EMLCOA 2.0

Posted on July 18,2019Article Date Dec 01, 2013

By Maj Roberto Scribner& 2ndLt Patrick Terhune

The current approach to teaching and executing the enemy’s most likely course of action (EMLCOA) analysis at the company grade officer level is flawed because it allows cognitive traps to stifle empathy and creative thought. A new methodology is required that eliminates those traps and provides an improved framework for envisioning how the interactively complex system made up of enemy forces, friendly forces, terrain, missions, and moral factors act in a particular time and space. Mirror-imaging-the assumption that the subjects being studied think, process information, and see the world in the same way as the analyst-is perhaps the most common cognitive trap in conducting EMLCOA analysis. The Basic School (TBS) trains company grade officers to develop an EMLCOA by “turning the map around” and “putting themselves in the enemy’s shoes.” Using METT-TC (mission, enemy, terrain and weather, troops and fire support available, time, civilian considerations) analysis, lieutenants and captains predict the enemy’s mission; how they will try to achieve that mission with past, current, and future actions ; and how they will react to contact.1 The current methodology leads to order-writers reflecting the actions that they as Marine officers would take if placed in the same situation as the enemy, rather than how the enemy, who does not think and act like a Marine officer, will act.

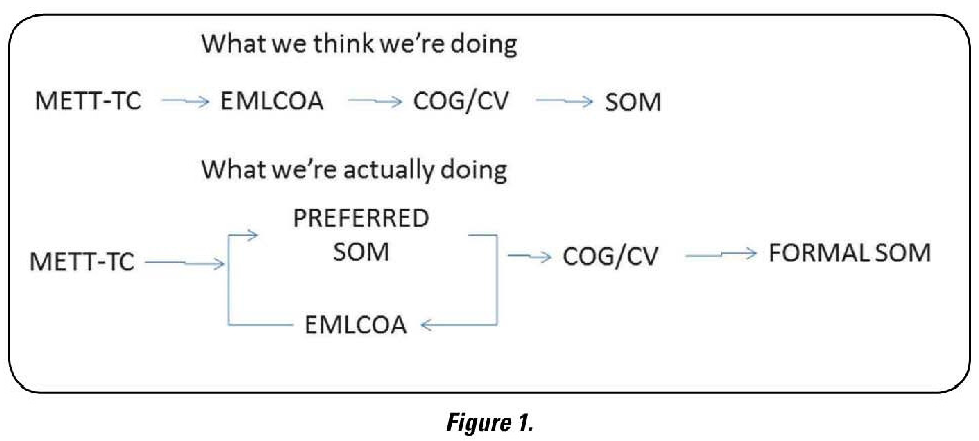

Training documents state that the EMLCOA is critical because it is central to the development of the center of gravity/critical vulnerability (COG/CV) and the scheme of maneuver (SOM).2 Additionally, the EMLCOA is the first creative narrative the junior officer presents in the operations order, making it highly in>Maj fluential to subordinates. In reality, our focus group research showed that the EMLCOA is part of a self-referential decisionmaking loop because the orderwriter has already chosen a preferred SOM to which the enemy will react to write the EMLCOA (see Figure 1). The order-writer develops a SOM based on the EMLCOA, and the EMLCOA is based on a SOM that the writer already has in mind while conducting the METT-TC. Our focus groups showed that the current approach to teaching and developing EMLCOAs (hereafter termed “EMLCOA 1.0”) leads to a middle-of-the-road approach that ascribes insufficient agency to the enemy, resulting in poorly developed analysis that falls into multiple cognitive traps. EMLCOA 2.0 is a focus group-tested methodology for teaching and conducting EMLCOA development using redteaming techniques that vastly improves the breadth and depth of analysis as well as eliminaring mirror-imaging and greatly expanding how junior officers think about the enemy.

The authors administered the included tactical decision game (TDG) (see p. 47) to 23 second lieutenants indoctrinated in EMLCOA 1.0 development at TBS.3 When initially instructed to develop an EMLCOA, the responses showed remarkable similarity with only two respondents deviating slightly from the norm by assuming that the enemy would send out patrols. The following paragraph contains the elements with 75 percent or greater commonality from the respondents’ EMLCOA 1.0 and divides the EMLCOA 1.0 into three statement sets, [SI] through [S3]:

[Si] l’he enemy is a .squad-sized element of Centralian Revolutionary Forces (CRF) [S2] set up near the top of Hill 293 buc within 300 meters of North Bridge to ensure the bridge is in AK-74 range.4 The enemy’s mission is to keep us from crossing North Bridge. They’re dug in about chestdeep in a semicircular battle position oriented east toward the bridge. Their PKM (medium machine gun) has a principal direction of fire (PDF) on the bridge. The 50mm mortar is ser up on the military crest opposite the bridge on Hill 293. They’re at 25 percent security. They have a two-man listening post/observation post (LP/ OP) on Hill 74 to watch their southern flank. [S3] Right now they’re eating chow and improving their defensive positions. When we attack tonight they’ll be at 25 percent security and will defend fiercely until they take 25 percent casualties, at which time they will withdraw to the west to link up with their parent unit.

All respondents stated that they had developed a preferred SOM prior ro EMLCOA 1.0 development.5 The respondents then consciously or unconsciously structured the enemy’s actions to serendipitously allow for the platoon’s use of a combined arms attack that maximized the use of indirect fire and automatic weapons. Additionally, the officers based the EMLCOA 1.0 on what they would do if they we rein charge oí a Marine squad given the enemy’s task, which they took to be countering the preferred friendly SOM that they had already imposed on the situation. Respondents mirrorimaged and ignored the likelihood that the CRF could maneuver through the swamp trails, would be unlikely to place themselves in the perfect position for the Marines to conduct a combined arms attack, and that the squad did not have to maneuver as a unit. The following analysis examines each statement set.

In [Si], respondents assumed the CRF squad acted as a single unit, maintaining centralized command and control to maximize mass and simplicity because that is how they are taught to employ it. The respondents ascribed the characteristics of a Marine squad to the enemy. In [S2], the respondents took their preferred SOM and created a scenario where the enemy, imbued with the characteristics of a Marine rifle squad, responded to that SOM. If the respondents commanded a Marine squad placed in the enemy’s situation, they would look for an obstacle where they could bring all their firepower to bear on a canalized enemy while maintaining standoff to protect themselves. Hill 293 fits these criteria. Because there are only two crossing points and the platoon may not be able to traverse the swamp in the time available, the enemy will be at North Bridge because that is where the platoon will be. In [S3], 25 percent security ensures that Marines man the automatic weapons at all times and that the unit gets adequate sleep. The respondents’ training teaches them to go to 100 percent security at end evening nautical twilight and begin morning nautical twilight, and since the platoon is attacking at night, the CRF will be at 25 percent security, per Marine standing operating procedures. The CRF are conducting the continuing actions taught to the respondents. The enemy will fight, of course, but the respondents believe from their casualty evacuation exercises that four injured Marines likely triggers abort criteria since manpower is consumed by carrying the wounded or dead. Thus, once the enemy sustains a similar casualty ratio, they will cease fighting while they arc still capable of withdrawing.

To achieve better EMLCOA analysis, mirror-imaging must be eliminated; the enemy must be ascribed the appropriate level of agency to do what is most effective for its own ends; and moral, psychological, and emotional states of the actors on the battlefield must be taken into account. Ehe EMLCOA 2.0 methodology evolved through experimentation and multiple failures, and is based on two key principles:

* The discourse of analysis itself is tremendously important. We found that it was critical to force the analyst to use the personal pronoun as the enemy leader when conducting analysis. Using”!” instead of “they” changed how willing the respondents were to ascribe agency to the enemy and develop courses of action that would defeat the friendly forces. In the words of one focus group member, “When you say ‘I’ and make yourself the enemy squad leader, it makes you want to win.”

* The enemy wants to win. Previous versions of the methodology failed in focus groups because respondents wanted the friendly forces to win more than they wanted to conduct a creative analysis that allowed for the possibility of enemy success. The first principle assists in breaking this bias, but it was critical to unfetter the respondents’ strong desires to limit the agency of the enemy to be as effective as possible. We overcame this by developing a step in the methodology where the respondent is directed to make the friendly unit fail in the most unpredictable way they can think of.

EMLCOA 2.0 can be accused of being a way to develop an enemy’s most dangerous course of action (EMDCOA) vice EMLCOA. EMLCOA 2.0 assigns intelligence and agency to the enemy, assuming that the enemy will take those actions that best lead to success as defined by that enemy. We argue that in a contest of wills that can lead to death, the enemy will do their utmost to win; to think that they will do any less is disingenuous. This may result in a merging of EMDCOA and EMLCOA, and we feel that this is completely acceptable. It is important to remember that conducting EMLCOA analysis does not excuse the analyst from understanding how the enemy’s doctrine may shape or constrain action and decisions. Doctrine can supersede creativity, and the analyst must understand when this is the case for a particular opponent.

EMLCOA 2.0 Process

When to use. This analysis should be conducted after the METT-TC process is complete.

Process narrative. This analysis will force the order-writer to look at how the enemy sees the friendly unit via a modified “Four Wtys of Seeing.”6 The writer will use this information to develop an enemy estimate of the friendly SOM. This method emphasizes gaining an understanding of how the enemy sees the friendly unit’s approach to solving the problem. The order-writer develops a narrative of how the enemy counteracts the friendly unit’s SOM in the most unpredictable way imaginable. Lastly, the order-writer writes a first-person narrative from the perspective of the enemy unit leader that begins 24 hours prior to contact with the friendly unit and ends 12 hours after contact. The first-person narrative continually forces the orderwriter to abandon mirror-imaging and identify with the enemy commander. Extending the preaction and postac- tion timeframes accounts for a major portion of the enemy’s planning cycle at the small unit level.

The method. (Note: When conducting EMLCOA 2.0 analysis, the “enemy” is the unit to which you, the analyst, belong. In the TDG, that makes the analyst the CRF squad leader and the “enemy” the Marine platoon.)

Step 1. Complete the METT-TC analysis.

Step 2. Using the pronoun “I” or “we,” write down how you, the unit commander, see yourself and your unit. Focus on how you view your strengths and weaknesses. Explore strengths and weaknesses that are physical, tactical, moral, psychological, and emotional. Think about your fears and what your unit can do well and what it does poorly.

Sample responses from the focus groups: We are light, fast, dedicated, and know the terrain well, especially the swamp near the south bridge. Although ive lack heavy weapons or the ability to deliver indirect fire, we have excellent patrolling and reconnaissance skills and can skillfully execute an ambush. We can melt away and appear anywhere we want. Were comfortable operating in smaller units without a lot of direction. We don’t want to die and since there are not many of us, we want to live to fight another day. We’d rather cause minor damage and then withdraw a hundred times vice standing andfighting and giving you a chance to use your superior firepower. We don t have to follow any RGBs [rides of engagement]’, so we can take the most effective actions without worrying about being investigated. I’m fighting on my home turf and I have to live here after you ‘re gone, so I care more. God is on my side and we deserve to win. My family and friends support me 100 percent in what I’m doing and I don’t want to let them down. If I fail, my family may suffer consequences from the invaders.

Step 3. Using the pronouns “you” or “they,” write down how you see the enemy you are fighting. Focus on how you view their strengths and weaknesses. Explore strengths and weaknesses that are physical, tactical, moral, psychological, and emotional. Think about their lears, and what they can do well and what they do poorly.

Sample responses from the focus groups: You are well-equipped andphysically tough fighters who understand techniques, tactics, and procedures (TTPs). You have capabilities we don’t even know about or understand. Your ability to call for indirect fire or air support gives you a huge advantage. You have excellent communications equipment that allows you to talk to each other over long distances. You have a platoon and we have a squad. You have better weapons than we do. You. carry too much stuff and this makes you move slowly and noisily. You’re very concerned with casualties and this makes you cautious and leads you to try to use the biggest guns you havefirst. Your night vision capabilities are excellent, but you think that because you have them that you have an advantage at night. You like to stay close to another friendly unit, road, or landing zone in case you have casualties or you need help. You have restrictive ROEs and worry a lot about how to follow them instead of just fighting the most effective way possible. You’re leaving when you’re done fighting, so you care less than I do. You miss your families and you’d rather be back with them than out here fighting me. You can show up anywhere by using helicopters. You have a couple of ways of doing things and you stick to them, even when the situation says that you should do something new or different. You publish all your TTP on the Internet so I can read them.

Step 4. Compare the results of step 2 and step 3 and note areas in which you think you have an advantage. Use the pronoun “I.”

For example: I have speed, better reconnaissance capabilities, stealth, and better ambush TTP. I operate well in fire teams or smaller units, so I in more mobile. I have the ability to function with missiontype orders and limited communications. 1 am not dependent on outside forces. I want to win more than you do because this is my home.

Step 3. Compare the results of step 2 and step 3 and note all places where the enemy may have the advantage. Use the pronouns “you” or “they.”

For example: You have firepower, indirect fire capability, communications technology, night vision, inter- and intraunit coordination, and much bigger unit size. You can use helicopters and vehicles to show up in unexpectedplaces very quickly.

Step 6. Based on the relative mismatches you sec in steps 4 and 3, draw or write down the SOM that you believe the enemy unitwill execute. Continually reference steps 2 to 3 to ensure that the SOM you arc building fits your previous analysis.

Step 7- Based on steps 2 and 4, which gave you how you view yourself, and step 6, the probable enemy SOM from your perspective, sketch out your plan to cause the enemy mission failure in the most unpredictable way you can think of. You can either write it step-by-step or draw it graphically on a map.

Step 8. Take a few minutes and create a movie in your head of how the SOM you developed in step 7 unfolds. Write a first-person narrative (a story) from your perspective on how the plan you came up with in step 7 unfolded. Begin 24 hours prior to making any contact and end 12 hours after making contact. This narrative is your EMLCOA.

Results

EMLCOAs using the EMLCOA 2.0 methodology exhibited a variety of creative, highly effective, and plausible solutions. All were different from the EMLCOA 1.0 analysis produced by the same focus group participants. Almost all focus group participants immediately destroyed the northern bridge, stating that the enemy needed the bridge but that the CRT did not. Several participants destroyed both bridges. Some destroyed both bridges and then waited to bait and destroy a potential heliborne force by either setting up ambushes in, or mining, landing zones. Those that did not initially destroy the northern bridge destroyed it later with a small team or explosives while the enemy crossed the bridge, splitting the enemy forces, which were then attrited through ambushes. Great care was taken to ensure that when direct combat occurred, the CRF undertook mitigation of enemy fire support assets. This varied from using terrain to keeping the enemy within the 60mm mortar effective casualty radius while fighting and then breaking contact in multiple directions. Participants broke their squad into hunter-killer teams to harass the enemy, laid ambushes, and used the swamp to maneuver into the enemy’s rear to strike. Several participants attempted a spoiling attack on the enemy’s assembly area or used attacks from the rear to force the enemy to pursue small teams into the swamp. Two participants independently developed versions of Che Guevara’s guerrilla “minuet.” The use of ruses abounded. Participants lit fires in various areas to either draw attention or to neutralize enemy night vision capabilities. One participant lit the northern forest on fire and then destroyed both bridges.

Focus group members made significant leaps in their analytical capabilities expressing and incorporating highly advanced concepts that they had not been previously exposed to such as important elements of systems thinking. Respondents stated that using EMLCOA 2.0 forced them to sec that there were multiple ways to interpret each element on the battlefield. In speaking about the northern bridge, one respondent stated:

Ic had more meanings [during EMLCOA 2.0], and [the meaning] just depended on how I looked at it. I could really jack up the Marines if 1 made the bridge mean something different to me than them and surprise the hell out of [the Marines].

The parallels between this and other like responses from our locus groups and then-BGen Aviv Kokhavi’s’s now classic discussion of conceptualizing space is instructive as to how creative junior officers can be when they are truly allowed to think:

This space that you look at, this room that you look at, is nothing but your interpretation of it. Now, you can stretch the boundaries of your interpretation, but not in an unlimited fashion, after all, it must be bound by physics, as it contains buildings and alleys. The question is, how do you interpret the alley? Do you interpret the alley as a place, like every architect and every town planner does, to walk through, or do you interpret the alley as a place forbidden to walk through? This depends only on interpretation. We interpreted the alley as a place forbidden to walk through, and the door as a place forbidden to pass through, and the window as a place forbidden to look through, because a weapon awaits us in the alley, and a booby trap awaits us behind the doors. This is because the enemy interprets space in a traditional, classical manner, and I do not want to obey this interpretation and fall into his traps. Not only do I not want to fall into his traps, I want to surprise him!”

Red-teaming methodologies must fundamentally and forcefully unhinge the accepted reality of the analyst to allow the viewing of a situation from a different frame of reference. EMLCOA 2.0 is an attempt to create a sufficient break with perceived reality for the company grade order-writer. It is necessarily simple because most company grade officers lack full-fledged intelligence cell support are often tasked with rapid mission planning cycles due to their place at the end ol larger unit planning cycles. EMLCOA 2.0 effectively creates empathy for the enemy’s point of view and capabilities, allowing company grade officers to quickly and effectively develop an EMCLOA without falling into cognitive traps. Focus group participants universally developed a better conceptualization of how the enemy might fight the Marine forces. At a deeper level, focus group participants increased the complexity and depth oí their thinking about the relationship of the elements on the battlefield and began to visualize these elements as part of a nonlinear, interactively complex system. Their EMLCOAs reflected enemy solutions to the problem that went beyond the mere application oí firepower and movement to space and time evidenced in EMLCOA 1.0 and encompassed psychological and moral factors in creative ways.

Notes

1. The introduction to EMLCOA in this publication states, “Based on your understanding ol the situation through the detailed analysis (METT-TC), turn the map around and ask yourself, ‘What would I do il I were the enemy?”‘ See Commanding Officer, Tactical Planning B2b2367/B2b2d87 Student Handout, The Basic School, Marine Corps Base Quantieo, pp. 9 and 20.

2. Commanding Officer, Combat Orders foundations B2b2377 Student Handout, The Basic School, Marine Corps Base Quantieo, 2012, pp. 12 and 14.

3. This involved administering the I DG to several focus groups. The TDG was first administered with instructions to the participants to simply perform a METT-TC analysis and EMLCOA in the manner that they had previously been taught. Results were then verbally collated by having the lieutenants individually brief their EMLCOAs. The same TDG was then administered using the EMLCOA 2.0 methodology. The examples for each step were not utilized in the conduct of the TDG. These examples were drawn from execution of the TDG itself.

4. The CRF, a guerrilla force, is one of the enemy forces faced by TBS students.

5. There was one SOM with minor variations: the platoon moves northward through the Eastern Forest, pauses before unmasking east of the bridge, uses the company 60mm mortars to suppress the enemy on I lili 293 in order to cross the bridge, and then conducts a fix-and-flank maneuver on the main enemy positions on Hill 293 before reducing the listcning/obscrvation post on Hill 74.

6. University of Foreign Military and Cultural Studies, Red leant Handbook, version 5, Fort Leavenworth, KS, 2011, p. 135.

7. Weizman, Eyal, “Lethal Theory,” Open, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2010, pp. 82-83.