Maneuver Warfare in Cyberspace

Posted on August 05,2019Article Date Oct 01, 2018

by Capt Brian R. Raike

“Maneuver warfare is a warfighting philosophy that seeks to shatter the enemy’s cohesion through a variety of rapid, focused, and unexpected actions which create a turbulent and rapidly deteriorating situation with which the enemy cannot cope.”1

The concept of maneuver warfare has been studied in all domains and is a foundation that guides the way the Marine Corps conducts operations. Retired Air Force Col John Boyd studied the subject regarding air-to-air combat and then translated it to fit conflict in all domains. According to Col Boyd, to outmaneuver an enemy, one must create a greater relative tempo of operations.2 This is true in all domains of warfare. Historically, during conflict, one side’s militarization of a new domain and the other side’s failure to militarize that domain results in a decisive victory for the former and a devastating loss for the latter within that domain. However, as Dr. James Lacey of the Marine Corps War College stated, “Losing in one domain does not equal defeat.”3 While it is true that losing in one domain does not equate to losing a battle, campaign, or war, cyberspace tends to underpin most of the other domains on the modern battlefield. As such, the United States and its allies cannot afford to be outmaneuvered in this space.

The decentralized command and control (C2) of operations enables effective maneuver warfare.^ To create this decentralized C2, the joint community has developed battlespace coordination measures and fire support coordination measures (FSCMs) that govern deconfliction requirements for air, ground, and sea operations. Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Operations, addresses the cyberspace problem statement by stating that cyberspace operations require “coordination, cooperation, and a comprehensive approach to achieve common objectives.”3 While joint doctrine addresses a need for this comprehensive approach, it does not prescribe a method by which the Services may achieve this end.

Cyber Battlespace

To enable tempo in military operations across multiple domains, the joint force uses boundaries and control measures. Specifically, commanders “establish various maneuver and movement control, airspace [coordination], and fire support coordination measures to facilitate effective joint operations.”6 The joint force employs these concepts in the air, sea, and land domains; this can be done in cyberspace as well.

The cyber battlespace is essentially composed of the infrastructure, systems, and protocols that make up the Internet. However, it is important that we standardize the way in which we view these elements. By understanding the interrelatedness of cyberspace, we may be able to leverage existing boundaries to institute controls that allow for processes similar to traditional battlespace C2 and deconfliction.

Cyberspace, without defined boundaries, is akin to a map without military graphics, markings, or sector delineations. Autonomous systems, designated by numbers in shared databases (known as ASNs), are interconnected, high-level routers and switches that connect to other networks over physical cables. Large organizations, such as Internet service providers, own and operate ASNs and conduct the intra-domain routing of packets using the language of border gateway protocol.7 Large international backbones carry data over vast distances between ASNs. Large networks may also connect via satellite links using radio frequencies. Once the data reaches a regional gateway, network access points convert the data to the format of transmission control protocol/Internet protocol (TCP/IP). Subordinate to these large networks are smaller networks known as widearea networks and local-area networks, which use TCP/IP to send and receive data, known as inter-domain routing. To reach its final destination, data may ride over multiple methods of transportation, including radio waves and microwaves. The client/server methodology used by TCP/IP allows data to travel to the appropriate destination via routers using interior gateway protocols and provides the appropriate data type based on the server used to deliver the data.

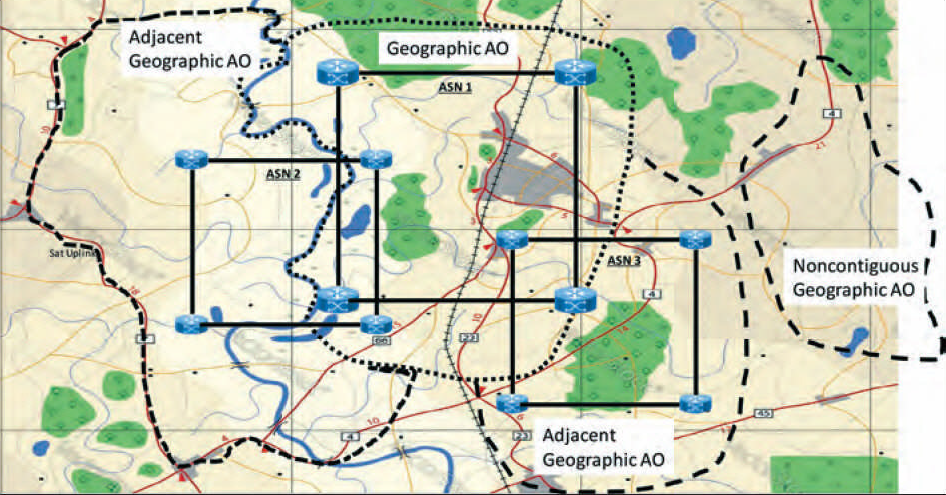

Using the inherent boundaries depicted above, cyberspace can be broken down into areas of operations (AOs) and assigned to military commanders, who can conduct supporting operations to military actions within their geographic AO. In joint doctrine, the joint force commander assigns AOs to his subordinates as a means to enable subordinate commanders to “accomplish their missions … and protect their forces.”8 Similarly, in cyberspace, a cyber-AO (C-AO) may be defined as the logical space and physical routing devices, transmission paths, and network components which may impact the applicable geographic AO. The starting point for defining the C-AO is to determine which ASNs impact the geographic AO. By listing these ASNs, one may understand the larger inter-domain routing pathways that impact the physical AO. The ASNs, which communicate via border gateway protocol, essentially become the outer boundary of the C-AO. Border gateway protocol ıs a path vector protocol, which means that it maintains a specific path for data flow. This is particularly useful in establishing the C-AO because a reading of the protocol at a given point allows one to infer which ASNs connect to the ASNs that directly impact the geographic AO. The associated IP space confining these ASNs makes the first element in the C-AO. (See Map 1.)

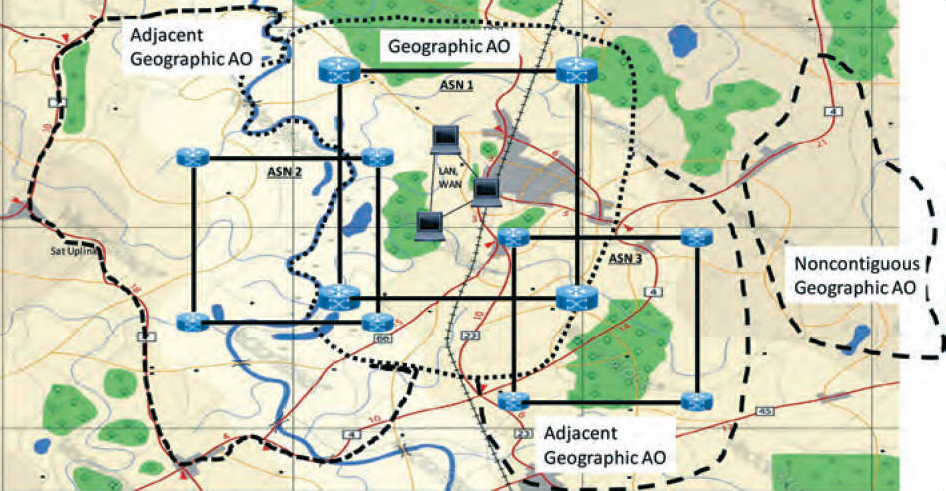

An analyst may define the intra-domain atmosphere after discovering the ASNs that may impact the geographic AO. Specifically, he must discover which networks are subordinate to each individual ASN. These subordinate networks are the wide-area networks and the local-area networks. One may identify these subordinate networks through a combination of open-source and intelligence community resources. (See Map 2.)

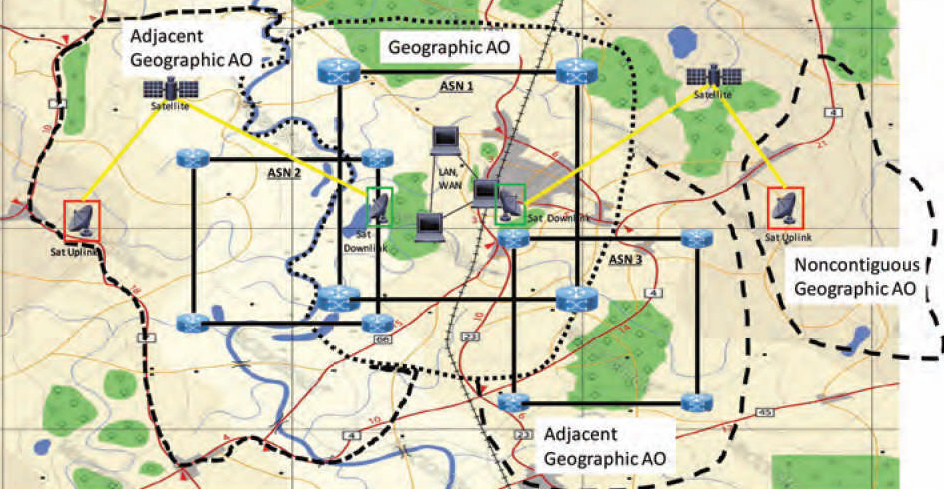

With a concrete understanding of the construct of relevant networks in a geographic AO, it is imperative to consider outlier technologies, which may bypass the ASN structure. Users within a geographic AO may leverage satellite communications (SATCOM) for data transferal.9 For this reason, the C-AO should include all satellite coverage areas that fall within the geographic AO, the associated, command link data systems, and all of the relevant downlinks. In addition to SATCOM, cellular networks should be included in the C-AO. Cellular networks generally fit more neatly into the geographic AO because of their reliance on the relatively short span of coverage provided by cell towers, which are largely concentrated in developed areas.10 (See Map 3.)

The combination of ASNs, subordinate networks, SATCOM infrastructure, and other cyberspace entities relevant to a specific geographic AO should make up the related C-AO. These entities are logically represented by IP addresses, media access control addresses, and other cyberspace selectors. FSCMs are the method by which the C-AO may be deconflicted.

Traditional FSCMs are either permissive, which facilitate attacks and minimize coordination, or restrictive, which are imposed to safeguard friendly forces. While traditional FSCMs are depicted as specific graphics on maps, FSCMs in cyberspace may not fit as neatly. Instead, they may be better represented as lists of IP addresses, media access control addresses, or other logical designators that appear in the relevant cyberspace. These lists should include details regarding restrictions, rules of engagement, and coordination instructions. For example, a cyber no-strike list is a restrictive FSCM composed of a list of targets within a designated C-AO upon which cyber effects are not authorized. A cyber-restricted target list, on the other hand, is a list of cyberspace targets within a designated C-AO which require additional coordination prior to firing because either another coalition entity is planning a similar operation or the target is politically sensitive and would require interagency approval. Known cyberspace elements that do not appear on either of these lists would be placed on a cyberspace joint target list and require no additional coordination prior to firing. These cyberspace FSCMs are akin to those used in the physical realm to aid commanders in the targeting process.

Delineating the cyber battlespace and implementing associated FSCMs would enable a commander to quickly assess which cyber targets are relevant to his AO. Further, it would allow him to understand the coordination requirements to attack a cyber target, which would enable tempo in cyberspace and could facilitate a commander’s attack on cyber targets to out-tempo his adversary. However, it is important to note that cyberspace rapidly changes. Since cyberspace is constantly updating, the joint force must construct a realtime monitoring authority to facilitate deconfliction. This will be resource- and time-intensive but is the only way to facilitate the rapid engagement of targets needed to outmaneuver an adversary in cyberspace while ensuring the prevention of fratricide.

“But Cyberspace is Different”: An Erroneous Premise

Despite the growing acceptance of cyberspace operations as commonplace, a widely held belief regarding cyberspace operations is that they are too complicated to be compared to traditional military operations. Authors have warned that cyberspace is filled with attackers capable of appearing and disappearing at will, stealing identities, and shifting network nodes.11 While all this is true, if one breaks down cyberspace into separate AOs and implements an authorization authority, his perspective may be more optimistic.

Further, others have argued that the cyber battlespace is composed of only a singular battlefield. The argument is that since there is only “one Internet” which comprises the World Wide Web, then there may only be one cyber battlefield.12 While this argument warrants some merit, it is analogous to an exclamation that because there is only one Earth, there is but one physical battlefield. To mitigate ideas like this in other domains, the joint community divides battlespace in the air, land, and sea and assigns commanders responsibility for the various aspects of those domains which relate to their military mission. Additionally, the Marine Corps traditionally views all battlespace through the “single battle concept,” in which an action taken in one area of the battlespace may very well impact an action taken in another, potentially noncontiguous area of the battlespace. Marines have already accounted for the fact that there is a singular Earth and that military operations are rarely linear and confined to any singular space therein.

Cyberspace is indeed “different,” but only inasmuch as airpower was different to warfare during the attritionist fight in the pre-World War I world. Though both sides of the war exuded initial skepticism, the advancement of air power and the control thereof became a prominent factor in overall strategy by the conflicts conclusion.13 After World War I, the air domain became commonplace to war as we know it. Cyberspace will follow suit.

Conclusion

The ability to out-tempo an adversary is key to winning at maneuver warfare. Tempo demands that a commander must have decentralized control of his operations. To facilitate tempo, the joint community establishes boundaries and control measures in the air, sea, and land domains. Despite the differences that exist in the cyber domain, boundaries and FSCMs in cyberspace will enable tempo in the cyber domain.

Notes

1. Headquarters Marine Corps, MCDP 1, Warfighting, (Washington, DC: 1997).

2. Col John R. Boyd, USAF, Patterns of Conflict, (Online: December 1986), available at www. dnipogo.org.

3. James Lacey, “A Historical Look at the Future,” lecture given at Expeditionary Warfare School, 21 August 2017.

4. MCDP 1, Warfighting.

5. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Operations, (Washington, DC, 2011).

6. Ibid.

7. Geoff Huston, “Exploring Autonomous System Numbers,” The Internet Protocol Journal, (Online: 29 July 2015), available at http://www. cisco.com.

8. Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Operations.

9. “Satellite Basics,” Intelsat General Corporation, available at http://www.intelsatgeneral.com.

10. Michael Miller, “How- Mobile Networks Work,” in Wireless Networking: Absolute Beginner’s Guide, (Online: 14 March 2013), available at http://www.informit.com.

11. MAJ Matthew Miller, LTC Jon Brickey, and COL Gregory Conti, “Why Your Intuition about Cyber Warfare Is Probably Wrong,” Small Wars Journal, (Online: 29 November 2012), available at smallwarsjournal.com.

12. Kenneth Geers, “Cyberspace as Battlespace,” Black Hat, (Online: 9 October 2014), available at http://www.blackhat.com.

13. Bernard Wilkin, “Aerial Warfare during World War One,” British Library, (Online: 29 January 2014,) available at https ://www.bl.uk.