“Go Down Like Marines”: The Ill-Fated Voyage of SS Henry R. Mallory

By: By Geoffrey W. RoeckerPosted on January 15, 2023

Private Marvin Elmer Muehl leaned against the steel bulkhead, feeling a shudder of relief as the metal chilled the sweat running down his back. Creature comforts were hard to come by in Hold No. 3, a space he shared with about 60 other Marines. The muggy air was rank with body odor, cigarette smoke, and the inescapable smell of seasickness. In other holds, hundreds of other men—soldiers, Sailors, and merchant mariners—were grimly suffering. The North Atlantic was angry this time of year; bad weather and blackout conditions kept most hands below deck as the SS Henry R. Mallory churned steadily eastward. Undercutting the boredom was an electric thread of tension: the ever-present threat of German submarines.

Muehl chatted with some buddies near the stairwell to the hold. Although almost 4 a.m. time, several Marines were too nervous to sleep. They had seen other ships in Convoy SC-118 erupt in balls of flame, and a midnight alert sent everyone scrambling to their lifeboat stations, wrapped up and shivering in the cold night air. In the close confines of Hold 3, stripped to their skivvies, the young men passed the last few hours of darkness speculating about what awaited them in Iceland.

The explosion lifted Muehl off his feet. “I was floating through the air,” he later recalled, “and then, for quite some time, everything was quiet. I realized that I was flat on my back lying next to the people I had been talking to and was being trampled on by people trying to get on deck through the opening where the stairwell had been.” He heard running water, smelled something burning, and saw his trousers soaked with blood. Muehl’s right leg would not bear his weight, but he dragged himself to the jagged hole through which his buddies escaped. A light shone down from above. Muehl hollered, and two men pulled him out of Hold 3.

“You’re on your own,” they said. “She’s going down fast.”

The sinking of the liner-turned-transport Henry R. Mallory on Feb. 7, 1943, was a tragic event in the convoy battles of the North Atlantic. Built in Newport News, Va., in 1916, Mallory was quickly pressed into service as an Army transport and spent two years carrying troops to and from French ports. Returned to the Clyde-Mallory line in 1919, she sailed between New York and New Orleans in civilian livery for more than 20 years. In 1942, Mallory was again requisitioned for convoy duty. She completed one round trip from New York to Reykjavik before her fatal encounter with Kapitänleutnant Siegfried von Forstner’s U-402. On her last voyage, Mallory carried a valuable cargo of tanks, clothing, cigarettes, and ammunition bound for Iceland; aboard were nearly 500 passengers and crew, 272 of whom perished at sea. Thirty of the dead were United States Marines—the only ones lost in the Atlantic convoys.

The Marine Corps had maintained a force in Iceland since the summer of 1941 when the 1st Marine Brigade (Provisional) was assembled for “temporary duty beyond the seas.” British troops on garrison duty were urgently needed to defend the Home Islands; the U.S. Army could not send draftees overseas in peacetime, so the Marines drew the job. While America and Germany were not formally at war, the threat was ever present. Iceland veteran Clifton J. Cormier, then a sergeant with “Fox” Battery, 10th Marines, noted that “only 700 miles across the North Sea in Norway were three German divisions. German reconnaissance planes occasionally flew over, drawing desultory antiaircraft fire” from British gunners. Despite the proximity to an armed enemy—and a few Nazi sympathizers among the younger civilians—Marines found Icelandic duty rather stultifying. Daily duties consisted of standing guard, unloading ships, and building huts with “only four hours of a sort of hazy daylight” to accomplish anything outside. Liberty options were limited to a handful of overcrowded restaurants and movie houses. The young ladies were “quite pretty,” but hopeful Americans had to contend with a language barrier, Icelandic customs, and a governmental policy forbidding any fraternization contrary to public morals. The Brigade’s morale, readiness, and discipline suffered from Arctic ennui.

Cormier recalled that the attack on Pearl Harbor was a “morale booster” because “the Marines would be heading for the Pacific where they belonged.” The Department of the Navy made preparations to redeploy the Brigade in early 1942; an Army garrison would take over their camps and installations. An allocation was also made for a small Marine unit to serve at the proposed Naval Operating Base Iceland (NOBI). The first Marine detachment, approximately 30 men led by First Sergeant Harry Fluharty, was organized overseas on Feb. 22, 1942. One month later, the last elements of the 1st Marine Brigade returned to New York, trading in their distinctive polar bear insignia for new assignments.

With the United States officially on a wartime footing, the construction of NOBI (formally Camp Knox, established May 16, 1942, on the outskirts of Reykjavik) progressed quickly. Soon, the base supported convoy shipping sailing between North America, Great Britain, and northern Russia. Seabees arrived in August to build a hospital, salvage facilities, an ammunition depot at Hvalfjordhur, a “tank farm” (fuel depot) at Falcon Point, and a Fleet Air Base at Skerjafjörður. A larger base required more guards, and by October 1942, the Marine Detachment numbered 121 officers and men. Although the new construction included recreational facilities at Falcon Camp, duty was scarcely more exciting than it had been for the 1st Marine Brigade, and “Ho-ho-hum, Iceland here we come” was sung loudly on liberty or under one’s breath while on duty. A tour lasted from 12 to 18 months; for the hard chargers and the homesick, the time passed slowly.

In January 1943, the next Icelandic detachment formed at the New York Navy Yard. A quartet of second lieutenants led the group; the senior pair, Henry Mears Hobbins and Paul Wilson Wolfe, were six months into their commission. Sergeant George Andrew Yanek, whose 23 years of age included five in the Corps, assisted as the senior enlisted man. The balance included two corporals, five privates first class, and 52 privates. Just two weeks before, most of the junior Marines were Parris Island boots; they came north via Quantico, where they were selected for Iceland by some forgotten criteria. “I was sent to the Brooklyn Navy Yard for assignment, although it had already been decided what my assignment would be,” recalled Private Joseph “Mickey” McMillen. The Canonsburg, Pa., youth enlisted on Nov. 7, 1942; now he was preparing to sail to a foreign land.

Once aboard, the Marines stowed their belongings in Hold 3 and made the most of their dwindling free time as Mallory took on cargo and passengers. Detroit-born Marvin Muehl could not get enough of Times Square, while Private John Edward Stott made the 200-mile round trip from Brooklyn to Norristown, Pa., on three consecutive nights. Stott, just 17 years old, was “very low in spirits” during these visits and “a little depressed” about the prospect of going overseas.

Some brought unique experiences to the gab sessions including Private Joseph Buono, a New York shipyard worker who survived the SS Normandie disaster. Private Arthur Bennett might have been close-lipped; he had spent time in Moyamensing Prison and the infamous Fairview State Hospital for “impersonating a G-man.” The Corps chose not to hold this transgression against Bennett when he enlisted in October 1941.

Mallory departed New York on Jan. 23, 1943, and set a course for Halifax where she joined other merchantmen and escorts assembled as Slow Convoy (SC) 118. “Slow” it certainly was; the average speed of a ship in SC-118 was a mere six knots, a third of Mallory’s capability. No other convoys included Iceland-bound sections, so Mallory was stuck with the slower ships. The prospect of a long voyage was most unwelcome to the enlisted men stacked in the holds. “The passage was miserable,” said Private Thomas M. Sullivan of Kansas City, Mo. “We never had one day of sunshine, and we were sailing in one of the worst winters in the North Atlantic. Our quarters were overcrowded, and the food served to us was abominable. I doubt that accommodations for the officers on board were much better than ours.” The ship’s master, Horace R. Weaver, was a seasoned Mallory officer but had never sailed in command. Boat drills, held every day and twice at night, were as much for the benefit of the inexperienced crew as the passengers. Author Michael G. Walling notes that these drills omitted crucial information: “Men reported to their lifeboat stations, but the boats weren’t swung out or tested, and the passengers were not shown how to lower them or what the boats contained for emergency supplies.”

While the first few days at sea were uneventful for the men aboard Mallory, their adversaries were assembling the formidable Wolfpack Pfeil II: 13 U-Boats led by veteran Korvettenkapitän Dietrich Lohmann. Decoded Allied messages revealed the route of SC-118, and a prisoner plucked from the sea confirmed a slow convoy: easy pickings for German torpedoes. Lohmann established a patrol line to intercept the freighters, but rough weather worked in the convoy’s favor and the submarines struggled to make contact. On Feb. 4, 1943, the Norwegian-flagged freighter Annik accidentally fired a star shell and was spotted by U-187. Escorts picked up the German transmission and sank U-187 for first blood; the next day, the American freighter SS West Portal was torpedoed and lost with all hands. Two more stragglers (Greek Polyktor and Polish Zagloba) were picked off on February 6. The battle for SC-118 was joined.

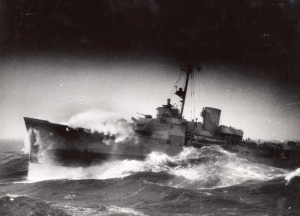

Survivors of a torpedoed vessel huddle beside the tiny mast that was rigged to their lifeboat as they prepare to board USCGC Bibb after being rescued in the North Atlantic. (USCG photos)

Joseph McMillen celebrated his 19th birthday aboard the Mallory on Feb. 3; now he was standing KP duty in the ship’s galley. As he carried a pail of garbage to dump over the side, he saw “a brilliant flash on the horizon; I guessed it was possibly a tanker,” or possibly the death throes of the Hopkins. Marvin Muehl noted, “We were getting quite nervous” even before a submarine alert sent all hands scrambling topside in coats and live preservers. When the alert secured, the men trooped back below to their quarters or headed to their guard posts. In the back of their minds was the knowledge that convoys never stopped to pick up survivors. That role was left to rescue vessels; they could not know that Toward was already gone.

The passengers were also blissfully ignorant of Mallory’s vulnerable position on the convoy’s flank. Maintaining a steady pace was difficult for a fast ship in a slow convoy, and Captain Weaver’s inexperience led to a habit of straggling out of position. Earlier that evening, the freighter Empire Squire maneuvered erratically and cut into formation ahead of Mallory, forcing the troop ship to cut her speed. As Walling writes, “For an hour or more, there was no ship outboard of Mallory in the convoy. She had three ships in sight and was between four hundred and a thousand yards astern of Empire Squire. One or two corvettes patrolled a mile and a half to two miles astern.” She was a tempting, almost inevitable, target.

U-402, her tubes reloaded after a successful first strike, reentered the fray by disabling the Norwegian tanker Daghild and sinking the British freighter Afrika. Less than 20 minutes after sending Afrika to her demise, von Forstner sighted in on a single-stacked vessel of about 6,000 tons. On his command, U-402 sent a 21-inch torpedo racing toward the target at 30 knots.

A grouchy galley cook saved the life of Marine Private Henry Filippone. He spotted a fresh blueberry pie cooling in the galley at chow time, only to be chased off by a sailor—pie was reserved for officers. “Pop” Filippone brooded over the pie for hours until he could take no more. Pulling on some clothes, he started up the ladder from Hold 3 and was on his way to the galley when 280 kg of high explosive slammed through the bulkhead where his buddies were berthed. Filippone hurried to the main deck to see what was going on.

It was a very different scene in Hold 3, where Marines were reeling from the force of the explosion. Mickey McMillen and Private Stanley Pasinski fell asleep chatting shortly before the strike; Pasinski was knocked out and “came to with a gash on my head. I don’t remember anything except climbing up through the hatch.” McMillen “woke to the sound of people yelling and screaming and much confusion.” He was napping on another Marine’s bunk, and when he looked at his own, “there was nothing there … I managed to get on deck and to my assigned lifeboat, but it was gone.” Still somewhat dazed, McMillen returned to Hold 3 to grab an overcoat. “I decided it was going to be cold on the water.”

McMillen’s decision was a smart one. Passengers on the Mallory were advised to sleep in their winter clothes, but the heat in the holds made that impossible. Private Donald Gross was sitting on the ladder when the torpedo hit, and said, “I don’t remember anything else until I came to in a lifeboat. Then I found that I had on only dungaree pants, a dungaree jacket over a sweater, and no shoes.” Private Gerald Moyer was trapped under collapsing bunks. “I managed to squeeze out, but my clothes were still under there,” he recalled. “I went up on deck with only a khaki shirt and dungaree pants.”

In the bunk directly above Moyer was 17-year-old John Stott. “I was thrown up against the overhead and knocked out,” he said. “I fell down on the deck, and when I came to, there was considerable water in the compartment. Something was wrong with my leg … I couldn’t put any weight on it.” Stott had the presence of mind to pick up a life jacket on his way to the gaping hole that led out of the hold. An unknown number of Marines were left behind in the hold, either killed by the explosion or too badly injured to escape the rising water.

Chaos reigned on the upper decks. Men raced to their assigned stations to find their boats gone, ropes fouled, or pressed against the hull by the increasing list. Only the merchant sailors had experience lowering boats, and none had practiced with Mallory’s equipment. To make matters worse, Captain Weaver issued no orders after the torpedo strike—no alarms, no flares, no radio calls, and no abandon ship instructions came from the bridge. Nearly 500 men were left to fend for themselves. With one of their assigned boats already destroyed, the Marines were in a particularly tough spot. A corporal—possibly Floyd W. Jerkins, a pre-war enlistee—gave the frightened men advice, a warning, and an appeal in one sentence: “If you gotta go down, go down like Marines.”

Mickey McMillen found his way to another lifeboat.

“When we reached the water, no one could figure out how to release it from the lines. Then someone found a hatchet and used that to cut the lines at one end. While passing it to the other end, though, the hatchet was lost over the side. The issue with the lines became moot, however, as we also discovered that the boat was filling with water since no one had closed the seacock. As the waves lifted the boat, guys would jump out of the lifeboat and back onto the deck of the Mallory.

“I was still in the lifeboat when an object landed in the water next to me; I jumped to it. I did not land on it but did manage to grab hold of it and climb aboard. Once aboard, I realized that it was a life raft, and soon it began to rain men jumping from the Mallory. When morning came, I counted 22 people on board.”

Privates Pasinski, John Behun, and Joseph Biedenach jumped from McMillen’s boat back to the Mallory, then found another floating by. “There must have been 50 or 60 of us in that boat,” Pasinski said. “We were so overcrowded that the boat was low in the water, and waves kept washing in and filling up the boat even more.”

Lt Barrick watched in dismay as “the first raft they tossed overboard sank immediately … a crewman and I cut loose another raft lying on the deck. We couldn’t lift it, so we decided to let it float off. The ship was settling by this time and some waves were coming over the deck. A big wave finally washed us overboard. I think the raft got off easier than any other on the ship, although I had been afraid it would be swamped.” Barrick and 2ndLt Howard H. Fisher were the only Marine officers to survive the sinking.

The Mallory went down by the stern and vanished about 30 minutes after the torpedo hit. Hundreds of men now struggled in the icy water as the convoy sailed on, oblivious to their predicament. The Germans were still shooting; U-402 would score two more kills (Greek freighter Kalliopi and British merchant Newton Ash), while U-608 finished the damaged Daghild. Wolfpack Pfeil II sank 12 of the 61 ships in SC-118, with U-402 accounting for seven. Kapitänleutnant von Forstner was awarded a promotion and the Knight’s Cross for this feat. The loss of three U-boats and the severe damage of several more led German Admiral Karl Dönitz to deem SC-118 “perhaps the hardest convoy battle of the war.”

None of this mattered to the desperate survivors of the Mallory as they clung to boats, rafts, and debris in the dark. Private Horace Melton, the “old man” from North Carolina, spent 30 minutes in the water before reaching a lifeboat. “There were 18 of us aboard at first,” he said, “but the sea was dragging them off as fast as [their strength ran out] and the rest of us couldn’t do a thing about it.” Joseph McMillen struggled to stand upright on his raft. “Once during the night, I fell out, but a sailor pulled me back on,” he said. “He and I helped each other stay balanced all night.” The raft rode nearly a foot underwater, and the men were buffeted by continuous rain and sleet. Men turned on their red rescue lights, and Mallory cook George Dunningham thought “it looked like some weird, strange dream to see all those little red lights bobbing up and down.”

Snow and sleet blanketed poorly clad survivors already drenched to the skin in their thin clothing. Men hanging to the sides of boats and rafts gradually weakened; they lost their grip and drifted away to drown. Superhuman efforts saved many other lives. Father Gerald Whelan, a Navy chaplain, recalled the bravery of one Joe Reilly in keeping their lifeboat afloat. “We also had two poor Marines, legs broken, their faces damaged badly,” he recalled. “How they got into the boat I don’t know, but someone should have gotten the Soldier’s Medal for their rescue.” One of these Marines was probably Marvin Muehl, who suffered a fractured tibia in the explosion. The hours passed slowly; the sky began to lighten. There was little else to do but cling to faith, fast-dwindling hope, and anything that would float in the rough seas.

To the men afloat, the modest Bibb was a wonderful sight, “The most beautiful ship in the whole world,” in George Dunningham’s opinion. “I can’t tell you how wonderful she looked.” Raney maneuvered the cutter “like a New York taxi” to block the worst of the wind, and exhausted survivors were hauled aboard with ropes under their arms. Muehl and McMillen both came aboard in such fashion; Muehl was rushed to sick bay, while McMillen went to the boiler room to dry out and sample his first-ever cup of black coffee. Private Melton, “almost dead of cold, fatigue, and exposure,” was hauled aboard the Bibb; he was one of only six men on his raft to survive.

Coast Guardsmen not directly involved with the rescue stared in horror at the scene before their eyes. “We drove right through masses of humans. Each one wore a red light on his life jacket on the left side,” said one. “I saw men bare from the waist up,” said another. “They were dead, of course. They were purple; we couldn’t do anything for them.” Rafts full of motionless bodies were searched, and Coasties pulled dog tags from lifeless men. Second Lieutenant Harry Hobbins was the only Marine identified in this manner; he “died on a raft at sea of wounds received in action.” The Bibb had neither time nor space to bring bodies aboard, and Hobbins joined hundreds of shipmates on the bottom of the Atlantic.

Wally Cudlipp, a Bibb crewman, remembered seeing a Marine clinging to a floating door. “Our skipper, Captain Raney, said ‘I want to rescue that man if we don’t rescue another one. He really wants to live. Let’s get him.’ So, I jumped in a raft with a few other guys, and we starter to lower it when somebody hollered ‘Periscope!’” The lone cutter was a tempting target for any German submarines still lurking in the area, and Bibb—first and foremost an escort vessel—suspended rescue operations to give chase. In this case, a lookout mistook the mast of a lifeboat for a periscope. Bibb returned to her work, but the short delay was fatal to some. “When we came back to pick this Marine up, he had slipped under,” Cudlipp concluded.

Help arrived in the form of USCGC Ingham and Royal Navy corvettes Campanula and Mignonette. While the corvettes provided cover, Ingham moved slowly through the water searching for signs of life. “The ocean was covered with litter and dead soldiers,” said one of Ingham’s crew. “They had their life jackets on, and they’d float up and down with the waves.” The escort commander repeatedly called Bibb to rejoin the convoy; Raney responded with a curt “Go to hell. We’re not leaving here until we get every man in the water.” After hours of effort, Bibb rescued 202 men and Mallory’s dog, Ricky. Ingham picked up 20, and the British ships four each. Astonishingly, later that same day Bibb rescued another 32 sailors from Kalliopi. Crammed to the bulkheads with nearly 540 men aboard, the cutter resumed her place with the convoy, screening for submarines.

Despite the efforts of medical personnel, five Mallory men died of wounds and were buried at sea. Private John William Miller, Jr., a 30-year-old Marine from Highland Park, Pa., was among them. In keeping with naval tradition, each man was sewn into a canvas sack weighted with a 5-inch shell and was committed to the deep after a brief service. Like many other Marines on Mallory, Miller had been in uniform for less than three months.

The Iceland-bound ships finally arrived in Reykjavik on Feb. 14, and the survivors gratefully stood on dry land once more. Of nearly 500 men who left New York on the Henry R. Mallory, only 230 survived the convoy ordeal. Thirty Marines were lost, including Lieutenants Hobbins and Wolfe, the experienced Sergeant Yanek, the reformed conman Arthur Bennett, and 17-year-old Martin Finn. Several others were hospitalized for broken bones, frostbite, shock, and mental observation. Private Marvin Muehl’s fractured leg was a ticket home for a disability discharge, as were Private Melton’s numerous injuries and those of six other Marines.

Those fit for duty were soon integrated into the Marine Detachment at NOBI and began a blessedly uneventful 12-month tour. On Feb. 1, 1944, the number of Marines in Iceland was cut in half, and the Mallory survivors were among the contingent ordered back to the United States. A few would see combat in the Pacific, and some went on to long careers; Barrick and Sullivan both retired as colonels. For the most part, those who escaped the Mallory—men like John Stott, Stanley Pasinski, Gerald Moyer, and Joseph McMillen—served out the rest of their time Stateside and rarely spoke of their wartime experiences.

Today, the names of the 30 Marines lost with the Henry R. Mallory are inscribed at the Cambridge American Cemetery in Coton, England—the only such memorial for Marines lost in the Atlantic.

U-402 was destroyed by aircraft from the USS Card on Oct. 13, 1943. She went down with all hands, including 33-year-old Sigfried von Forstner.

Private, Paterson, N.J.

Albaugh, Roscoe Harrison

Private, Akron, Ohio

Bennett, Arthur Abraham

Private, New York, N.Y.

Buono, Joseph Alfred

Private, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Cobb, Edward Charles

Private, Cincinnati, Ohio

Dunfee, George Donald

Private, Belmont, Ohio

Eaton, Melville Bates

Private, Watertown, Mass.

Famularo, Lawrence William

Private, Oswego, N.Y.

Finn, Martin Christopher

Private, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Frye, Elmer Muncie

Private, Greensboro, N.C.

Gehret, Harry Eugene

Private, Philadelphia, Pa.

Heckathorn, Boyd Wesley

Private, Findlay, Ohio

Hobbins, Harry Mears, Jr.

Second Lieutenant, Oak Park, Ill.

Hunt, Edwin Lester

Private, Kingston, Ohio

Jenkins, Willie Edison

Private, First Class, Wylam, Ala.

Jennings, James Robert III

Private, Spartanburg, S.C.

Jerkins, Floyd Willard

Corporal, Tampa, Fla.

King, Robert David

Private, Kalamazoo, Mich.

Laibman, Alvin

Private, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Lott, Lawrence Allen

Private, McKeesport, Pa.

Maujer, Joseph Henry

Private, Richmond Hill, N.Y.

Miller, John William, Jr.

Private, Highland Park, Pa.

Potts, William Raymond

Private, Bridgton, Maine

Roach, William Reges

Private, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Rogowski, Harry John

Private, Buffalo, N.Y.

Sopp, John Frederick

Private, Erie, Pa.

Surina, Stephen Anthony

Private, Jamesville, NY

Weaver, David McClain

Private, South Fork, Pa.

Wolfe, Paul Wilson

First Lieutenant (posthumous),

Marshalltown, Iowa

Yanek, George Andrew

Sergeant, Youngstown, Ohio

For more information and pictures of the Marines who were lost, visit: www.missingmarines.com.

Author’s bio: Geoffrey W. Roecker is a frequent contributor to Leatherneck and is the author of “Leaving Mac Behind: The Lost Marines of Guadalcanal.” His extensive research into missing World War II-era personnel is available online at www.missingmarines.com.