Turning Advocacy into Action

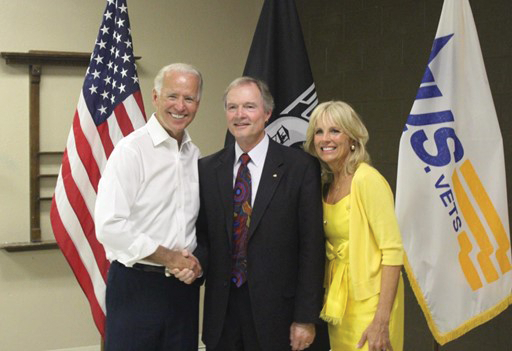

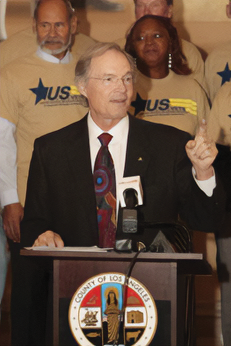

Posted on December 15, 2022Featured image: Stephen Peck, CEO of U.S.VETS, at the opening of Veterans One-Stop Service Centers at Patriotic Hall in Los Angeles, Calif., 2014.

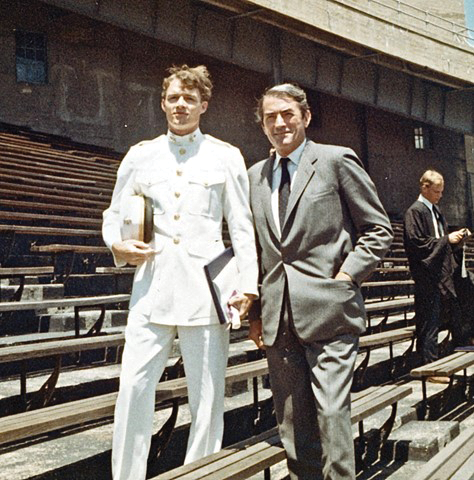

Stephen J. Peck is the president and CEO of the United States Veterans Initiative (U.S.VETS), which is the nation’s largest nonprofit devoted to providing housing and other essential services to at-risk veterans. He is descended from a Hollywood legend; his father is the late Gregory Peck, but Stephen chose a different path for his career. Peck served in the Marine Corps and was an artillery officer in Vietnam.

U.S.VETS opened its first facility in Los Angeles, Calif., in 1993 and has grown to 11 sites in five states including the District of Columbia. The nonprofit serves more than 5,000 veterans a day and helps 8,000 veterans find housing and more than 1,500 veterans gain full-time employment annually.

Peck lives by a lesson learned in the Corps: “If you don’t go where the trouble is, you can’t solve the problem.” He shares his Marine story, continued service, and current activities in his interview with Leatherneck.

What are the greatest life lessons you took from your service in the Corps?

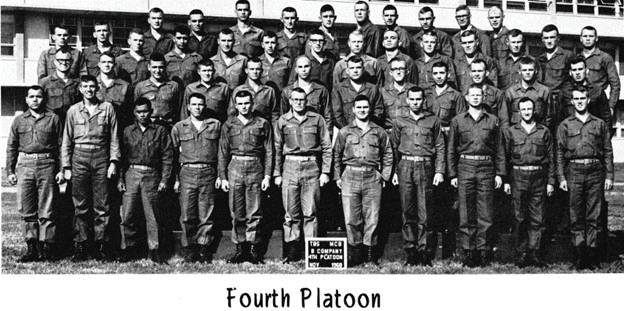

I was drafted after my sophomore year and got my 2S deferment then joined the PLC [Platoon Leaders Course]. I did not want to be a private in the Army. I wanted to be surrounded by trained killers, and the Marines were the way to go.

I’ve been around several military events recently and am so impressed with young Marines these days. They are professional. They are disciplined. They are respectful … The fact that we all have been through TBS (The Basic School) from the Commandant on down, we’ve all had that same training and it’s important to bring us all together. All of us carry that [bonding moment] who have been Marines. We all have experienced that and use it. I use it regularly and try to build that esprit de corps in the agency that I run. I use those leadership principles. You put your ego out of the way so that they can do the best job that they can. That comes right from the Marine Corps.

I run a big organization and we have 500 employees. That’s not something I can possibly, even remotely, attempt to do by myself. I must have key people underneath me and I must make sure they’re supported. The term “I’ve got your back” is totally overused these days, but in Vietnam, it was a real thing. It was serious. I knew that they [the Marines] did, and they knew that I did. That’s essential in combat. The people that work for you must know that you’ve got them. I’m going to send you out there and you’re going to do this. Whether you succeed or fail, I’ve got you. And if you fail, we’re going to try again and we’re going to try again.

It’s all about accomplishing the mission, no matter who does it. We’re all doing this together. It’s really critical. We try to teach that to all our site directors and managers. Some people get into a leadership position and it’s all about me; I have to do this and make every single decision and every decision has to come through me. They don’t understand that you really have a whole team of people under you, and the more knowledgeable and more professional and more committed they are, the better you are [going to] look at the end of the day, but it’s not about you. It’s about accomplishing the mission and getting homeless veterans off the street. I’m happy to give credit away, it doesn’t matter. Our results are what matters.

What’s important is how many men and women we get off the streets and how many we get into housing and how many we get jobs. That’s what we’re all about, not about any one of us. I’m getting on in years and probably have a couple of years left of doing this. This has to continue on. I’m the only leader that has been here since the beginning of this organization, 29 years ago this month we brought five veterans into a facility in Inglewood. Now we’ve got 600 formerly homeless veterans in there. We house another 2,400 more in 11 metropolitan areas across the country. If I disappear it’s [got to] go right.

Fortunately, I’ve got a Marine as my second [in command], so I’m good to go. He’s been with us for 19 years. Our CFO is a Marine. We’re rotten with Marines here. We learned in the Marine Corps that you have to accomplish the task whatever that is. Over, around, under, or through. You’ve got to accomplish the task. If you don’t accomplish it the first time, you have to keep going. Use your imagination. Use other people. Whatever you’ve got to move forward. We learned that in the Marine Corps and in combat you don’t have a choice. You have to protect your team. That is life and death. It is life and death for some of the homeless veterans we encounter. We have to stick with it. Whatever our particular task is, we’ve got to get it done. If you get a “no,” try to bring in someone else. Maybe you’re not the right person to get that task done. Let’s pass it off to this person or maybe somebody else knows someone who can get it done. It’s all about getting the job done. It’s about getting veterans off the streets.

I was assigned to the artillery so after TBS I went down to Fort Sill and became an artillery officer. I was assigned as a Forward Observer with “India” Company, 3/7. I was about 15 miles west of Da Nang at Hill 10. Those memories don’t leave you. I was going on patrols for the first three or four months—mostly platoon sized patrols immediately west of Hill 10. We were the last emplacement out there. Hill 10 wasn’t very big. It was what they called “Indian Country”; you don’t go outside the wire because you don’t know what’s out there. We went out in units, and we’d be out for two weeks. We’d come back in for four days and then go back out for two weeks in the mountains where the NVA was operating. Our task was to be a presence to prevent them from rolling down that valley going east into Da Nang. We were part of Operation Oklahoma Hills going out as a company and there were other companies going up into the hills there. We were there to intercede the activities of the NVA (North Vietnamese Army) and Viet Cong up there.

Even at the bases we regularly received mortar fire and rocket fire. I was rocketed on my birthday, Aug. 16, 1969. I was at Hill 55 at that point which was the 7th Marines headquarters. It was a big base; it’s a pretty safe place and our company commander was talking with battalion about where we were going to go next. We were chilling out for four days and I was in the officers’ club, which is essentially a big hooch. There was music in there and there was a bar in there, so it was semi-normal.

Rockets started falling outside and a whole bunch of us ran out the door into slit trenches. We ran about 50 feet and piled into a trench, one on top of the other. We were piled three or four high. Rounds were dropping as we were running. Miraculously, no one got killed.

I feel lucky all the time, any number of times it could have gone differently. One tour of Vietnam was enough for me but it’s extraordinary how exhilarating combat is, you’re wired. You’re buzzed. The last few months in country I was at Division headquarters in S-2. A lot of times they put officers in the rear for the last few months. I had like an eight-hour job. I was in the S-2 office for an eight-hour shift and then kind of hung around. I remember thinking one night, combat was a lot more exciting than this. I had to tell myself not to volunteer to go back out there. You got out of that situation once, don’t take another chance. It’s terrifying, but it’s thrilling. Boy, do you have a mission—to stay alive and accomplish the task. A lot of guys come back from combat, and they miss that. Their life seems kind of empty.

I remember feeling kind of rootless when I came back. You’re just not in a life and death situation at home unless you are a cop or something. You miss that adrenaline. It’s a real problem with some guys. Some guys volunteer to go back and I know a couple guys that did. A couple guys didn’t make it back after that second tour. It’s a real emotional dilemma that you face when you come back.

Can you share some of the statistics of success with your organization?

We came along about the time when the homeless veteran movement was really gaining steam. There was a group of guys who started the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans. That was really the beginning of the homeless veteran service movement. Now there are some 300 organizations across the country bringing homeless veterans into housing and off the streets. When we started in 1993 there were about 240,000 homeless veterans in the United States. Today there are a little less than 40,000 so we really are accomplishing the mission here. Now we’re dealing with more challenging groups. We got all the low-hanging fruit. The guys who we bring in, get them a job and push them back out into the community. We got those guys. But there are a lot of veterans that are suffering from some sort of mental illness, substance abuse issues, real emotional problems, tragedy in their life, PTSD, TBI, you name it. They just can’t set one foot in front of the other because they are so preoccupied with their combat experience. That’s a more challenging group.

We have about 1,000 rehabilitation beds with intensive case management. Let’s find out what got them homeless in the first place. Let’s get them back to work if they are able to work. Let’s get them into permanent housing so they are not on the street anymore. We are also emphasizing two other parts of it which are homeless prevention and mental health services before they become homeless. So, we are expanding those programs and on the other end, building more permanent supportive housing.

We’ve got about 2,400 permanent housing beds at the moment and are building another 450 or so as we speak. There’s a lot more funding available and we’re one of those agencies that are doing everything we can to solve that drastic shortage of affordable housing with the support services that will keep these men and women stable. We run all types of therapeutic groups at our sites whether it’s AA [Alcoholics Anonymous], PTSD groups, fatherhood groups, financial literacy, the whole nine yards. We want them to be independent when they leave us. That is the whole goal. Create an independent guy who can be a contributor to the community.

What inspired you to join and lead U.S.VETS?

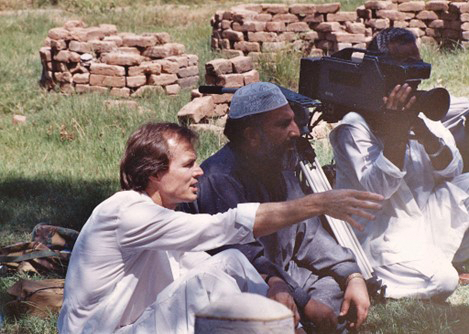

I was a documentary filmmaker and had a particular interest in homelessness. I had done a couple of films about homelessness in the Tenderloin in San Francisco. In the late 1980s, someone told me that one-third of homeless men were veterans. I did a short film on my own down on Venice Beach in Los Angeles. Someone pointed out to me that there was a group of veterans living on the beach down there, so I went down there with a film crew and filmed them. Six Vietnam vets, totally disillusioned, angry. These were some of the guys who came back and were not welcomed home. They were made to be ashamed of their service and it really embittered them. They were just saying to society, “To hell with you, I’m out here on the beach, just leave me alone.”

I did a short film and started using that for advocacy. My idea was to do a one-hour film on homeless veterans. But one thing led to another, and I became an advocate with the West LA VA [Veterans Affairs]. I didn’t want to leave that advocacy behind because I was so into it. The VA ultimately offered me a job in their outreach department and as a liaison to the community. I started as an outreach worker in 1993. Going out under the bridges and into the shelters bringing homeless veterans in off the street. I learned from the ground up what homeless veterans needed, what their desires were, what their challenges were, and that education was invaluable. I spent a few years really learning what we needed to be doing so we could create programs to help them.

I was with the VA until 1996 then I jumped over to U.S.VETS. I wanted to be able to do more … they had just started. I was an outreach worker assigned to this brand-new nonprofit in Los Angeles and brought the first five guys in. Then we had 25, then 100. Now that’s the site that has 600 vets. We learned by making all the mistakes. We learned what it was that veterans needed. Not only the housing but the services, the support services, the clinical counseling and employment services. They need those three things [housing, support and employment] together. They didn’t just lose their home. Something happened, maybe losing a job, losing their family, losing their income to the point they can’t pay rent and then they’re out on the street. We have to address all those issues.

“Heart of a Warrior” is the documentary that led me to change careers. We filmed in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Russia, Vietnam and the U.S. It showed in festivals all over the U.S., VA Medical Centers, Walter Reed Army Hospital to a group of 60 psychiatrists as the Gulf War was heating up, and Harvard School of Government. Bob Sampson and I attended many of these screenings together to participate in panels. Here’s the short description:

“Bob Sampson is a former U.S. Army paratrooper who fought in Vietnam until his left leg was shot off. Nikolai Chuvanov is a former paratrooper in the Soviet army who served in Afghanistan until his right leg was shattered by a bullet. “Heart of a Warrior” movingly portrays the personal aftermath of war for these two men. Both still suffer from the emotional damage, unresolved moral questions and enduring pain of wartime. Through compassion, camaraderie and even humor, these former warriors form a powerful, healing bond and offer a message of hope.”

We’re now at a point where we are about to reduce the number of rehabilitation beds we need in Washington, D.C., because we’ve knocked the homeless population down. The street population of veterans in D.C. last I heard a week ago is 27. Nationwide we’ve got about 1,000 of the grant and per diem beds from the VA. We’re paid per veteran that you serve on a monthly basis. You’re expected to provide housing, meals and all of those services that are going to make them whole again. Those are really important beds to us. We’ve got 85 of those beds in Washington, D.C. But now we don’t need 85 anymore. We’re going to reduce it to whatever the need is … then transform the other space into permanent supportive housing.

We hope this process happens all across the country. We knock the numbers down so low that we have to redesign our programs to fit this new reality, creating more permanent housing on the one hand and creating homeless prevention programs on the other so we prevent veterans from becoming homeless. It is strategic and has an immense financial impact.

You’ve got to face these problems head-on. In the Marine Corps, you learn to face enemy fire, you don’t turn your back on it. Homelessness is one of those issues that people are kind of afraid of, it’s such a big societal issue. Most people don’t know what to do about it. Do you give them money or give them a bus ticket? We have to look at it right in the face. We happen to be one of those agencies that have the capacity to do that and feel a real responsibility for that.

What new programs and initiatives are you working on for veterans?

A lot of focus has been on veteran suicide and it’s not getting any better. It’s happening among veterans and in the military. Twenty veterans and military a day are taking their own lives. We have to address that in some way, a more significant way than we have been. We started our homelessness prevention program in Los Angeles and all that mental health programming that we do is ultimately about suicide.

We’ve started a Women’s Veteran on Point program that’s a portal that reaches out to women that are not seeking services. Only a third of women veterans are seeking services at the VA. They view it as a male bastion. This is particularly true when a woman veteran walks into the waiting room at the VA and she has experienced military sexual trauma and there are 20 guys in there, she’s not comfortable in there. She’s going to walk right back out. So, we initiated this portal where there is a chat room, there is a self-assessment tool and then a phone number to call. You can come in and get counseling either in person or through telehealth.

What COVID has done is really expanded our ability to provide telehealth and we want to spread that throughout our programs across the nation so that we are serving not only the veterans within our walls but also into the wider community.

The highest number of homeless veterans in the country is in Los Angeles. In Los Angeles, the West LA VA over the last decade has been receiving lots of criticism because it hasn’t been housing homeless veterans. Many of the buildings for housing veterans there have been abandoned for decades.

The VA put out a request for proposals a few years ago and U.S.VETS along with two other partners were chosen as the principal developers to develop up to 1600 units of permanent supportive housing on that north campus. We’re well into it at this point. The first building will open this fall in November or December. That will be for 60 senior veterans, who are one of the fastest growing homeless populations in the US. We have another 400 units coming online by 2024 and are continuing to raise money to build up to 1,600 units. We will also build support service space for homeless prevention programs.

We will not only house 1,600 veterans, which is nearly half the number of the homeless vets on the streets of Los Angeles, but if we can prevent more vets from becoming homeless, we might be able to significantly solve the problem here in Los Angeles. It is a monster project that will take eight to 10 years to accomplish. The VA has stepped up during the pandemic and placed about 120 tiny shelters on the grounds to get veterans on to the campus and out of tents and now they are challenged to provide the level of service those veterans need. The VA has also stepped up and is helping us redo the infrastructure. All the water, power and telecom. They have put up a bunch of money to build the backbone of the water and sewer to the different buildings. We’re out there raising money to build the buildings and to provide the support services. We’re going to create a real close-knit community with resident councils and town halls so the veterans will have a lot to do and to say about what goes on there so that we are providing the best support for them.

What are you most proud of from your service?

I never imagined that when I got out of the Marine Corps that I would be doing what I’m doing. There was no thought in my mind that I would have anything to do with the military again. The Vietnam experience was enough for me. I was done. But those thoughts and emotions don’t leave you. Ultimately it led me back to what I’m doing where I have an outlet for all of that. That’s the legacy that the Marines have left me with. They got me into a career that has been extremely rewarding.

Author’s bio: Joel Searls is a creative and business professional in the entertainment industry. He writes for We are the Mighty. He serves in the Marine Corps Reserve and enjoys time with his family and friends.