The Battle for Najaf, Part 2: Thunder Road

By: Kyle WattsPosted on August 15, 2024

On Aug. 7, 2004, the Marines and Mahdi Militia brawling over Najaf steeled themselves for the battle’s next phase. After two days of harrowing conflict in Najaf’s cemetery, the Marines realized how sorely outnumbered they were. Colonel Anthony Haslam, the 11th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) Commanding Officer, radioed for reinforcements to swiftly defeat the militia and their leader, Muqtada al-Sadr. The U.S. Army’s 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry and 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry rolled into Najaf on Aug. 8 with dozens of tanks, Bradley Fighting Vehicles and Armored Personnel Carriers.

Haslam retained overall command of the coalition force. He accelerated the original timetable for eradicating al-Sadr from his fortress inside the Imam Ali Shrine. Fire restrictions in the city slackened following the cemetery assault, but the shrine remained an untouchable exclusion zone. The militia exploited this fact, using the mosque as a de facto headquarters and staging ground, in violation of the international laws of armed conflict. Iraqi National Guard companies were the only force under Haslam’s command allowed to enter the holy site. Over the next few weeks, American forces would degrade the militia’s capacity to fight, while preparing the Iraqis for the final assault to kill or capture al-Sadr.

Haslam assigned the Army units to carry on the battle’s main effort in the cemetery. The following morning, tanks and Bradleys squeezed down the narrow dirt streets crisscrossing the mausoleums. Dismounted soldiers endured the fighting just as Marines had several days earlier. They slowly and methodically cleared tomb after tomb, tunnel after tunnel.

Marines, meanwhile, executed a series of raids targeting militia strongholds throughout the city. On Aug. 12, they returned to the site where the powder keg first ignited 10 days earlier; al-Sadr’s private residence. Lieutenant Colonel John Mayer, the commanding officer of Battalion Landing Team (BLT) 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, ordered a combined force of Marines and Iraqi National Guard to seize the complex, consisting of multiple houses, a hospital and a school.

Charlie Company, 1/4, forced their way through the hospital and into al-Sadr’s house. The cleric and his men bolted before the Marines arrived, offering no resistance. As the grunts cleared room after room, a firefight erupted across the complex at the school building, the targeted structure of the Iraqi National Guard. The Marines exited al-Sadr’s house and ran toward the gunfire.

Iraqi soldiers fled the militia’s onslaught. U.S. Army Captain Michael Tarlowski, the Special Forces commander over the Iraqi unit, charged into the building rallying his troops. He personally led the attack up a staircase, sprinting directly into a militia machine gun. Bullets tore through Tarlowski, killing him instantly. He tumbled down the stairs as Marines fought their way into the bottom floor.

The scene inside was a bloody, chaotic mess. More than a dozen Iraqis and two Americans lay wounded or dead. The insurgents on the second floor fortified their position at the top of the stairs. They fired out the windows at Marines on the street as they entered or exited the front door.

A grenade bounced down the stairs and detonated next to Lance Corporal Ryan Borgstrom. Shrapnel tore across his abdomen, knocking him back in a pool of his own blood. A corpsman patched the holes but could not stop the bleeding. He called for an immediate medevac.

A narrow street jutted out from the front of the school. Nearly 100 yards separated the building from an intersection where additional Marines took cover. The platoon pinned down inside the school had no option but to get Borgstrom to the intersection, where a stretcher team waited. Lucian Read, a photographer embedded with 1/4, captured the surreal moment when LCpl James Hassell wiped the sweat from his eyes, stepped forward, and told the others to put Borgstrom on his back.

Hassell’s decision came without hesitation but was not considered lightly. His platoon endured significant enemy fire bounding toward the school. Marines at the intersection remained under fire from the buildings lining the street. Insurgents waited at the windows above to cut down anyone leaving the building. Borgstrom’s body weight, plus full combat gear, totaled more than 200 pounds. Even so, Hassell heaved the wounded Marine up piggyback style. The 100-plus degree heat zapped his energy reserve. Adrenaline would have to push him through.

The platoon circled around Hassell and exploded out the front door. Grenades detonated and enemy bullets kicked up dirt around Hassell’s feet as he zig zagged toward the intersection. A Marine in a HMMWV recorded the heart-stopping sprint on video. Machine-gun fire erupts from somewhere off camera. Marines at the intersection take cover as sniper rounds strike nearby, then open fire down the street. Hassell finally emerges around the corner with Borgstrom bouncing on his back. He continues running past the stretcher bearers, who slow Hassell down and rush Borgstrom to a waiting medevac vehicle. The video failed to capture how Hassell, seemingly unfazed by his epic exertion, returned to his platoon to finish the fight in the school. Borgstrom reached the medical care he needed and survived.

Insurgents remained stubbornly lodged in the second floor inflicting additional Marine casualties. Mayer pulled everyone out of the building and ordered an airstrike. A U.S. Air Force jet leveled the school with a Maverick missile, burying the militia inside.

Despite aircraft from multiple services flying over Najaf, Marine Medium Helicopter squadron 166 (Reinforced) maintained a grueling flight schedule supporting the MEU’s daily raids and the Army’s push through the cemetery. At the beginning of the deployment, the squadron operated four AH-1W Cobras and three UH-1N Hueys, in addition to AV-8B Harriers, CH-46s and CH-53s. The loss of Captain Steve Mount and Capt Andrew Turner’s Huey on Aug. 5 placed additional strain on the remaining pilots. After getting shot down, Mount left the city to undergo surgery on his shattered right eye. Turner returned a few days later with both enlisted crew members who survived the crash, Staff Sergeant Patrick Burgess and Corporal Theodora Naranjo.

Turner, Burgess and Naranjo teamed up once more for their first mission back in action. Major Glen Butler joined as the Huey’s pilot in command. They lifted off heading toward the city. Capt Jason Grogan piloted his Cobra alongside them, with his copilot Vernice Armour, to accompany the mission. A two-Cobra flight ahead circled near a group of enemy occupied buildings. The four helicopters joined forces and stacked up in the sky to strafe enemy positions. Butler maneuvered the Huey down behind Grogan’s Cobra on an attack run.

“All I remember, I’d never seen it before, were these puffs of smoke in the air,” said Turner. “Probably a mix of antiaircraft fire and RPGs they had rigged to detonate in the air. It was pretty surreal. In the moment you’re not really thinking about it, but at some point you realize this is not good.”

Butler pulled out through the flak and climbed over the cemetery. On the radio, soldiers requested an airstrike on an enemy mortar hiding in a large mausoleum. Grogan lined up his Cobra on the target. He streaked in less than 100 feet off the deck, then popped up in the air. He nosed over, put the mortar in his sights and fired a TOW missile and 2.75-inch rockets.

Butler followed closely supporting Grogan’s attack run. He passed the controls to Turner, then dug in his pocket for a handheld digital camera he happened to bring on the flight. As Burgess and Naranjo blazed away firing both door guns behind him, he thrust the camera out the window and quickly snapped a photo. He didn’t have time to look through the viewfinder and frame the shot. Later that evening, Butler discovered the gem he had taken. The photo caught Grogan and Armour’s rockets impacting the target, with smoke trails still hanging in the air. The awesome photograph, of course, did not deter the other pilots in the ready room from giving Butler a hard time for taking “tourist photos” in the middle of a close air support mission.

Aircrews flew day and night. Every mission encountered a multitude of threats. On Butler’s first mission over Najaf, four RPGs targeted his chopper, and a seemingly endless stream of machine gun tracers.

“There was always a lot of gunfire, but one thing that was unique to the rest of my time in combat was the heavy weapons they had. We could see it, flying through flak bursts, and at the end of the battle the Marines found several antiaircraft artillery pieces. They also had several SA-7 man-portable air defense weapons.”

Helicopters routinely sustained battle damage. Grogan returned from one mission with a bullet in his seat armor. Another time, ground crews pulled rounds out of his Cobra’s fuel cell. In a third instance, an enemy bullet punched through the canopy next to Grogan’s head, ricocheted off the barrel of his rifle and slammed into his helmet. The round smashed his visor but exited the cockpit through the opposite side. Grogan was miraculously unscathed. Ground crewmen sutured the plexiglass canopy with wire. Grogan found another helmet and was back in the air shortly.

Support elements at Forward Operating Base Duke worked tirelessly to keep the aircraft flying. Beyond simple fixes like patching Grogan’s canopy, Marines performed complex maintenance in the open desert, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

“The ingenuity and bravery of everybody there, whether flying or on the ground, was really pretty amazing,” Butler reflected. “There was so much work going on behind the scenes that gets forgotten. We didn’t have a hangar, so these Marines were out there in this austere environment on the desert floor swapping Cobra engines at night, knowing that aircraft had to fly in the morning.”

Ordnance personnel worked equally hard to keep the aircraft loaded and ready for battle. MEU aircraft fired thousands upon thousands of machine gun rounds, rockets and missiles. Several days into the battle, the MEU ran so low on ammo that flight operations paused. CH-53E Super Stallions scattered to other Marine airfields and rushed back loads of ordnance. Tragically, one of these resupply choppers crashed in the desert on an overnight flight back to Najaf. Two Marines died and three were wounded.

Hospital Corpsman Matt Schmahl and the other Navy “docs” flying medevac missions in Najaf sustained an exhausting pace, even after the initial assault into the cemetery. The flying corpsmen needed help. At FOB Duke, they reached out to any corpsman available, looking for volunteers.

“We got around 10 volunteers to fly with us,” Schmahl remembered. “They were corpsmen assigned to supply units at the FOB. These people had no flight training, had maybe been in a helicopter, but never landed under fire. I give them tons of credit. They had no idea what they were getting into. They weren’t getting flight pay or anything else, they just wanted to get in the fight and help. As far as I know, our squadron commander told us that every patient who left that battle alive on one of our aircraft survived.”

This success rate could not have been accomplished without the tremendous effort and partnership of the corpsmen and Army medics serving on the ground.

“The guys on the ground did their very best to get patients packaged under fire, waiting on us to pick them up,” said Schmahl. “They were the ones, in my opinion, that saved their Marines. If they hadn’t prepared the patients the way they did, we would not have been able to get them to the hospital in time.”

Iraqi officials negotiated with Muqtada al-Sadr while the violence escalated. The Mahdi Milita refused to back down. On Aug. 15, U.S. Army Second Lieutenant James “Michael” Goins directed his tank down a narrow cemetery lane. As he sighted in the tank’s main gun on a target, an insurgent crept out from behind a mausoleum and scrambled on top the tank. He emptied an AK-47 magazine into the open tank commander’s hatch at point blank range killing Goins and his loader, Specialist Mark Zapata. The driver threw the tank in reverse as the enemy fighter leaped down and disappeared into the tombs. The tank veered off the slender pathway and backed into a two-story mausoleum. The structure collapsed, immobilizing the tank beneath a mound of concrete.

In the wake of the disaster, additional Marines and dismounted soldiers were tasked to provide security for tracked vehicles. Bravo Company’s 2nd Platoon returned to the cemetery on the night of Aug. 18-19 attached to the Army. After midnight, a mortar round landed on their position, wounding one Marine. Soldiers in a nearby Bradley spotted the enemy mortar tube and called for an air strike. Once again, the mission was denied due to the mortar’s proximity to the Imam Ali Shrine. Another round impacted, killing the Marines’ assault section leader Sergeant Harvey E. Parkerson III.

Al-Sadr’s militia paid dearly in blood that same night. Intelligence pinpointed an insurgent stronghold at a technical college on the west bank of the Euphrates River in the neighboring town of Kufa. Several hundred militia occupied the campus. The Marines planned a destruction raid that would bring the entire facility under a torrent of fire from the opposite bank. Anyone trying to flee would run directly into the teeth of more Marines lying in wait on the other side of the campus.

Two platoons from Company B, LAVs, mortars and a sniper team crossed the river around 2 a.m. More Marines secured escape routes out of the campus. Militia spotted the Marines across the river and opened fire. The raid force responded in kind. Huey and Cobra gunships tore through the night sky, unleashing their mini guns and rockets. A forward air controller brought in the crown jewel of firepower; a U.S. Air Force AC-130 gunship. The aircraft circled the campus spewing 25mm cannon and 105mm howitzer shells throughout the target area.

Fire and explosions inundated the college for the next hour. When it stopped, the night fell uncannily quiet. The militia were obliterated. The final butcher’s bill tallied 73 enemy killed and 102 wounded. Only one Marine sustained a minor wound.

Alpha Company executed another large-scale raid in Kufa two nights later, attacking a former police station commandeered by the militia. Tanks led the way, followed by Amphibious Assault Vehicles (AAVs) laden with infantry. The AC-130 gunship kept watch overhead. Intense fire greeted the Marines, with RPGs and 120mm mortars exploding and disabling one tank. Air support proved invaluable once again, destroying enemy fighters as they appeared. The AAVs opened up with .50-caliber machine guns and MK-19 automatic grenade launchers as the tail ramps dropped and Marines rushed out into the firefight. Company A secured the police station, adding more than 40 enemy to the battle’s body count and capturing 29.

Ten days of raiding, combined with the Army’s sweep through the cemetery, took a toll on the Mahdi Militia. Al-Sadr and his men retreated to the Imam Ali Shrine. A small square around the mosque’s immediate vicinity endured as the last hard line Americans could not cross. Even so, Iraqi officials were willing to risk a fight within the mosque itself to bring down al-Sadr. Four battalions of Iraqi soldiers trained for the final assault. Combined with the 11th MEU and Army units, a force nearly 6,000 strong prepared for the battle’s conclusion.

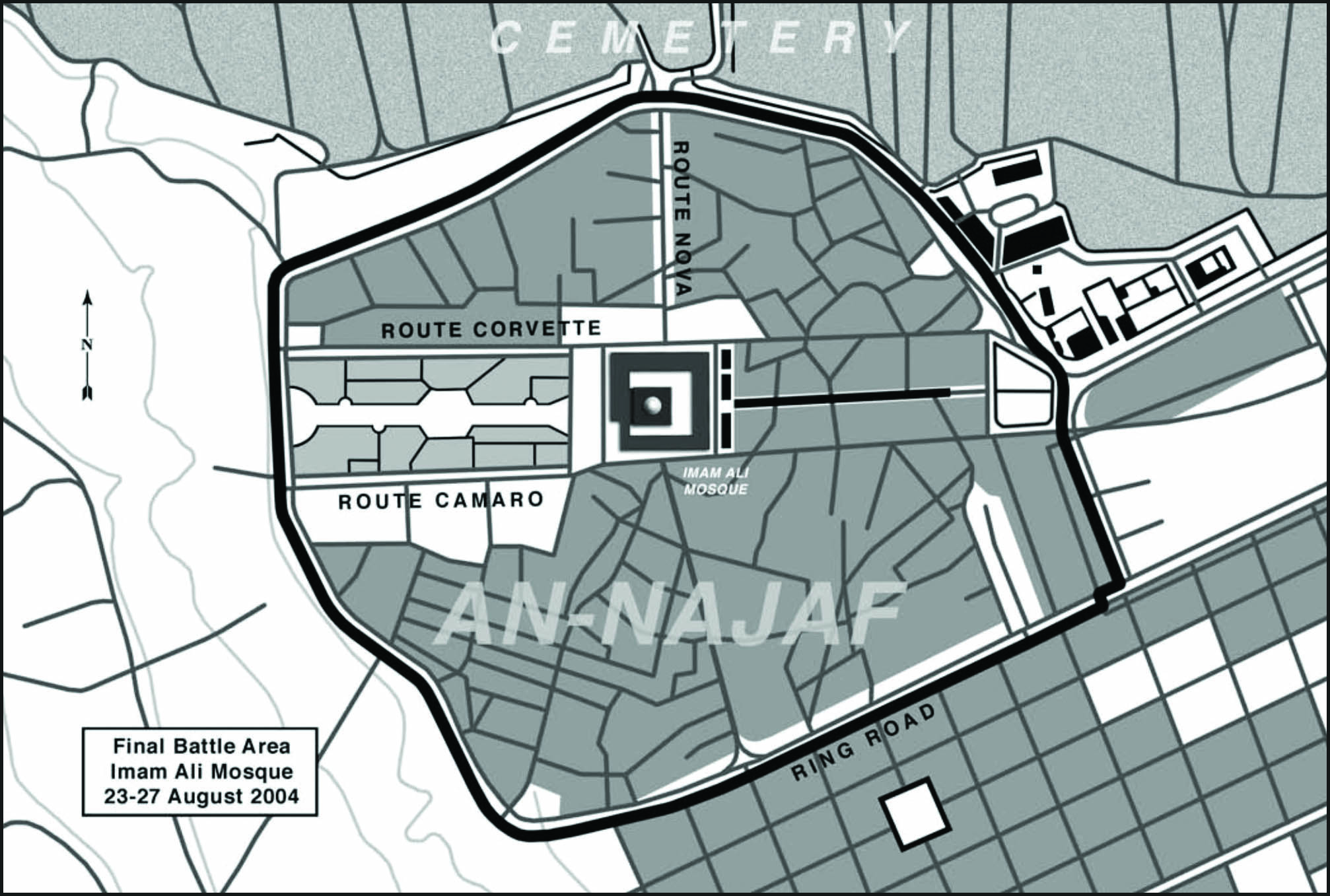

Planners of the final assault, dubbed “Thunder Road,” expected the worst was yet to come. Like an ancient fortress, the mosque lay at the very center of an urban web, encircled by “old city” Najaf.

“When you think ‘old’ being an American, you’re not thinking old like Iraqi old,” said Mayer. “The old city was just buildings upon buildings and buildings added to buildings. It was the craziest nonsensical place. The roads and alleyways didn’t flow like a modern city, more suited for goats than people. It was easy to punch holes in walls and move between structures without coming down to the street.”

Rising in stark contrast, a string of modern hotels and parking garages lined a pair of parallel roads along the western approach to the mosque. A street known as “Ring Road” ran around the circumference of the old city, separating the mosque and surrounding urban moat from the rest of Najaf.

By Aug. 21, commanders devised an assault plan. The main force would utilize the western approach through the modern hotels. Haslam ordered a probing raid that night along the intended route to gauge enemy resistance inside Ring Road. Led by the U.S. Army, an armored column set out at 1 a.m.

Enemy machine guns, RPGs and mortars engulfed the convoy as it crossed Ring Road. Attack helicopters and the AC-130 wiped out enemy positions on call. Details from the Army’s official history of the raid paint a terrifying picture. In just 30 minutes, the soldiers expended 68 tank main gun rounds, 1,200 rounds from the Bradleys’ 25mm chain guns, and 8 TOW missiles, along with an unknown number of rifle and machine-gun ammo. The tanks reached a suspected weapons cache inside a parking garage, fired a barrage of main gun rounds into the structure, then fought their way back to Ring Road.

The probing raid confirmed the ominous feelings. Even the terrifying conflict in the cemetery paled in comparison to fury experienced in the old city. Haslam and Mayer worked with Army leaders to solidify the battle plan. During a final “rehearsal of combat” drill on Aug. 22, senior leaders attended in person to weigh in, including Lieutenant General Thomas F. Metz, Commanding General of Multinational Forces Central Iraq, and LtGen James T. Conway, Commanding General of I Marine Expeditionary Force.

Three different attack forces would cross Ring Road and advance toward the mosque from the north, south and west. Mayer’s BLT would form the main assault force on the western approach. Mayer decided to insert his Marines into the hotels and garages near the outskirts and clear the structures leading up to the objective. Targets inside Ring Road were pre-approved for destruction to minimize delays in supporting fires, but the ultimate goal, entering the shrine to kill or capture al-Sadr, remained in limbo. The operation was set to commence the following night.

After dark on Aug. 23, Marine mortarmen dug in along a gun line in the desert west of Najaf and commenced the initial barrage of supporting fires. At FOB Hotel, the BLT artillery battery fired over 500 rounds into the old city, leveling preplanned targets and blanketing the area in shrapnel. They continued firing dangerously close even after the attack commenced.

Companies A and C loaded into AAVs as the primary assault force. A platoon of Bradleys reinforced 1stLt Russell Thomas’ tank platoon to lead the thrust beyond Ring Road. Like a scene out of World War II, when the Japanese emerged from tunnels following an intense bombardment, the Mahdi Militia met the armored column at Ring Road with determined ferocity.

“We were supposed to have around 15 minutes to secure the area before the grunts arrived,” said Thomas. “It sure didn’t feel like 15 minutes. Just imagine four Bradleys and four tanks constantly engaging. Constant main gun rounds, coaxial guns, 25 mm, TOW missiles; for me, it was the most intense part of the entire month.”

The grunts anticipating their part in the assault listened to the tanks’ progress on the battalion tactical channel. Squawk boxes broadcast the play-by-play, with Marines seated around listening, like it was a 1950s radio show. Thomas called out targets. The tank’s turbine engine whined in the background. The slow staccato of heavy machine-gun bursts drowned out his voice, intermixed with the faster rattle of the tank’s coaxial gun, and dramatically punctuated by explosions from the main gun. The Marines listening in could barely make out a word Thomas said. Nervous laughter mixed with awe as the Marines cheered on the tankers. Their turn came next.

Fifteen minutes was up. Thomas learned that AAVs were en route.

“I told them the area was still extremely hot and requested five or ten more minutes to lay down suppressive fire, but, the AAVs came up. They got under cover from one of the buildings there on the corner and dropped their tail ramps. That was a lot to ask of those Marines inside to get out under fire like that.”

Sergeant Landon Gant served as a Charlie Company machine gunner during the final assault.

“They turned off the AAVs while we were waiting and we could hear the explosions in the distance,” he recalled. “We were just like, ‘holy shit, they are getting it.’”

The AAV fired up. Gant triple checked his machine gun as they dashed toward the battle. The roar of gunfire grew louder than the engine’s whine inside the AAV. The smell of cordite penetrated the hull. A gunner in the turret above Gant opened fire. It wouldn’t be long now. The vehicle finally slowed and the tail ramp dropped.

Gant sprinted out the back. A hazy yellow glow from artillery illumination filtered down to the open street. Multi-story buildings towered above on either side of the road with muzzle flashes spuring from the windows. The AAVs stopped just meters away from the hotel entrance that was the objective. Despite their close proximity, four Marines sustained wounds from grenade shrapnel as they exited the vehicles. Gant followed after the others. A mortar round detonated close by. The shock blew him off his feet and knocked him unconscious. Less than a minute later, Gant came to, concussed and disoriented. He regained his footing and stumbled toward the hotel where Marines stacked up outside the front door.

“I remember one of my young machine gunners, a lance corporal, was in front of me as we were about to make entry. We looked across the street and there is an LAV just freaking hammering away, I mean nonstop, ‘POP POP POP POP POP!’ He looked back at me and yelled, ‘Sgt Gant, this is like a video game!’ I was just like, ‘Yeah, well this is f—king real dude! Now, GO!’ ”

“I felt like we were landing on the beach at Iwo Jima,” said Chris Schickling, the platoon commander of the Marines entering the hotel. “We didn’t initially know there was a basement. My first fire team went in and found the stairwell while I was trying to get the rest of the Marines inside.”

Gant entered the hotel with the first group of Marines. Every trace of light vanished, leaving the Marines in blackness. The stench of sulfur overwhelmed them. The terrific noise of the battle outside echoed off the concrete walls. Voices from insurgents on the upper floors streamed down an open stairwell. The Marines stumbled over rubble flung across the floor. As Gant searched through the dark, his prescription glasses fell off his face. He cursed aloud as he dropped to his knees and swept back and forth across the deck.

“By the grace of God, I found them,” Gant said. “All of this, of course, was happening while other actions were going on. It’s not like anyone stopped the assault just because Gant’s portholes popped off.”

He caught up with a squad as they proceeded down to the basement. He fumbled around in his pocket for his flashlight.

“We didn’t have a lot of the gear on our rifles back then that we have now. No one had light. The only reason I had a flashlight that night was because I bought it, and it wasn’t even attached to my weapon.”

Private First Class Ryan Cullenward led down the stairwell on point. He reached a landing and turned down the next flight of stairs. He collided face to face with an insurgent on the landing preparing to fire an RPG. Both men fell to the ground and dropped their weapons. Gant clicked on his flashlight.

Momentary spurts of light reached the landing as others moved in and out of the beam. Cullenward fell on the enemy soldier, punching him with bare hands. He drew his Ka-Bar fighting knife, then stabbed the insurgent to death. The man’s screams resounded up the staircase, the only indication for Marines on the first floor of the ultimate struggle happening below them.

“That insurgent Ryan killed was getting ready to fire his RPG into the room up the stairs and it would have killed all of us,” Schickling said. “He’s a hero.”

Cullenward rose in a state approaching shock and moved back up the stairs. Others pushed past him into the basement. A grenade exploded, striking four Marines with shrapnel. The wounded were dragged back up the stairs. Recon Marines on the first floor descended for a third attempt to take the basement. They threw two grenades before pushing down the last flight of stairs. Two insurgents hid in an opening under the stairs behind them with another RPG. The Recon Marines killed both before they could fire. They secured the rest of the basement, locating a cache of a dozen more rockets.

Marines advanced up the stairs to clear the remaining floors.

“Imagine an elevator shaft in the middle of the hotel with the ladder well wrapped around it going up,” Gant said. “At some point in time, these were probably pretty nice hotels, but we had blown them all to hell. We had a guy making his way back down the stairs from the upper floors and he fell down the elevator shaft. We just heard this bloodcurdling yell and were like, ‘what the f—k was that?’ I thought he got impaled or something. The only thing that saved him was his gear got hung on some exposed rebar, and other Marines were able to pull him out of the elevator shaft.”

Schickling’s platoon cleared the rest of the building, killing several more enemy fighters on the upper floors. Ten Marines were wounded taking the hotel. Company A fought into the old city on Company C’s left flank. By the end of the day on Aug. 24, the Marines secured the foothold needed to anchor the advance towards the mosque.

For the next two days, Marines and soldiers shrank the cordon. Marine, Navy SEAL, and Special Forces snipers flooded into the old city to combat the well-trained and accurate insurgent snipers hiding throughout the urban labyrinth. According to the USMC History Division publication on the battle, coalition snipers racked up 60 confirmed kills in a single 24-hour period. Militia snipers drew blood as well. Company A suffered its first KIAs of the battle when a sniper killed LCpl Alexander Arredondo on Aug. 25, and PFC Nick Skinner a day later.

Armored vehicles played a critical role in the fighting. During the day, tanks and Bradleys advanced down streets, drawing enemy out of their hiding spots for slaughter. At night, the same tactics were used to locate targets for the AC-130 circling above. Enemy fire remained so intense that lighter vehicles like AAVs offered inadequate protection from the volleys of RPGs being hurled at them. The Army loaned several M113 armored personnel carriers to the Marines for medevacs, enabling the corpsmen in side to roll in as close as possible to the casualties and extract them under fire.

During one daylight push, a call for help reached 1stLt Thomas inside his tank. Several Marine snipers were trapped inside a building by militia occupying the structure next door. The tanks were cleared to engage the enemy-held building with main gun rounds. Thomas moved down the tight street until the target came into view. The structure shared an adjoining wall with the building occupied by the snipers, like two townhomes in the middle of a row. The snipers waved a white sheet from a window, identifying their position. Sitting less than 20 feet away from the target building, point blank range for the tank, Thomas hesitated.

“I had to make sure they wanted me to fire. There’s a lot of over pressurization from the main gun and we thought it was a bad idea. They came back and authorized the shot, so I told them to stand by.”

Thomas fired a single round into the enemy building. A blinding dust cloud enveloped the tank.

“I couldn’t see what happened. Everyone in the tank was asking me what was going on, but I couldn’t see anything. I radioed the snipers and asked their situation. They came back and said they were still alive. A minute or two later, the dust settled. We looked up and the building the snipers were in was still there. The building we shot at, there was nothing left. The entire building just collapsed.”

Marine and Army units tied into each other’s flanks. By the afternoon of Aug. 26, the cordon locked in less than 100 meters from the mosque in any direction. Aircraft continued pummeling enemy occupied buildings. In one devastating strike, a jet streaked in over the mosque and dropped a 2,000-pound bomb in the city on the other side. Iraqi National Guard companies staged outside waiting for approval to assault the complex and finish off the militia. Instead, the Grand Ayatollah al-Sistani, the senior Shi’a cleric in Iraq, entered the mosque to negotiate. Shortly afterward, radios around the cordon delivered the order opposite of what they anticipated; cease fire. Facing complete destruction or surrender, Muqtada al-Sadr chose the latter. The battle for Najaf suddenly ended.

Marines around the mosque bit their tongues as surviving militia filtered out. According to the peace terms, al-Sadr and his men were free to lay down their arms and leave the city. The same insurgents who earlier that day were fighting and killing Americans in the streets now walked freely out to waiting vehicles. For the Marines who spent the previous 24 days sweating, bleeding and watching the Mahdi Militia maim or kill their brothers, the truce felt like a bitter disappointment. They wanted to finish the job.

Their feelings notwithstanding, the outcome of the battle proved successful. The Coalition Force won a tactical victory over the Mahdi Militia, despite turning the surviving faction loose to fight Americans again in Najaf, Fallujah and elsewhere. They delivered a political victory to the Iraqi government by ousting al-Sadr and restoring the government’s influence over the region, helping set the stage for the first free elections in the history of the country in January 2005. The city remained largely peaceful for the rest of the MEU’s time there. Marines assisted police in restoring order, helped rebuild schools and other buildings destroyed by the fighting, and dispersed almost $45 million in damage compensation to the civilian population of Najaf. Even so, the MEU executed numerous direct-action missions in the following weeks as die-hard militia sites were identified, detaining several high-value targets and sizable weapons caches.

The battle for Najaf took place in the first month of the 11th MEU’s deployment. Six months in country remained. The second battle of Fallujah loomed in the near future. Some Marines traveled north and took part in the urban fighting there. They brought with them their experience from Najaf.

“Almost immediately, the lessons we learned in Najaf played out in Fallujah,” said Mayer. “I think a lot of the tactics, techniques and procedures we used for fighting in an urban environment were transferred over and used during that battle.”

Just as quickly, the fighting in Fallujah ballooned into a wide scale, ferocious urban conflict that overshadowed the hard-fought victory in Najaf. Marines recommended for personal awards in Najaf were submitted through the same consideration process as those streaming out of Fallujah. Many wound up with downgraded medals. LCpl Justin Vaughn, who leaped under fire across the tops of mausoleums to retrieve his fallen squad leader in the cemetery, received a Navy Achievement Medal, as did LCpl James Hassell for his incredible sprint evacuating a wounded Marine carried on his back. PFC Ryan Cullenward was recommended for a Silver Star after his hand-to-hand fight during the final assault, which saved the lives of every Marine standing in the room above him. Cullenward received a Navy Commendation Medal. Sgt Yadir Reynoso was also recommended for the Silver Star posthumously for his courageous sacrifice covering the withdrawal of his squad in the cemetery. Reynoso’s award was initially downgraded to a Bronze Star, then later re-upgraded to the Silver Star.

Today, 20 years distant from the cemetery, the old city and the scorching Iraqi summer, veterans of Najaf recount their experiences in vivid detail with a mix of pride and sorrow. They suffered seven Marines killed and nearly 100 wounded in less than a month. Most are retired or left the Corps over the intervening years, but an impressive number remain on active duty. Landon Gant is now a commissioned engineer officer.

“As a drill instructor, a Company Commander, and throughout my career, I cared most about discipline,” Gant said. “Everything starts with individual discipline, and for me, that lesson was forged in Najaf. I remember walking by my company First Sergeant Justin LeHew, a Navy Cross recipient. He was taking every round out of his magazines and cleaning them individually, taking his magazines apart and cleaning the pieces, then putting everything back together and loading the magazines again, making sure those rounds would feed into his weapon when he needed them to. As a young NCO, when you see your first sergeant modeling that level of individual discipline, that leaves a lasting impact. Those are the small things that matter.”

Kevin Smith served with Charlie Company in Najaf as a radio operator. A teenage lance corporal in 2004, he retired last year as a chief warrant officer. Prescient words from Justin LeHew stuck with him just as powerfully for the last two decades.

“After the battle, I remember 1stSgt LeHew told all of us, ‘Don’t let this be the best thing you ever do in your life.’ At the time, I thought there is no way being here will be the best thing I ever do. But now, looking back, it’s like how can you beat that? I think a lot of us have struggled with that. It definitely made me look at my career differently. Late in my career, I was doing nothing but inspections. I had developed this mentality that if people weren’t dying and no one was in harm’s way, then it didn’t matter. I really had to convince myself to be the best staff officer that I could be.”

Muqtada al-Sadr is alive and politically active today in Iraq, a fact that still causes the Marines who fought him to grit their teeth. Most people, even veterans, know little of the things that transpired in Najaf in 2004. Despite the battle’s frustrating end, the Marines and soldiers accomplished something great, facing the staggering difficulties of a large urban conflict not seen since the Vietnam War. Many of the battle’s veterans thrived later in the Marines or in civilian life, using the lessons and experience from combat to propel them towards success. By any outsider’s standard, the part they played in the battle 20 years ago could never be the best thing they have ever done. For the warriors who fought there, though, the struggle over Najaf is, and will always remain, near the top of their list.

Author’s bio: Kyle Watts is the staff writer for Leatherneck. He served on active duty in the Marine Corps as a communications officer from 2009-2013. He is the 2019 winner of the Colonel Robert Debs Heinl Jr. Award for Marine Corps History. He lives in Richmond, Va., with his wife and three children.