The Golf Course

By: Tom SchuemanPosted on October 12, 2022

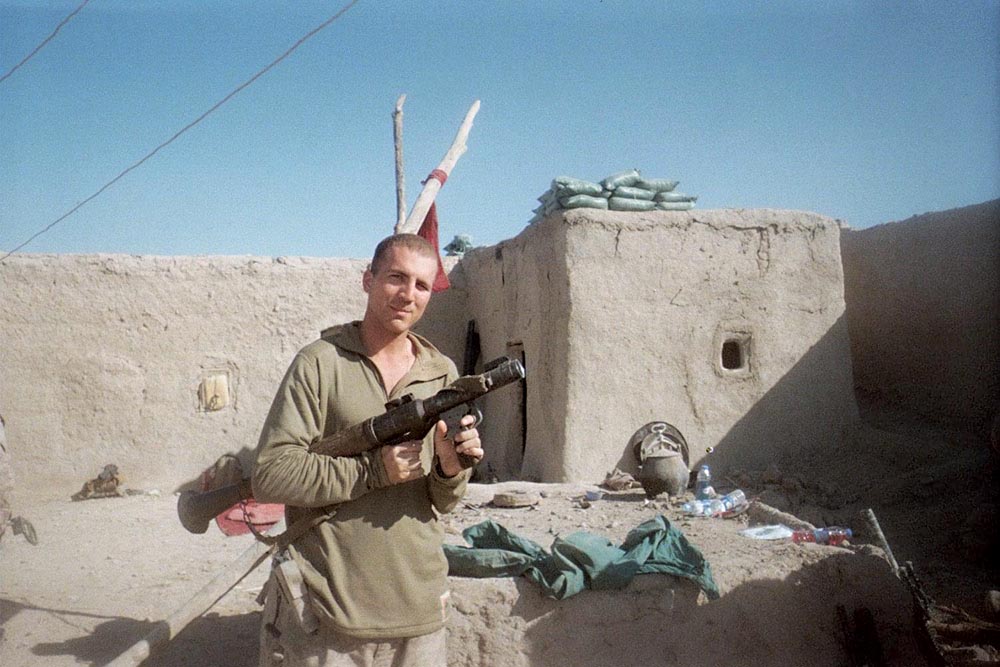

By Maj Tom Schueman, USMC And Zainullah Zaki

Editor’s note: This excerpt from the book “Always Faithful” by Maj Tom Schueman and his translator, Zainullah “Zak” Zaki, is told from Schueman’s perspective. It was reprinted with permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

We almost always started patrols out of Patrol Base (PB) Vegas by going through Kodezay since the Taliban were less likely to put an improvised explosive device (IED) there. They had long since learned they were better off not killing the village kids. I explained the facts of life in the moment to the lieutenant replacing me as we discussed the final familiarization patrol we would accompany them on. Most of 1st Platoon had already headed to Camp Leatherneck to begin the movement back to Camp Pendleton. But Sergeant Decker; Zainullah “Zak” Zaki; my machine-gun squad leader, Sergeant Nikirk; and I would serve as tour guides for a patrol otherwise composed of newly arrived Marines. The lieutenant leading the platoon replacing us was a brave, intelligent and talented officer. But I could tell that not everything I said was getting through.

“Ninety-eight percent of the world’s opium poppies grow in Afghanistan,” I told him. “Helmand Province, specifically Sangin district, is the heart of the drug market that funds the Taliban.”

He nodded. Training had already armed him with this fact. “Between September and December 2010, we were in a firefight on every patrol. Every. One. For 100 days.” Again, he nodded, face impassive.

I knew what he was thinking and feeling. I had been there seven months before, armed with training-based understanding rather than understanding born of experience. Every infantry officer who truly has the calling wants direct combat. After all, our stated mission is to locate, close with, and destroy the enemy. But the truth is that it’s all academic until combat is a present reality. Then you start thinking hard about the implications of everything you thought you wanted. You start feeling things that just can’t be fully understood until the possibility of violent death is truly manifest.

“Before January, we found hundreds of IEDs. But, man, look, back in January, the Taliban told the farmers they were behind on poppy production. The poppy farmers said they could not farm for fear of getting killed in the crossfire between us and the Taliban. So, the Taliban signed a fake-ass treaty, saying they were sick of fighting, and they just wanted to join the government. They said they would clean up the IEDs, turn in their weapons, and farm.”

I had the lieutenant’s attention. IEDs, and their effects, are the common thread of the global war on terror. A reduction in their use mean fewer potential casualties for his Marines. Zak interrupted us. Some children from Kodezay had arrived at PB Vegas to tell Zak that while we had been patrolling near the adjacent river the day before, the Taliban took advantage of our absence to spend a day digging in 15-20 IEDs all over the golf course. That was the perfect segue for me.

“So, the Taliban and the Afghan government signed the treaty. All of us here on the ground knew it was bullshit. The terms meant we stayed on our base for several days to allow these assholes to supposedly clear the IEDs that they had laid before without us shooting them. What they actually did was turn in three rusty antique rifles, like this treaty required, then used the time to reseed the area with two to three times what they laid previously. Then they told the farmers to get back out there and farm poppy to make them money to fight us with. So, when we went back out in January, there were no more firefights but way more IEDs. Which brings us to today.”

My replacement lifted his eyebrows and exhaled through pursed lips. IEDs are frankly terrifying. They are not what any of us signed up to fight. As long as a Marine has someone to shoot at, he is generally OK. Marines want to fight an enemy that wants to fight them. An IED kills without recourse beyond a medical evacuation and a hope that your legs are only gone below the knee. I could see his thoughts churning. Today was his patrol. In Marine lingo, he was in the left seat, the driver’s seat. I was in the right seat, as a passenger and tour guide to a pastoral paradise where poppies and IEDs were both planted in abundance. And he wanted to go through the golf course.

I shook my head and said, “We shouldn’t go through that field, man.” He looked at me and I saw the certainty the Corps trains in its leaders. “I don’t want to set a pattern of always going through the village,” he said.

“Dude, we always go through the village because the assholes don’t put IEDs in the village.”

“Not today. We’re going through the golf course.”

There was not much to do but say “OK” and get my guys ready for the patrol.

A Marine leader is expected to be where he or she can best control the unit and affect events at the point of friction. When accompanying one of my squads, I usually patrolled in the first third of the patrol, usually as the third or fourth man. The patrol was a bit larger than normal since we were augmenting the newly arrived platoon. Thus, there were five Marines across the golf course when Sergeant Nikirk stepped onto the field and disappeared in a cloud of smoke and mud, accompanied by a loud “POP!”

When you see one of your Marines injured or killed by an IED, it is an impotent feeling. Your enemy typically disappears long before they inflict actual damage upon you and your Marines. Unless they reveal themselves by firing at you, there is nothing to fight, but time as you try to stabilize a critically injured young man, convincing him to hold on through evacuation to the next level of care, and hope that you did not miss anything vital as you evaluated his injuries. I ran to Nikirk with Zak on my heels as always. There would be no need for him to interpret. He had simply become one of us over the months we spent together, and he was preparing to help me attempt to hold someone together as a Navy corpsman rendered lifesaving first aid.

But as the smoke cleared and the mud and dust settled from the air, I arrived at Nikirk’s side to see he was standing next to a partially ruptured, 40-pound jug of homemade explosive, much of it now dusted across his face. He was alive, perceptibly shaking from the experience of a low-order, partial detonation of ammonium nitrate homemade explosive (HME) intended to sympathetically detonate a 105 mm howitzer shell right under his feet. The combination should have left Nikirk a pink vapor drifting in the air with the lingering smell of ammonia. But because the area had recently experienced a lot of rain and Taliban quality control was low, the IED pushed him aside, plastered his face in the ammonium nitrate and aluminum used to make the explosive, and exposed the artillery shell that would have left him nothing but a memory. Since we had barely left friendly lines, and it had become clear that Nikirk was largely unharmed, I called for explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) to come out and destroy the IED. After an hour, they arrived and confirmed that the IED should have meant the end of more than one of us. They also noted that the IED was triggered by a tripwire, the first we had seen of such. Typically, IEDs in Sangin were triggered by the victim’s weight pushing down a pressure plate, which completed an ignition circuit.

Sgt Nikirk and Sgt Decker came to me and asked to return to base with EOD. I sent Nikirk back but told Decker he would have to remain. We needed his experience if things continued to go downhill. Sgt Decker looked at me, reminded me he had a son whom he had never met, and said, “This is bullshit, sir. These guys are going to get us killed.” Decker had never needed more than a direction and distance to and description of the thing I wanted attacked and destroyed. He was both courageous and cautious, a force of nature in combat. Now, for the first time in his life, Sgt Decker was ready to pack it in on a combat operation. I told Decker we were continuing on, then turned my attention to my incoming lieutenant counterpart and asked him his plan.

“We’re going to continue to push across the field.” Aggression aside, I was stunned.

“The only way we are going across that field,” I said, “is if you have the combat engineer back-clear from his position to us, then reclear it, since he had obviously missed at least one of the IEDs.”

Combat engineers accompanied us on most patrols and carried a metal-detecting sweeper intended to find IEDs and land mines. The incoming platoon commander gave the order.

We had been stationary for more than an hour as we dealt with Nikirk’s IED detonation, then EOD’s arrival and departure with Nikirk. That was way too long and now the Taliban certainly knew exactly where we were as the combat engineer began the exhaustive process of sweeping back across the flat, open expanse of the golf course from 500 meters away. He was halfway across the field, coming back to us, his sweeper ticking back and forth like a metronome, when the second IED blew. This time it was a complete detonation.

The combat engineer disappeared in the fire and mud and smoke. Before the debris had stopped falling, the Taliban unloaded on us with rifles, rocket-propelled grenades, and medium machine-gun fire. They knew someone had to go get the combat engineer. They knew there were more IEDs in the field. They wanted us moving around to hit them.

With the incoming fire everyone hit the deck. You could tell the difference between new guys and 3/5 Marines. The new guys were face-down in the dirt or neck-deep in an irrigation canal, rifles firing in no particular direction. Those of us on our last patrol were up on an arm, scanning for muzzle flashes and smoke. Painful experience told us we had to determine the source of the fire and put our own on them before they could hit one of us.

I was furious. This was our last patrol and after seven months, stupidity was going to kill us. I looked at Zak. All I could say was, “Son of a bitch! Can you believe this shit!?” He just shook his head in disbelief and said, “Lieutenant Tom, this is crazy.” Of course, Zak wasn’t leaving with us. He would stay here.

As I continued to scan for the enemy, out of the corner of my eye I saw Sgt Decker run onto the field toward the wounded combat engineer. The man who had asked me to let him return to PB Vegas, the one who reminded me he had never met the child he’d named Maximum Danger Decker, was running into the midst of an uncleared field planted with double digits’ worth of IEDs to retrieve a wounded Marine he didn’t know. I thought about the fact that it was our last patrol, that I had, only moments before, denied Decker a chance to return to safety, and that I now assumed I would soon be living with the fact that I denied a dead man a chance to meet his child.

I screamed, “DECKER!!!” He kept moving into the field. I screamed again, “SGT DECKER! STOP!” He looked back. I had no children.

“Come back here! You’re not going, I am!” I yelled.

Decker started moving back to me. I looked at Zak and asked, “Are you ready to go?”

Of course, he was. Zak’s eyes were open a bit wider than normal, but he was always ready to go. Even when, as was the case now, there was no reason for an interpreter. I just needed an extra set of hands to save an American life. I looked at the canal we had to cross. It was frothing from the bullets striking the water’s surface, as if a tropical rainstorm had set down in Sangin, but only on the golf course. I looked at the rest of the patrol, spread out in single file and hugging the earth, looking at nothing, just spraying bullets everywhere in a death blossom.

Zak and I were the only people up. We made convenient targets for the Taliban machine gunners as we ran up the column, me screaming, “WHERE IS THE CORPSMAN!?!?” The guy tasked with providing lifesaving care should have been up and moving already.

I saw a hand go up, inches above the dirt, his face pressed into the mud. I grabbed the drag strap on the back of his body armor, yelling, “Follow me!”

Time slowed down. I was moving forward, dragging the corpsman into the field toward the combat engineer, the extent of whose wounds I still did not know. Zak pushed him from behind as we all winced against the incoming hail of steel. I was thinking about what we needed to do. Simultaneously I thought, “My last f—ing day! My last f—ing day! Best-case scenario, I am not leaving Sangin with my legs. Worst-case scenario, I’m gonna be turned into pink mist by a 105 shell.”

There are often absurdity and seriousness in equal amount during combat. As we ran into the field, knowing that the first IED had been initiated by a tripwire, something we had never seen in Sangin, I was running like a football player doing high knee drills, trying to avoid additional tripwires. Every time my right foot struck the ground, I yelled, “Motherf—er!” like some absurdist running cadence.

For 250 meters it was, left foot, “Motherf—er!” left foot, “Motherf—er!” left foot, “Motherf—er!”

We reached the casualty, and I threw the corpsman at him so he could begin to do his job. Rain and the weight of the mud had again been our friend. The blast had thrown the combat engineer through the air, but the weight of the mud had tamped down the explosion. His major injury was an arm bone sticking out through his flesh, a relatively benign result.

I had been carrying an M32 grenade launcher for two months simply because I wanted to use it in a firefight. Imagine the world’s most powerful revolver as a six-shot, rotary-magazine, 40 mm weapon. Now I had my chance. It seemed like the thing to do since I still expected to die recrossing the field. As the corpsman worked on the wounded Marine, I started slinging grenades.

With 40 mm explosions not to their liking, Taliban fire slackened to an acceptable level. The corpsman pronounced the combat engineer ready to move and we headed back across the field without hitting any more of the IEDs we knew were there.

I got back to the incoming lieutenant and hissed, “This patrol is over!”

“I guess I should have maybe listened to you on the route.” No shit.

I was a good kid. Never drunk in high school, never in trouble. I’d never had a cigarette in my life. My grandmother died of emphysema. We got back to PB Vegas, and my first words were “Who has a cigarette?”

I stood and smoked my first cigarette, a Camel Blue, with Zak and it was so, so good. I never coughed once.

Authors’ bios:

Maj Tom Schueman served in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, as a platoon commander with 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines. He later redeployed to Afghanistan as a JTAC and advisor to the Afghan National Army while he was a member of the 1st Recon Bn. He later earned a master’s degree in literature. He is a graduate of Naval War College and is currently the ops officer with 3/5. He is the founder of the non-profit Patrol Base Abbate.

Zainullah “Zak” Zaki was raised by subsistence farmers in Afghanistan. He served as an interpreter for U.S. forces with the 3rd Bn, 5th Marines in Helmand Province beginning in 2010 and later worked for the U.S. government in Kunar Province. After more than six years battling bureaucracy, with Maj Schueman as his advocate, Zak successfully immigrated to America with his family in 2021.