or integration required. But, in fact, the evolution of Marine Corps doctrine, as evidenced by the FMFM 1 series, has been clearly in the opposite direction. Our doctrine strongly and clearly advocates decentralization by increasing the authority and responsibility placed on lower echelons. Our doctrine requires that the authority for initiative and decisionmaking be pushed down to the lowest possible level as a means of generating tempo, adjusting to disorderly and rapidly changing situations, and overcoming friction. This is another fundamental point. If you do not recognize it, then your argument from this point on will be inherently flawed.

Theories of Control

There is much more to this than simply the question of centralization versus decentralization. Fundamental to the issue of synchronization is the question of the Marine Corps’ overall philosophy of command and control, since synchronization deals with how we command and control our forces in the conduct of operations. As military historian Martin van Creveld points out in the classic Command in War, the defining feature of the challenge of command and control is the problem of uncertainty. Van Creveld asserts that the entire history of command in war can be described as a “quest for certainty,” a quest that, given the inherent nature of war, he eventually concludes is futile. There are two, and only two, possible responses to the problem of uncertainty. The first is to pursue certainty (or as close to it as possible) as the basis for effective command and control. The second is to accept uncertainty as a given and to learn to cope with it by creating a command and control system that does not require a high level of certainty to function effectively. These two responses lead to two opposing theories of control. Each theory in cum provides the basis for a distinctly different practical approach to command and control.

The first theory, stemming from the pursuit of certainty, is called detailed control. The second, deriving from the acceptance of uncertainty, is called mission control (or directive control). Detailed control tries to eliminate uncertainty by creating a powerful, highly efficient centralized command and control apparatus able to process huge amounts of information and intended to reduce nearly all unknowns. Mission control takes the opposite approach. Rather than increase the degree of certainty that we achieve, we reduce the degree of certainty that we need. Detailed control stems from the belief that war is systematic and deterministic, and that through efficiency and sheer effort we can impose structure and certainty on the inherently disorderly and uncertain battlefield. Mission control stems from the acceptance that war is inherendy chaotic, meaning that the best we can hope for is probabilities rather than certainties. Detailed control is centralized, formal, and inflexible, relying on control measures, detailed planning and analysis, and elaborate and precise procedures and methods. Orders and plans are thorough and explicit and their successful execution requires strict adherence to the plan and minimizes subordinate decisionmaking and initiative. Mission control is decentralized, informal, and flexible. Orders and plans are brief and simple, relying on the judgment of subordinates in execution.

Detailed control seeks to achieve unity of effort by means of tight, centralized control that aims at the precise-dare I say synchronized?-integration of all subordinate elements. Naturally, there is little tolerance for any deviation from the plan, much less for the exercise of outright initiative by subordinates. In mission control, by contrast, unity of effort is not the product of conformity imposed from above, but of the spontaneous cooperation of all the elements of the force. Subordinates are guided not by detailed instructions, control measures, timetables, or event matrices, but by their knowledge of the requirements of the overall mission.

In detailed control, discipline is imposed from above. In mission control, that imposed discipline is replaced by selfdiscipline throughout the force. Relying on detailed planning and analysis, detailed control seeks to “optimize”-that is, to reach the optimum plan of action. Detailed control aims at precision. Where detailed control seeks to optimize, mission control recognizes that there is no perfect solution to any battlefield problem and instead seeks to “satisfice”-to pick the first course of action which will work. Mission control willingly sacrifices precision for speed in the belief that precision is a futile goal given the inherently disorderly nature of war. Mission control aims instead at the “eighty percent” solutions. Detailed control is essentially a top-down approach to command and control, emphasizing vertical, linear communications-linear meaning that reports and requests go up and orders come down. Mission control is essentially a bottom-up approach, relying on horizontal as well as vertical, and interactive vice linear communications.

Where Does Synchronization Fit?

Clearly, the concept of synchronization is quite compatible with the characteristics of detailed control. The emphasis on optimization, analysis, detailed anticipatory planning, and adherence to the plan fit right in with a top-down, centralized approach to control. In fact, it is quite easy to see that IPB, with its deterministic, mechanistic, and systematic emphasis on generating operational templates and anticipating enemy courses of action, is the brainchild of this mindset.

Just as clearly, however, we can see that, from a rational point of view, synchronization is entirely, irreconcilably incompatible with mission control.

What’s the Significance of This?

Understanding the difference between these philosophies of command and control is fundamental to understanding maneuver warfare as practiced by the Marine Corps. Fortunately, as Maj Eric Walters points out in his adjoining article, we have two excellent historical examples of hightempo, maneuver-oriented militaries adopting vastly different command and control styles based on the opposing philosophies: The Germans, who adopted a mission approach called Auftragstaklik, and the Soviets, who adopted a system based on extreme detailed control. Clearly, the U.S. Army, so concerned with fighting the Soviets for half a century, has bought into the Soviet model. This is abundantly clear if you read the Army’s version FMFM 1, FM 10O-5, Operations. On the other hand, the FMFM 1 series makes it just as clear that the Marine Corps has taken the opposite approach and adopted mission control as the basis for its command and control philosophy. Make no mistake about it, the Army and Marine Corps philosophies as described in their respective keystone doctrinal manuals are fundamentally different. Regardless of what you think of synchronization as a concept, there is no denying that it is rationally consistent with the official Army philosophy. It is just as rationally incompatible with the Marine Corps’ stated philosophy. You cannot take a concept that is the product of one specific paradigm and apply it blindly to another, opposing paradigm; it won’t fit.

The ironic thing, as Walters points out, is that while the synchronization enthusiasts in the Army and elsewhere move ever closer to the Soviet model, the Soviets themselves abandoned it in the late 1980s, after over four decades of trying, they decided it just doesn’t work. Of course, due to peculiar political and cultural factors that existed in the Soviet Union, the Soviets had a much more compelling reason than we have for giving detailed control a try in the first place.

Your View of the Nature of War

It all comes down to your fundamental view of the inherent nature of war. Do you believe that war is admittedly complicated, confusing, disorderly, but yet somehow ultimately deterministic and systematic? Do you believe that results are predictable and logical? Do you believe that the chaos and uncertainty of the battlefield can be mastered and provided with a governable structure and order? Do you believe that we can anticipate the enemy’s actions with enough accuracy often enough to make that the basis for the way we operate? Do you believe that we can fit the conduct of war neatly into a box? If so, then synchronization makes rational sense.

Or do you believe, as FMFM 1 asserts, that war is fundamentally, intractably chaotic and probabilistic? Do you believe, as FMFM 1 states, that war is the province of human vagary and therefore inherently unpredictable? Do you believe, as FMFM 1 argues, that the unexpected and unanticipated will be commonplace? Do you believe, in fact, as FMFM 1 urges, that it is the unforeseen event that provides the greatest opportunity for exploitation and the unexpected act that has the greatest chance of decisive effect? And do you believe, as FMFM 1 insists, that speed is essential in war and that we should do whatever we can to increase our own speed relative to the enemy, even at the expense of order and optimization? Do you believe, in short, that the conduct of war will not fit neady into that box? If so, you realize that synchronization is incompatible with Marine Corps maneuver warfare doctrine.

I mentioned earlier that the key question was whether it was possible to draw the synchronization framework big enough to encompass the nature of combat without having to draw it so big that it loses all usefulness as a structuring tool. To read our own doctrine, the answer is, clearly, No. You can support the Marine Corps view of maneuver warfare. You can support synchronization. You cannot do both.

At one point, McKenzie states: “The greatest threat to synchronization is a commander who is unable to accept uncertainty as his handmaiden in battle.” Once again, he’s got it backwards. The greatest threat to synchronization is actually the commander who will accept uncertainty as his handmaiden; for such a commander, recognizing that synchronization is incompatible with his view of reality, will readily and quickly dismiss it. For our own good, let us hope there are plenty of such Marines out there.