Talent: We Do Not Need It

By: Maj Jeremy G. CarterPosted on October 24,2024

Article Date 22/10/2024

2024 Chase Prize Essay Contest Winner: First Place

Eleven challenges to Talent Management 2030

As stated in Talent Management 2030 (TM2030), “Our modern operational concepts and organizations cannot reach their full warfighting potential without a talent management system that recruits, develops, and retains the right Marines.”1 While this statement is extremely valid, there is one significant problem with this sentence, and furthermore, one significant problem with TM2030—specifically the word talent. Simply put, the Marine Corps does not need talent.

Talent Management 2030’s mandate is to “achieve a full transition from the current manpower system to a talent management system no later than 2025.”2 However, there are challenges that need to be addressed immediately to facilitate this intent to the fullest—increasing our combat lethality, operational effectiveness, and survivability to win our Nation’s battles. Therefore, this article poses eleven challenges to TM2030 and describes how the Marine Corps does not need talent. The ultimate thesis is that we do not need a talent management system but a Marine management system.

Challenge 1: Talent is Overvalued

In his book, Talent is Overrated, Geoff Colvin defines talent as: “A natural ability to do something better than most people can do it.”3 This is similar to how TM2030 defines talent (i.e., “an individual’s innate potential to do something well.)”4 Regarding talent being overvalued, throughout the book, Colvin’s research showcases that we exceedingly credit innate gifts (i.e., talents) to top performance. The reality is that top performance comes from extreme purposeful effort (i.e., deliberate practice).5 Colvin describes how we overinflate talent with musicians, intelligence, and individuals such as Tiger Woods and Mozart.6 In fact, Colvin’s book demonstrates that top-performing musicians practiced 800 percent more than lower-performing musicians and that both Tiger Woods and Mozart’s fathers started their training while they were infants and toddlers. Therefore, they could hardly be described as child prodigies.7

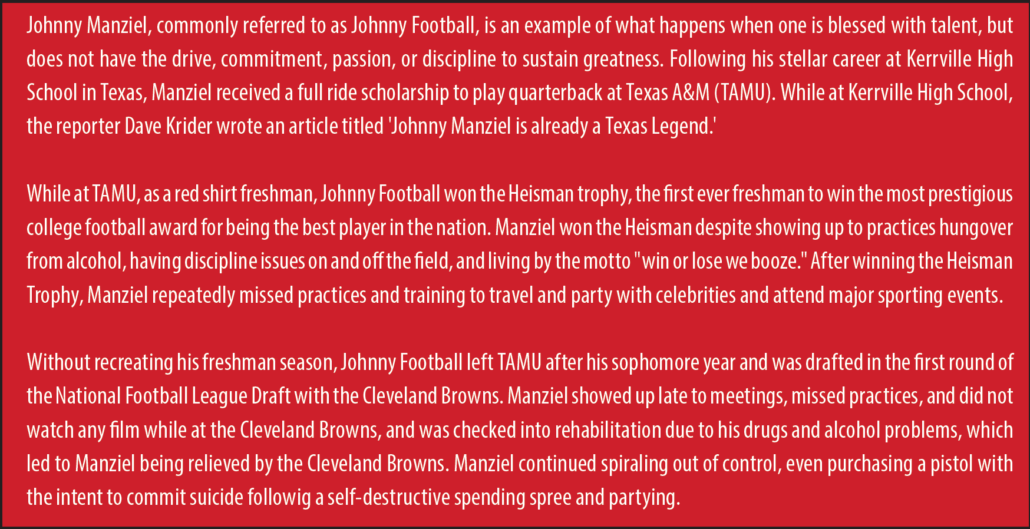

As seen in Case Study 1, Johnny Manziel shows that talent will only get a person so far in one’s career. Colvin credits high consistent performance with deliberate practice, not talent.8 “Deliberate practice is also not what most of us do when we think we’re practicing … Deliberate practice is hard. It hurts. But it works. More of it equals better performance. Tons of it equals great performance.”9 Deliberate practice can be summarized as practice that is purposefully designed to elicit performance by pushing a person just beyond their current limits, with high quality, frequent and recurrent repetitions, with immediate feedback, and is mentally taxing.

“… but of course we can take any credit for our talents, it is how we use them that counts.”

—A Wrinkle in Time

Challenge 2: Experience is Overinflated

When you read Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Outliers: The Story of Success, the reader will clearly see that talent, experience, or rank did not enable the outliers (top performers) to achieve greatness, rather it was the opportunity combined with hard, diligent work.10 Mike Eruzione, captain of the 1980 U.S. Miracle hockey team, credits two fortunate chances (i.e., opportunities) in his life that provided him the opportunity to score the winning goal on 22 February 1980 against the Soviets; however, it was Eruzione’s blue-collar work ethic that allowed him to exploit those chances.11 Regarding experience being overrated, as stated by Colvin, “extensive research in a wide range of fields shows that many people not only fail to become outstandingly good at what they do, no matter how many years they spend doing it, they frequently don’t even get any better than they were when they started.”12

Furthermore, Colvin states: “More experienced doctors reliably score lower on tests of medical knowledge than do less experienced doctors; general physicians also become less skilled over time at diagnosing heart sounds and X-rays. Auditors become less skilled at certain types of evaluations.”13 The way we should view experience is as whether or not one’s experience is that of a low performer, average performer, or a high performer. For too many in our Corps, our experience is that of being average; yet, we overinflate having experience of being average to that of credibility.

Let us never confuse a driven, hardworking, and problem-solving individual who possesses little experience to be less than an individual with more experience of being average. What we should acknowledge and reward is not experience but rather learning, innovation, effort, and the ability to fail and grow. Of note, “sub-elite skaters spent lots of time working on the jumps they could already do, while skaters at the highest levels spent more time on the jumps they couldn’t do.”14

Challenge 3: Rank is Overrated

As stated in TM2030, “We should have an open door for exceptionally talented Americans who wish to join the Marine Corps, allowing them to laterally enter at a rank appropriate to their education, experience, and ability.”15 However, anyone who has been in the Marine Corps long enough knows that rank is overrated. We have all seen the lance corporal who outperforms the sergeant; the sergeant who outperforms the gunnery sergeant; or the captain who outperforms the major. Similar to talent and experience, rank is overrated.

As stated by Evans Carlson when he was the 2d Marine Raider Battalion commanding officer in World War II, “Are you willing to starve and suffer and go without food and sleep? I promise you nothing but hardships and anger. When we go into battle, we ask no mercy, we give none.” We should ask a similar question for those qualified (not talented) individuals we are trying to recruit into our Corps, specifically are you willing to start at the bottom, earn the title U.S. Marine, give up the comforts of your life that you are accustomed to, so that you may serve alongside the finest men and women of the United States?

Gen Krulak stated on 6 May 1946 to the Senate Committee on Naval Affairs in his infamous bended knee speech:

Sentiment is not a valid consideration in determining questions of national security. We have pride in ourselves and in our past, but we do not rest our case on any presumed ground of gratitude owing us from the Nation. The bended knee is not a tradition of our Corps. If the Marine as a fighting man has not made a case for himself after 170 years of service, he must go.16

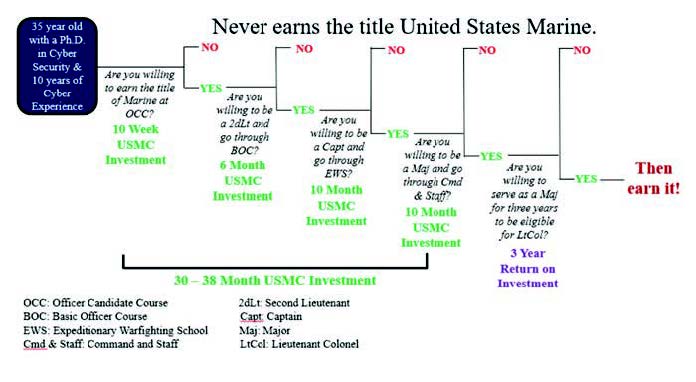

Then we must ask our Marine leaders of 2024, why do we have a bent knee to civilians with credentials we value? Figure 1 is a simple flow chart that displays if we as Marines should accept a 35-year-old with PhD in Cyber Security with ten years of cyber experience to try out for our Corps and earn the title of Marine. It has been stated that humility needs to be incorporated into our Marine culture, and if a civilian is not willing to humble himself, start at the bottom, and earn our title, then we do not need that individual.17 Of note, in the book Good to Great, Collins notes that “ten of eleven good-to-great CEOs came from inside the company, whereas the comparison companies tried outside CEOs six times more often.”18

Challenge 4: We Already Recruit a Different Person

As stated in TM230, “the core objectives of all modern personnel management systems are to recruit individuals with the right talents, match those talents to organizational needs, and incentivize the most talented and highly performing individuals to remain with the organization.”19 However, as emphasized, talent is overvalued. Furthermore, are we certain that TM2030 is truly appreciating what we should be recruiting? Case Study 2 showcases what happens when you recruit for the wrong variables, such as perceived talents.

Our history, culture, character, and standards should draw the correct Americans toward us. Coach John Wooden coached the University of California Los Angeles for 29 years, where he won 10 national championships, had 4 perfect seasons, and 88 consecutive victories. Over Wooden’s 29 years as a coach, he only visited 10–12 players at their home but only after the athlete initiated first contact. Coach Wooden’s philosophy was that if these high-performing athletes did not want to play for the University of California Los Angeles, then perhaps they should play somewhere else.20

As stated by Coach Wooden:

I always felt that my nonrecruiting policy for players was the right thing to do—a productive part of the screening process. Before I talked to an individual about joining us, I first wanted to see evidence of his desire to be a part of the Bruins. The last thing you want is people in your organization who had to be talked into being there, who needed convincing that your team was worthy of them … Recruiting should be a two-way street.21

Furthermore, as stated by Dave Nassef, “I used to be in the Marines, and the Marines get a lot of credit for building people’s values. But that is not the way it really works. The Marine Corps recruits people who share the corps values, then provides them with training required to accomplish the organizations mission.”22

While we need to improve our recruiting process, we need to recognize we are already recruiting a different American. What we do with that American, from their initial training until they get out of our Marine Corps, rests on our shoulders as leaders and commanders. Specifically, we must truly sustain the transformation; make our Marines more lethal, resilient, and proficient; and retain the right Marines. Lastly, our legacy and current culture should continue to drive the right (not talented) civilians to want to earn the title of Marine.

Challenge 5: Entry Training Needs to be a Selection Process

We do need to improve our recruiting process. However, we must also increase the standard of our entry-level schools (basic training [BT] and Officer Candidate Course [OCC]). As stated in TM2030, “approximately 20% of those recruited do not complete their first enlistment, a strong indicator that the service can do better to screen potential recruits.”23 While TM2030 states that we need to recruit to a higher standard, TM2030 completely negates the fact that the twenty percent who do not complete their first enlistment earned the title Marine. We failed our ancestors by allowing such a high number of individuals with the inability to serve four years in our Corps to earn the title of Marine.

Civilians wanting to earn the title of Marine are already volunteering to serve their country in the hardest Service. We should not forget this; we are already recruiting a different person. However, we need to take the earning of the title to a higher standard. We should treat BT and OCC the same way Marine Corps Special Operations Command treats assessment and selection. Specifically, BT and OCC should be a selection process. Based on the data, at least twenty percent of those who start BT should not earn the title of Marine.

Challenge 6: Talent Management Neglects Leadership

As stated in TM 2030, “A Marine turns their talents into strengths, aptitudes, and skills through dedicated study, repetition, and hard work—a process accelerated by their curiosity, passion, and interests, and desire for excellence.”24 This is similar to the sentiment in Training and Education 2030 that states, “ultimately, every Marine is responsible for their own learning.”25 However, it has been posed that while each Marine is responsible for their own learning, “We as leaders in the Marine Corps must recognize it is imperative to educate our Marines by providing the optimal resources and direction.”26

In a similar vein, while it is the Marine’s job to turn their talents into strengths, it is also a mandate of Marine leaders to get the most out of their Marines, to include improvements in their strengths and weaknesses, in their interests and non-interests. Leadership has been defined as, “The ability to inspire and influence those around you to perform at a higher level and become better versions of themselves.”27 A leader’s job is to push Marines. Grow them, push them outside their comfort zone, build interests, develop passion, create opportunities, make innovation occur, give feedback, create optimal experiences, and develop specific, detailed, and progressive training. The moment the Marine Corps ceases to make leaders, our Nation should divest of her. Therefore, we must make leadership a part TM2030.

Challenge 7: Leaders and Commanders Cannot Retain the Right Marines

A significant reason we have issues retaining the right (not talented) Marines in our formation is the direct leadership and command experienced by our young Marines during their short tenure in our Corps. Simply put, the Marine Corps did not lie to us—all one has to do is to look at our recruiting posters which typically either display a Marine in their dress blues or a Marine suffering in training. The Marine Corps promises civilians the ability to earn the title Marine (i.e., dress blues) as well as tough and miserable times via realistic training, physical conditioning, deployments, etc.

However, the Marine Corps also promises competent, moral, ethical, and beyond-reproach leaders. When we fail to deliver strong, competent, and confident leaders who possess humility, we lose the trust, passion, and motivation of our Marines we fail to sustain the transformation and retain the right (not talented) Marines.

Challenge 8: Our Culture (Not Talent) is What Makes Us the Marine Corps

As stated in TM2030, “Marines make the Marine Corps. We have never defined ourselves by our equipment, organization constructs, or operational concepts.”28 Furthermore, as stated by Gen Berger, “Our historical and legislatively mandated role as the Nation’s force-in-readiness remains a central requirement in the design of our future force. The most important element of this requirement is the individual Marine.”29

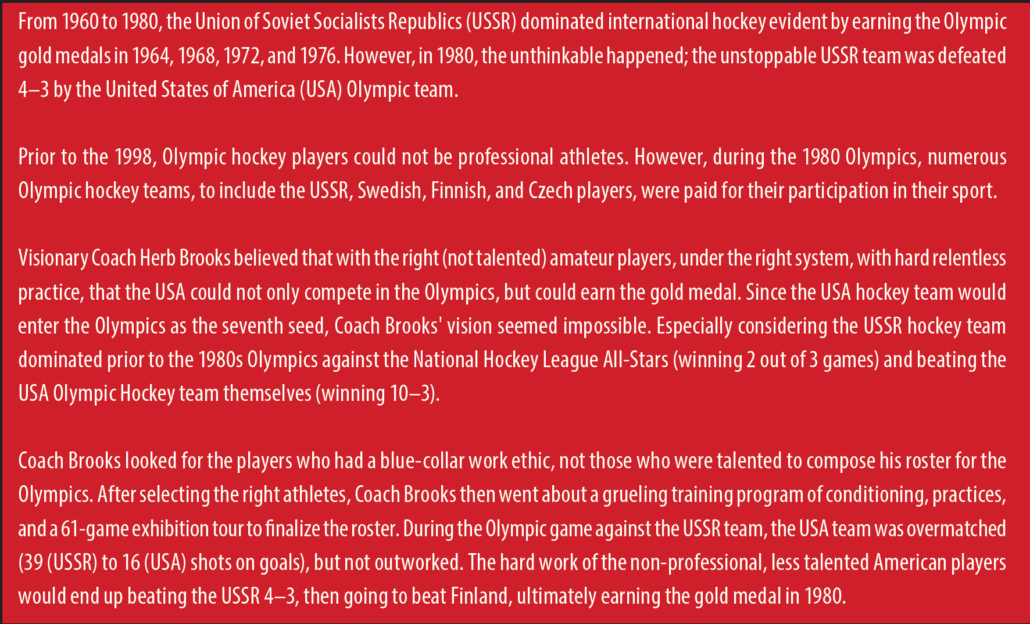

The title of Marine should not be synonymous with talent. If Marines are to be synonymous with talent, then we should divest of BT, the Crucible, OCC, basic officer course, etc. Marines should be synonymous with riflemen, learners, leaders, problem solvers, resilient, passionate, dedicated, winners, driven, disciplined, professionals, accountable, and reliable—not talented. Case Study 3 displays that purposeful effort can achieve greatness while lacking the talents needed.

In the book The Culture Code, Daniel Coyle states, “Our instincts have led us to focus on the wrong details. We focus on what we can see—individual skills. But individual skills are not what matters. What matters is the interaction.”30 As stated, the “Marine Corps culture is what makes us who we are. Our warfighting culture is what made us successful in battles past, and our culture will either enable or hinder our future battles. Remember, our culture is our DNA, and while we cannot see it, we see its manifestation, which for the Marines, is on the battlefield.”31

Challenge 9: Mandate a Culture of Pursuing Performance

Talent Management 2030 states, “Once an individual earns the title ‘Marine,’ they have made the grade. There are no additional obstacles or barriers to entry—‘Once a Marine, always a Marine,’” and that we must encourage a culture of inclusion.32 TM2030 additionally directs our leaders to “focus on building inclusive teams … based on performance.”33 There are two issues with this: the passivity of the word encourage, and the passivity and acceptance of simply earning the title of Marine is enough.

Regarding culture, I have argued “that the single greatest contributor to a high-performing unit is the unit’s culture.”34 Furthermore, we as leaders “must define, emphasize, measure, acknowledge, and correct the culture we pursue.”35 However, leaders and commanders, who are the owners of the unit’s culture, should not encourage (passive) our culture, we should mandate (active) the culture we pursue.”36 We should have a culture of “hostility towards mediocrity.”37

Second, we as Marines should be proud of the title Marine, but we should not be content with just the title. Our mothers can be proud that we once earned the title Marine; however, we must earn that title every day while in uniform. Having graduated from BT or OCC is not enough. Far too many Marines in our Corps peak at earning the title Marine, evident by the twenty percent unable to complete four years of service.38 While hazing, tribalism, and/or a culture of less than for being new to the Marine Corps is not warranted nor is it productive, there should be daily challenges and mini-goals. However, these daily challenges and mini-goals are completed by each Marine in the unit every day. These can be physical or cognitive events done individually or collectively. However, each Marine regardless of rank, billet, years of service, or MOS should earn the title every day. Being a Marine should be a holistic, deliberate lifestyle. Case Study 4 shows that even talent must pursue greatness.

Challenge 10: Define Performance

Talent Management 2030 discusses performance, but we as an organization have failed to define what performance means for early 21st-century warfighting performance (CWP). The more clearly defined a trait is, the more easily we can measure it. The better we can measure it, the more easily we can acknowledge success and correct setbacks. Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1 describes the constants of war via Chapter 1, The Nature of War.39 The changing character of the modern-day battlefield can be seen in the rise of private military contractors, the execution and planning of war by non-humans (i.e., drones and artificial intelligence), the saturation and proliferation of information and disinformation, additive manufacturing, and the accelerating pace of change.40

Without clearly defining early 21st-CWP, we will have: an unnecessary variance in preparation for war, a greater inherent risk of creating myopic definitions which leads to suboptimal performance, and increased risk by misclassifying performance, leading to incorrect emphases. Thus, we must adequately define early 21st-CWP. The author states that early 21st-CWP is the transient and relative capacity to impose our will during times of cooperation, competition, crisis, and conflict; the transient and relative capacity to efficiently and effectively achieve mission success criteria on the three levels of war; relative to the enemy, environment, and political situation, and a pursuit, where we never fully culminate. This definition of early 21st-CWP applies from the individual to the platoon to the Joint Force.

Challenge 11: Talent Management is the Incorrect Sentiment

While TM2030 has numerous valid points, the Marine Corps does not need talent. Those who do possess talents (i.e., innate abilities) can often achieve quick success in learning new skills. However, when these talented individuals do not combine their gifts with practice, passion, or by challenging themselves, they will be surpassed by those who are less talented but are driven. For our newest Marines to join our ranks, current performance does not directly reflect future performance.

For example, a talented infantryman who recently graduated from Infantry Training Battalion may be more physically fit, have greater cognition, and display what we might perceive as being a leader, compared to a peer lacking in those domains due to their talents. However, if this Marine does not have the drive to be a better infantryman, Marine, or leader, and if a less-talented Marine were to consistently and deliberately practice his deficiencies, then over time, the less-talented Marine would become the better infantryman. In the book, The Sports Gene, Epstein states that regarding becoming a high performer, the 10,000-hour rule is what the average person takes to become an expert with intentional and designed practice.41 However, David Epstein states that due to people’s innate abilities (talents), it should really be called the 10,000 ± 5,000 hours because some can become experts in 5,000 hours, whereas others will take 15,000 hours to become experts. Thus, a talented, low-driven Marine may never make the 5,000 hours needed to become an expert, but the less talented, high-driven Marine may very well accumulate 15,000 hours. A talented Marine with low drive will be the first to fall asleep on watch, the last to volunteer for extra duties, and will not embody esprit de corps. Therefore, we can see that talented Marines are not innately preferable to hard-working, driven Marines.

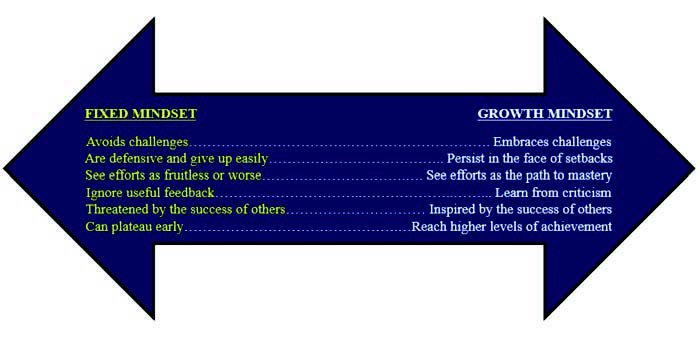

Furthermore, talented individuals can be less resilient to failures and setbacks. In her book Mindset, Dr. Dweck’s research shows that individuals who are praised for their talents can develop fixed mindsets.42 While those with fixed mindsets can be highly successful, they are ultimately less resilient than those with growth mindsets. Figure 2 summarizes the research by Dr. Dweck regarding those with fixed mindsets to those with a growth mindset.43

Therefore, talent management is not the right sentiment; rather, it is Marine management. While there would be significant overlap to the principles laid out in TM2030, Marine management recognizes that we should not emphasize innate gifts, but whether or not the Marine is making improvements in their MOS and billet and is living by the ethos we pursue. As stated by Coach Herb Brooks, coach of the 1980 U.S. Miracle hockey team, “Gentlemen, you don’t have enough talent to win on talent alone.”44

Conclusion

While there are eleven challenges to TM2030, there are many facets I fully agree with, such as: “Marines are individuals, not inventory,” “Talents can be identified and evaluated,” and “Data drives decision-making.”45 Furthermore, transforming our recruitment system as identified in TM2030 is vital moving forward as well as increasing opportunities for Marines while in uniform.46

As stated in TM2030, “It begins and ends with preparedness for combat. Our ability to fight and win on future battlefields demands a personnel system that can recruit, develop, and retain a corps of Marines that is more intelligent, physically fit, cognitively mature, and experienced.”47 Were the Marines at Belleau Wood, Iwo Jima, and the Chosin Reservoir able to impose their will on our enemies because of their talent (i.e., innate ability), or were our forefathers able to impose their will because they were Marines, forged in training, developed by small-unit leaders, led by morally-competent commanders, fighting for a purpose higher than themselves? We do not need talent.

>Maj Carter, before becoming a Special Operations Officer, was an Infantry Officer, serving as a Platoon Commander, Company Executive Officer, and Company Commander, with deployment experience as both. Before commissioning in the Marine Corps, he was a strength and conditioning coach, a researcher in sports science, and a graduate teaching assistant. He is still currently active in the strength and conditioning community with his research centric to holistic training approaches for human performance.

Notes

1. Gen David H. Berger, Talent Management 2030, (Washington, DC: 2021).

2. Ibid.

3. Geoff Colvin, Talent is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else (New York: Portfolio/ Penguin, 2018).

4. Talent Management 2030.

5. Talent is Overrated.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Malcolm Gladwell, Outliers: The Story of Success (New York: Back Bay Books, 2008).

11. Mike Eruzione with Neal E. Boudette, The Making of a Miracle: The Untold Story of the Captain of the 1980 Gold Medal-Winning U.S. Olympic Hockey Team (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2020).

12. Talent is Overrated.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Talent Management 2030.

16. Alexander A. Vandegrift, “Bended Knee Speech,” Marine Corps University, March 30, 2024, https://www.usmcu.edu/Research/Marine-Corps-History-Division/Frequently-Requested-Topics/Historical-Documents-Orders-and-Speeches/Bended-Knee-Speech.

17. Jeremy Carter, “A Critical and Devastating Gap in our Leadership Traits, Principles, Evaluations, Ethos, and Culture: The Problem with Solutions,” Marine Corps Gazette 108, No. 7 (2024).

18. Jim Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap and Others Don’t (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2001).

19. Talent Management 2030.

20. John Wooden and Steven Jamison, Wooden on Leadership (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005).

21. Ibid.

22. Good to Great.

23. Talent Management 2030.

24. Ibid.

25. Gen David H. Berger, Training and Education 2030, (Washington, DC: 2023).

26. Jeremy Carter, “Strategic Competition and Stand-in Forces: A Novel View for Tactical Units,” Marine Corps Gazette 108, No. 8 (2024).

27. Jeremy Carter and Thomas Ochoa, “The Relationship Between Enlisted and Officers- Part 1: The T-Shape Philosophy,” Marine Corps Gazette 107, No. 7 (2023).

28. Talent Management 2030.

29. Ibid.

30. Daniel Coyle, The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups (New York: Bantam Books, 2018).

31. Jeremy Carter, “Achieving the Culture We Pursue: The DEMAC Approach,” Marine Corps Gazette (Submitted).

32. Talent Management 2030.

33. Ibid.

34. “Achieving the Culture We Pursue.”

35. “A Critical and Devastating Gap in our Leadership Traits, Principles, Evaluations, Ethos, and Culture.”

36. “Achieving the Culture We Pursue.”

37. Ibid.

38. Talent Management 2030.

39. Douglas W. Hubbard, How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of “Intangibles” in Business, 3d edition (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014); “Achieving the Culture We Pursue;” and Headquarters Marine Corps: MCDP 1, Warfighting, (Washington, DC: 1997).

40. Jeremy Carter, “United States Marine Corps Commandos: Enabling Joint Forcible Entry,” Marine Corps Gazette 107, No. 7. (2023).

41. David Epstein, The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance (New York: Penguin Random House LLC, 2014).

42. Carol S. Dweck, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success- How We Can Learn to Fulfill Our Potential (New York: Ballantine Books, 2016).

43. Mindset.

44. The Making of a Miracle.

45. Talent Management 2030.

46. Ibid.

47. Ibid.