Maneuver Warfare Roadmap: Part I: Trends and Implications

Posted on July 22,2019Article Date Apr 01, 1982

by Col Bruce G. Brown, USMC(Ret)

A number of articles have appeared in professional magazines over the past two years or so which constitute a refreshing refocus on the art of war. Maneuver warfare and the Boyd Theory are in the “spotlight” of this dialog. The purpose of this article is to stimulate further thought on the tactical implications of a maneuver style of warfare as applicable to the landing forces of the Fleet Marine Force (FMF). It is presented in two parts. Part I deals with doctrinal implications and force structure/task organization trends believed to be inherent in any adoption of maneuver warfare concepts. Part II will attempt to portray those trends in terms of concepts of employment and tactical applications in amphibious warfare.

It is also noted in introduction that the terms “maneuver warfare” and “Boyd Theory” are sometimes used as “buzz words” (words or phrases that become popular primarily because nobody within hearing knows what they really mean). The point is that the maneuver style of warfare and Boyd Theory are important to the Marine Corps. That they are also elusive at this stage of their development is one of the primary reasons for writing this article.

A Point of Departure

The basic literature on maneuver warfare is contained in contemporary professional publications and military history. Specifically, the Apr81 issue of the Marine Corps GAZETTE is of particular interest to Marines, and it is not believed necessary to review that issue or other writings here. However, it is appropriate to have a consensus on a point of departure relative to the fundamentals of a maneuver style of warfare. As this is written, the basic dichotomy in the dialog focuses on the psychological aspects of maneuver warfare theory as advanced by Mr. William S. Lind. It is very difficult for most Marines to embrace that aspect at the tactical level.

However, it is not necessary to embrace the psychological aspect (or discard it) at this time. What is necessary is agreement that at least some of the fundamentals offer the beginning of a path toward tactical applications through which one can fight outnumbered and win. Therefore, let’s start with the Marine Corps’ current perception of the fundamentals as the only logical point of departure. This perception is currently contained in Operational Handbook (OH) 9-3 (Rev A), Mechanized Combined Arms Task Forces (MCATF), March 1980, and Education Center Publication (ECP) 9-5, Marine Amphibious Brigade Mechanized and Countermechanized Operations, 20 January 1981.

Table 1 depicts extracted portions of the basic tenet of these documents. Note that they exclude direct focus on the psychological aspect. With all due respect to Mr. Lind, this exclusion is believed helpful at this time, due to the nature of the dichotomy. It is critical to get more Marines embarked on USS Maneuver before it leaves port. Ah abandon ship drill during the embarkation phase would be disastrous-the doctrinal Marine alternative may not be firepower-attrition; it may better be described as adherence to frontal assault tactics. Also, keep in mind that maneuver warfare in the Marine Corps will be a unique style, built by Marines, for Marines-a style that will fit Marines.

Doctrinal implications

As used herein, doctrinal implications include basic contrasts, believed to be explicit or implicit, between the fundamentals of maneuver warfare as depicted in Table 1, and codified doctrine, tactics, and techniques reflected in current Landing Force Manuals (LFMs) and Fleet Marine Force Manuals (FMFMs). Not all contrasts are included, only the basic or more obvious. Collectively, they constitute an indictment of current doctrine and a challenge to change it.

* An amphibious forcible entry operation is an attack launched from the sea-it is not an assault and should contain no phase with that title.

* Frontal attack and assault are the antithesis of maneuver warfare. Frontal attacks are to be avoided; you hold (or delay, or withdraw) in front of the enemy, you attack his flank and rear. Assaults, when used, are not only conducted on a flank or rear, but should be conducted with something near a 10:1 force ratio advantage vice a 3:1 ratio, and should be conducted against hasty-vice-prepared defenses. Prepared defenses are to be avoided like the plague-bypassed, left stranded-or the enemy must be enticed to leave them.

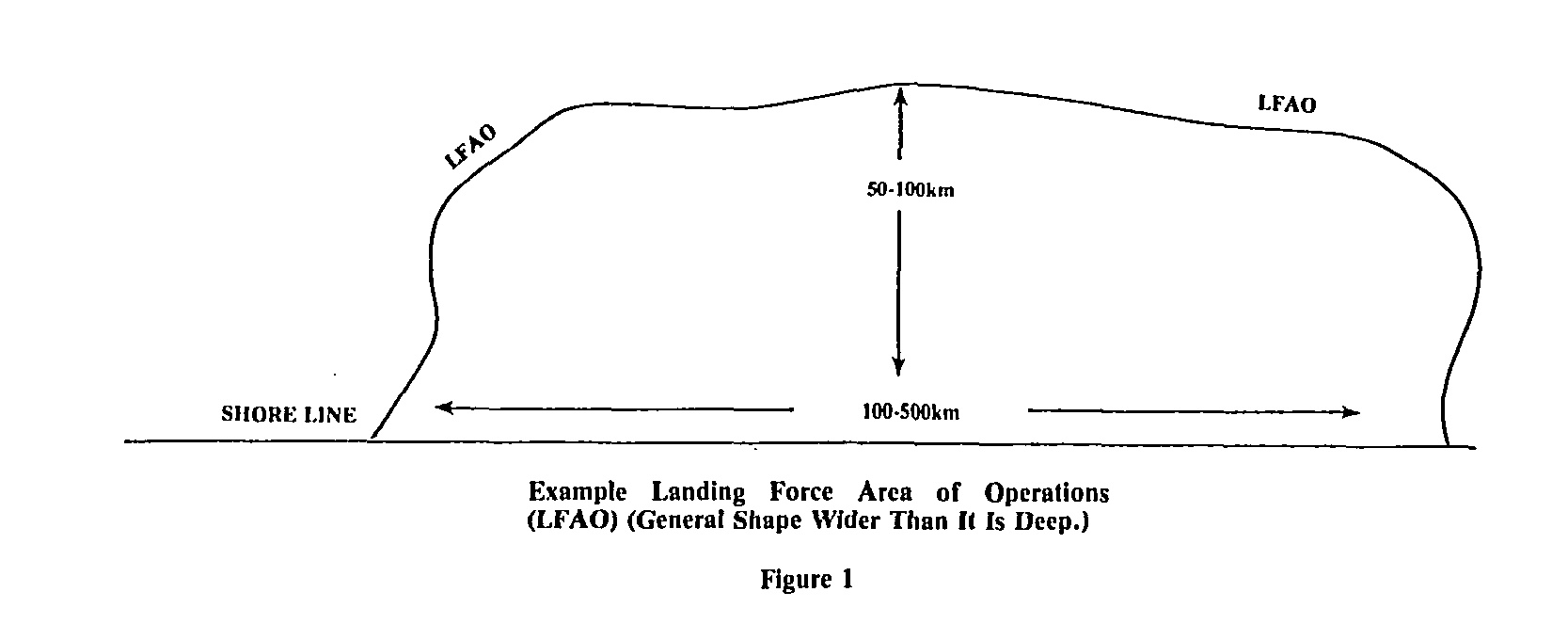

* The force beachhead line (FBHL), normally drawn from a trace of the final terrain objectives of the landing force, is not applicable to the conduct of a maneuver style of warfare by landing forces. It must go. Also, the advent of the vertical envelopment concept (how many years ago?) and now the landing craft, air cushioned (LCAC) make the term beachhead obsolete. The lodgment is by no means a beachhead and, in the context of maneuver warfare, is much better defined as a landing force area of operations (LFAO).

* The shape and size of the LFAO should be influenced by maneuver warfare concepts. Obviously, the size will vary significantly between different types’ of missions, threat forces, and between different-sized MAGTFs. However, it is believed the general shape will be constant; that is wider than it is deep. There are many reasons for this, but the primary ones relate to the umbilical cord to the sea. The Navy portion of the amphibious task force (ATF) remains a vital part of the maneuver concept and capability throughout the operation. Deep inland thrusts stretch the umbilical cord to a point where the landing force ashore becomes ineffective no matter what tactics are employed. However, operations along the littoral do not stretch the cord. They take full advantage of assets at sea such as naval gunfire (NGF), LCACs, and helicopters. (See Figure 1.)

* Maneuver warfare by ATFs and landing forces (LFs), combined with real world deployment and mount-out techniques, mandates a basic doctrine wherein the ATF and LF missions are assumed to be received while afloat, not prior to embarkation.

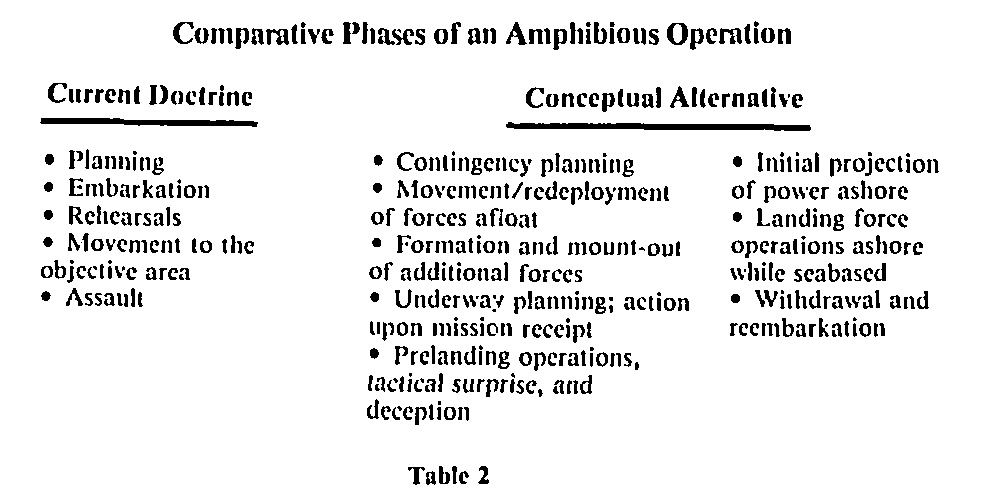

* Rehearsals after receipt of the forcible entry mission are to be avoided if possible. Exceptions to this general principle would be rehearsals to deceive the enemy. For a comparison of potential phases of future amphibious operations with contemporary phases, see Table 2.

* Recon-pull tactics are critical to the initial projection of power ashore. If the commander amphibious task force (CATF) and commander landing force (CLF) are not confident of “landing where they ain’t,” they simply feint until they are confident.

* Once a CATF and CLF are confident of “landing where they ain’t,” the initial projection of power ashore is a coordinated, command-push operation designed to facilitate initial maneuver, security, and the resumption of recon-pull tactics ashore as soon as feasible.

* Fixed installations, particularly aviation facilities, logistic facilities, and large semifixed command posts (CPs), cannot be phased ashore in a maneuver style of warfare. If frontal attack and assault constitute the antithesis of maneuver warfare on the tactical side of the house, then fixed installations ashore constitute the corollary on the support side. (Please do not begin to rebut this with preconceived bias related to the inevitability of “subsequent operations ashore.”) During the entire amphibious operation, to the last minute before termination, the LF must be free to maneuver unhampered by a rear area jammed with fixed installations. In addition, fixed installations are easy targets for a numerically superior enemy force regardless of who has air superiority. The entire theme of pushing command and control, aviation, and logistics facilities ashore is ludicrous in the context of a maneuver style of tactics. The adage should be to keep them afloat where they are mobile and much more likely to survive and perform their basic functions.

The magnitude of this basic (incomplete) list of doctrinal implications suggests that it is foolish to expect an immediate, or “miracle” LFM on maneuver warfare. This is not intended in any way as a “put-down” of Capt G.I. Wilson’s excellent article in the April issue; it simply means we need a deliberate and comprehensive approach to the challenge. A rapid, frontal assault on the doctrine will only result in inconsistency at best, and chaos at worst.

Force Structure/Task Organization Trends

Three force structure trends implicit in maneuver warfare directly affect the ground combat elements of landing forces. Two of these are apparent trends, the third is less obvious:

The first trend is toward the heavy mechanized combined arms task force (MCATF). Although this is an obvious development, it is still far from complete in concept, programming, or training. It is obvious because, until the tank becomes obsolete, a heavy tank/mechanized capability is required to provide the shock/exploitation action associated with main attacks. It is simply a capability needed to sustain the offensive flavor of an amphibious forcible entry operation against a mechanized/mobile enemy force. The MCATF is a task-organized, tactical entity, built primarily around tanks, mechanized infantry units, and self-propelled artillery, all of which are not helicopter transportable. However, it is still only a trend. This is best illustrated in a MAF level amphibious operation wherein a surface-landed RLT should be fully configured as a MCATF. Remember the definition. It is a mechanized combined arms task force; it is not a mobile task force plus supporting arms.

The second apparent force structure trend is the light armored task force (LATF) concept. Exactly where this trend will wander is unclear at this time. Also unclear is whether the LAV family development will be primarily targeted on nonamphibious or amphibious tasking. The Marine Corps has been placed on the horns of a programming dilemma due to the nature and timing of the nonamphibious tasking related to the MPS concept. The near-term concept places a duplicate set of scarce (inadequate) LVT assets aboard the deployed ships. It is not possible to bring an LATF brigade, equipped and trained, into the force structure as the basis of a 1983 MPS brigade. Therefore, the 1983 MPS brigade will also involve the LVT in further nonamphibious tasking with duplicate equipment sets. The temptation to program LATFs for dedicated, nonamphibious tasking (MPS and/or strategic airlift) is almost irresistible in order to swing the scarce LVT assets back to an amphibious mode. The problem may be further complicated by an institutional fear that programming the LAV family development in other than a nonamphibious/strategic airlift mode might place the development in direct competition with further LVT development.

Despite these complications, it is believed that the Marine Corps should anchor its LAV family development under its Title 10 charter-namely, amphibious warfare. The LATF and LAV family development are crucial to landing force capabilities in a maneuver style of warfare. In amphibious operations, the LATF is needed to complement and enhance the effect of an LVT/tank-configured task force. Given that about one-third of a MAGTF would be fully mechanized as a heavy MCATF, it is obvious that the MCATF alone could not sustain the offensive posture of an amphibious operation against a mechanized/mobile enemy.

The fundamental purpose of the LATF in amphibious forcible entry operations is to combine the vertical envelopment capability with a highly mobile, two-dimensional envelopment capability in order to maintain constant and confusing pressure on the flanks and rear of a very mobile and numerically superior enemy force. Given sufficient L-AV family assets to form several LATFs at the regimental level, the flexibility of the LATF, in size and weight, would give the Marine Corps additional rapid deployment capabilities related to strategic airlift. This flexibility may obviate the requirement for excessive nonamphibious ship building under the MPS concept-but its logical, primary purpose is in amphibious forcible entry.

The third trend implicit in a maneuver style of warfare is foot-mobile infantry. First, an adequate definition of the term may be required because some confusion has apparently developed over time with respect to what these people do best and what they cannot do very well at all. What they can do very well is operate both offensively and defensively in restricted terrain (mountains, jungle, and built-up areas). However, to be effective in these environments, foot-mobile infantry must be truly tailored for those environments. They must not be roadbound in jungle or mountainous terrain-not encumbered with organic weapons systems they cannot maneuver in built-up areas. The definitional focus here then is on infantry battalions that are exclusively foot-mobile/man-pack outfits.

In order to emphasize the point of foot-mobile infantry as a trend implicit in a maneuver style of warfare, let us take time to reflect upon the foot-mobile infantryman in his purest form:

* He can climb mountains, scale and rappel cliffs, maneuver on ridgelines inaccessible to “standard weapons sytems.”

* He can move crosscountry through swamps and jungles, maneuver through dikes and paddies.

* He does not need roads, in fact, he avoids them because he knows they are enemies, not friends.

* He can enter buildings from their roofs, open large vents, open doors/windows, climb/descend staircases, rappel down elevator shafts.

* He can move from doorway to doorway, move across or down railroad tracks, move across or through parks, climb fences, enter and move through sewers, etc.

* He consumes no fuel and expends very little ammunition.

* He is easy to insert and extract tactically by helicopter-he is easy to resupply exclusively by helicopter.

What he obviously cannot do very well is attack tank-heavy mechanized forces on their turf. Give him enough antitank assets, and he can defend well against those forces on his turf, but not really well on their turf. The point is that the contemporary infantry battalion is not structured or tailored for its original purpose and greatest strengths. Therefore, the maneuver style of warfare implies a trend toward a truly foot-mobile capability, applicable to landing force operations wherein restrictive terrain is a significant factor in success or failure.

Three additional trends are crucial for other elements of the landing force if maneuver warfare capabilities are to be enhanced. First is the trend toward the heavy-lift (CH-53E) helicopter as the primary transport helicopter in amphibious operations. This trend is illustrated by the procurement of M198 artillery in direct support battalions and by the LAV development. Either the HXM must be capable of lifting the M198 and the LAV, or the CH-53E program must be greatly increased. When related back to standard infantry, we must forget the “crowd killer syndrome” and learn to fly and land “where they ain’t,” with greater tactical integrity, over a shorter period of time.

The second trend is the requirement to place dedicated helo assets (attack and transport) in direct support of separated and maneuvering ground units.

Third, the doctrinal implications, as addressed, drive combat service support and landing support to seabasing. What is needed is a concept to support amphibious operations (no subsequent operations ashore) that will fit on the amphibious shipping expected to be available.

Conclusion Part I

The Marine Corps traditionally has contained a standard infantry battalion; i.e., all 27 infantry battalions are programmed to be mirror images. Fluctuations in the structure have been made across the board (three- or four-company battalions, with or without a weapons company). However, in recent years micromanagement techniques required to cope with constrained manpower have caused the infantry battalions to be less than mirror images in real life (e.g., manning levels, reduced “R” series T/Os). Also, in real life, the fleet assistance program (FAP) changes the composition of the battalions as they rotate into and out of unit deployment cycles. The differing trends outlined above, seen in conjunction with constrained manpower and the “facts of life,” suggest that a new approach to structuring the infantry be considered. Specifically, it is believed that if a number of battalions and regiments are tailored to each of the three infantry trends addressed, the Marine Corps would achieve a more effective force for each capability desired in the total force structure. It is also believed that rigid adherence to the concept of a standard battalion, amidst these developing trends, will inevitably result in more manpower (and equipment) than is needed in the total structure-the “standard” battalion is less effective in any one mode and less efficient in all modes.