On to Richmond

By: Frank H. RentfrowPosted on February 15, 2025

Editor’s note: This story originally appeared in the January 1939 issue of Leatherneck Magazine.

It was a hot July day in 1862. Aboard the battle-wrecked Galena, the Marine Guard stood at attention. Bugles shrilled their flourishes, and the cheers of the soldiers at Harrison’s Landing could be heard above the brazen notes. The seamen froze in rigid blue ranks.

But there were great gaps in the formation, for, less than two months ago, Rebel shore batteries had swept away nearly half of the crew. Forty percent casualties in a four-hour fight! That ordeal was indelibly stamped on the faces of the survivors lined up to welcome the visiting dignitaries aboard.

Apart from the others were three men. Corporal John Mackie, commanding the Marine guard, stood flanked by two seamen. He stiffened perceptibly, with flushed face and eyes glinting with pride. A tall, gaunt man stepped away from the visitors and extended his hand to the Marine corporal. They smiled.

The rest of the visitors were smiling too. Admiral Louis Goldsborough positively beamed. His lost gunboats had been found. He had been worried about those four ships inconceivably swallowed up in the narrow confines of the James River. No one seemed to know where they were—except the enemy.

The Battle of Drewry’s Bluff

“On to Richmond!’” was the cry of the North. And General George McClellan, to appease it, maneuvered his army like pawns on the chessboard of war. Now he was ready to strike at the Confederate capital. Goldsborough dispatched ships from Hampton Roads to assist the troops and to open the James River for the passage of supplies. In response to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles’ orders to “push all the boats you can spare up James River, even to Richmond,” Galena, Port Royal, Aroostook, and Naugatuck cleared Hampton Roads—and then vanished.

The disappearance of the ships caused sleepless nights. The Navy Department wanted to know where they were, and Goldsborough, replying on May 13, reported that they had been last heard from on the 11th, somewhere in James River, about 25 miles from City Point. McClellan was apprehensive too, for he depended on those warships to aid him.

On May 15, he wrote to the Secretary of War to say, “I have heard nothing of the James River gunboats.” But on the following day he added, “A contraband just in reports that he heard an officer of the Confederate Army say our gunboats had reached within 8 miles of Richmond.” So, apparently, they weren’t lost at all. The Confederates knew where they were.

It is not surprising that the Confederates did know, for the Yankee guns had blasted Rebel river fortifications into silence. Aboard Galena, Mackie and his dozen men were kept busy, engaging the Confederate sharpshooters in a moving rifle duel. Every foot of the fleet’s progress was contested. Arriving at City Point, they found the place burned and abandoned by the defenders.

On May 13, the gallant little Monitor joined the other ships, and the flotilla continued up the James. The banks began pressing in on them as the river grew narrower, and as Mackie afterwards said, “crooked as a ram’s horn, with very high banks, heavily wooded on both sides, from which the fleet was constantly being fired on by Confederate sharpshooters hidden in the underbrush.”

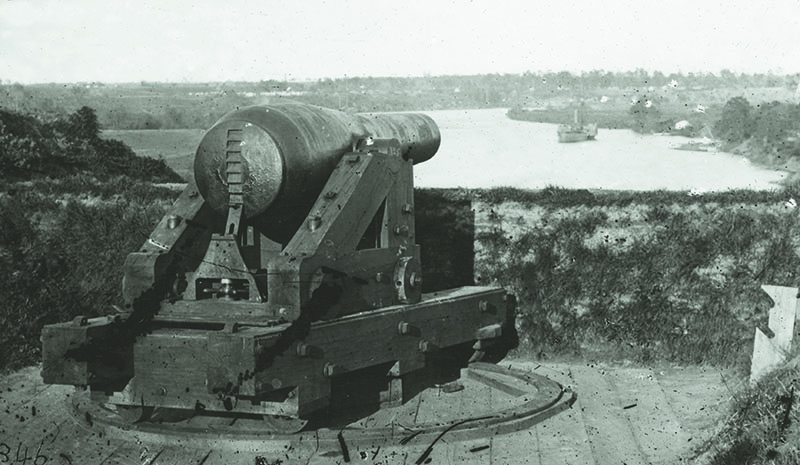

About 8 miles below Richmond their progress was halted abruptly by sunken ships and submerged piles. The obstructions could not be cleared, for on Drewry’s Bluff a battery of 10 guns frowned down to command the situation. There was nothing to do but fight; so the ships formed for action. They were in single line, with Galena leading and only 100 yards from the fort. The Marines were engaged in sniping at gunners even before Captain John Rodgers gave the command to fire.

Galena opened first, but her guns couldn’t be raised sufficiently. It would have required an elevation of nearly 35 degrees to reach the Rebel batteries almost above them. Then the Confederate guns went into action and the plunging fire just about blasted the ships out of the water. The fleet dropped back to an effective range and anchored.

Then the fight began in earnest. It was the final defense before Richmond, and the gray-clad gunners had been ordered to stick to the last man. All guns that could be brought to bear were in action and the battle raged in wild fury. The fire from the fort began to weaken. But Monitor had already fallen back, and the unarmored Yankee ships were badly smashed and in danger of destruction. So they moved about 1,000 yards down the river and left Galena to engage the enemy practically alone.

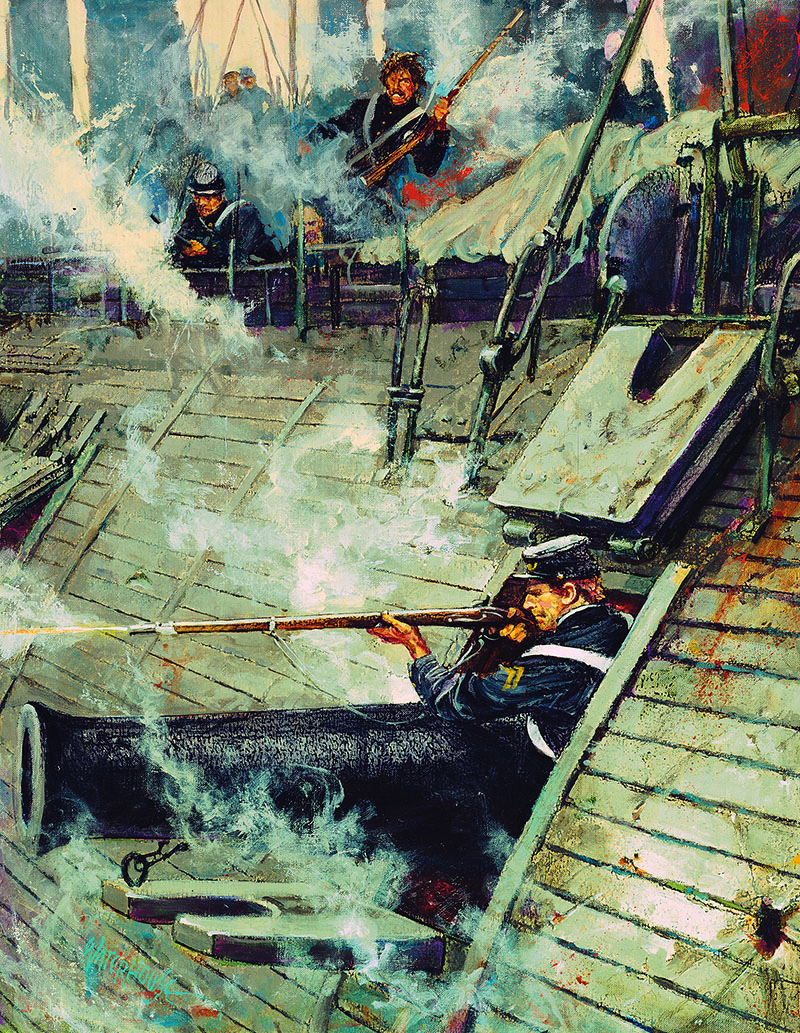

Suddenly, the Rebel fire increased and more riflemen appeared on the parapets. The crew from the Confederate ironclad Merrimac had been rushed down from Richmond to reinforce the Rebel strong point. The cannonading increased into a nightmare of violence. Galena shivered under the impact. Her six boats were smashed, and her stack resembled some strange, fantastic sieve. Great holes gaped in her sides, and her red, slippery decks were littered with broken spars and timbers. A shot struck the quarter-deck wheel, and it disappeared in an eruption of splinters.

A gunner raced up from the magazine and breathlessly reported to Rodgers that only five rounds of fixed ammunition remained. “Send it up as long as it will last,” replied the captain, “and then we will use solid shot.”

“Aye, aye, sir! snapped the gunner. He started to return below. An 8-inch shot screamed down and tore him to pieces. Four other men were killed and several wounded by the same projectile. Scarcely had its echo died away when a shell exploded on the deck in the midst of a group of men. A powder monkey in the act of passing a shell was hit and the thing went off in his hands. Long afterward, when the red horror had lifted from his memory, Mackie said: “Twelve men of the Marine Guard under my command and I were at the ports, taking care of sharpshooters on the opposite bank, and I barely escaped being struck by a 10-inch shot.”

“As soon as the smoke cleared away a terrible sight was revealed to my eyes: the entire after division was down and the deck covered with dead and dying men. Without losing a moment, however, I called out to the men that here was a chance for them, ordering them to clear away the dead and wounded and get the guns in shape. Splinters were swept from the guns, and sand thrown on the deck, which was slippery with human blood, and in an instant the heavy 100-pounder Parrot rifle and two 9-inch Dahlgren guns were ready and at work upon the fort. Our first shot blew up one of the casemates and dismounted one of the guns that had been destroying the ship.”

With Galena splintering about them, those Marines fought their guns like maniacs. A hostile shell ripped through into the boiler room. Another set fire to the ship, and the crew stamped out the blaze amid a torrent of shells. Finally, after four hours of combat, Rodgers realized he could not force past the Rebel batteries. So Galena limped out of range.

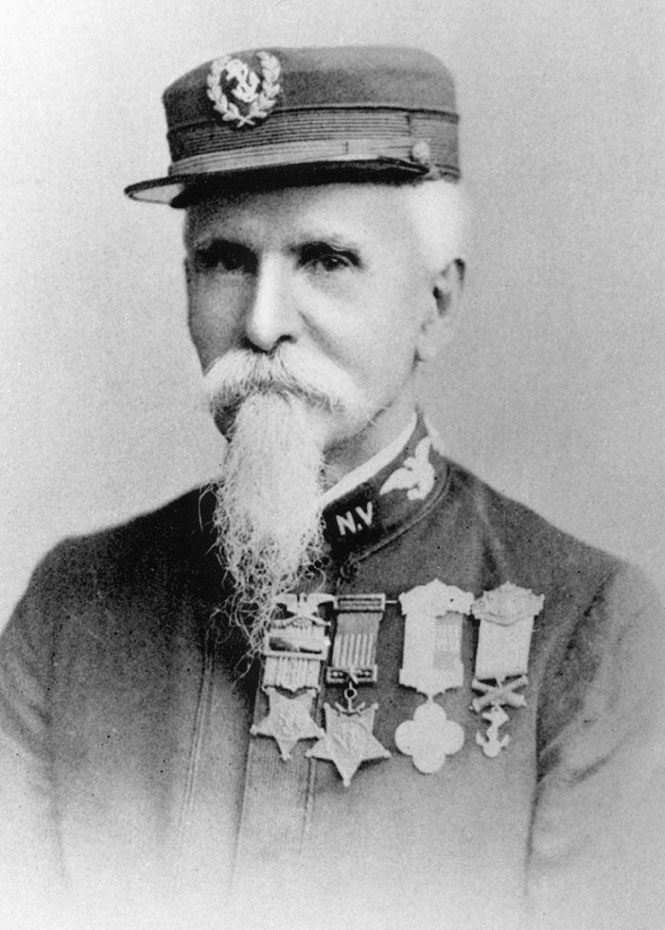

Torn from stem to stern, with 132 holes in her; with her port guns shored up to keep them from tumbling into the coal bunkers, the gallant little ironclad withdrew. Such bravery could not go unrecognized. That is why, two months later, a group of dignitaries climbed aboard and were amazed that Galena still floated. That is why Mackie stood between Quartermaster Jeremiah Regan and Fireman Charles Kenyon, outstanding heroes of the day, to receive credit for his bravery. Welles was there, and Admiral Goldsborough; Rodgers and the tall, gaunt, weary looking man who held out his hand toward Mackie.

“These, Mr. President,” said Rodgers, “are the young heroes of the battle.”

The tired eyes of President Abraham Lincoln smiled as he shook the hand of each man. Then he turned to Welles and directed that all three were to be awarded the Medal of Honor. This instance is probably the only time a president of the United States personally, and upon his own initiative, recommended the bestowal of this decoration.

A signal honor indeed! And for Mackie, it was a double honor for he became the first United States Marine ever to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

Of such threads is the web of destiny woven.