A Small Piece of Cloth: The History of the Marine Corps’ Shoulder Sleeve Insignia

By: GySgt Chase McGrorty-HunterPosted on October 15, 2024

“Each night during the northward trip I had noticed the beautiful Southern Cross constellation slipping lower and lower on the starlit horizon. Finally, it disappeared. It was the only thing about the South and Central Pacific I would miss. The Southern Cross formed a part of our 1st Marine Division shoulder patch and was, therefore, especially symbolic.

We had intense pride in the identification with our units and drew considerable strength from the symbolism attached to them. As we drew closer to Okinawa, the knowledge that I was a member of Company K, 3d Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division helped me prepare myself for what I knew was coming.”

—Eugene Sledge, “With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa”

This pride that Eugene Sledge described while en route to the bloody battle of Okinawa is a feeling that generations of Marines have found in their unit insignia. These symbols serve as beacons of motivation that act as a connecting thread from one generation of Marines to the next. Many of the logos that represent Marine Corps units today stem from two very distinct eras in the Corps’ history—times when Marines wore the insignia proudly affixed to their shoulders.

One of the most iconic images of Marines in World War II, outside of combat, is that of young Marines on liberty in their service uniforms with their unit patches on their sleeves. Although the use of shoulder sleeve insignia (SSI) was at its peak in this period, it was not the first time Marines represented the units they served with on their uniforms.

The history of the SSI predates the founding of the nation and likely finds its origins in the heraldry displayed by the knights, who would often paint their symbol onto their armor and shields. British officers adopted patches as a form to identify ranks many years later. In the United States, instances of SSI date back to the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, and, most prominently, the Civil War, when some states sewed insignia on their uniforms to distinguish separate outfits. However, because these patches were made by hand, they were often crude, never distributed in abundance, and impossible to standardize. Although SSI was used during these time frames, this is not the historical beginning that the modern-day military would recognize for the insignia as they are thought of today.

It was not until WW I, a war in which the character of fighting was dramatically transformed by the effects of the Industrial Revolution, that the SSI became the official tradition to the U.S. military that is known as today. Upon their deployment to France in 1918, the 81st Division of the U.S. Army became the first unit to adopt an insignia that would be worn. A black wildcat was authorized as their SSI by the General Headquarters American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), which “recognized the value of this means of building morale and helping troops to reassemble under their own officers after an offensive.” As a result, on Oct. 19, 1918, all units that fell under the AEF were tasked with submitting their own proposals for SSI.

For the Marines who fell under the command of the Army in this theater, developing a unit branding to be worn on their shoulders filled a different role as well. It would help further distinguish them from their Army counterparts. Because of the shortage of uniforms to supply the surge of troops sent over quickly to the western front, and to simplify supply and distribution procedures, General Pershing, Supreme Allied Commander, AEF, ordered all units to don the U.S. Army olive-drab uniform. Almost immediately Marines began looking for ways to differentiate themselves, and thus began the tradition of affixing the eagle, globe and anchor to their neck tabs and helmets.

Earlier in the year, the 2nd Division, an Army unit commanded by Marine Major General John A. Lejeune and housing all of the 5th and 6th Marine regiments as well as Army units, had hosted a competition for a logo which was to be painted on all vehicles to help with identification. The final logo was a combination of the first- and second-place entries, an Indian head and a white star, respectively. Because this logo had already been adopted by the division and was being used widely to mark gear, MajGen Lejeune submitted his response to the AEF headquarters in a memo dated Oct. 21, 1918, to establish this as the division’s SSI. Variations in background colors and shapes on the patches distinguished the 5th and 6th Marine Regiments as well as their supporting components.

This new SSI would be sewn onto the uniform sleeves of the Marines in France until they returned to Quantico in the summer of 1919. At home, they exchanged their Army uniforms for their own and transferred their patches over to signify their service in the Great War. Soon after their return to the States, all Marine units fell back under the Naval command, and the use of SSI insignia was discontinued. But the insignia’s design would have a life much longer still, representing the regiment and its subunits aboard Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, N.C., to this day.

The 5th Marine Brigade, stood up to assist these regiments in WW I, also had its own SSI approved by Headquarters Marine Corps before returning home from Europe: a crimson square with a black eagle, globe and anchor in the center and a gold “V” through its middle.

In the interwar years, the Army continued the use of SSI and expanded its use to other units under its command, but it was not until the start of World War II that Marines would again dawn the organizational emblems of the units they fought for.

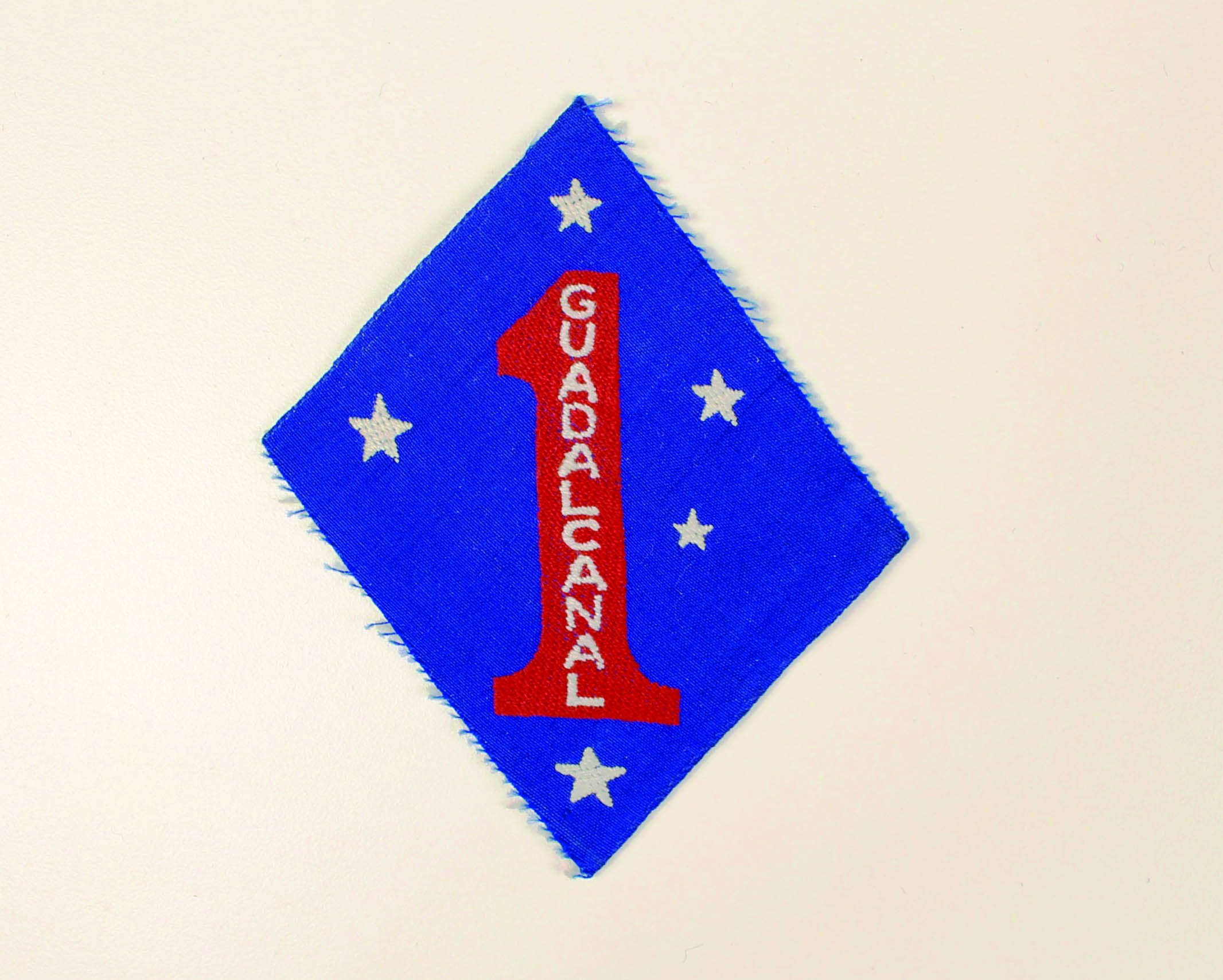

Many believe that the first official patch of WW II for the Marines was the 1stMarDiv’s famous blue diamond. Although this is the patch that started the general adoption for SSI by the Marine Corps, it was not the first time Marines were sewing SSI on their shoulders again. Even before America entered the war, the 1st Marine Brigade Provisional was activated for service in Iceland to serve alongside the British garrison to defend the land from any hostile attack.

The Marines were so well received by the British troops that, on top of being provided with gear and a place to live, they were honored by British Commander General Henry O. Curtis with the privilege of wearing the unit’s logo, a white polar bear, on service and dress uniforms. This request was authorized by Commandant of the Marine Corps Lieutenant General Thomas Holcomb under the condition that they be removed before returning stateside, thus making it a theater-only allowance.

Only a few months after the arrival of Marines in Iceland, the nation would be thrust into war, and the Marine Corps would shift its focus to becoming the primary fighting force in the Pacific theater. In August of 1942, Marines would have their chance to prove to the nation and the world the ability of a free nation to prevail on the battlefield against the tyrannical rule of an empire. And that test would come on the island of Guadalcanal. After four bloody months of combat, the 1stMarDiv had proven they could defeat their adversary in battle cementing themselves in the history of the nation. When the island was turned over to reinforcements in December 1942, the division’s commanding general, future Commandant Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift began his departure to Australia, where the division would reassemble for rest, liberty, and training for future battles. It was on this plane ride south that the blue diamond was birthed into Corps history. This story is best captured in “The Old Breed: A History of the First Marine Division in World War II” by George McMillan, and is as follows:

“They sat in facing bucket seats, between them the litter of packs, seabags, typewriters, briefcases—the kinds of things that staff officers would necessarily bring out of battle.

“General Vandegrift had begun to be a little bored with the monotony of the long plane ride. ‘Twining,’ he said, ‘what are you doing?’

“Twining, full colonel and division operations officer, handed Vandegrift a sketch. It was on overlay paper.

“ ‘An idea I had for a shoulder patch,’ said Twining. ‘The stars are the Southern Cross.’

“Vandegrift looked at it for a moment, scribbled something on it, and handed it back to Twining who saw the word, “Approved,” with the initials, “A.A.V.”

“That had been on the ride from Guadalcanal to Brisbane. Because the first few days in Australia were hectic, Twining did nothing else about the patch until one morning he was called to Vandegrift’s quarters.

“ ‘Well, Twining, where’s your patch?’ Vandegrift asked, to the discomfort of Twining.

“ ‘I bought a box of watercolors,’ ” Twining says in recalling the incident, ‘and turned in with malaria. I made six sketches, each with a different color scheme. In a couple of days, I went back to the General with my finished drawings. He studied them only a minute or so and then approved the one that is now the Division patch.

“Twining knew that there was more to his mission. He placed an order for a hundred thousand.’’

Not long afterwards, the Marine Corps officially authorized the wear of SSI fleetwide in the Letter of Instruction No. 372, dated March 1943. This letter designated that the senior officer in theater would be the approver of designs for units, that SSI would not be worn in advanced combat zones, and which units would be granted SSI. By the end of WW II, there would be 33 unique SSIs authorized for wear by Marines serving in the Fleet Marine Force.

During the war, there were some issues with fielding patches, most prominently with the 2ndMarDiv’s unit logo. Three variations of the patch exist as a result of this confusion. Those who replaced the 1stMarDiv for the final two months of fighting on Guadalcanal adopted the same blue diamond logo as the 1stMarDiv but had substituted the large number one in the center with a red coral snake in the shape of a number two. This logo was never officially approved but was worn for some time by Marines in the division.

The official 2ndMarDiv logo that persists to this day is the red spearhead with a white hand holding a golden torch with the number two. Surrounding the centerpiece are the stars of the Southern Cross, like the 1stMarDiv logo. But even in producing these official patches, there were still issues in communication between Marines and the companies making the patches. Most notably this resulted in a large quantity of patches going into circulation with the shape of an upside-down heart instead of a spearhead. This patch is affectionately referred to as the kidney patch by collectors nowadays.

The legendary logos that represent the fighting units of the force today were all created during the war: the 3rdMarDiv’s trinity, 4thMarDiv’s bold four, the aircraft wing’s gold wings and Roman numerals to delineate, and Edson’s Raiders’ modern-day Jolly Rodgers skull. And along with the Marines who bore these representations on their arms, their Navy corpsmen did so proudly as well.

Following the war, a memorandum was sent to the Commandant to determine whether SSI should be discontinued. Some of the reasons presented on both sides were that in the post-war Marine Corps, almost all of the units wearing SSI would be disbanded; wearing SSI is an Army tradition; unit pride, as well as prejudice, is fostered by wearing them; the Marine emblem is distinctive enough; and finally they may have some value for use in recruiting. Some of the conclusions drawn from these points were that “the use of SSI is a custom alien to the tradition of the Marine Corps,” that because the Marine Corps would shrink back down to a small force it would be unnecessary, and that pride in the Marine Corps should be prioritized over that in units. Ultimately it was recommended that they be discontinued, with the exception that recruiters could still wear theirs. Letter of Instruction No. 1499 officially ended the use of SSI, effective Jan. 1, 1948. In 1952, Marines pushed to bring SSI back, and the plea made its way to the uniform board in study No. 2-1952. The board ruled against the readoption, restating all the same reasons verbatim from memo 1499 four years prior.

As the Marine Corps pivots back to its amphibious roots in the Pacific much like the Marines of WW II, it is unknown if Marines will wear SSI on their uniforms again and carry on the tradition that gave rise to many of its most storied units. However, the logos themselves have been carried on and found a home in the units and with the Marines they represented. And although many of the units in existence during WW II were disbanded following the war, the insignia designed for all the Marine divisions, air wings and Marine Raiders are the same logos that represent those units today. Emblems born in the cauldron of fire that is combat and solidified for generations of Marines to come. For the decades following the war, and even now, it would be almost impossible to step foot on a Marine Corps base without seeing these historical logos represented all over the place. From stickers on cars to tattoos inked into Marines’ skin, the pride in unit history and lineage runs deeper than ever.

With the rise and proliferation of social media, not only unit pride but even SSI has found a new home among Marines. Even though SSI has not been officially worn for more than 80 years, the ability for Marines to gather online into communities has resulted in a common idea circulating the internet: a call to bring back tradition and reinstate the use of SSI. Tens of thousands of Marines active, reserve, and veteran—officer and enlisted, have joined in on this movement trending online. Following many of the most prominent leaders in the space today, this topic is often posted about and shared around spaces primarily in the Instagram “mil community.”

Since none of these Marines have lived long enough to experience this tradition—or in some cases even met someone who has—why there is such a strong desire to bring the SSI back? One thing is apparent, though, and that is that Marines believe that SSI is not a “custom alien to the tradition of the Marine Corps” and in fact is a custom that was built out of the very eras that defined what has become the Marine Corps.

Authors bio: GySgt Chase McGrorty-Hunter is a cyber network chief with 9th Communications Battalion. He is an avid writer and founder of the Bayonet Warfighting Society.