The threshold of the new millennium reveals a world poised for instability. Comprehensive studies suggest that the 21st century environment will be one of crisis and conflict. Nation-states, and an ever-expanding lineup of nonstate actors, will continue the age old struggle for mastery, wealth, and security in a world increasingly provoked by exploding populations, depleted resources, cultural strife, and ideological differences. Most daunting will be the challenges these conditions create in the expanding sprawl of urban littorals. The resulting conflicts will vary in complexity and lethality, from humanitarian assistance operations to full-scale conventional warfare-possibly conducted simultaneously within a shared battlespace. 7hese challenges will shape future military requirements.

A traditional strength of U.S. military forces has been their ability to meld distinctive capabilities, competencies, and cultures into flexible, multimission capable forces. But this strength also presents a challenge: to fight effectively as a joint force, while retaining individual component strength with specialized roles and missions. In a period of fiscal constraint, Services must choose capabilities carefully while filling gaps and minimizing duplication. Responding to multidimensional threats requires the ability to seamlessly and rapidly integrate widely dissimilar-and possibly dispersed-combat forces.

AN OMFTS FORCE: ANSWERING NEW CHALLENGES

The white papers, . . . From the Sea and Fortvard. . . From the Sea, sought to fulfill our Nation’s strategic requirement for maritime forward presence and initial crisis response by initiating a new approach to naval operations that places increased emphasis on the littorals. The Marine Corps expanded upon this warfighting philosophy with Operational Maneuver From the Sea (OFITS), our capstone operational concept that describes the marriage of maneuver warfare and naval amphibious operations. Embarked aboard Navy amphibious ships, carrier battle groups, and maritime prepositioning ships the Marine air-ground task force (MAGTF) will employ OMFTS principles as a self-contained combined arms force to accomplish strategic, operational, and tactical objectives. Task organized and integrated at all levels, it provides a unique forcible entry capability-through focused combat power with minimal logistical footprint-to serve as an exploitation force, a decisive force, or as an enabler for follow-on forces. The OMFTS MAGTF will conduct missions across the spectrum of conflict, providing mission depth without losing momentum or effect. This enduring commitment to naval expeditionary operations as a core competency will proactively steer the Marine Corps into the next century, and will continue its primacy as the Nation’s forward deployed airground force in readiness.

THE ‘A’ IN MAGTF

The aviation combat element (ACE) as an element of maneuver has evolved from a supporting arm of the ground combat element (GCE) to an integral combat arm of the MAGTF. Like all other elements of the MAGTF, the ACE is a unique, critical, combined arms component of an integrated force. It provides the MAGTF commander a task-organized force possessing operational relevance and tactical focus. Able to rapidly deploy and immediately employ, the ACE delivers its operational capability through speed, mobility, and flexibility. Marine aviation‘s culturebased, “true expeditionary” nature resides in its ethos and is emphatically ingrained in its doctrine, training, and the shared vision common to all Marines. The ability to operate from large and small naval platforms, austere positions ashore, and established airfields equates to ACE responsiveness and allows the MAGTF to focus and magnify combat power. The ACE remains objective oriented, supporting the MAGTF scheme of maneuver across the spectrum of conflict; however, the concept of OMFTS marks a significant change in the way the MAGTF will conduct maneuver warfare.

MAGTF ACE: A CATALYST FOR OMF-S

Just as OMFTS is shifting the focus of the MAGTF, so shall it demand a significant shift in emphasis and magnitude of traditional ACE activities. Aviation operations will transcend traditional linear, sequential applications of power. The MAGTF commander will utilize inherent ACE capabilities-mobility, speed, depth of influence, lethality, responsiveness, and battlespace perspective-as the catalyst to negotiate the obstacles that time and space present. In close coordination with the other elements of the MAGTF, the ACE will enable rapid power projection, create the conditions necessary for decisive action and sustain the force to a degree greater than heretofore envisioned.

From Technologies to Tactics: OMFTS necessitates a greater degree of interdependence and cohesion between the elements of the MAGTF than ever before. That is why it makes little sense to have one element of the MAGTF frame its contributions along functional lines that are unique to itself-as in the case of the six functions of Marine aviation. In the future all the elements of the MAGTF will frame their contributions as they relate to battlefield functions: command and coordination, power projection, and sustainment. It is important to note that Marine aviation will continue to perform the six functions that it has in the past-but these functions will now be framed and discussed in terms that are common to all elements of the MAGTF.

COMMAND AND COORDINATION OF ACE OPERATIONS

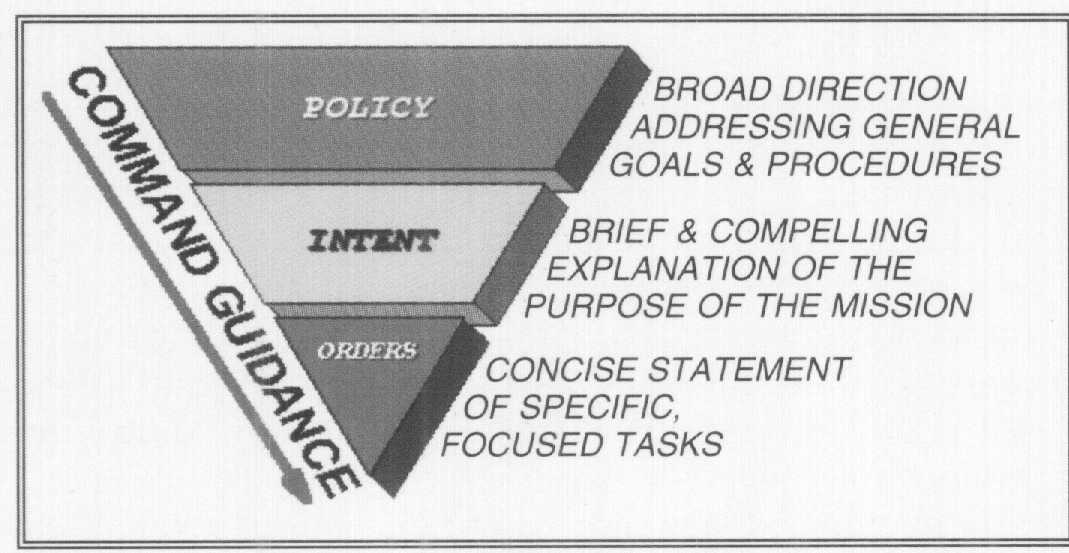

During OMFTS operations command and coordination begins with the MAGTF commander. The ACE commander exercises command over aviation forces through commander’s intent and mission-type orders. He provides guidance which is ultimately translated into actions and processes that organize, plan, coordinate, and direct all ACE operations toward accomplishing the MAGTF mission. Therefore, the primary aim of ACE command and coordination-the process through which “control” is embedded within the exercise of ACE command-is to provide the ACE commander with realtime access to relevant information while reducing uncertainty to acceptable levels. ACE command and coordination empowers the ACE commander to act decisively in support of MAGTF operations.

COMMAND INFORMATION ARCHITECTURE

The future MAGTF command information architecture will provide both internal and external MAGTF connectivity. It will provide a single database, a common operational picture, and the tools needed to rapidly collect, process, analyze, and exchange information in support of ACE operations. ACE platforms and information systems will play a significant role as a conduit for MAGTF connectivity by allowing information to rapidly “flow to/through” without human intervention. Key elements of the architecture include:

Interoperability: Compatible and interoperable with naval and joint command information systems, enhancing lateral and vertical coordination in both voice and digital data formats.

Accessibility: Easily accessible, affording the ACE commander with a flexible means to “plug into” the architecture and influence ACE operations from virtually any location in the battlespace.

Reachback: Enables the ACE to quickly and efficiently access and exploit available information, intelligence, operations, and support assets-through the vast resources of our national power-regardless of the physical location of the assets or individuals involved.

INTELLIGENCE

The ACE will not only use intelligence, but will be a primary contributor to the intelligence process. Both manned and unmanned ACE assets will routinely conduct deliberate data collection against stated MAGTF requirements through aggressive, proactive reconnaissance, surveillance, acquisition, and assessment activities. Collected information will be fed into a shared database, providing invaluable intelligence “pieces” to the overall common operational picture. Processing and dissemination of intelligence must be accomplished through the MAGTF command information architecture to support OMFTS. Intelligence must be protected, but to be truly effective in combat it must also be available, relevant, and free of “black box” restrictions.

FACILITATING ACE COMMAND AND COORDINATION

The future dictates a single MAGTF command information architecture. However, this will not negate the need for an “aviation module” within that architecture that can translate the ACE commander’s intent into aviation specific capabilities, or to effectively and efficiently transform airframes into focused air power. This requirement stems from the myriad aviation unique tasks that ACE command and coordination must perform, from precision controlled approach to detailed airspace deconfliction. ACE command and coordination will not be simply an “equipment set,” instead we will use specially trained Marines that focus functional aviation capabilities. Today’s Marine air command and control system will provide the foundation from which ACE command and coordination will emerge.

Enabling ACE Command Functions: The essence of command will not change, and will be exercised through ACE command and coordination. Empowered with a broad perspective of the battlespace and enhanced situational awareness (SA), the ACE commander will graphically track the prosecution of the Aviation Plan in realtime-intervening only when the situation requires, or when actions diverge from his intent. Finally, ACE command and coordination must provide the ACE with the capacity to coordinate with other Service and allied nation aviation agencies.

Maximizing Efficient Planning/Air Direction Functions: The ACE commander will implement the MAGTF commander’s apportionment guidance, allocate and task assets, and issue orders through ACE command and coordination. Planning functions must become more responsive, increasing overall efficiency within the air tasking cycle. Interactive, computeraided collaborative planning, connectivity and reachback capabilities will enable effective planning for tomorrow’s events while providing the full asset visibility and SA required to permit dynamic in-flight retasking. This true mission-in-progress replanning capability is essential in the rapidly changing maneuver warfare environment envisioned by OMITS.

Streamlining Air Control Functions: Air control functions will be accomplished through the MAGTF common operational picture; however, increased air control decentralization and flexibility are required to respond to changing situations and unanticipated opportunities. Seamless connectivity must replace positive point-to-point air control. We must exploit intuitive information filtering systems, pattern recognition tools, advanced information technologies, integrated sensor grids/arrays, and sensor-to-shooter connectivity to maximize situational awareness. The management and dissemination of the information most relevant to each user will be key. ACE systems will be modular, using common, integrated data formats.

APPLYING ACE COMMAND AND COORDINATION TO OMFTS

ACE command and coordination must respond to Marine aviation‘s expanding roles within OMITS. It must possess the capacity to affect flexible command relationships, and emulate the mobility and responsiveness of other MAGTF elements.

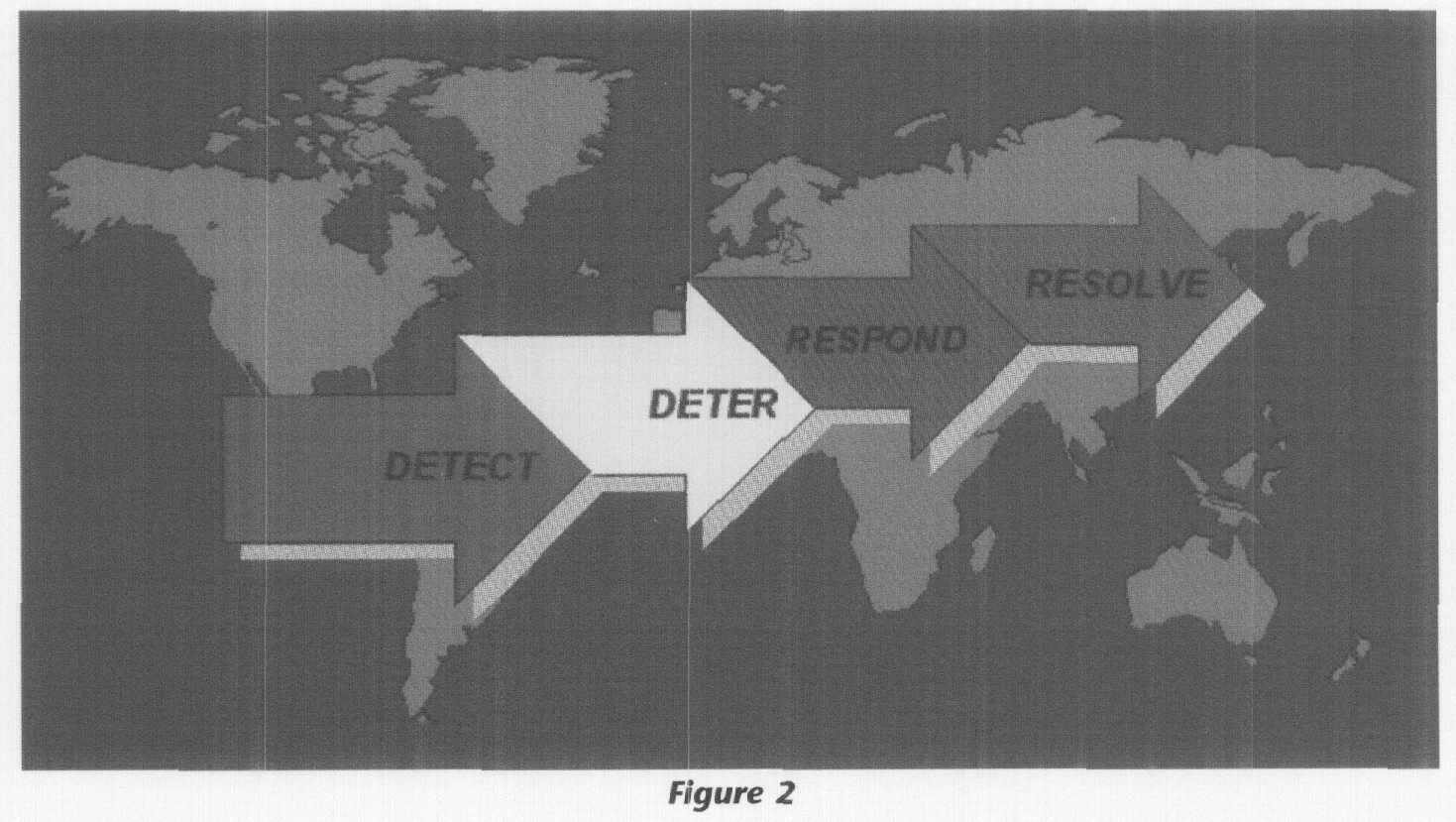

Aviation Relationships: Forward deployed MAGTFs, as a part of a naval expeditionary force, are often the first to respond to a crisis. ACE command and coordination must enable stand-alone aviation operations, yet also provide a foundation to integrate follow-on forces and assets into a working joint task force (JTF) command structure-to include nontraditional elements of national power. When the MA_GTF serves in this JTFenabler capacity, the ACE commander may be tasked to serve as an enabling joint force air component commander (JFACC). This will require ACE command and coordination to exercise JFACC command functions-and in some cases exercise operational control-over other Service and allied nation aviation elements.

Seabased ACE Command and Coordination: ACE command and coordination will remain seabased to the greatest extent possible to limit infrastructure ashore, permit the mobility and agility required for high tempo OMFTS operations, and to reduce exposure to hostile actions. To accomplish this, shipboard spaces must be designed and allocated to support ACE command and coordination requirements. Some tactical situations may require the ACE commander to move a portion of his functions ashore. The extent of such displacements will depend upon the mission, the location of the preponderance of ACE assets, and the requirements of the MAGTF commander.

THE ACE ROLE IN MAGTF POWER PROJECTION

The MAGTF projects power by applying maritime maneuver and combined arms resources to achieve a desired operational result or decisive influence ashore. OMFTS will place unprecedented reliance upon ACE capabilities, increasing its relevance across the full breadth of power projection activities from battlespace shaping through reconstitution. ACE contributions to the warfighting functions of maneuver, fires, and force protection will enhance our ability to achieve decisive action, and amplify the MAGTF‘s power projection capabilities overall.

ACE MANEUVER

OMFTS seeks to extend the boundaries of maneuver warfare by viewing both land and sea as maneuver space. The ACE adds the vertical dimension to maneuver, but more importantly it supports the MAGTF commander’s scheme of maneuver bv dramatically expanding his reach throughout the battlespace. Thus, the MAGTF gains a decisive, natural advantage over its adversaries within the context of time and space. In the conduct of OMFTS, the MAGTF will initiate power projection from beyond the visible horizon, with its elements executing rapid, simultaneous maneuver in concert with commander’s intent. The ACE must support this aim bv continuing to improve upon its inherent ability to exploit time and distance factors, and by reducing the current limitations they impose. The ACE’s mobility, range, speed, and battlespace perspective are well suited to the elements of maneuver warfare: tempo, enemy focus, surprise, combined arms, and flexibility. ACE maneuver, characterized by decentralized control, applies to all facets of MAGTF power projection. ACE contributions such as physically maneuvering MAGTF assault forces and enabling maneuver through suppression and local airspace domination are familiar to the MAGTF; however, OMFTS will require ACE warfighting advancements to include the enhancement of maneuver through logistics movement, and employment of the ACE as an element of maneuver. Future ACE operations must fully capture and support commander’s intent, which may include opportunities for the ACE to serve as the primary maneuver element-or main effort-in an operation. This will require a recalibration of old mindsets that simply depict the ACE as long-range artillery.

During seabased operations, efficient deckspace management will be critical to maneuver and operational tempo. The sea base must afford all-weather launch and recovery of a flexible, vertical/short takeoff and landing (V/STOL) ACE, and expeditiously accommodate massing or dispersing forces. The MAGTF cannot allow deck area to constrain force size, and the ACE can never relinquish the capability to operate in close proximity to the GCE. To achieve desired sortie generation rates and rapid aircraft turnaround, precise amounts of fuel, ammunition, logistics, and ACE-specific services must be available at shore locations. Thus, the ACE must possess an organic capability to establish and operate flexible expeditionary sites ashore, ensuring responsiveness and endurance. The ACE will not “phase ashore” in the traditional sense, but operate within a continuum comprised of both seabased and shore positions.

ACE FIRES

The MAGTF utilizes fires to achieve a desired operational effect by destroying or disrupting adversary capabilities through which he derives freedom of action, physical strength, or will to fight. The MAGTF will call for and direct organic fires, and will have access to available nonorganic naval and joint fire support-to include spacebased systems. Aviation fires must be available in all weather conditionsboth day or night-and be precise, lethal, efficient, versatile, sustainable, and coordinated.

The command information architecture will connect the cockpit with supported elements through onboard systems that download realtime mission information such as fuel state, ordnance availability, weapon effects footprints, and intelligence/mission feedback. Fire support coordination agencies can utilize this shared data to develop appropriate weapons-to-target pairings and achieve effective resource utilization. Combat identification (CID) measures embedded within the architecture, in tandem with onboard target detection/acquisition/identification systems, will be applied to each potential target to ultimately prevent incidents of fratricide. Collectively, these capabilities will ensure a timely target validation/confirmation process which can support extensive requests, taskings and retaskings of ACE fires in close proximity to ground forces. This process will satisfy reasonable assurance thresholds and SA requirements for all participants, permitting ACE weapons platforms to engage targets without “eyes on” verification.

Nonlinear approaches to fire support coordination measures will provide ACE assets with flexible access throughout the asymmetric battlespace. Roving restricted fire areas will provide increased opportunities to make best use of available ordnance. The overall objective is to achieve the most efficient and effective use of ACE assets by minimizing squandered weapons, lost sorties, and requirements for repeated attacks.

Engaging targets in an urban environment will pose complex challenges. Adversaries will use the proximity of noncombatants to their advantage, requiring us to rely more heavily on precision weapons and systems that are capable of a greater degree of target discrimination. The ACE requires an enhanced family of munitions-both lethal and non-lethal-which can achieve a broad range of desired effects and also provide due regard for friendly locations, proportionality, collateral damage, and “rubble” factors.

FORCE PROTECTION

The asymmetric battlespace presents significant force protection challenges. The broad spectrum of missions and distance factors are compounded by the number of disparate agencies that will require protection. Layered protective measures must be designed to cover not only military forces, but for all involved joint/combined agencies and local citizens within our area of influence. The ability to extend protection over vulnerable business entities, critical information networks and resources, nongovernmental organizations, and noncombatants must become part of our overall force protection effort. The goal is to effectively protect our forces without diminishing our offensive capabilities.

Force protection is not an end unto itself, but a byproduct derived from the synergistic integration of all warfighting activities. The OMFTS MAGTF capitalizes on seabasing, force mobility, stealth, and speed to achieve maximum force protection effect and ensure continued freedom of action from predeployment through reconstitution and redeployment. The ACE will seek to exploit these principles for its own benefit, but will also closely integrate with the sea base to provide the far-reaching umbrella of security essential to effective force protection. ACE activities will focus on detecting, identifying, and defeating enemy offensive actions. The ACE will provide local air superiority, tactical recovery of aircraft and personnel, localized ground security, and airspace control functions-further contributing to force protection. The command information architecture must support these ACE capabilities, and provide means to coordinate them across joint/combined boundaries-both afloat and ashore. When ACE elements operate ashore, locations will be carefully selected to maximize capability and versatility, and to mitigate vulnerability. ACE assets ashore charged with defending MAGTF assets must be at least as mobile and survivable as the elements they are supporting.

ACE SUSTAINMENT OPERATIONS

Sustainment activities will physically integrate, prepare, deploy, supply, train, maintain, reconstitute, and redeploy the force, constituting the measures necessary to support the MAGTF throughout OMFTS. The maritime prepositioning force (MPF) pillars provide a force sustainment framework. Yet in addition to MPF, the MAGTF will take advantage of all available elements of national power, to include leveraging successful business practices to streamline its resource management-acquisition/distribution and repair-and ensure right time/right place support.

RESOURCE ACQUISITION/ DISTRIBUTION

Efficient, dependable resource acquisition and distribution is critical to maintaining operational tempo. Resources will be acquired from sources internal or external to the ACE, in some cases requiring the means to engage in contractual arrangements. Reachback capabilities will ensure accessibility to distant resources and may even employ commercial carriers to expedite deliveries. ACE supply systems will connect with joint, automated systems that can identify, request, acquire, track, receive, and distribute resources through total asset visibility. Once located, the ACE will assign assets to move and distribute resources in support of itself and of the MAGTF as a whole. Deliveries will be tailored into specific support packages that maximize “in-time” delivery and economy of lift.

RESOURCE REPAIR/ MAINTENANCE

ACE maintenance provides for actions necessary to classify discrepancies, perform necessary repair or modifications, and dispose of unusable material. Future ACE assets will take advantage of technology to simplify troubleshooting procedures without reducing thoroughness. Systems will self-diagnose discrepancies, transmit the repair requirement into a networked computer system that, in turn, will automatically schedule phase and routine maintenance, identify repair and/or support system components, and order the appropriate resources. Exploiting such technology will require increased skill sets in maintainers; yet, common operating systems/environments for all aircraft, ground equipment, maintenance systems, components, and repair processes will ultimately lessen the load placed upon them. Maintainers will have required resources and support systems in place when the asset is available for maintenance, decreasing turnaround/down time and improving readiness. Contractor support and modular ACE systems will reduce the intermediate level structure, moving toward “skip-echelon” maintenance procedures that float components directly from operational to depot levels.

LOGISTICAL FOCUS

The ACE requires the ability to effectively operate while being logistically supported from a sea base, yet it must also retain the ability to provide flexible, adaptable, and maneuverable support from shore locations. Regardless, OMFTS shifts much of the MAGTF sustainment burden to the ACE, requiring it to provide operational sustainment and tactical logistics support both for itself and the MAGTF. To accomplish this, the ACE will shift its mindset and “operationalize” sustainment activities, executing them from within the context of a “complete tactical focus.” Marine air must simultaneously carryout both tactical and logistics functions-providing the lifeblood for the MAGTF at the operational level, while managing muscle movements at the tactical level. To carry this increased portion of MAGTF sustainment, the ACE requires the proper number of assets, intelligent resource management, and the connectivity to coordinate disparate efforts into a cohesive, holistic package.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Maneuver warfare places a heavy reliance on initiative. We must train our tactical operators at the most junior level-flight and section leads-to proactively exploit commander’s intent and maintain an operational tempo that is overwhelming to the enemy. Our command architecture must recognize the inherent presence of friction in battle, and support training opportunities in peacetime that capitalize on building leadership, judgment, and initiative.

Marine aviation stands at a crossroads. The Joint Strike Fighter USF) and MV-22 represent the fruition of a forward thinking neck-down strategy that began nearly 2 decades ago. Not simply airframes, aviation as a whole has participated in this philosophy promoting efficiency, commonality, and expeditionary capability. To perform OMFTS the ACE must continue this trend toward efficiency in operations, commonality in support, lethality, and flexibility in execution. The following represent some key future ACE characteristics.

ASSETS & AIRCRAFT

Multirole, multisensor, modularly upgradeable, all weather, reliable airframes.

V/STOL, able to operate from ‘L’ class ships without performance degradation.

Commonality with joint platforms in repair and weapons systems and GCE sustainment assets to the maximum extent possible.

Survivable across threat spectrumMANPADS to NBC-employing stealth, active/passive self-protection, advanced tactics.

Configured primarily for attack/lift.

EXPEDITIONARY OPERATIONS

“Lighter” shore operations requires a flexible-in size and services providedexpeditionary shorebased capability.

An ACE organic capability to establish, operate, and protect MAGTF support sites, that provide a conduit for sustainment.

All-weather aircraft recovery capability. Common asset servicing and creative logistics packaging and delivery.

RESERVE INTEGRATION: COMBAT REACHBACK

ACE Reserve organizations to deploy through same modes as active component.

Common equipment and training to improve integration and compatibility.

UNMANNED AERIAL VEHICLES (UAVs)

Provide payload capabilities to support tactical resupply and strike.

Long-range target acquisition, designation, reconnaissance and surveillance (to include electronic) deception decoys, communication/data relay, and electronic jamming.

UAV integration within the command information architecture to gather and disseminate vital information.

MUNITIONS

Family of smaller, enhanced munitions.

Conventional “dial-a-yield” capabilities for urban versus open, and hard versus soft targets.

Cost effective and competent, as well as smart weapons, for level-of-effort fire support.

GCE munitions, ACE transportable in sufficient quantities.

Fire and forget, precision-guided, allweather ordnance. Bring-back capability.

Antiradiation missiles with greater target specificity and “smart” guidance.

ELECTRONIC WARFARE

Proliferation of sophisticated surface-to-air missile systems, integrated through a variety of command and control systems will remain prevalent.

AGE requires layered capability set that includes manned and unmanned assets dedicated to dominating the electromagnetic spectrum, compatible with MAGTF and joint assets.

Ability to rapidly detect, identify, locate, and defeat prohibitive pop-up mobile air defense systems.

Dedicated electronic attack, electronic surveillance, electronic protection assets/measures in conjunction with selfprotection jamming suites and expendables.

Threat warning and ambiguity resolution in signal saturated battlespace, integrated with CID measures, that provide positive identification of all assets and signals.

Operational and tactical capability to deliberately influence (deny, degrade, deceive) an adversary’s information systems and protect our own.

CONCLUSION

In its most complete definition, OMFTS represents a Navy-Marine Corps capability. Naval heritage makes OMFTS a conceptual possibility, but making it a reality necessitates U.S. Navy continued commitment and cooperation. While the MAGTF projects power ashore, the naval expeditionary force operates, maneuvers, and protects the sea base, as well as providing critical fires in support of Marines.

OMFTS represents a cultural paradigm shift calling for ever greater interdependence and closer integration between MAGTF elements. Ground and aviation Marines must immerse themselves in each other’s tactics, capabilities, and limitations to foster our “shared vision” and develop “trust tactics.” This mindset provides an avenue to shed parochial blinders, empowering necessary realignments during our evolution to a new level of expeditionary readiness.

Executing OMFTS does not depend on a revolution in technology, but an evolution in ideology. Taken together, the platforms of the 21st century do not represent sweeping warfare changes and cannot guarantee success in tomorrow’s environment. The revolution resides in the ability to integrate, coordinate, and execute operations-unlimited by physical boundaries and linear thought. OMFTS epitomizes that revolution. MAGTF success depends upon growing and nurturing the leaders who will think, plan, provide their intent, and allow execution in the expanded dimension OMFTS will present. Commanders at all levels must promote inventiveness and initiative in subordinate leaders, creating an environment where fear of failure is not a substitute for success in maneuver warfare.

From its inception, Marine aviation has been an integral and indispensable element of Marine Corps combat power. This position was solidified with the development of the MAGTF, and will be further enhanced in future operations. OMFTS will require the ACE to broaden its scope, cor relating traditional functional areas within the full array of MAGTF warfighting functions and seeking new ways to apply its capabilities. Marine air must operate whenever and wherever Marines operate, overcoming not only aviation specific obstacles, but also those that challenge the MAGTF‘s ability to operate as a coherent whole-across the “three block war” scenario. A MAGTF without organic fixed-wing, multirole, and vertical-lift assault support capabilities is not only untenable, but also unthinkable. Only the synergy of the ACE, GCE, and combat service support element-under the direction of the MAGTF commander-will provide the power and flexibility required of future operations from the sea.