The Eminently Qualified Marine

By: Maj Shane F. HalpernPosted on October 24,2024

Article Date 22/10/2024

2024 Chase Prize Essay Contest Winner: Second Place

A satire of and recommendation for the Marine Corps Fitness Report

“A collection of talented individuals without personal discipline will ultimately and inevitably fail. Character triumphs over talent.” 1

—James Kerr, Legacy

“The nation that will insist upon drawing a broad line of demarcation between the fighting man and the thinking man is liable to find its fighting done by fools and its thinking by cowards.” 2

—Sir William F. Butler

Part 1: The Problem, in Satire

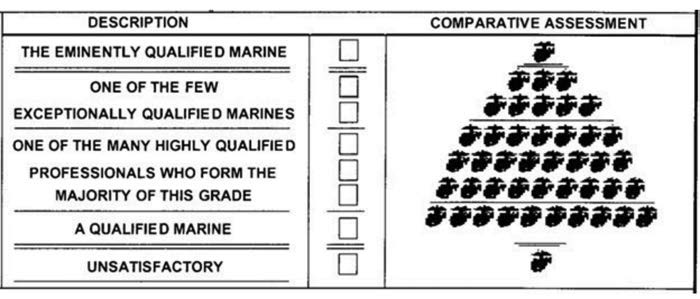

There is a pyramid of Eagle, Globe, and Anchor logos that comprise the Comparative Assessment Chart in Section K of the Marine Corps fitness report. The image is colloquially referred to as “the Christmas tree” for the diagram’s resemblance to the traditional holiday pine. In this portion of the report, a higher-ranking officer, who may not know the Marine very well, will compare the Marine’s value against that of other Marines who the higher-ranking officer also may not know very well.

At the bottom of the chart is a single logo, mimicking the stump of the tree, where the Corps’ invalids are lumped under the solitary, shameful tag of Unsatisfactory. Those who happen to blunder and slip through the cracks of bare proficiency to rank so lowly against their peers should be separated by a bold double black line to annotate inadequacy and disgrace.

Above the doomed are the Qualified, who represent the lowest trim of branches that merit holding ornaments. They are the foundational layer of bottom-third talent upon whom those of higher standing rely to buffer against shame. To be qualified is to be relegated to an inference of sub-standard functioning that, while technically satisfactory, must be categorically subjugated and cataloged as a group that has failed. They only did what they were told to do.

Then, atop the regular folk but just below la crème, sit the masses of the Many Highly Qualified Professionals Who Form the Majority of this Grade. It is quite the epithet, especially considering the phrase portends where most Marines shall be assessed. They have done much more than is to be expected and should think highly of their accomplishments. However, that they have done more that what is expected of Marines. They will find a modicum of success within the organization.

Next, one finds the proverbial pick of the litter, also known as One of the Few Exceptionally Qualified Marines. These must be the men and women who are charged with keeping bright the shining light atop the Corps’ hill because, without their influence, how will those wide-eyed followers beneath them know the morally right from the objectively wrong? When young boys and girls say out loud to their friends at recess that they want to grow up to be a Marine, this is what they intend.

Still, there is a rank above these do-no-wrongers. At the top of the Christmas tree is another single Eagle, Globe, and Anchor logo. This one is labeled: The Eminently Qualified Marine. It is commonly understood that no Marine truly ranks in this category. It exists to humble us and to let us know that only because the very best of our ancestors were so exceedingly proficient at winning wars was this classification even created.

However, this is not the system that describes human interaction. The pursuit of principled achievement cannot be summed through an exaggerated appellation that has no real definable metric. Who has not woken up on days and felt barely Qualified? Yet, there is no box to tick for One of the Many Who Succeeds in the Daily Conquering of an Inner Demon. Nor is there a category for Unassuming, Yet Expertly Competent. Who is not eminently qualified, sometimes, though having made unsatisfactory errors in judgment and execution, on occasion?

Nonetheless, the slow, steep climb out of despair starts with one trudging step in darkness. Arguably, this is the hardest step. Marines might better be judged by how far and determined their trek than if they were able to plant a flag on the summit of eminence. The latter is an evaluation of talent; the former is an assessment of character.

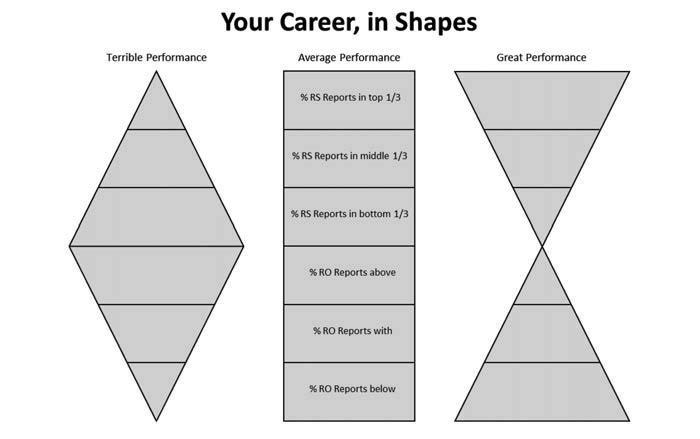

As leaders commonly convey, Marines are promoted on future potential rather than past performance. Yet, the current version of the Marine Corps fitness report does little to characterize the potential of individuals. In fact, its sole function is to quantify past performance. The report and its accompanying master brief sheet codify every blemish, categorize every remark, and collate every meritorious phrase, reducing the sum of evaluations into a single comparative number known as a relative value. These values form the proverbial hourglass figure (or lack thereof): the graphical depiction of a career’s worth of reports.

The obvious discrepancy when attempting to shape-ify performance over the length of a career is the lack of nuance regarding the individual. Fitness reports capture performance for instance, and master brief sheets average those instances across a decade or more. Neither provides an evaluation of potential, which, at least colloquially, is the fundamental attribute for promotion (and by implication, denotes character). To avoid propagating the Peter Principle, where Marines rise to their level of incompetence, we must select for potential, within which is an assessment of character, and prepare prospective promotables for future successes.3

Part 2: Selecting for Potential (and by Implication, Character)

The first part of this recommendation, and an easy proposal to make, is an update to the evaluation form. The problem, however, is defining potential. Then, once defined, quantifying it for comparative review. For the former issue, Harvard Business Review identified three general markers of high potential: ability, social skills, and drive.4

At its core, the current fitness report is an appraisal of ability. Essentially, the report is a drawn-out work sample test, where Marines are evaluated based on observations of the tasks that make up their job. That this evaluation is divided into five sections and fourteen sub-sections simply demonstrates the extent to which the individual’s ability (in his current position) is scrutinized. However, when evaluating a candidate for a higher, more complicated position, the capacity to learn “where the single best predictor is […] cognitive ability”5 supersedes the propensity to perform. In this sense, a premium should be placed on education, the ability to acquire new skills quickly, and flexibility in new roles or when making mistakes. Still, beyond a measure of raw cognitive ability, promotion to each successive rank or position requires examination of intangible items related to intelligence. As an example, promotion to a rank of organizational influence or selection for leadership positions should include an assessment for creativity and a knack for systems thinking.6 These advancements should also involve a sense of vision and imagination, items not usually captured in a standard annual report. Moreover, if the Corps is serious about promoting smart Marines, then the organization should test for aptitude as a required element of promotion, command, or school selection. Evaluation of ability, as it relates to potential, requires a rigorous assessment of intelligence.

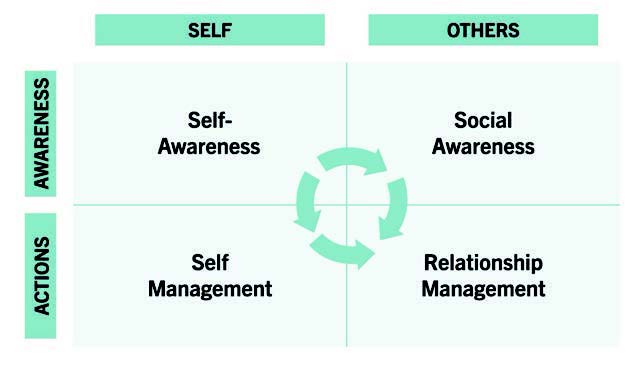

Social skills are the core elements of emotional intelligence, another item not explicitly measured when concerning retention, promotion, and selection for advanced programs or leadership opportunities. The core competencies of emotional intelligence, depicted with their relationships in Figure 3, are self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management. The primary attribute, self-awareness, describes the ability to understand your own strengths and weaknesses and recognize how they impact the team’s performance.7 Related, and perhaps the one item mentioned within the current Marine Corps fitness report, addressed as effectiveness under stress, is self-management. Beyond basic recognition, self-management refers to the ability to manage emotions, especially under stressful conditions. Social awareness closely relates to empathy and can best be described as knowing how to read a room. Lastly, relationship management “refers to your ability to influence, coach, and mentor others, and resolve conflict effectively.”8 The evaluation of these social skills, progressing generally in order of merit as they are listed above, is necessary to qualify emotional intelligence, an important factor in determining potential and assessing character.

An individual’s drive, best expressed in the current fitness report as initiative, is probably the most measurable and the most easily shaped by the environment. To the latter point, and in the parlance of the expectancy-value theory, drive is “motivated by a combination of people’s expectations for success and subjective task value in particular domains.”9 To this end, a Marine’s drive partially belongs to the individual yet is also indicative of a leader’s ability to create expectations of success and valency of the tasks to lead to it.

Part 3: Evaluating through Education

If cognitive ability is the single best predictor for higher-level success within the organization, then a Service-level investment in an individual’s intellect is the best groundwork for collectively preparing cohorts of Marines for selection and promotion. Furthermore, the results of that educational assessment (e.g., class ranking) should inform competitiveness for future opportunities. Within the officer corps, career-level, intermediate-level, and top-level schools require professional military education (PME) for promotion to the respective ranks of major, lieutenant colonel, and colonel. Whether accomplished through resident PME (an allegedly selective process for attendance) or through non-resident education, and irrespective of the Marine’s relative success at the school, accomplishing PME is briefed at non-statutory boards as either complete or incomplete.

While the Marine Corps PME system excels in providing a baseline education to the masses, at least for the officer ranks, it lacks a tool for educational assessment that could advise promotion and selection panels on the potential of a Marine for advancement or command. If resident PME is truly selective, then attending an in-person school program is the first aimpoint for an individual’s efforts to increase his or her value to the organization. It then follows that Marines are incentivized to perform well if they understand that the educational assessment affects career potential.

Beyond baseline educational schools, such as Expeditionary Warfighting School for captains or Command and Staff College for majors, specialty schools aligned to billet or general job descriptions are few and far between. If an infantry captain attends the Army’s Maneuver Captain Career Course (MCCC), then he is well-prepared to be an infantry company commander. Conversely, if the same captain attends Expeditionary Warfighting School, he or she is well prepared to be a staff officer in a MEU. Why is a curriculum like MCCC not mandated for the preparation of incoming company commanders? Why does the student’s evaluation from a school like MCCC not influence whether he or she should be a company commander? These schools, and many like them, become proverbial checks in boxes without any measurable bearing on a Marine’s career.

Part 4: A Recommendation

Character and intelligence ebb and flow over the course of a career, ideally upward, yet the fitness report and the master brief sheet do little to distinguish progress. Evaluations must be adjusted to provide the best picture of the current Marine’s value. Only the last five observed reports should be included in the master brief sheet.

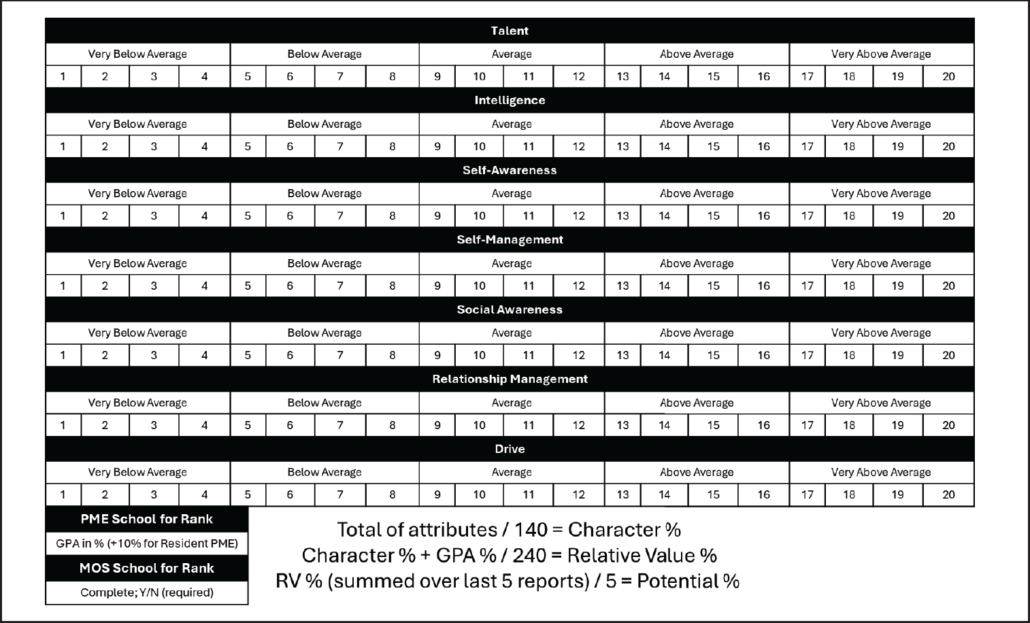

If a fitness report is a tool used to screen promotion and selection opportunities, then its sections must evaluate potential. These sections should include ability (identified as talent and intelligence), social skills (identified as self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management), and initiative (i.e., drive).

If cognitive ability is the single best predictor for higher-level success, then resident education should be valued higher than non-resident, and the individual’s evaluation at a PME school should affect master brief sheet percentages. Additionally, skill-enhancing schools should become a requirement for advancement within military occupation specialty fields.

Figure 4 is imperfect and requires a process for normalization within a reporting senior’s profile. Additionally, it does not address the reviewing officer’s markings—but it does provide a better framework for how those markings should be applied. In any case, the current Marine Corps fitness report format is multiple decades old; it is time to accept a challenge to improve.

“The challenge is to always improve, to always get better, even when you are the best. Especially when you are the best.” 10

—James Kerr, Legacy

>Maj Halpern is an Infantry Officer whose previous experience includes deployments with the 22d MEU, FAST Deployment Programs, and SPMAGTF–Crisis Response Africa. Additionally, he spent two years working within the Australian Defence Force as part of the Marine Corps Personnel Exchange Program–Australia. Following, he served as the Assistant Operations Officer for 7th Mar. He is currently the Future Operations Officer for 4th Mar.

Notes

1. James Kerr, Legacy: What the All Blacks Can Teach Us About the Business of Life (London: Little, Brown Book Group Limited, 2013).

2. Sir William F. Butler, Charles George Gordon (London & New York: Macmillan & Co, 1893). Charles George Gordon served in the British Army from 1852–1885, retiring as a major general. He served in the Crimean War, the Second Opium War, the Taiping Rebellion, and the Mahdist War.

3. “Peter Principle is prevalent in situations where people downplay the aptitude for management when making promotion decisions in organizations. In most cases, promotion decisions are made largely dependent on current performance. Therefore, those who excel in their current roles are promoted to managers despite not having the necessary management skills.” Human Capital Hub, “Peter Principle: What You Need to Know,” Human Capital Hub, May 29, 2023, https://www.thehumancapitalhub.com/articles/peter-principle-what-you-need-to-know.

4. Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, Seymour Adler, and Robert B. Kaiser, “What Science Says about Identifying High-Potential Employees,” Harvard Business Review, October 3, 2017, https://hbr.org/2017/10/what-science-says-about-identifying-high-potential-employees.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Lauren Landry, “Emotional Intelligence in Leadership: Why It’s Important,” Business Insights Blog, April 3, 2019, https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/emotional-intelligence-in-leadership.

8. Ibid.

9. Robert V. Kail and Campbell Leaper, “Chapter 9-More Similarities than Differences in Contemporary Theories of Social Development: A plea for theory bridging,” in Advances in Child Development and Behavior 40 (Burlington: Elsevier Science, 2011).

10. James Kerr, Legacy: What the All Blacks Can Teach Us About the Business of Life (London: Little, Brown Book Group Limited, 2013).