by Capt Andrew J. Graham

In the opening throes of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), the 3d Marine Aircraft Wing (3d MAW) employed its helicopter gunships in a unique manner for aviation assets, but a manner that the infantry battalion is very familiar with; a section of H-Is was tasked with direct support (DS) of a Marine battalion. Unlike a joint tactical air request (JTAR) time on station (TOS), the DS section was attached to the battalion landing team (BLT), and the aircrews’ 12-hour crew day was dedicated to DS of the battalion. Adapted to aviation counterinsurgency (COIN) operations, the DS section multiplied the combat power of Marine ground combat units.

The DS pilots and crew stood their strip alert at the battalion combat operations center (COC), awaiting tasking. If there was no tasking or if the unit was in a consolidation period, the aircrew returned to their base at the end of their crew day. However, if there was tasking, their physical presence allowed the battalion commander to instantly call on his own air support, without delaying the request through the JTAR process.

To clarify: the delay in support is not a problem when trying to get close air support (CAS) assets; this becomes an issue when requesting nonkinetic support. The battalion commander attempting to investigate time-sensitive intelligence beyond the reach of his ground units will be unable to compete with the more pressing requirements of troops in contact (TIC) situations, convoy and assault escort, or other CAS engagements in neighboring areas of operation (AOs).

In addition to giving the commander another tool to use in the MAGTF, the DS section allows Marine aviation units to support the MAGTF COIN effort in accordance with our Service philosophy of mission-based orders or individual initiative through commanders intent. An expansion of the JTAR process, and the next generation of four-bladed utility and attack helicopters, will enhance the utility of the light attack helicopter (HMLA) community and allow the supported element commander to greater dictate the tempo of his AO. This is achieved not through a change in tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) but by applying our doctrine of maneuver warfare in a more flexible manner.

To start with, we must ask, how does the Marine Corps apply aviation in maneuver warfare? And how do we apply maneuver warfare to aviation COIN operations? Filling the assault support and offensive air support roles of the six functions of Marine aviation, HMLA squadrons respond to requests for support either through preplanned or immediate tasking. The preplanned tasking takes the form of the JTAR to the tactical air command center (TACC), while immediate tasking is requested from the direct air support center (DASC). This is similar to a fire truck scrambling after the alarm bell rings at a fire department.

In both high- and low-intensity COIN operations, CAS plays a vital role in supporting the ground combat element (GCE). But in order to allow greater freedom for section leaders to influence the batdefield, the pilots need to be empowered through their other missions. (Independent action by aircrew requires detailed knowledge of the atmospherics of the local AO, friendly and enemy schemes of maneuver, and a list of actions automatically approved by the ground commander.) In the TTP outlined in the UH-I Navy TTP 3-22.3, UH-Is already teach tactics that allow intelligence collection and analysis. What they do not do is enable the pilot on the scene to act on that intelligence based on commander’s intent.

Even more than mechanized and motorized maneuver elements, aviation is perfectly suited to rapid retasking, taking advantage of shifts in tempo before the enemy can react. Currently the DASC performs this role and, under guidance from the TACC, will shift assets based on ground unit requests.

Ground forces spread across an AO have a lighter footprint the farther they push from the forward operating base (FOB). Air support multiplies their fire and maneuver, also providing direct responsiveness to the GCE commander, executing his intent. This completes our forces’ total orientation on the enemy and their state of mind. WTiat the DS section provides is an infantry patrol mindset in the skies, always searching to gain and maintain contact with the enemy. The true fruit that a DS section bears is in investigating time-sensitive intelligence. In a tenuous border region, the DS section allows the commander to investigate reports of smugglers crossing boundaries or guerrillas infiltrating the area of operations, without having to declare a TIC situation.

Philosophy

If maneuver warfare is a state of mind, how is our MAW adapted to maneuver warfare? Instead of applying mission type orders, are we just a combined arms force, essentially flying artillery and semitrailers? If I tell the subordinate what the commander wants, do I really allow him to determine how to accomplish it? At what level do I stop that? And what is my role in the overall plan? Providing utility support is not good enough; we must be able to identify what the enemy wants most, and then take it from him. If maneuver warfare’s goal is to shatter the physical and moral cohesion of the enemy, this goal can only be realized with an increase in operational tempo that the preplanned JTAR process slows.

In order to target the mind of the enemy, we must destroy his center of gravity, a concept in COIN that is one area with many nuances. For example, a guerrilla force survives with the support of the people either willingly or unwillingly. If the people are culturally xenophobic, and both the insurgent and counterinsurgent present bad alternatives, the people will support the local area leadership. Creative leadership at the junior officer level can affect this in innovative ways.

Maneuver warfare requires a shared responsibility for the success or failure of an operation. By giving the DS section to the BLT commander, the HMLA squadron becomes even more invested in the success of the ground unit. By working closer with the ground unit, the pilots will participate in the mission analysis and be able to recognize when the situation fundamentally changes. When it does, the pilots must be able to recognize that and provide the BLT COC with new courses of action.

Maintenance and Readiness

The DS section concept raises some unique logistical questions. Unlike DS support of tanks, amphibious assault vehicles, light armored vehicles, or artillery, aviation assets cannot perform their own operational-level maintenance. Does the battalion commander then require to be briefed by the maintenance material control officer on the status of the aircraft in phase maintenance? No. If fuel is available at the FOB, there is no footprint requirement that cannot be satisfied by returning the aircraft to the parent airfield at the end of the crew day, being replaced by another section with fresh pilots and aircraft. At the end of the DS JTAR, the DS section returns to the parent squadron, and operational-level maintenance is performed by the squadrons maintenance section.

The DS section concept does not necessarily need to be provided entirely by helicopter gunships. The proposed armed variant of the MV-22 will supposedly be capable of self-escort, allowing the maneuver battalions greater freedom and speed of movement on the battlefield. A DS section of F/A-18s cannot provide the quick reaction force (QRP) capability, but it can still provide dedicated forward air controller (airborne); nontraditional intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (NTISR); counterimprovised explosive device (IED) search; and CAS beyond the limitations of a JTAR requested TOS.

Marine Corps Wirftghting Pubi i cation 3-2 (MCWP 3-2), Aviation Opera rions, states that:

. . . with the designation of an aviation unit to the direct support role comes the requirement to establish direct liaison, direct communications to receive critical information, coordination of local security, and logistic support from the supported unit.1

These requirements are easily fulfilled by using the pilots to establish direct liaison and by normal communications between the aircrew, the COC, the BLT, and the squadron commander. Local security is provided by perimeter security at the FOB, and logistical support comes in the form of food, water, and aviation fuel. All ordnance and maintenance is provided at the parent squadron’s headquartered airfield once ordnance has been expended. Some ordnance can also be prestaged at the FOB, but this would likely exclude precision guided munitions (PGM).

The forecast impact of DS section requirements on maintenance and readiness is minimal. In Iraq an HMLA with an 18 Cobra/9 Huey mix was commonly responsible for a main body at the larger airfield and a detachment at the smaller FOB. The detachment provided a CAS section and medevac chase 24 hours a day, continuously. The main body of the squadron provided two mixed sections for CAS and three Cobras for the medevac chase, again 24 hours a day, continuously. The pilots and aircrew maintained 12-hour shifts, flying between two and four JTARs per shift. Shifting the CAS responsibility from one section and sending them to provide DS would have no impact on the maintenance requirements for the aircraft, provided that the DS section is sourced from the main body and not from the detachment. The DS section can always be diverted to CAS in case of emergency; however, with low-intensity COIN operations, retasking the second CAS section to DS aids the BLT commander in shaping his battlespace. Squadrons in Iraq have proved that this level of operations can be maintained, with very few exceptions, for the duration of a 7-month deployment. Based on this model, I present the following scenario.

Scenario

A BLT commander has a large AO, almost 50 square miles. The area includes 1 town of 15,000 people, 3 villages of 6,000 people, mountainous terrain over riie southern portion, and large open desert between the northern towns. The local population varies from accepting the American presence to indifference to overt hostility. There is an experienced and aggressive guerrilla force conducting a grassroots insurgency campaign. The BLT has been tasked with eliminating their influence in the AO in order to spread the a uthority of the legitimate host-nation government. There is low threat to air and high threat to ground forces from IEDs. The BLT commander allocates his forces as follows:

* Company A is responsible for the main town.

* Company B opera tes from the pa trol base sending out squa d-sizedpa trois for 1 to 2 days at a time in the northern desert.

* Company C divides the pia toons between the three villages and runs combined action platoon patrols in and around the area with the local national police, sometimes (but not always) winning hearts and minds but providing constant presence and pressure on the enemy grassroots campaign.

* Weapons company (QRF/combined antiarmor team (CAAT) Aight armored reconnaissance section) actsasa maneuver element but provides mounted patrols covering the open areas between the towns.

* Reconnaissance platoon/surveillance target acquisition section provides an independent maneuver element, conductingraids based on actionable intelligence but, except for extreme circumstances, does not participa te in QRF opera tions.

* DS strip section provides two 12-hour shifts to provide 24-hour support outside die JTAR process. One AH- 1 and one UH-I provide PGM, armed reconnaissance, assault support, NTISR, urgent casevac, and CAS capabilities within 50 nautical miles.

Now, without a JTAR, the DS section provides the BLT commander with NTISR, on-call leader’s reconnaissance, movement, aeroscout-type QRF capability, humanitarian assistance/disaster relief Un capability, and ail other aspects of the six functions of Ma ri ne aviation.

Here, is a bad day. After days of heavy fighting, weapons company is down to 20 percent of its mortar reserves, and PFC Jackson from Company A needs a root canal. Early in the morning, the DS section transports Jackson to trie BLT headquarters and the battalion aid station, and Jackson and the mortar resupply are returned to the field before the end of the day without the trouble of putting a convoy together and risking IED a tracks.

After die DS section returns PFC Jackson to Company A, they support Company B with aerial reconnaissance, until Company A encounters a TIC situation. This causes the Company A commander to con ta a the fire support coordination center to request air. While Company A conducts a firefight with guerrillas in the town square, t/ie battalion air officer (Air O) redirects the DS section from Company B to Company A. The section will have faster reaction rime than a strip alert section beca use they will a I rea dybea irborne. While the DS section finishes its fuel and TOS, the Ai fO coordinates with DASC (or follow-on support. When the DS section runs out of gas, a preplanned on-call section relieves it. Meanwhile, the DS section returns to the FOB to refuel and rearm, and if Company A still needs air support, they can relieve the CAS section or remain at trie FOB for follow-on tasking.

While on pa trol, a pia toon from Company C finds a child with a broken leg. The injury is not life threatening but is painful and devastating to me child’s parents in the village. Sgt Smith, the patrol leader, contacts the compa ny FAC who requests the DS section from the AirO. The DS section arrives; the child and her parents are loaded onto the Huey. They are taken to the battalion aid station where she is treated and then all are returned to die village. This would be painful and nearly impossible to do by ground transport. If the villagers respond in a positive way it is a bonus. Helping the locals is the morally responsible thing to do and supports the saying, “first, do no harm.”

In the late afternoon, guerrillas storm the police station in the large town, executing the policemen and taking their weapons and equipment. As weapons company launches the CAAT team and the ground QRF, the battalion AJrO launches tAe DS section to provide overhead on the scene. After pushing overhead, the DS section spots a convoy of civilian vehicles exiting the town at a high rate of speed. The convoy consists of several vehicles with covered equipment in the back lea ving the town toward the open desert. The DS section sees the men in the vehicles and suspects their covered vehicles contain the stolen police weapons. The Cobra pulls into a hover hold, halting the convoys departure, while the Huey establishes a position to the rear of the convoy to prevent any escape. The a i reran remain on the scene until the ground QRF arrives to search the convoy. (With a Yankee Huey, the DS section can execute NTISR with a fire team on board, providing instant QRF.) Finding the police weapons, the QRF takes all of the drivers prisoner but does not ha ve room for all of the prisoners in its HMMWVs. The QRF loads several prisoners in the DS Huey and destroys the vehicles in place. The DS section returns to the FOB with the prisoners to pick up reinforcements for the QRF or resets as directed by the ba ttalion AirO.

This scenario shows the BLT spread thin, not uncommon in realworld COIN operations. Yet the battalion’s varied operations, and the speed and maneuver provided by the mechanized and aviation assets, deny the enemy a center of gravity and afford him no place to rest or retrofit in the open. It forces the enemy to react to our will.

Command Relationships

The DS section will be under tactical control (TaCon) of the BLT commander, because the squadron commander retains command over squadron aircrew and airframes. (The squadron commander retains operational control.) However, TaCon still provides the BLT commander with the authority to direct the DS section for the duration of that 12-hour JTAR.

MCWP 3-2 defines DS as:

. . . a mission that requires a force to support another specific force and authorizes it to directly answer the supported force’s request for assistance (e.g., an attack squadron in direct support of one subordinate unit of the GCE).2

DS differs from close support in that close support is:

. . . the action of the supporting force against targets or objectives that are sufficiently near the supported force. This close proximity requires detailed integration or coordination of the supporting action with fire, movement, or other actions of the supported force (e.g., aviation units providing CAS to units in contact).3

DS is preferred over close support because the tasking is not based on a specific target or mission set but because the fluidity of COIN operations necessitate taking advantage of the varied capabilities of the aviation platform.

As a whole, Marine Corps aviation is usually in general support of the GCE because there are usually finite aircraft to meet infinite requests for support. General support:

. . . allows Marine aviation to fight or to provide support throughout the MAGTF area of operations and allows the most efficient and effective allocation of aircraft to the MAGTF. This process is orchestrated through the air tasking cycle, allowing flexible and prioritized tasking.4

MCWP 3-2 clearly states that:

. . . the command support relationship established for the ACE [aviation combat element] by the MAGTF commander is almost always in general support of the MAGTF. . . . Since availability of aviation assets for mission tasking rarely meets the demand, the MAGTF commander keeps the ACE in general support of the MAGTF. . . . By using and completing the air tasking cycle, planners can ensure that finite aviation assets are allocated to achieve maximum effect with correct prioritization based on the main effort.5

If aviation assets are finite, how do we find enough to make the DS section a supportable concept? While there are limited assets available, they are often augmented with joint and allied aircraft. The decision to dedicate a DS section for 12 hours to one battalion’s AO is made with the knowledge that the force multiplication given to one BLT’s AO provides more benefit to the overall mission end state than by spread-loading aviation assets in general support across the theater.

Conclusion

The DS section would still be requested using the JTAR process; however, instead of a specified TOS, the JTAR would request 12-, 24-, or potentially 48-hour support. The aviation squadron commander is responsible for the maintenance and safety of his pilots and aircraft, while the battalion commander would have launch authority under very specific guidelines. As a component of the air tasking order, the DS section is not a revolutionary concept. However, as far as driving the aviation capabilities and decisionmaking process further toward the ground commander, it is a vast departure from the normal process.

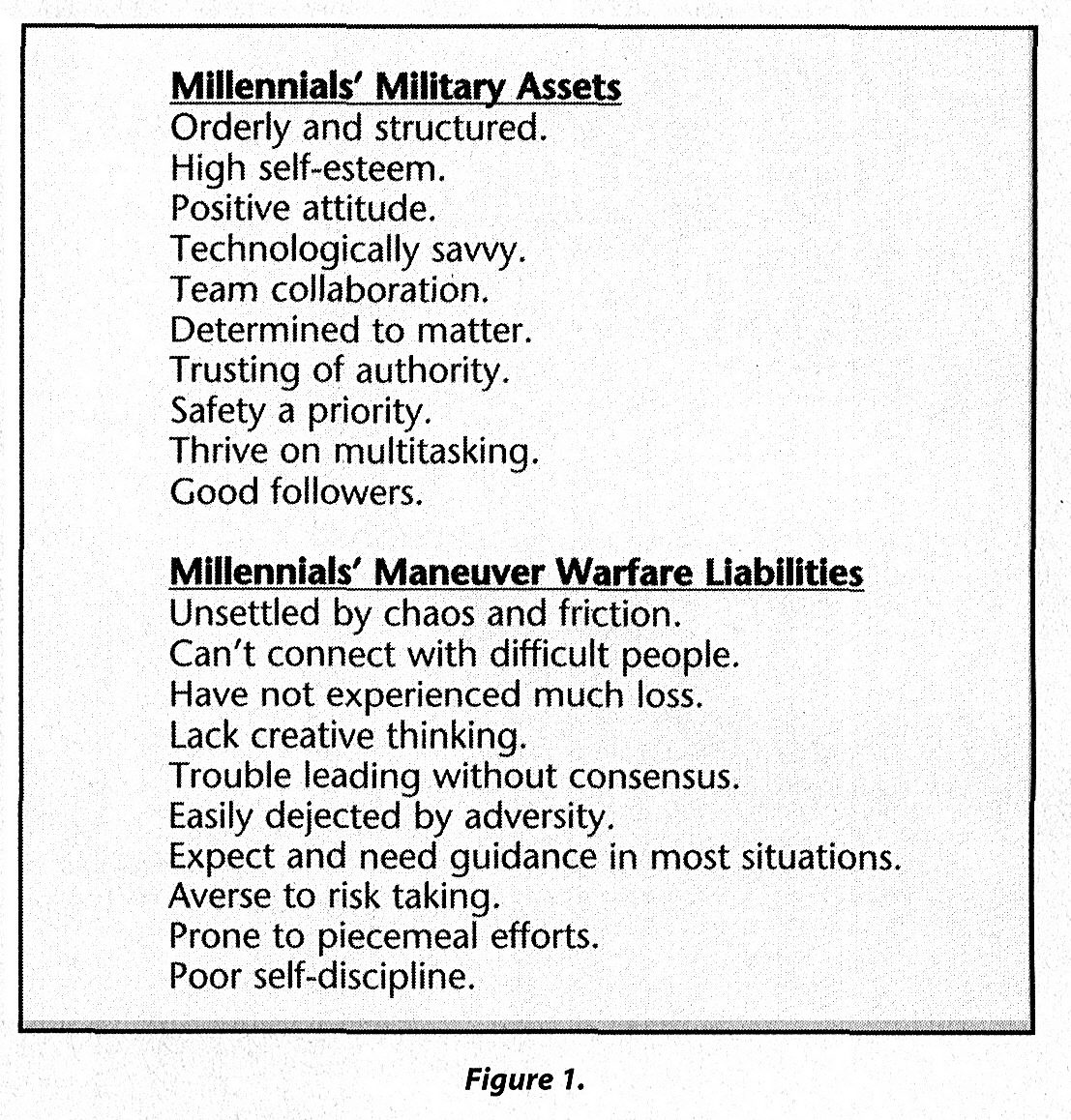

Real application of maneuver warfare requires courage and acceptance of risks. In the infantry this means empowering the junior noncommissioned officer to make important decisions, literally the “strategic corporal.” The aviation battlefield equivalent is the pilot, usually a captain or major, senior to the corporal but still a Marine whose actions can have both tactical and strategic consequences. In the MAW this means more than acceptance of risk; real acceptance means that we will take battle damage, lose airplanes due to hostile fire, and suffer casualties alongside the Marine ground units we support. Current safety climates are opposed to these as a metric for a successful command, but if battlefield success is the metric by which we judge a successful command, then we need to accept the risk that might lose a garrison safety award. A commander who accepts this risk will allow his people greater freedom to operate and succeed based on their initiative. The DS section allows our ground commanders greater flexibility and dominance in their AOs. Adapted to aviation COIN operations, the DS section will multiply the combat power of Marine ground combat units.