“The Gift”

By: Kyle WattsPosted on April 15, 2023

Revealing the Lasting Impact of Corporal Jason Dunham

In 2003, film producer and director David Kniess caught a red-eye flight from California, bound for the East Coast. A young Marine took the seat next to him. They struck up a conversation, and Kniess soon abandoned any thought of sleeping on the plane.

“He was just one of those people that you meet, and you immediately know there’s something special about them,” Kniess recalled in a recent interview. “Very courteous, charismatic; one of those people you meet, and you don’t want the conversation to end.”

The two stayed up talking through the night as the flight crossed the country. Kniess learned the young man’s name was Jason Dunham. He would soon be deploying to combat with “Kilo” Company, 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines. When the plane landed and they caught different connecting flights, Kniess shook Dunham’s hand and told him to take care of himself.

Several months later, in May 2004, Kniess received a call from a friend.

“Did you see The Wall Street Journal today?”

“No, why?”

“Remember that kid you told me about? Do you know what he did? Go get the paper.”

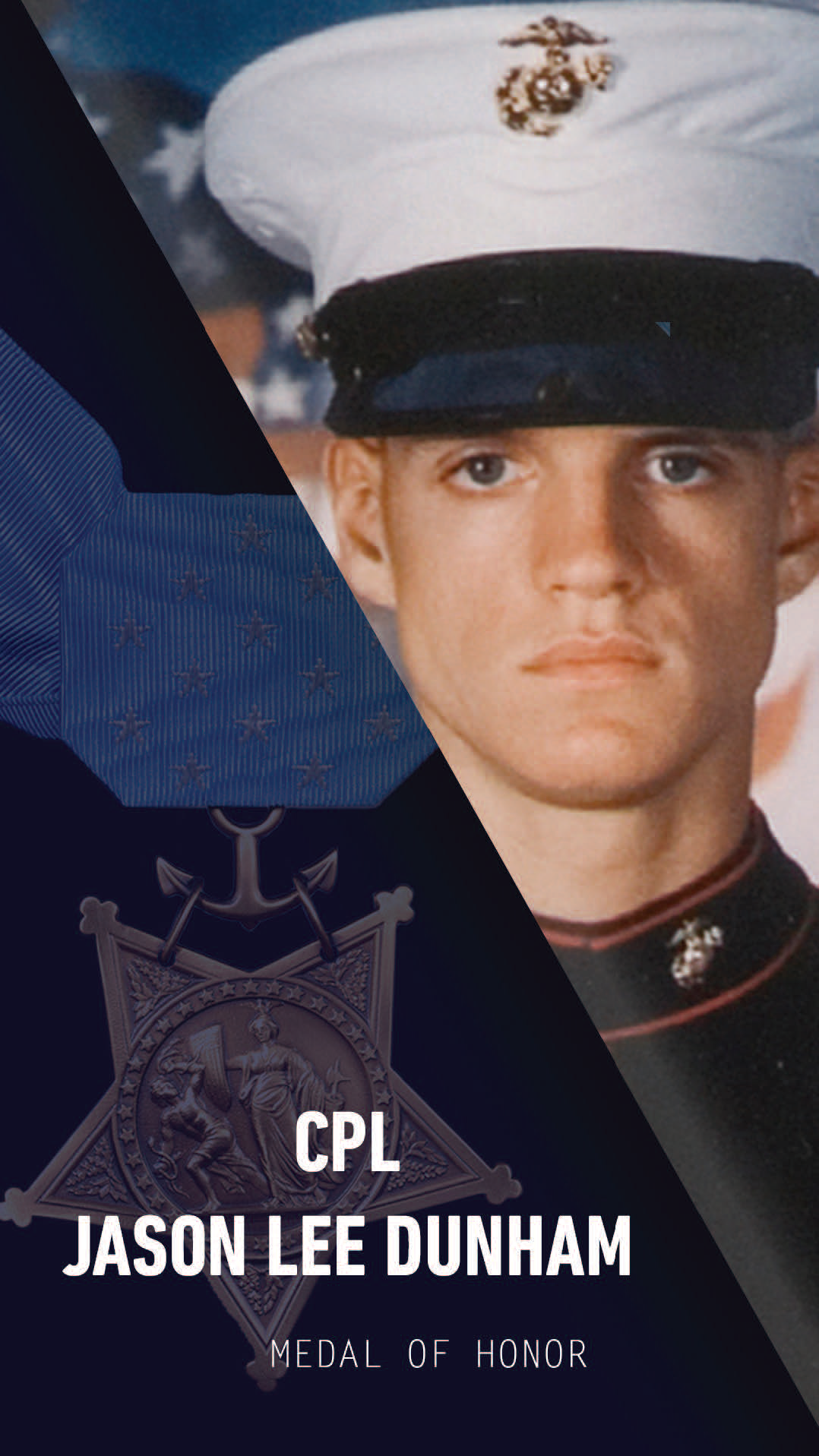

Kniess picked up a copy and saw Dunham’s portrait on the front page. He read on to learn how Dunham had been gravely wounded in Iraq and died eight days later after smothering a grenade with his Kevlar helmet to save the lives of two of his Marines.

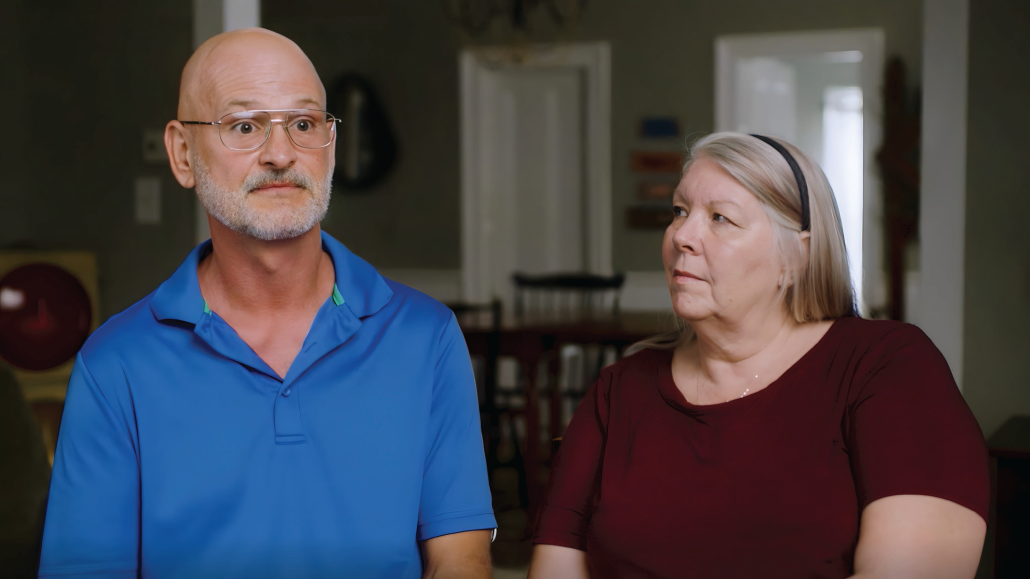

Kniess wrote a short story about his experience meeting Dunham on the flight and published it online. The story made its way to Jason’s parents, Deb and Dan Dunham, in Scio, N.Y. Before long, Kniess found a voicemail on his phone from Dunham’s mother. He initially ignored the message. What would he say to her?

When she called again, he realized he could not continue putting off the conversation. Kniess returned the Dunhams’ call, speaking with them about the story he wrote and reminiscing about their son. A friendship developed quickly, and within a month, Kniess was on his way to their home in western New York.

The relationship with the Dunham family expanded in the following months. In September 2004, Kniess met Dunham’s fellow Marines as they returned from their deployment in Iraq. He listened to their stories and learned the full details of what Dunham had done and became determined to create a documentary about Dunham and the Marines who served with him.

As the years passed, he maintained a close relationship with the Dunham family and the Marines Dunham served alongside. One by one they left the Marine Corps, while Kniess waited for the right time to tell Dunham’s story.

Shortly before Kniess met Dunham’s family and began developing relationships with his Marines, he had worked on a separate documentary covering Vietnam veterans in the battle of Khe Sanh. One of the Marines being interviewed, a Bronze Star with “V” recipient named Bob Arotta, struggled as he recounted the friends he’d lost.

“He told me some very graphic stories from his time during the siege,” Kniess remembered. “He told me, ‘You know, the things that happened then affect me more now than on the day they happened.’ That message was fresh in my mind as these guys started coming home from the war. I kept thinking, when is that day going to come for them? They were still in the Marine Corps. They still had the brotherhood. But I knew that day would come when the full effect of the war would hit them, and I worried about all of them. Sure enough, over the years I’ve seen the good, the bad, and the ugly. A lot of these guys are doing great now, but some of them aren’t with us anymore. It got to a point where they became old enough and a lot of this reflection had already happened.”

In 2020, 16 years after Dunham’s death, Kniess felt that enough time had passed, and it was time to tell the story. Not just the story of Dunham’s service and heroism, but also how his actions formed the foundation of life-altering events for so many others who served with him. Filming and production of the documentary began despite significant delays brought on by the Coronavirus pandemic. Travel and gatherings were restricted, but the team found a way to make it work as they traveled around the nation interviewing everyone necessary to tell the story.

LCpl Bill Hampton (left) and PFC Kelly Miller (right) fought alongside Dunham in Iraq and were wounded in the grenade blast that Dunham smothered with his Kevlar helmet. These Marines, along with numerous others from Kilo, 3/7, share the gripping details of what Dunham did on Apr. 14, 2004, and how his sacrifice changed their lives. (Photos courtesy of Three Branches Productions, LLC)

The film opens with Dunham’s family background. Dan and Deb Dunham are not his biological parents, and the film details how Dan came to adopt him. From a young age, Dunham learned what responsibility and a strong work ethic looked like as he watched over his younger brother and worked with his father on a dairy farm. His parents encouraged Dunham’s enlistment in the Marines. They understood, even before he graduated high school, Dunham needed a challenge to thrive; not a contest against others, but to continually challenge himself.

“We get a lot of credit for what he did,” Deb Dunham states in the film. “We don’t deserve that. We sent them [the Marine Corps] a young man that had a lot of good values. He went to the Marine Corps and the seeds that we prayed we had planted and would [grow] well, they blossomed, and the Marines polished what we gave them. Whenever people would say, ‘Are you a Marine?’ Jason would flash that grin and say, ‘You bet your sweet ass I am.’ He was proud of it. He was a Devil Dog, and that was what he wanted to be and do.”

The film proceeds into Dunham’s service in the Corps and eventual deployment to Iraq with Kilo, 3/7. One lesser-known fact emerges from the film; Dunham extended his enlistment so he could deploy to Iraq with his Marines.

The documentary covers the details of Dunham’s heroism and the events leading up to his final act of smothering a grenade with his Kevlar helmet. The two Marines next to him that day, Private First Class Kelly Miller and Lance Corporal Bill Hampton, describe what happened and reflect on Dunham’s his actions, as he traded his life for theirs. Other Marines who watched Dunham’s patrol leave the wire that day reveal the aftermath of the loss and how the details of his actions came to light. Stunning images of Dunham’s helmet, ripped to shreds, play alongside Marines’ descriptions of how they tried to process the day.

Much of the later portions of the film demonstrate precisely how Dunham’s actions continue to impact a growing number of people. Many of the Marines interviewed have battled guilt and post-traumatic stress. Dan Dunham describes his own bout with guilt following his decision to take his son off life support eight days after he was wounded.

Another perspective offered by the documentary comes from the spouse of a Marine who served with Dunham in Iraq. Becky Dean, the ex-wife of Marine veteran Mark Dean, participated in the film and described her former husband’s significant battle with PTSD in the years following his deployment in the hope of helping to demonstrate the tragic effects of war on the families back home.

“A lot of people don’t realize that PTSD is transferred to the kids and spouse,” said Kniess. “Especially the spouses. They are front and center. They get the brunt of it. Having Becky’s story included is something I think a lot of people out there will relate to.”

Perhaps the most powerful part of the story centers on a Kilo 3/7 reunion organized for the film. In September 2021, 3/7 Marines from across the nation gathered in the Dunhams’ driveway in New York before marching to the local cemetery where Dunham is buried. The candid remarks captured for the film on that occasion are both heartbreaking and inspiring, revealing the true extent to which Jason Dunham impacted the people who had the privilege of knowing him.

The production crew endured numerous hardships and setbacks filming during the pandemic but despite these challenges, Kniess reflected that the most difficult part of making the documentary was conducting the interviews. Month after month, interview after interview, Kniess and his team relived Dunham’s story with Kilo 3/7 veterans around the nation. Each time felt like opening an old wound. He knew it would be difficult for the Marines to relive that day. Kniess did not fully expect the emotional toll it would take on him. He saw it in the faces of his team as well. Tears flowed freely on multiple occasions, and heavy-hearted interviews ended with the team hugging the interviewee one by one and thanking them for sharing their story.

Healing emerged through the pain, however. The process of reliving and celebrating Dunham’s story held enormous therapeutic value for some. Jason Sanders, one of the Marines with Dunham on his final patrol in Iraq, offers a profoundly insightful view during his interview in the film.

“It’s kind of hard to give up your stories to someone who has never been involved in anything like that,” Sanders says. “It’s real hard to, because you’re sitting there wondering, I don’t think they’re really comprehending what the hell I’m saying, you know? And you can’t expect anybody else to know the feelings that you felt that day, because it’s not normal. You kind of have to let your guard down and let people help you.”

The difficulty of the interviews also played a role in naming the film. One of the cameramen working on the production team spent time as a combat photographer in Iraq, Afghanistan, and, most recently, Syria in 2018. The interviews with Dunham’s Marines brought back gruesome memories of his time as a combat photographer and drove him to tears.

“You need to call this thing ‘The Gift,’” he told Kniess one day after an interview concluded. “What Jason did was a gift. You’ve got children being born, families being started, and people who were able to go on and do things with their lives because of this gift.” As Kniess expanded the interviews, more and more people referred to “the gift” that Dunham had given them. By the time filming was complete, there could be no other title.

Dunham is recognized today through many tributes. Most notably, the U.S. Navy named a guided missile destroyer in his honor, USS Jason Dunham (DDG-109). Even so, in the years since he became the first Marine to receive the Medal of Honor since Vietnam, Dunham’s story has been largely overshadowed by later recipients perhaps because a surprising number of Medal of Honor recipients from the global war on terrorism survived to receive their medals.

“The Gift” documentary succeeds in rejuvenating Dunham’s story in a moving and relevant way. The Marines interviewed unanimously echo a resounding fact; Dunham’s sacrifice affects them more now than it did the day it happened. “There are two things I want people to get from this documentary,” Kniess said. “The general public, I want them to gain a better understanding of what it’s like for Marines and Soldiers to go to war, what they experience, and how it affects them. Everyone in uniform these days has had the experience of someone coming up to them and saying, ‘Thank you for your service.’ I don’t think a lot of people who do that really understand what those words mean. I don’t blame them or fault them for that. I think it’s great they take the time to say it, but I hope people will watch this film so the next time they say it, they will better understand what those words mean.

“As for the veteran community, I know there are still guys out there struggling. There’s going to be someone out there watching this, and they’re going to learn about some of the guys we interviewed, the drug addiction, all the things they went through, and how they turned their lives around. I’m hoping that veterans like that will watch this and think, ‘Well, if they did it, why can’t I?’”

“The Gift” was produced by Three Branches Productions, LLC, a veteran-owned production company. The company was founded by three veterans: Kniess, who served in the Navy; Vincent Vargas, an Army Ranger; and Anthony Taylor, a Marine. The fourth member of the team, a civilian, is executive producer Chase Peel. “The Gift” won Best Documentary at the Utah Film Festival in January, has been invited to the GI Film Festival in San Diego, Calif., taking place this month. Kniess received the Santini Patriot Spirit Award at the Beaufort International Film Festival in February for his role as director, and the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation’s Major Norman Hatch Award for best documentary feature. Three Branches produced two versions of the story, a two-hour feature length film, and a five-part series. “The Gift” will release on streaming media in spring 2023. Visit www.watchthegift.com for updated information about the release date.