EMW is the Marine Corps’ capstone concept for the early 21st century. It is built on our core competencies and prepares the Marine Corps, as a “total force,” to meet the challenges and opportunities of a rapidly changing world. Capitalizing on our maneuver warfare philosophy and expeditionary heritage, the concept contains the enduring characteristics and evolving capabilities, upon which the Marine Corps will rely, to promote peace and stability and mitigate or resolve crises as part of a joint force. EMW focuses Marine Corps competencies, evolving capabilities, and innovative concepts to ensure that we provide the JFC with forces optimized for forward presence, engagement, crisis response, antiterrorism, and warfighting.

The purpose of this document is to articulate to future JFCs and contemporary joint concept developers the Marine Corps’ contribution to future joint operations. EMW serves as the basis for influencing the Joint Concept Development and Experimentation Process and the Marine Corps Expeditionary Force Development System. It further refines the broad axis of advance identified in Marine Corps Strategy 21 for future capability enhancements. Joint and Multinational Enabling Marine forces possess the capabili

ties to provide the means or opportunity to make joint and multinational operations possible. Enabling operations may be as basic as establishing the initial command and control (C2) system that the assembling joint or multinational force “plugs into,” or a complex as physically seizing forward operating bases for follow-on force Other examples of enabling opera tions include defeating enemy antia( cess capabilities and serving as an operational maneuver element to exploit joint force success or open new fronts. Marine forces are ready to serve as the lead elements of a joint force, act as joint enablers, and/or serve as joint task force JTF) or functional component commanders (i.e., joint force land component commander, joint force air component commander, joint force maritime component commander).

Strategic Agility

Marine forces will rapidly transition from precrisis state to full operational capability in a distant theater. This requires uniformly ready forces, sustainable and easily task organized for multiple missions or functions. They must be agile, lethal, swift to deploy, and always prepared to move to the scene of an emergency or conflict. Operational Reach

Marine forces will project and sustain relevant and effective power across the depth of the battlespace. Tactical Flexibility

Marine forces will conduct multiple, concurrent, dissimilar missions, rapidly transitioning from one task to the next, providing multidimensional capabilities (air, land, and sea) to the joint team. For example, tactical flexibility allows the same forward deployed Marine force to evacuate noncombatants from troubled areas, conduct antiterrorism/force protection operations, and seize critical infrastructure to enable follow-on forces.

Support and Sustainment

Marine forces will provide focused logistics to enable power projection independent of host-nation support against distant objectives across the breadth and depth of a theater of operations.

These capabilities enhance the joint force’s ability to reassure and encourage our friends and allies while we deter, mitigate, or resolve crises through speed, stealth, and precision. Strategic Landscape

U.S. interests will continue to be challenged by an array of national and nonstate actors posing conventional and asymmetrical threats. These threats are made more complex and lethal by the increased availability of militarily applicable commercial technologies. As the technological gap between the United States and its potential adversaries narrows, our leadership, doctrine, and training will be fundamental to maintaining our continued military advantage. We expect potential adversaries to adapt their tactics, weaponry, and antiaccess strategies to confront us on terms of relative advantage. Specifically, adversaries will seek to engage us where they perceive us to be weak. Aware of our ability to degrade complex systems, the thinking adversary will opt for the use of sophisticated but autonomous weapons. Knowing our thirst for information, they will promote uncertainty, confusion, and chaos. This is the venue where our most persistent and determined adversaries will choose to operate. Our Nation must be prepared to fight– worldwide-against adversaries who will seek to engage us with asymmetric capabilities rooted deep in the human dimension of conflict. The Marine Corps, with our philosophy of maneuver warfare and heritage of expeditionary operations, is ideally suited to succeed in this challenging landscape. Expeditionary Advantage

The Marine Corps’ expeditionary advantage is derived from combining our maneuver warfare philosophy; expeditionary culture; and the manner in which we organize, deploy, and employ our forces. EMW capitalizes on this combination, providing the JFC with a total force-in– readiness that is prepared to operate with other Ser-Oces and multinational forces in the full range of military operations from peacetime engagement to major theater war.

Maneuver Warfare

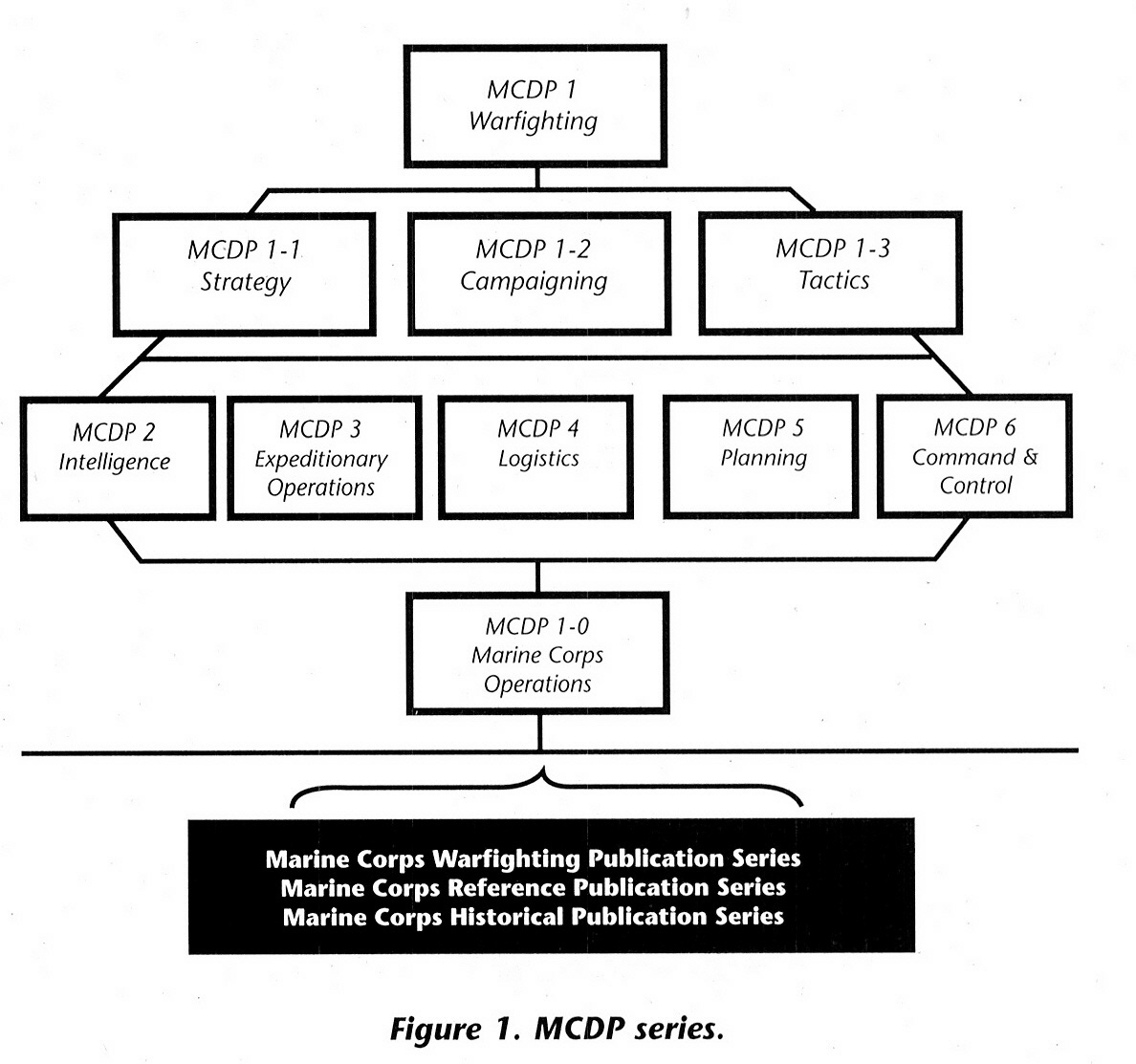

The Marine Corps approach to warfare, as codified in Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1, Warfighting, is the product of years of conceptual development, innovation, and experience. Maneuver warfare, the philosophical basis for EMW, acknowledges the timeless realities of human conflict and does not attempt to redefine war on more humane or less risky terms. The fundamental nature of war-a violent struggle between hostile, independent, irreconcilable wills characterized by chaos, friction, and uncertainty-will remain unchanged as it transcends advancements in technology.

What has changed is the gradual shift in reliance from the quantitative characteristics of warfare-mass and volume-to a realization that qualitative factors (speed, stealth, precision, and sustainability) have become increasingly important facets of modern warfare. Maneuver warfare stresses proactive thought and action, elevating the operational art beyond the crude simplicity of attrition.

It combines high-tempo operations with a bias for action to achieve advantage-physical, temporal, or conditional-relative to an adversary. The aim is to shatter an adversary’s cohesion, succeed in other operations by rapid action to mitigate damage, or resolve a crisis on favorable terms. Maneuver warfare encourages decentralized decisionmaking, enabling Marines to exploit the chaotic nature of combat. Decentralizing decisionmaking allows Marines to compress the decision cycle, seize fleeting opportunity, and engage enemy forces from positions of advantage, which empowers us to outthink, outmaneuver, and outfight our adversary.

Expeditionary Operations

For Marines the term expeditionary connotes more than the mere capability to deploy overseas when needed. Expeditionary is our ethos-a pervasive mindset that influx ences all aspects of organizing, training, and equipping by acknowledging the necessity to adapt to the conditions mandated by the battlespace. Expeditionary operations are typically conducted in austere environments from sea, land, or forward bases. They will likely require Marines and other naval forces to be brought to bear without reliance on host-nation or outside support. As a tangible representation of our national interest, forward deployed and forward based Marines remain both a key element of America’s expeditionary advantage and are critical to the regional combatant commander’s or commander in chief’s (CinC’s) overall strategy.

The regional CinC will set the broad conditions for shaping the battlespace through engagement, forward presence, and the application of a full range of response options. As a critical component of each regional CinC’s Theater Engagement Plan, forward deployed Marine air-ground task forces (MAGTFs) and forward based Marines execute multinational training exercises, conduct mobile training teams, and participate in military-to-military exchanges. Through these activities, Marines develop invaluable regional expertise, cultural and situational awareness, and an appreciation of the interoperability required for successful joint and multinational operations.

Marine forces, as a part of the regional CinC’s engagement strategy, will focus on access operations or other assigned missions as a part of the right mix of joint/multinational forces. These operations may be as basic as establishing the initial C^sup 2^ system that the assembling joint or multinational force “plugs into” or as complex as physically seizing forward operating bases for follow-on forces. Throughout the conduct of operations, Marines will seek to leverage the unique and complementary capabilities of other Services and agencies in order to provide the JFC with a fully integrated force.

Seabasing

Marine forces, as an integral component of a larger naval force, will be prepared to influence events within the world’s littorals using the sea as maneuver space and as a secure “base” from which JFCs can project power to impact the early stages of a potential crisis. Seabasing supports versatile and flexible power projection. Seabasing enables forces to move directly from ship to objectives deep inland and represents a significant advance from traditional, phased amphibious operations. Seabased operations maximize naval power projection and enhance the deployment and employment of naval expeditionary forces by JFCs. More than a family of platforms afloat, seabasing will network platforms and promote interoperability among the amphibious task force, carrier battle group, maritime preposition force, combat logistics force, and emerging highspeed sealift and lighterage technologies. Seabased operations will capitalize on the maneuver space afforded by the sea, rapid force closure through at-sea arrival and assembly, and the protection assured by the U.S. Navy’s control of the sea. C^sup 2^, combat support, and combat service support capabilities will remain at sea to the maximum extent possible and be focused upon supporting expeditionary air and land operations ashore. Forward deployed naval forces will have access to a responsive worldwide logistics system to sustain expeditionary operations. Seabasing will allow Marine forces to commence sustainable operations, enable the flow of follow-on forces into theater, and expedite the reconstitution and redeployment of Marine forces for follow-on missions.

Marine Air-Ground Task Forces

Marines typically deploy and employ as scalable, tailorable, combined arms teams known as MAGTFs. All MAGTFs, regardless of size, share four common organizational elements that vary in size and composition according to the mission: command element, ground combat element, aviation combat element and combat service support element. Organic to each MAGTF, regardless of size, are specialized antiterrorism and force protection capabilities that are available to support the JFC. Fully interoperable, each MAGTF will have the ability to serve as a JTF headquarters or as a functional or Service component commander of a JTF.

In partnership with the Navy, Marine forces will use the capabilities of bases and stations and selected naval platforms as “launch pads” to flow into theater. During deployment, Marine forces will conduct collaborative planning and execute en route mission training and virtual rehearsals. They will capitalize on shared situational awareness that is developed in support of the JFC and processed and distributed by the Supporting Establishment. These enhancements will revolutionize the otherwise timeintensive reception, staging, onward movement, and integration activities, allowing increased operational tempo and seizing early opportunities as the enabling force for the JFC. Forward deployed Navy and Marine forces will continue to be the JFC’s optimal enabling force, prepared to open ports and airfields and to establish expeditionary airfields and intermediate staging bases in either benign or hostile environments.

Marine Expeditionary Unit (Special Operations Capable)

The Marine expeditionary unit (special operations capable) (MEU(SOC)), in close partnership with the Navy, will continue to be the onscene/oncall enabler for follow-on Marine or joint forces. Operating forward deployed from the sea, the MEU(SOC) is unconstrained by regional infrastructure requirements or restrictions imposed by other nations. Because of its forward presence, situational awareness, rapid response planning capability, and organic sustainment, the MEU(SOC) will continue to be the JFC’s immediately employable combined arms force of choice.

The MEU(SOC) initiates humanitarian assistance, provides force protection, conducts noncombatant evacuations, enables JTF C^sup 2^, and facilitates the introduction of follow-on forces conducting limited forcible entry operations when required. These early actions shape the JFC’s battlespace, deter potential aggressors, defuse volatile situations, minimize the damage caused by natural disasters, and alleviate human suffering. Increasing mobility, speed, firepower, and tactical lift will enable this seabased, self-sustained, combined arms force to conduct expeditionary operations across the depth of the battlespace, in adverse conditions, day or night.

Marine Expeditionary Brigade

The Marine expeditionary brigade (MEB) is optimally scaled and task organized to respond to a full range of crises. Strategically deployed via a variety of modes (amphibious shipping and strategic airlift and sealift) and poised for sustainable power projection, the MEB will continue to provide a robust seabased, forcible entry capability. It will use organic combined arms and the complementary capabilities from the other Services-such as netted sensors, seabased fires, and advanced mine countermeasures-to locate, counter, or penetrate vulnerable seams in an adversary’s access denial systems. The MEB will then close rapidly on critical objectives via air, land, and sea to achieve decisive results. It can be used to enable the introduction of follow-on forces (joint and multinational) or be employed as an independent operational maneuver element in support of the JFC’s campaign plan. The MEB constitutes a multidimensional, seabased or landbased, operational “capability in readiness” that can create its own opportunities or exploit opportunities resulting from the activities of other compo, nents of the joint force.

Marine Expeditionary Force

As a crisis escalates, smaller MAGTFs and supporting units are deployed until a Marine expeditionary force (MEF) is in place to support the CinC. The MEF, largest of the MAGTFs, is capable of concurrent seabased operations and sustained operations ashore, operating either independently or as part of a joint warfighting team. The MEF can be tailored to meet multiple joint requirements with its inherent sustainability.

Specialized Marine Corps Organizations and Capabilities

Special purpose MAGTFs are non- standing organizations temporarily formed to conduct specif ic missions for which a MEF or other unit is either inappropriate or unavailable. They are organized, trained, and equipped to perform a specific mission such as force protection, humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, peacetime engagement activities, or regionally focused exercises. While the MAGTF construct will remain the primary warfighting organization of the Marine Corps, not all situations will require it to operate as a combined arms unit. Should the situation warrant, distinct MAGTF elements and capabilities may be employed separately in response to critical JFC requirements.

For example, the 4th MEB (Antiterrorism (AT)) is a unique organization with specialized antiterrorism capabilities. This unit consists of Marines and sailors specifically trained to respond rapidly-world– wide-to threats or actual attacks by terrorists. The 4th MEB (AT) contains the Marine Corps Security Force Battalion (fleet antiterrorism security teams), the Marine Security Guard Battalion, the Chemical/Biological Incident Response Force, and an infantry battalion specially trained in antiterrorism operations.

Supporting Establishment

Marine Corps bases and stations provide direct and indirect support to the MAGTF and other forward deployed forces and are the means by which Marine forces are formed, trained, and maintained. These bases and stations are platforms from which Marines project expeditionary power while supporting the quality of life of Marines and their families.

The Way Ahead

Marine Corps Strategy 21 identifies capability enhancements required to continue the evolution of the MAGTF. These capability enhancements include joint/multinational enabling, strategic agility, operational reach, tactical flexibility, and support and sustainment, which create a Marine force that provides the JFC with expanded power in order to assure friends and allies or dissuade, deter, and defeat adversaries. In accordance with our expeditionary culture and warfighting ethos, our doctrine, organization, education, and training must contribute to producing Marines and organizations that thrive in the chaos of conflict by:

* Producing leaders who have the experience to judge what needs to be done; know how to do it; and exhibit traits of trust, nerve, and restraint.

* Developing leaders and staffs who function in an environment of ambiguity and uncertainty and make timely and effective decisions under stress.

* Developing leaders by improving their capacity to recognize patterns, distinguish critical information, and make decisions quickly on an intuitive basis with less than perfect information.

* Enhancing leaders’ decisionmaking skills with investments in education, wargaming/combat simulation activities, and battespace visualization techniques within a joint or multinational framework.

We will see a convergence of transformation and modernization capabilities in our MAGTFs that will revolutionize expeditionary operations when currently planned programs mature. Realizing EMW’s full potential will require a developmental effort focused on improving C^sup 2^, maneuver, intelligence, integrated fires, logistics, force protection, and information operations. Achieving these improvements will require integration of both Navy and Marine Corps operational concepts, systems, and acquisition strategies.

Organization, Deployment, and Employment

Changes in operational and functional concepts may necessitate changes in the integrating concepts of organization, deployment, and employment. Organizationally, EMW emphasizes the MEB as the preferred midintensity MAGTF and the role of the Supporting Establishment in di- rect support of forward operations. Organizational structure must be mission oriented to ensure the effective deployment, employment, sustainment, reconstitution, and redeployment of forces. The Marine Supporting Establishment must be postured to facilitate situational awareness of worldwide operations, leverage information technologies, and exploit modern logistics concepts in order to anticipate and respond to MAGTF requirements.

Marines will deploy using any combination of enhanced amphibious platforms, strategic sealift and airlift, prepositioned assets, and self deployment options to rapidly project force throughout the world. By virtue of their en route collaborative planning and virtual rehearsal capability, Marine forces will arrive in theater ready for immediate employment. While Marines achieve great operational synergy when employed as fully integrated MAGTFs, the Marine Corps can provide specific forces and capabilities according to the needs of the JFC. Continuing our tradition of innovation, we must strive to enhance our concepts and technologies to organize, deploy, and employ the force.

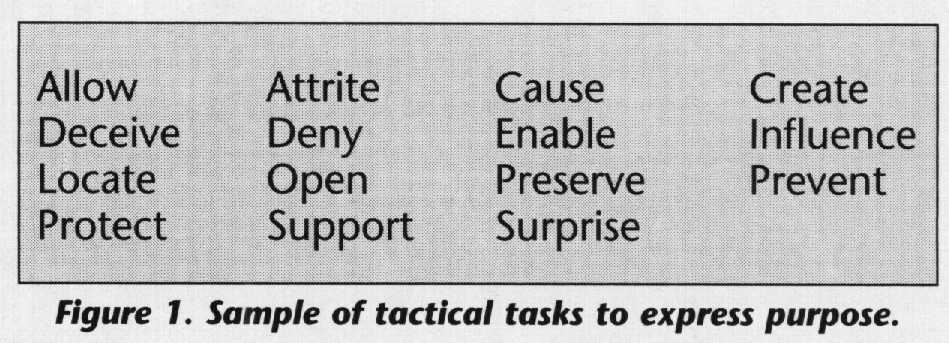

Maneuver

Maneuver in all dimensionsland, air and, uniquely, operational maneuver from the sea-enables commanders to exploit enemy weakness at the time and place of their choosing through the use of the operational mobility inherent in naval forces. Maneuver seeks to achieve decisive effects during the conduct of a joint campaign. It is the means of concentrating force at critical points to achieve surprise, psychological shock, and momentum, which drives adversaries into untenable situations. Maneuver can deny the enemy the initiative, reducing his choices to either defending the length and depth of the littorals, thereby dislocating his forces to the JTF’s advantage or exposing critical vulnerabilities to exploitation. Enemy forces reacting to MAGTF maneuver generate opportunities for the JFC to concentrate the complementary capabilities of other maneuver forces. Maneuver, integrated with fires, will be linked to and influenced by the JFC’s battlespace shaping operations and directed toward achieving operational effects. Innovative technologies will provide Marines enhanced mobility to cross greater distances and reduce the limitations imposed by terrain, weather, and access denial systems. The result will be an expanded maneuver space, both seaward and inland.

Enhancements in our

maneuver capability will compel adversaries to develop innovative anti- access strategies and systems. Proactive joint efforts to anticipate and counter current and future antiaccess systems will be criti- cal to ensuring freedom of action.

Integrated Fires

Fires involve more than the mere delivery of ordnance on a target. The psychological impact on an adversary of volume and seemingly random fires cannot be underestimated. The human dimension of conflict entails shattering an enemy’s cohesion through the introduct on ot tear and terror. Marines, applying the tenets of maneuver warfare, will continue to exploit integrated fires and maneuver to shatter the cohesion of an adversary.

We will increasingly leverage seabased and aviation-based fires and develop shorebased fire support systems with improved operational and tactical mobility. Streamlining our fire support coordination procedures and enhancements in combat identification techniques will support rapidly maneuvering forces while decreasing the risks of fratricide. Forces afloat and ashore require the ability to immediately distinguish friendly forces from others and to then deliver lethal and nonlethal fires with increased range and improved accuracy to achieve the desired effect. Volume and precision of fires are equally important. The continuous availability of high-volume, all-weather fires is essential for suppression, obscuration, area denial, and harassment missions. We will use fires to support maneuver just as we use maneuver to exploit the effects of fires.

Intelligence

Intelligence is a command function that optimizes the quality and speed of decisionmaking. EMW requires a thorough blending of the traditional domains of operations and intelligence. Commanders and their staffs must make decisions in an environment of chaos, uncertainty, and complexity, and they must be prepared to act on incomplete information. The goal of intelligence is to enable the commander to discern the enemy’s critical vulnerabilities and exploit them.

Intelligence must support decisionmaking by maintaining current situational awareness, monitoring indications and warnings, identifying potential targets, and assessing the adversary’s intent and capabilities at all levels of operations. This requires establishing an intelligence baseline that includes order of battle, geographic factors, and cultural information, all contained in universally accessible databases.

Deployed Marine forces will enhance their organic capabilities by accessing and leveraging national, theater, Service, and multinational intelligence through a comprehensive intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance network. The informed judgment of well-trained, educated, and experienced Marine analysts and collectors will remain the most important intelligence asset.

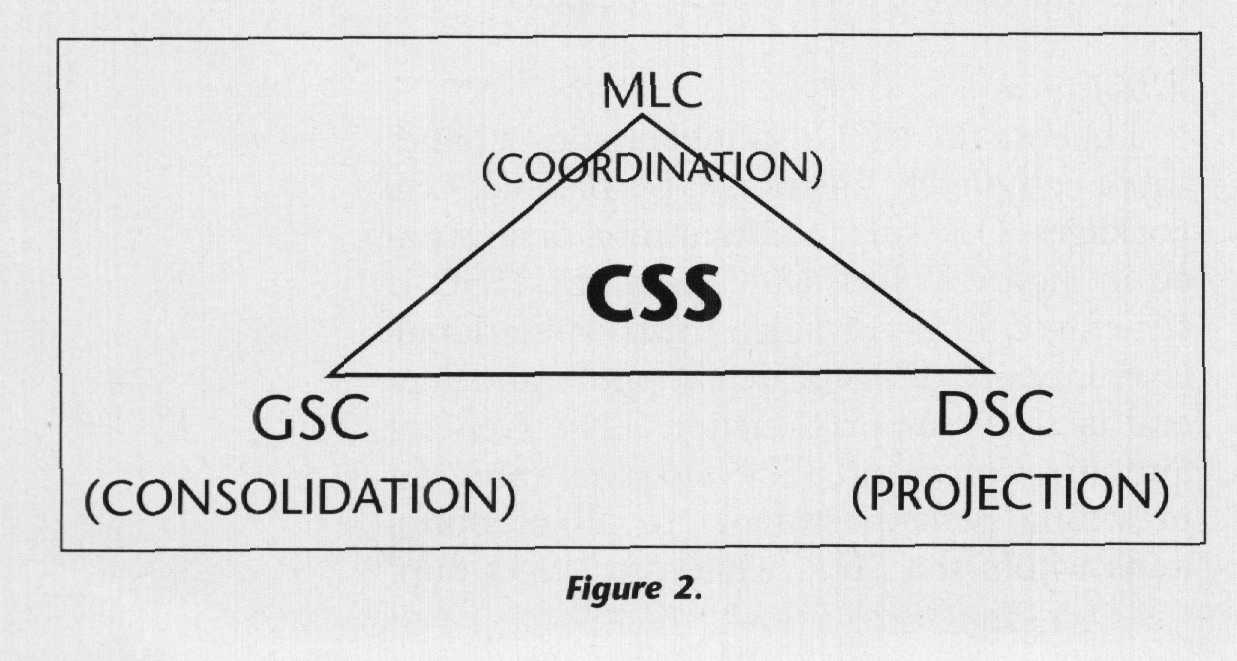

Logistics

Marines must access a worldwide infrastructure of distribution systems to support expeditionary operations. The integration of naval expeditionary logistics capabilities with joint information and logistics systems will provide total asset visibility and a common relevant operating picture, effectively linking the operator and logistician across Services and support agencies. Marines must explore ways to reduce the logistics footprint ashore through expeditionary support bases, seabased support, in-stride sustainment, reduction of consumables, improved packaging, better visibility over distribution, and development of alternafive ordnance variants that are smaller and lighter, but retain equivalent lethality.

Command and Control

EMW promotes decentralized execution providing subordinates latitude to accomplish assigned tasks in accordance with the commander’s intent. Organic and supporting C^sup 2^ systems and processes must be adapted to function in any environment, whether afloat, transitioning ashore, or on the move. C^sup 2^ must facilitate decentralized decisionmaking and enhanced situational awareness at all echelons. Concurrently, C^sup 2^ must provide the MAGTF commander the ability to direct joint and multinational task force operations when required.

EMW requires adaptable and intuitive C^sup 2^ architectures and systems that are fully interoperable with joint assets and compatible with multinational assets. Expeditionary forces will be able to access, manipulate, and use information in near realtime, developing a common tactical and operational understanding of the battlespace. They will have connectivity to theater and national assets and the ability to disseminate information throughout the force. This will support fully integrated collaborative planning efforts during both deployment and employment.

C^sup 2^ initiatives must address limitations in the capabilities of all amphibious platforms. Key factors include accelerated technological advances and rapid changes in equipment and capabilities. Flexibility, adaptability, and interoperability are paramount in the design and development of systems and platforms. Particular attention must be made to providing commanders with seamless C^sup 2^ capabilities throughout the battlespace.

Force Protection

Force protection is those measures taken to protect a force’s fighting potential so that it can be applied at the appropriate time and place. Force protection will rely on the integrated application of a full range of both proactive and reactive capabilities. Multidimensional force protection is achieved through the tailored selection and application of layered active and passive measures within all domains across the range of military operations-or warfighting functions-with an acceptable level of risk.

We will pursue improvements in the families of technologies and doctrine to enhance force protection capabilities. Marine forces will enhance security programs designed to protect servicemembers, civilian employees, family members, facilities, and equipment in all locations and situations. These enhancements will be accomplished through innovative technological and nontechnology-based solutions combined with planned and integrated application of antiterrorism measures, physical security, operations security, personal protection, and incident response.

Information Operations

Information operations involve actions taken to affect the adversary’s decisionmaking processes and information systems while ensuring the integrity of our own. The integrated components of information operations have always proven applicable across the full range of military operations. Information operations will be used to shape the strategic environment or impart a clearer understanding and perception of a specific mission and its purpose. Information operations will be a force multiplier-reducing the adversary’s ability to effectively position and control his forces-and prepare the way for the MAGTF to accomplish future missions. We must leverage information operations and ensure they are synchronized with the JFC’s campaign plan to achieve the desired operational effect.

Summary

EMW describes the Marine Corps’ unique contribution to future joint and multinational operations. As the Nation’s only seabased, forward deployed, air-ground force in readiness, Marines stand ready to support the JFC. Marines, intrinsically linked with naval support, maintain the means to rapidly respond to crises and respond with the appropriate level of force, MAGTFs are the JFC’s optimized force that will enable the introduction of follow-on forces and prosecute further operations.

EMW focuses our warfighting concepts toward realizing the Marine Corps Strategy 21 vision of future Marine forces with enhanced expeditionary power projection capabilities. It links our concepts and vision for integration with emerging joint concepts. EMW will guide the process of change to ensure that Marine forces remain ready, relevant, and fully capable of supporting future joint operations.