Combat Service Support in Transition

Posted on August 14,2019Article Date Jun 01, 2002

by Capt Robert S. Burrell

With all the changes and proposed changes to combat service support (CSS) in the past decade, the development of the force service support group (FSSG) has made some jagged turns. Although proposals are adopted and modified, the future structure of the FSSG remains unclear, and there seems to be no consensus on its evolution. Without a unified vision, the 1st, 2d, and 3d FSSGs continue to test new ideas-which often differ from each other. CSS is currently in transition, but some of the changes being made at the operational and tactical levels appear contrary to maneuver warfare principles of task organization, decentralized control, simple and flexible planning, mission tactics using mission type orders, and initiative-based direction.

Doctrine and Conceptual Employment

Since World War II (WWII) the success of the Marine Corps can be attributed to its combat readiness, technological superiority, and logistical might. After the Cold War, budgetary restrictions forced the Marine Corps to reexamine its way of doing business. The emphasis on technology remained, but Congress considerably diminished the Corps’ capacity to purchase, store, maintain, and transport large quantities of material and equipment.1 CSS compensated for shrinking resources through a philosophy of “precision logistics.” The term precision logistics has been used to encompass such a diverse assortment of changes to the Armed Forces that the phrase has lost much of its original meaning. In this article I refer to precision logistics as the solution the Corps embraced for its decreased resources-in essence, the cliche of “doing more with less by fighting smarter.” It is important to note that precision logistics was not introduced because of its superiority to the time-proven lessons of WWII, Korea, and Vietnam, but because financial constraints made change necessary.

In the current environment of budgetary and manpower constraints, FSSG headquarters develops comprehensive operational plans that manage every aspect of CSS down to the last Marine and smallest piece of equipment. Essentially, current contingency plans fragment the FSSG into minute pieces and then glue it back together again for its wartime employment. This is the case for both contingency plans 5027 and 1003. In time of war the FSSG expects these blueprints to be meticulously implemented. It makes perfect sense for logisticians to plan as precisely as possible, but as I will demonstrate, the limitations of an exact logistical solution do not complement maneuver warfare.

Support of a rapidly maneuvering ground combat element or aviation combat element should primarily rely on the principles of speed, decentralized command, and multiple capabilities rather than precision. For example, maritime prepositioning ships (MPS) demonstrate a reliable logistics methodology in support of maneuver warfare. MPS revolutionized amphibious capabilities by its ability to convey a diverse assortment of logistical assets when and where they are needed. MPS can employ singularly or in groups, but they do not offer a specific remedy for any situation, and it would entail a lengthy process to do so. Instead, the ships are preloaded in several configurations and stationed at multiple locations. The Marine Corps justifies the enormous expense of MPS by demonstrating its ability to project logistical support worldwide at a moment’s notice. Of immense importance to the combat elements, MPS supports maneuver warfare because it employs fast and delivers the most essential items. However, it does not offer a precise (or economical) logistical solution.

In an organizational sense, the slimming and trimming of precision logistics have made rapid employment of the FSSG impractical. If anyone needs evidence of the FSSG’s current dilemmas, they need only study the table of equipment (T/E) and table of organization (T/O). In actuality, these Headquarters Marine Corps (HQ,MC) documents run contrary to the FSSG’s wartime employment. To compensate for peacetime responsibilities, the three FSSGs assign the majority of military occupational specialties (MOSs) and their respective equipment to single units. Hence, units such as transportation support battalion consist of most transportation assets; engineer support battalion retains engineer assets; the majority of administration is placed in one company, food services in another, communications in another, and so forth. This process occurs for nearly every MOS and its respective equipment.

So how does the FSSG function with a peacetime organization that is incompatible for war? Shortly stated, the FSSG has responded to the challenges of minimized available assets by creating a new unit for each assigned mission. The process of organization begins when the FSSG is assigned a supporting role in an operation. When this occurs, representatives are gathered from each major CSS field to conference until the manpower and equipment required to support the operation are established. Essentially, the FSSGs create a new T/O and T/E for each deploying unit from scratch without any regard for the group’s current administrative organization. Through this process the FSSGs intend to specifically tailor the force required while conserving their available assets for garrison functions.

The current FSSG system of creating new units for operations has frequently been referred to as “task organization.” However, that term has been inappropriately applied and needs correction.2 Task organization requires a standing base unit that subsequently absorbs reinforcement. In contrast, the notional CSS detachments (CSSDs) in FSSG contingency plans do not currently exist in any form. Far different from task organizing, contingency plans create entirely new CSS units for employment.

Creating a new unit to explicitly meet the requirements of an operation may be feasible, but this attempt at precision makes the employment of CSS complicated, slow, and inefficient. Depending on the size of the operation, the process of organization could take weeks and probably should take months. Each section within the FSSG takes the newly created manpower allocation table and fills those line numbers as best they can. The process simply picks Marines at random and pulls them from their current units. Now, imagine assembling thousands of personnel who have never worked together before and demanding that they accomplish a CSS mission within a short period of time! The determined nature of the Corps has made such efforts possible in the past, but this approach should be one of last resort-not one of choice.

History demonstrates the foolishness of rearranging personnel structure for wartime employment. I could discuss the adverse experiences of the Germans in WWI or MajGen A.A. Vandegrift’s difficulties in preparing for Guadalcanal in WWII, but I believe common sense alone can prevail on this point.3 Simply stated, a thorough knowledge of one’s subordinates is a prerequisite to the mission orders that make maneuver warfare possible. That begs the question: how can implicit trust be formulated with strangers who have been immediately thrown into the chaos of deployment?

In regard to equipment, dictating the needed vehicles and principal end items in support of a given operation is relatively easy, but assigning the numerous smaller items can be a daunting task. A finalized equipment table could consist of hundreds of thousands of items. Even after the generation of the initial list, an extensive process of revision needs to be implemented so that commanders, and others with expertise within the FSSG, can make suggestions. Making a T/E for a unit of any size is a timeconsuming process, but the FSSG hurries to implement extensive equipment tables for contingency plans by slapping them together in a matter of weeks.

Despite Herculean efforts, the current process of rearranging the entire FSSG in contingency plans does not produce the desired result of a precise logistical solution. The manpower and equipment tables that the FSSG creates for its plans remain questionable because the notionally designed units are untested. If the history of warfare has taught us anything, it is that untried units will have both excesses and shortages in critical manpower and equipment that will not be discovered until employment. Furthermore, when the time comes to rapidly support an expeditionary operation, the FSSG will be forced to implement whatever existing contingency plan that most closely resembles the realworld situation. Consequently, the force that the FSSG finally employs will not provide a precise solution to the actual CSS requirements. Because of time constraints, the intent of creating the “just right” CSS package is not achievable by the current system. And, I would argue that the exactness being pursued is not necessary or even a desirable aim of maneuver warfare. For unless the force commander can determine his route of advance, fuel requirements, equipment losses, repair parts, expended ammunition, and casualties in advance, it will remain impossible to “precisely” support a rapidly maneuvering combat element in the chaotic environment of war.

In the effort to conserve resources, the FSSG has sacrificed maneuver warfare on the altar of precision logistics. Mission orders have little relevance or importance in FSSG planning. Because the organizations that the FSSG will deploy in war do not actually exist, there is no scrutiny of mission orders and, in my experience with contingency plans, mission orders have frequently been overlooked altogether. Instead, wartime employment emphasizes the time– phased force and deployment data (TPFDD) needed for the FSSG to reorganize itself. The TPFDD has become more than the product of planning-it has become the sole purpose of it. To effectively support maneuver warfare, preparation for CSS should underscore personal relationships and training rather than imposing strict order on manpower and equipment.4

Reorganization

The three FSSGs should take a second look at the purpose of HQMC’s Tf O and T/E. Equipment and personnel should be assigned to standing subordinate units that are already task organized to accomplish designed combat functions. In other words, the administrative organization of the FSSG should be tailored to rapidly respond in support of the five basic types of Marine air– ground task forces (MAGTFs). To quote Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1 (MCDP-1), Warfighting, “Operating forces should be organized for warfighting and then adapted for peacetime rather than visa versa.”5

Similar changes have been proposed to the structure of the FSSG over the last two decades.6 In October 1991 Carlton W. Meyer wrote an article in the Marine Corps Gazette, entitled “The FSSG Dinosaurs,” in which he proposed a three-tier partition of the FSSG into brigade service support groups (BSSGs).7 Meyer envisioned the following for Ist FSSG: BSSG-7 would be stationed in Twentynine Palms and be tailored for MPS operations and support the Combined Arms Exercise (CAX); BSSG-5 would be stationed at Camp Pendleton in overall support of I Marine Expeditionary Force (I MEF); the third brigade would encompass Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) Service Support Group 11 (MSSG-11), MSSG-13, and MSSG-15. Although some may argue that the brigade emphasis in Meyer’s plan is outdated, several aspects of his pitch are worth noting. Principally, by giving depth to the organization of the FSSG, Meyer’s proposal enhanced rapid deployment, combat readiness, unit cohesion, training, and redundancy.

In 1992 Maj William S. Aitken wrote a prophetic thesis entitled “Increase the Size of the FSSG: An Evolutionary Idea.”8 At a time when the Marine Corps was beginning its force reductions, he stated that:

… current plans for the draw-down envision combining many of the battalions within the FSSG. By mixing the functions of combat service support, the FSSG will have trouble rapidly responding to contingencies.

He went on to state that in the fast-paced expeditionary operations of the future:

… units will need to be prepared and organized for deployment in a manner that lends to rapid mission accomplishment … there will not be time for reshuffling of staffs and troops and commands.

Opponents to restructuring the FSSG often point to the Gulf War as an example of its flexibility.9 CSS accomplished its mission in Southwest Asia, but the Gulf War is a poor historical case to justify the status quo. First, CSS had 6 months of preparation to work through the chaos of deployment and reorganization before ground combat occurred. The United States can no longer depend on the long periods of preparation that its global location in North America has afforded it in the past. In order to support the fast-paced expeditionary operations of the 21st century, CSS should organize before deployment becomes necessary. Second, the Gulf War exemplified the United States’ ability to overwhelm the enemy with its massive logistical might. With the drawbacks in manpower, material, amphibious shipping and, especially, airlift, CSS needs to become more proficient which requires innovative changes to the FSSG’s decades-old design.

In the May 2001 issue of the Marine Corps Gazette Col Thomas X. Hammes released the results of a symposium that discussed the lessons learned in the Gulf War.10 In spite of the Marine Corps Association’s commendable efforts to convene the seminar, many of the conclusions in regard to CSS and the FSSG appear understated or misunderstood. Although the conference recognized that the FSSG was not adequately prepared to provide operational CSS in the Gulf War, it appears to have accepted that these problems have been resolved through the creation of a notional Marine Logistics Command (MLC) in contingency plans. In reality, the MLC is an untested and untrained ghost. Even Col Hammes expressed some doubts in regard to the MLC, but a serious debate on the issue remains sorely lacking. In addition, the conclusion that the FSSG was, and still is, fully prepared for the tactical support of the MEF is questionable. The notional CSSDs in FSSG contingency plans are just as transparent as the MLC. In truth, the current organization of the FSSG supports neither operational nor tactical CSS but rather its peacetime responsibilities. Furthermore, the symposium faulted the FSSG for not fully understanding MPS but did not criticize its lack of proficiency in supporting large-scale operations. The reason why so much logistical effort was duplicated during the war had more to do with an FSSG that was not organized, prepared, or trained to employ in support of a MEF than with an ignorance of MPS.11 Unfortunately, these problems appear unresolved.

Training

In an April 2001 Gazette article by Capt Michael D. Grice entitled “Train Like We Fight,” Grice pointed out the many shortcomings of CSS training in support of CAX.12 However, he fails to mention that the deficiencies in CSS training primarily stem from the structure of the FSSG. With the short period of time allocated to a CSSD’s organizes tion, it takes a great deal of effort for the unit to support CAX, let alone participate in the training. For a newly organized CSSD, there are no such things as standing operating procedures (SOPs). Consequently, detailed plans must be made to accomplish nearly every task. And, Marines who are unfamiliar with each other must implement those details. CAX imparts beneficial experience to CSS personnel, but the CSSD loses most of that knowledge when the unit disbands. The next time a CSSD forms, lessons are learned the same way they were the year before-trial and error. The current system results in CSS units that support training exercises but rarely operate in accordance with the efficient performance required to win wars.

Assigning standing FSSG units to support exercises like CAX would provide a more thorough response to CSS and impart superior experience to the personnel assigned. A unit operates more proficiently when the personnel have a history together. High levels of loyalty, cooperation, and morale often characterize such organizations. A fixed unit can also incorporate the necessary changes to its SOPs so that the same mistakes do not occur year after year. Furthermore, the command and staff are readily familiar with their unit’s capabilities allowing CSS the time to fully participate with the air and ground elements during the planning process and throughout the exercise. Rotating a number of CSS units to support routine exercises creates a healthy spirit of competition. CSS could actually improve after each operation-the goal the FSSG should be striving for.

Culture

To quote MCDP-1, “Because war is a dash between opposing human wills, the human dimension is central in war.”13 When the basic philosophy, organization, and training of CSS fail to support maneuver warfare, cultural aspects are not far behind. For example, take a look at most FSSG battalions and prepare to be awed by the number of desktop computers. In fact, it is a rare occurrence to see a Marine using a laptop, and those that do usually make a considerable effort to attain one. The FSSG has neither the embarkation material nor the necessary lift to transport all those desktops. Even if transportation were available, shipping computers makes them unusable until after debarkation. Conversely, a laptop can be packed in a briefcase in less than 3 minutes, carried by its user via sea or air, and be ready for employment at a moment’s notice. Furthermore, the user is already familiar with the software required to perform the mission since it is the same computer that Marine uses daily. The FSSG should be using the platforms that are compatible with maneuver warfare, especially since doing so is cost-effective and takes little effort. The present preference toward desktops can be attributed to the fact that FSSG battalions are not organized for employment and rarely embark on large exercises. This creates an environment in which combat requirements become unanticipated.

A Solution

I believe the FSSGs should employ a handful of completely functional, yet flexible, CSS packages. One such configuration is illustrated in Figure 1. In this diagram, the FSSG is structured in accordance to its operational– level support, direct tactical support, and general tactical support functions. The General Support Command (GSC) concentrates on providing general support to all organizations within the MEF, while the Direct Support Command (DSC) trains and employs for the direct support of designated operations. I have labeled the four subordinate elements of the DSC by their more commonly known designation of CSSDs, but these units would actually be permanent. These CSSDs would have most of the inherent assets to support operations the size of a CAX or a MEU and could rotate to support both. However, the GSC could reinforce a CSSD to provide direct support to a special purpose MAGTF, or the DSC could employ multiple reinforced CSSDs to support a brigade or MEF forward. By maintaining a flexible infrastructure that can be easily reinforced, the CSSDs could support mobile, vertical lift, or landing support operations. In other words, the FSSG can task organize the direct support required for MAGTFs around the base units in the DSC. Ultimately, the standing organization of a DSC allows for the flexible, proficient, and speedy projection of CSS, which will more effectively support the Marine Corps’ expeditionary needs.

In essence I am suggesting that the FSSG create a handful of standing units similar to the MSSG. HQMC disbanded the standing MSSGs years ago, but the structure of the MSSG remains basically the same today. The MSSG can be viewed as a standing FSSG battalion that has been designed for a tactical purpose. (It simply has a 1 1/2-year tour of duty and a borrowed T/E.) What makes the MSSG operationally proficient is the time allowed for personnel to train together before deployment. The MSSG’s organization also permits sailors and Marines to conduct adequate turnovers with incoming personnel. Additionally, the equipment necessary to perform the MSSG’s mission has been correctly identified through years of operational experience.

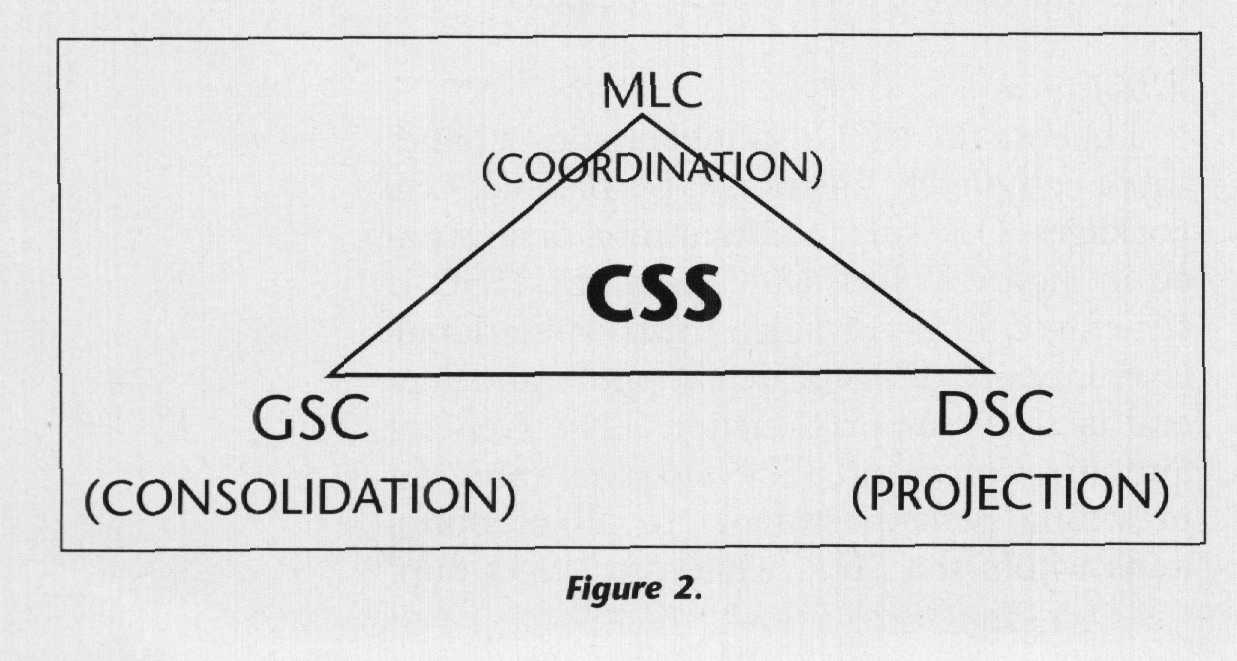

Equally important, the creation of an intermediary command between the FSSG and its battalions, as illustrated by the GSC, is long overdue. As a consequence of centralization, group headquarters directly supervises a number of CSS capabilities (consolidated personnel administration, consolidated food services, and numerous others). These additional tasks force the commanding general’s staff to focus inward instead of outward. At the operational level of logistics, resources need to be coordinated with our sister Services, the Department of Defense, civilian agencies, and host nations. The deficiencies in training and planning for these operational-level requirements were recognized as early as 1990 and still remain in doubt.14 By giving the FSSG organizational depth, CSS efforts can be distributed along the lines of Figure 2; in terms of a boxing analogy, MLC is the brain, DSC is the jab, and GSC is the power punch. By reorganizing in this fashion, group headquarters can better synchronize operational-level logistics in support of the MEF instead of expending precious energy micromanaging all of its CSS assets.

The proposed organization in Figure 1 is not all that original. It has many similarities to FSSG contingency plans as well as the structure of the FSSG during the Gulf War.15 Just as in the division and air wing, any organization of the FSSG must remain flexible. But, by establishing operating forces now, the FSSG can assign mission orders to standing subordinate units in time of war. If shortfalls are identified in the DSC, a general support unit can simply reinforce the deploying unit. If shortfalls exist in general support units, they can be filled by Reserves. This process allows the basic organization of the FSSG to remain intact upon employment.

Organizing the FSSG for rapid employment allows for genuine task organization in larger-than-MEU-sized operations. Should a contingency need several CSSDs, the DSC can quickly be augmented with additional CSSDs from other FSSGs. Or, one MLC could employ two, or maybe even three, DSCs. The point to be made here is that it is possible to establish the command, personnel relationships, and infrastructure that will support all five types of MAGTFs without recreating an entirely new FSSG every time wartime employment becomes necessary. For all intents and purposes, establishing an administrative organization that is designed for task organized employment makes for more thorough combat preparation, which is why most of the Marine Corps already operates in this decentralized manner.

Beyond aspects of organization, CSS needs a doctrine and culture that aligns with maneuver warfare philosophy. The FSSG must embrace decentralized decisionmaking and initiative-based mission orders rather than detailed and centralized planning. CSS units should annually conduct both large- and small-scale training exercises in an aggressive, realistic, and time-competitive environment. Furthermore, units should train in a manner that supports their combat employment, which means programs like combat skills training need to be eliminated or seriously adjusted. In short, the importance placed on preparing for war should take precedence over the routine and demanding tasks of garrison.

Impact on Force Structure

Forecasting the impact of FSSG’s reorganization on force structure is difficult. To begin with, I am not convinced that the solution presented is the only-or the best-one. Additionally, FSSG has reorganized under the constraints of manpower limitations and garrison requirements for far too long, which produced many of the current deficiencies. Instead, FSSG needs to create a completely revised T/O and T/E in accordance with a detailed examination of its wartime requirements. That task should be patiently and thoroughly completed before looking at the impacts on force structure, which may be significant or may be negligible. With a renewed brigade emphasis, perhaps the FSSG should review Carlton W. Meyer’s 1991 proposal. Conversely, Figure 1 depicts a flexible model that basically realigns existing units and current resources instead of creating original ones.

Although the purpose of this article is to stimulate the perception of the need to change, I will generally outline the force structure issues one could expect in a proposal along the lines of Figure 1. In this example the GSC is the only novel unit proposed. Basically, creation of this intermediate unit requires a reshuffling of the staffs in headquarters and service battalion and group headquarters. Although some new staff-level positions will need filling, I believe much of the GSC’s personnel could derive from group headquarters since the MLC would no longer need to manage all of its battalions.

As far as four permanent MSSG-type units are concerned, I have made the assumption that three CSSDs of the DSC could be made permanent based on the current manpower levels of the FSSG. Today’s MSSGs (equaling roughly 300 Marines each) are “temporary” organizations. Making them permanent implies that the FSSG’s battalions would lose roughly 900 line numbers on their T/Os. That may seem awfully hard to swallow, but the battalions already operate without these personnel on a daily basis. Those battalion line numbers considered essential for combat employment, but not necessary in garrison, could be filled by Reserves. Optimally, FSSG battalions could place entire platoons or companies in this reserve status, which preserves unit integrity.

The fourth CSSD proposed in Figure 1 provides the DSC with the flexibility to support the MEU as well as other CSS operations simultaneously, but it may require as many as 300 new line numbers. Combining the needs of 1st and 2d FSSG totals 600 additional Marines. Where will those Marines come from? Either the Corps can increase its size by 600 (which may be possible in today’s political climate), or (as blasphemous as it may sound) the air and ground forces could be reduced by a small fraction. The question that begs answering: does the Marine Corps want to be relegated to MEU-sized operations in the future, or do we desire the ability to rapidly respond in support of larger contingencies? In a Corps of over 150,000, increasing the manpower of the FSSGs by 600 Marines seems a small price to pay for flexible, proficient, and speedy CSS projection.

Summary

Currently, the FSSG is continuing to consolidate resources into MOS-specific units from which personnel and equipment can be reorganized to fit wartime situations. But, micromanaging the numerous CSS assets from FSSG headquarters is simply too large a task to accomplish effectively. The fixation with finding the exact requirements for any given operation wastes valuable time and, because of the nature of war, is unattainable anyway. The time required to create a perfect plan is exactly what the Marine Corps is attempting to avoid with maneuver warfare. Moreover, establishing peacetime garrison battalions that do not properly coincide with combat employment is precarious. The most dangerous aspect is that FSSG’s wartime requirements may not be correctly identified. Moreover, quickly organizing untested units defeats the benefits of training Marines in peacetime like they will fight in war. By establishing battalions that cannot be employed as they are organized, a “garrison-mentality” permeates the culture of the FSSG.

Recognizing the need to improve CSS is relatively easy, but implementing a solution will take strong leadership, force of will, collective cooperation, and patience. The Marine Corps is fond of using cliches like “. . . professionals think logistics” and “. . . logisticians win wars.” If the Corps adheres to its jargon, then it needs to take a second look at where the evolution of CSS is leading and ensure that it corresponds with maneuver warfare philosophy. If the FSSG cannot rapidly and efficiently employ in direct support of all five types of MAGTFs, then how can CSS effectively sustain the maneuver warfare doctrine being implemented by the air and ground forces?

Notes

1. For a historical perspective on the United States’ logistical changes, see Clayton R. Newell, “Logistical Art,” Parameters, March 1989, pp. 32-40.

2. For more information on the requirements for task organization, see Fleet Marine Force Manual 3-1, Command and Staff Action.

3. Renowned veteran Erick Von Schell stated that the German Army transferred many of its officers to new positions when WWI broke out. Schell believed this to be a mistake and maintained that “the heavy burden occasioned by the new impressions of battle would have been considerably lessened had there existed that feeling of unity and that mutual understanding which long service together engenders among officers and men.” Erick Von Schell, Battle Leadership, (Fort Benning, GA: The Benning Herald, 1933), pp. 20-21. For an outstanding review of the lessons learned while planning for the Guadalcanal operation, see Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal, (New York: Random House, 1990).

4. See MCDP-1, pp. 61-65. William S. Aitken discusses the necessity of personal relationships for proper CSS performance in his thesis “Increase the Size of the FSSG: An Evolutionary Idea,” Individual Research Paper, Marine Corps University, 1992, pp. 13-15.

5. MCDP-1, p. 55.

6. The need to organize CSS for rapid deployment while maintaining flexible employment has been recognized in the Army as well. See Leon E. Salomon and Harold Bankirer, “Total Army CSS: Providing the Means for Victory,” Military Review, 11 April 1991, pp. 3-8; or Wayne C. Agness and others, “Task Organizing CSS,” Infantry, September-October 1992, pp. 40-42.

7. Carlton W. Meyer’s idea was not unique; he borrowed it from a 1984 2d FSSG study. For Meyer’s proposal, see “The FSSG Dinosaurs,” Marine Corps Gazette, October 1991, pp. 32-36.

8. Aitken, William S., “Increase the Size of the FSSG: An Evolutionary Idea,” Individual Research Paper, Marine Corps University, 1992, pp. 1, 5-6.

9. Woodhead, John A., Col, “Reorganization of the Force Service Support Group,” Marine Corps Gazette, October 1991, pp. 37-38.

10. Hammes, Thomas X., Col, “DESERT SHIELD/DEsERT SToRm-Ten Years Later,” Marine Corps Gazette, May 2001, pp. 73-79.

11. Aitken, p. 12.

12. Grice, Michael D., “Train Like We Fight,” Marine Corps Gazette, April 2001, pp. 49-50. The problem of not integrating CSS into the training and evaluation portion of exercises occurs frequently. For an Army perspective, see Calvin R. Sayles, “Are We Ready: Combat Service Support Integration,” Armor, May June 1990, pp. 33-36. Also see Gilbert S. Harper and Robert J. Ross, “Managing CSS Unit Training,” Army Logistician, January-February 1990, pp. 6-10.

13. MCDP-1, p. 13.

14. For more information on how CSS could prepare for its theater-level responsibilities, see Jerome P. McGovern, “Combat Service Support at the High End of the Spectrum,” Marine Corps Gazette, January 1990, pp. 50-52.

15. O’Donovan, John A., “Combat Service Support During DEsERT SHIELD and DEsERT SToRm: From Kibrit to Kuwait,” Marine Corps Gazette, October 1991, pp. 26-31.