The Illustrated Marine

By: Kyle WattsPosted on December 15, 2022

A dichotomy of perception resounds today, as true as it has for decades. One group has always viewed tattooed Marines as a stigma, a mark of the undisciplined or unprofessional. The opposing sect, perhaps inspired by the first, revered the Marine who was covered in ink. Many USMC veterans can look back at their time in the Corps and instantly remember their drill instructor or gunny or some other grizzled old warrior covered in tattoos, smoking a cigarette, and spitting dip into an empty beer bottle. In school circles, these Marines punctuated their wisdom with every profanity known to man, all the while teaching us something we would never forget about being a Marine. They were terrifying, inspiring, and made us strive to be the best we could possibly be.

Conflicting opinions on tattoos impacted many Marine careers over the last few decades. In spite of this, Marines and their tattoos continue telling stories. Policies or perception have deterred few who wanted a tattoo. Quite the contrary, Marines seem even more proud of their ink.

Adam Krick is one of these proudly tattooed Marines. He returned home from his first deployment to Iraq in February 2005. He and the other veterans of 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines enjoyed the bonds they formed in combat. Krick knew the experience would stick with him forever, and he wanted to memorialize it. He walked into a tattoo parlor outside the gates of Camp Lejeune and considered his options. A lot of guys went with the eagle, globe and anchor. Krick liked that idea, but instead selected a less traditional “tat.”

In Iraq, Krick had humped around a medium machine gun. He loved it, and he loved the camaraderie he shared with his fellow 0331s. As he sat down in the tattoo parlor, Krick presented a photograph of an M240G straight from the machine gunner’s training manual. He told the artist to draw the gun on his forearm as large as possible. The end result, stretching from wrist to elbow, left Krick looking unique among his peers.

“After that, I figured I couldn’t just do one because machine guns are always deployed in pairs,” Krick recalled. “I went back and got another 240 on the other arm to match.”

On leave at his home in Pennsylvania, Krick followed up his pair of tattoos with a traditional eagle, globe and anchor on his bicep. He returned to Camp Lejeune full of pride.

“Back then, obnoxious moto tats about your MOS weren’t really a thing yet, so I got ridiculed pretty hard by my senior enlisted.”

Krick joined his company in formation one day when the company gunnery sergeant called him to the front. The gunny made Krick raise his arms above his head, putting his 240s on display. After berating Krick in front of his peers, the gunny forced him to demonstrate “talking guns” with his inked weapons. He struggled to contain his laughter as he alternated arms boxing the air, making machine gun sounds with each punch.

The experience served only to make Krick prouder of his tattoos, and he continued adding ink to his collection. At the same time, the Marine Corps revised its policy on tattoos. In 2007, while back in Iraq on his second deployment, Krick learned that tattoos on the forearm were no longer allowed. In order to avoid disciplinary action, his 240s needed to be photographed, added to his Service Record Book, and “grandfathered” into the new policy. While still in country, manning a remote traffic control point in Rutbah, Iraq, a senior Marine photographed Krick’s tattoos on a company camera.

Multiple times before Krick’s experience in 2007, and numerous times since, the Marine Corps changed its stance on “acceptable” tattoos. Ink on skin has always carried some association with an unprofessional appearance.

“It appears that the newer generation [of Marines] has taken to eccentric appearances of the popular culture,” stated one Marine officer amid a major tattoo policy change. “The new policy sends a message to all Marines that this type of behavior does not fit into the conservative image the Marine Corps wants to project.”

Although this quote might easily be confused with sentiments from present day, the officer made these comments more than 25 years ago in May 1996. It is also curious that the policy implemented back then proved more lenient than today’s policy, prohibiting tattoos on the neck and head only.

Regulations have come full circle over the last two decades. In 2007, the Corps instituted additional restrictions, outlawing sleeve tattoos. Marines like Adam Krick were grandfathered into this new policy, but still faced potential roadblocks to their career development. These restrictions were spelled out in 2010 through an official policy “amplification.” Any enlisted Marine with sleeve tattoos, even those grandfathered, became ineligible for officer and warrant officer commissioning programs. Additionally, these Marines, regardless of service record or fitness reports, were barred from billets such as recruiting, drill instructor, and Marine security guard.

The changes met backlash. Some could not reconcile the Corps’ desire to preserve a traditional appearance with the impact these decisions had on many within the ranks. One 2007 opinion piece in Marine Corps Gazette presented the opposition argument crystal clear.

“The amount of ink a Marine sports isn’t indicative of maturity level; behavior is… To me, there is no uniformity in a nontattooed, poorly behaved Marine dragging his peers to his bottom-feeding level. I’d prefer the illustrated man who is motivated, dedicated, and educated to lead America’s finest fighting force.”

A more forceful opinion article appeared in the Marine Corps Gazette in 2015.

“The current tattoo policy is a blanket doctrine that is often misused to prevent the professional advancement of a warrior … How is this strengthening the fabric of our Corps? Often, these exemplary Marines become so disgruntled that they choose instead to exit active service and leave the occupational field, depriving the Corps of leadership and experience, all because the Marine is not afforded the chance to progress based on a few tattoos.”

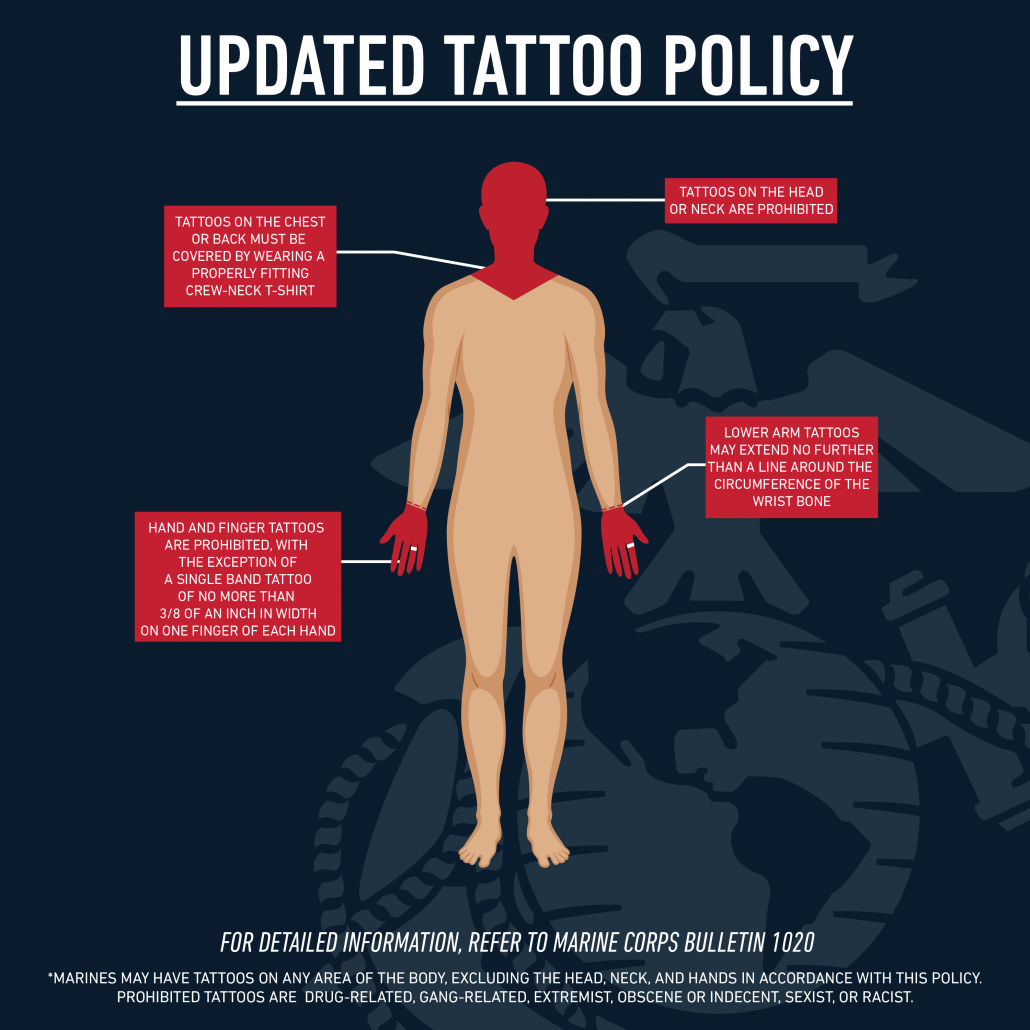

The Corps’ leadership began changing regulations in 2016 with Marine Corps Bulletin 1020. More tattoos were approved for more body parts but determining if your ink fit the criteria proved arduous. The 32-page document covered every inch of skin, detailing the new directive in excess. Photographs, body diagrams, and measuring instructions specific to each body part filled the pages. The bulletin even contained official USMC printable tattoo measuring tools. Marines were supposed to print the device themselves, cut it out, and utilize it over their knees and elbows. No detail remained unspecified, lest any computer illiterate Marines venture into the agonizing task. A full page outlined formatting and printing instructions, complete with diagrams, screenshots, and color photographs demonstrating how to cut along the dotted lines. Perhaps a Marine deciphering his career prospects through a free printable held against his body would have found it more humorous if the photos at least featured crayons.

Robert Ham enlisted under these policies, but routinely entered unfazed into tattoo parlors stateside, in Hawaii, and in Korea. He served as a machine gunner with 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines from 2014 to 2018. He walked away with multiple tattoos commemorating parts of his time on active duty.

“My whole platoon got a pineapple grenade as an ode to the Hawaii Marine Corps,” Ham recalled. “Setting your own headspace and timing was becoming a lost art, so all the machine gunners got a headspace and timing gauge. A bunch of us got a pirate flag at infantry school. Fresh out of boot camp, I got my typical moto tat, ‘Semper Fidelis’ on my ribs.”

Ham collected more tattoos, each one drawing up a memory and story from his time in the infantry. He started a sleeve on his left forearm while on active duty, but due to the tattoo policy at the time, waited until he left the Marines in 2018 to finish it. Now a professional firefighter in Virginia, Ham continues inking his body with tributes to his new squad, his wife and his children.

“I think a lot of people love the idea of the Marine Corps and what it stands for, but once you’re in, it can be a little frustrating. A lot of guys talk negatively about their time in the Marine Corps, but still come away with tattoos. That’s because of the bonds you make, sitting on field ops for days on end with all the wild and crazy conversations, just being with your boys.”

Current tattoo guidance evolved in October 2021. An official review determined the old regulations, “were believed to have an adverse effect on retention and recruiting efforts.” The new message came refreshingly clear and simple; “Marines may have tattoos on any area of the body, excluding the head, neck, and hands in accordance with this Bulletin.”

Exceptions and potential career implications still exist. The content of a Marine’s tattoos will be scrutinized more thoroughly. Even so, in general, if a Marine today wants ink, he or she can get it.

Every policy change across time spawned from the same motive; the Corps has a responsibility to maintain a disciplined and professional appearance. In his updated bulletin of last year, however, the Commandant expressed a judicious observation.

“This Bulletin ensures that the Marine Corps maintains its ties to the society it represents.”

What is the definition of a disciplined and professional appearance? It appears the Marine Corps has remained firmly committed to this philosophy. The society it serves must have changed. A traditional appearance might no longer be equated to a professional appearance. A person’s level of discipline might no longer be measured, in part, by the amount of ink on their skin.

Regardless of shifts in policy or society, Marines continue getting tattoos. They desire to display their individual experiences; the things for which they are most proud or most impacted. Vinyl stickers splashed across a vehicle or bedazzling a Yeti water bottle can only go so far. What can be more powerful than inking your own canvas of skin?

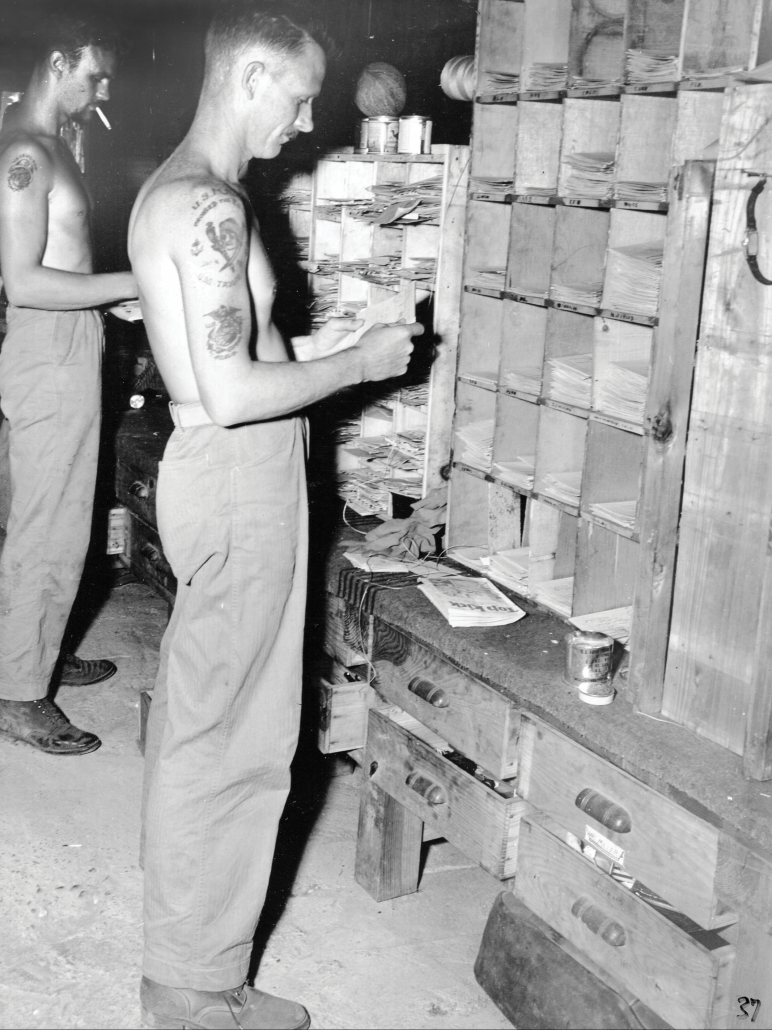

Though tattoos may be greater in number and variety, their significance to Marines remains unchanged. Captain Robert Asprey, a World War I veteran of Belleau Wood, affectionately remembered his drill instructors as, “the tall, straight, mustached professionals who dressed their pride in gaudy blue uniforms, decorated their bodies with salty tattoos, fed their thirst with chewing tobacco, frequently dipped snuff, assuaged fatigue with whiskey, cursed with the metric vigor of Kipling … and knew everything there was to know about the Springfield .03 rifle.”

Some of the most famous Marines to wear the uniform proudly bore their ink.

“I selected an enormous Marine Corps emblem to be tattooed across my chest,” stated Smedley Butler, two-time Medal of Honor recipient and legendary Marine general. “It required several sittings, and hurt like the devil, but the finished product was worth the pain. I blazed triumphantly forth, a Marine from throat to waist. The emblem is still with me. Nothing on earth but skinning will remove it.”

Another Medal of Honor recipient, John Basilone, inspired generations of Marines with his tattoos. He sported a cowgirl pinup on one bicep. The other arm bore a popular military tattoo, a dagger plunged through a heart and wrapped with a banner proclaiming the ubiquitous, “Death Before Dishonor.”

Thousands and thousands of Marines across time inked their bodies with a standard, “moto tat.” An eagle, globe and anchor, or bulldog head were common. These timeless drawings remain popular today. Many Marines, however, prefer a more unique tattoo.

David Meza, a former Marine Corps Security Forces Guard and 0311, received his moto tat while home on leave in 2017.

“My uncle, who is a Marine as well, took me out to a bar and asked, ‘So what’s going to be your Marine Corps tattoo? You know, the one everybody gets after graduating boot camp.’ I told him I didn’t want something typical, so I found this image scrolling through social media and he was like, ‘Let’s go get it right now.’”

The finished product, “Protek the Crayonz,” received a laugh from everyone at the unit.

Another Marine veteran, David Tyma, took a more satirical approach to his moto tat. Tyma served as an Amphibious Assault Vehicle crewman and repairer at Camp Pendleton.

“We always joked about how we keep the Marine Corps amphibious, and I basically spent four years just sitting on the beach at Del Mar. I don’t remember if I came up with the idea for the tattoo or one of the other guys did, but we talked about it enough that I finally decided to do it.”

Tyma altered the traditional eagle, globe and anchor into a seagull, beach ball, and umbrella. Now off active duty and serving as a professional firefighter in Nebraska, Tyma routinely runs into other veterans who recognize his tattoo.

“I get a lot of crap over it, especially from older Marines. They think it’s trash or an abomination, but to me, it’s a joke and it sums up my Marine Corps experience perfectly.”

Perhaps Garrett McMahon, a 0311 from 2015 to 2021, wears the most motivated of moto tats. In fact, his evolved into an entire sleeve dedicated to USMC warriors throughout history. The WW I-era painting of a Marine bayonetting a German soldier covers an entire side of his forearm. The silhouetted Marine photographed while sprinting under fire on Okinawa honors Marines of WW II. McMahon paid homage to Korean War veterans by adding the 1st Marine Division’s patch from that era. Another famous Vietnam-era photo of Carlos Hathcock peering through the scope of his sniper rifle covers the outside of his arm. A modern battlefield cross honors veterans of the Persian Gulf, Iraq and Afghanistan. As a final personal touch, McMahon included his grandfather’s dog tags on his wrist. His grandfather fought in two wars as a Marine, surviving landmark battles such as Guadalcanal and Bougainville in WW II, and the landing at Inchon in Korea.

As sacred as their moto tats, many Marines proudly wear ink they received unintentionally. Alcohol, a lost bet, or some combination of both, typically serve as the catalyst. No matter what these tattoos turn out to be, they forever represent a piece of the brotherhood the individual shared during his time in the Corps.

“One night, after a bottle of Jack Daniels and playing Mortal Kombat in the barracks, I made a bet with one of my fellow boots that I could beat him in a game,” remembered one hard charger. “The loser would get the winner’s name tattooed on their butt, with another tattoo of the winner’s choosing. I lost, obviously.”

After months of putting it off, and incessant taunting from his buddy, the Devil Dog finally went through with the bet one week before shipping out to Twentynine Palms for Integrated Training Exercise (ITX). Beneath his trousers, the Marine sported a cute, baby unicorn on his left cheek, with his buddy’s name in a semi-circle over the creature’s rainbow mane.

“The first night we were in Camp Wilson, I stayed up past midnight thinking the showers would be clear and nobody would see my fresh ink. After five minutes in the shower by myself, none other than my CO walked into the same shower as me. I could hear him laughing shortly after he came in. That made my first ITX very interesting.”

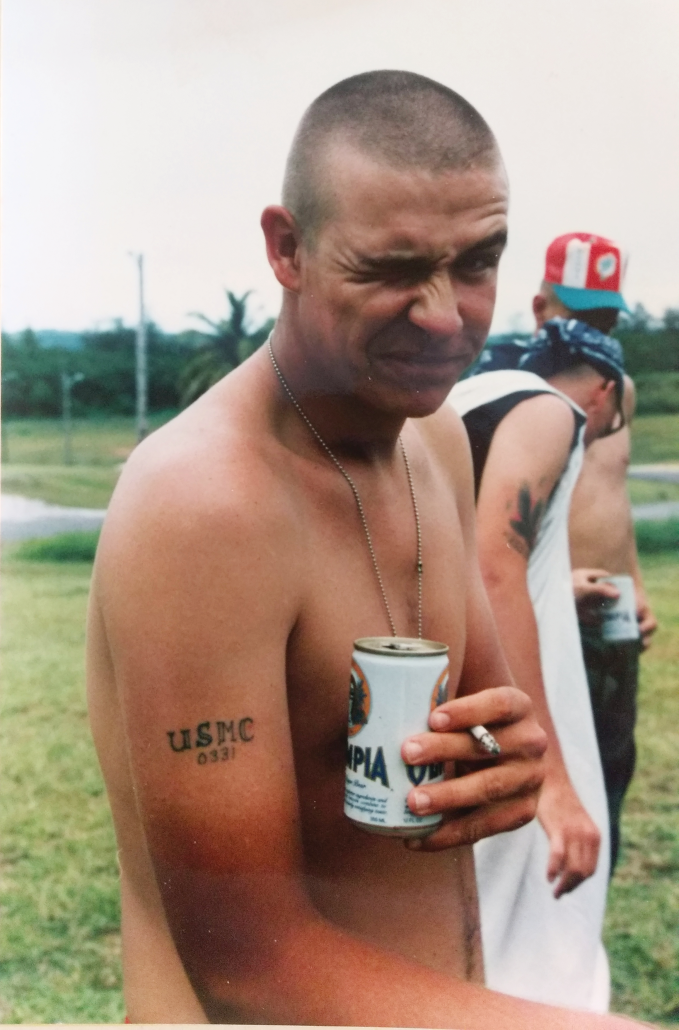

A sizeable portion of Marines allowed themselves to be inked by a buddy who was an aspiring artist. These “barracks tattoos” may not look as professional but are just as prevalent. Eric Althen perfected his craft tattooing other Marines while in the barracks on Guam in 1985. Althen entered the Corps as an 0331 the year before. He arrived on Guam to his assignment providing security on the naval base.

“At the time, I had been doing a ton of drawing. I think that’s how I was recruited into being the tattoo guy,” remembered Althen. “A couple of my buddies got a bunch of tattoos and we talked about them all the time. One of the guys with us was this hard kid who grew up on the streets of Los Angeles. One day, he told me I should make a prison tattoo machine. I’d never heard of anything like that, so he drew it out for me.”

The leathernecks gathered raw materials for the homemade device and got to work. They cut the bristles off an old toothbrush and bent the top over, then extracted the motor from a cassette player and mounted it to the toothbrush. They stripped down a Bic pen and blew the ink out of the reservoir inside, leaving a thin, hollow plastic tube. Althen found a Marine in the barracks with a guitar and convinced him to donate a length of guitar string. He filed the string to a point and fed it through the ink tube, then attached it to the motor. When powered up, the motor fed the string rapidly back and forth. He picked up a voltage controller at the PX to adjust the motor speed, and a bottle of Indian ink from out in town. Before long, Althen was in business.

He outlined his art on a willing Marine’s skin with a ballpoint pen. They requested all kinds of tattoos. Althen employed his machine to ink everything from “USMC” in block letters across a Marine’s knuckles, to a massive snake wrapping around and all the way up someone’s arm. Once outlined, he dipped the guitar string in the Indian ink and went to work.

“The tattoo process involves a lot of ink and blood. You’re constantly wiping it off so you can see where you’re going. Today, a normal person would have a microfiber cloth or something like that. I remember I couldn’t even find an old t-shirt to use, but I had a pair of underwear I was willing to sacrifice. They were freshly laundered, at least.”

Althen’s list of customers multiplied after his guinea-pig-Marine’s tattoo healed and turned out better than expected. By the time his island tour ended, with his prison machine and fresh pair of underwear, Althen inked more than 20 Marines.

“Some of the stuff I did back then, I would imagine it has all been covered up today,” Althen mused. “I’ve got a lot of tattoos, but I never tattooed myself. I knew better. Why these guys put their trust in me is beyond me!”

Whether received in the barracks or a tattoo parlor, more and more Marines are now telling their stories through their skin. MOS-specific tats permeate the ranks for every job from rifleman to combat camera. Often, the most meaningful tattoos honor the memory of a fellow Marine lost in combat. The Corps’ most recent casualties at the Abbey Gate of Hamid Karzai International Airport are memorialized in ink.

Von Straight served with Weapons Platoon, “Bravo” Company, 1st Battalion, 8th Marines in Kabul during Operation Allies Refuge. The suicide bomb at Abbey Gate detonated behind him on Aug. 26, 2021. Later that night, he and several others learned their friend, Sgt Nicole Gee, was one of the 13 American servicemembers killed in the attack. When they left Afghanistan, Straight and his friends designed a tattoo to remember her. The outline of Afghanistan lies in the middle with “OAR” written in Arabic inside, and “21” outside. A ring of 13 stars surrounds the country and text, representing each American killed at Abbey Gate. The largest, outlined star at the top of the circle represents Gee.

Whatever their motivating experience may be, Marines who memorialized a piece of their Corps on their skin found great meaning in the process. In the end, it boiled down to pride in being part of something great, and more importantly, remembering the brothers and sisters with whom they shared that time of life.

Marines from every era have more fully realized what the Corps meant to them after they got out. The culture of being a Marine, the struggle to earn the title, and the camaraderie shared is difficult to explain to outsiders. For many Marines, their tattoos will continue telling these stories. For many more to come, their stories remain to be inked.